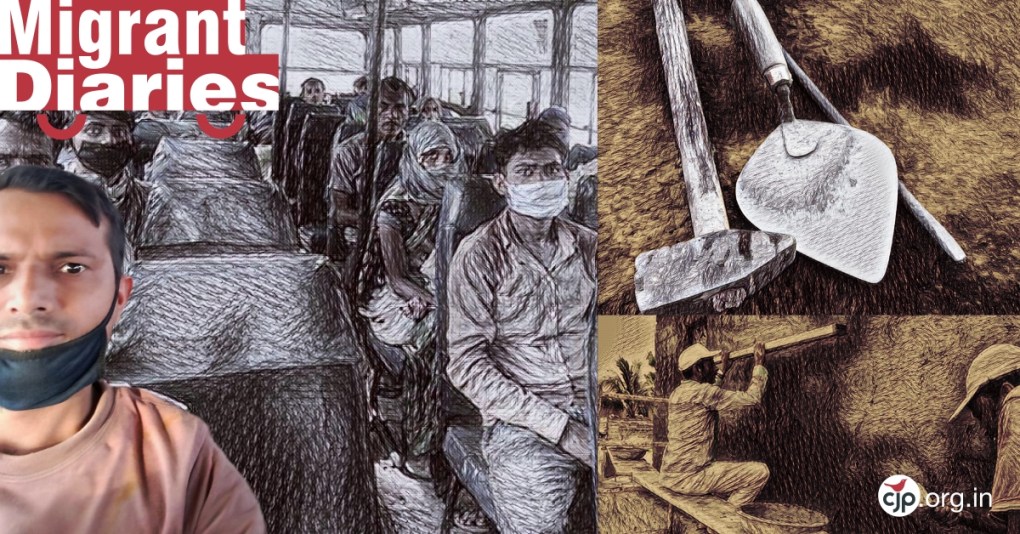

39-year-old Mohammed Jamaluddin is a skilled mason, who has been working in Mumbai for the past 13 years. But in wake of the coronavirus pandemic, he was forced to leave the city and undertake an arduous journey back home to his village in Birbhum, West Bengal. At first, he undertook two consequent journeys by bus, then travelled in the back of a truck, then a short distance even on foot, before again boarding a truck just so he could go home to his family!

Once he reached his village, he called to tell us, “The bus transport was provided by the government. But the journey was really painful and lack of proper coordination made it very challenging for homeward bound poor and helpless migrants.”

Jamaluddin, had never thought he would have to leave Mumbai this way. He had come to the city in 2007, and worked as a labourer for seven months. But he had to return to his village after that. “I returned to Mumbai in 2009, and since then I am working here. Initially used to work as a helper, but now I am a skilled mason. We are called ‘Naka Workers’, because every morning we stand at the naka (road crossings) and then the Mukadam, our contractor hires as many workers as he needs for the day. Everyone used to get work daily,” he recalls how he went about his work in Mumbai before the pandemic wreaked havoc on his life and livelihood.

Jamaluddin remembers the time when he would earn only Rs 110 when he worked as a helper. “As a skilled mason I earn Rs 1,000 each day, and get work 23-25 days a month on an average, so I earned between Rs 23,000-25000,” he says. Telling us about sharing accommodation with other migrant workers from West Bengal in Mumbai, Jamaluddin says, “There were more than 200 of us, seven of us shared a room, and we divided the Rs 5,000 rupees rent amongst ourselves.”

Jamaluddin had an annual work schedule and worked in Mumbai from October to June. As soon as the monsoon hit, work would slow down. He says, “During the rainy season I would always go back to my village and spend time with my wife, daughter who is three-years-old now, and my mother. I also have three brothers, but they live with their families.”

The visits home were spent relaxing and finishing any pending work in the house and sharing future plans with his wife. Jamaluddin says, “I would send Rs 15,000 back home and keep the rest. I have to save money because soon my daughter will start going to school, and I want to give her good quality education.”

When the lockdown was announced Jamaluddin did not panic. “All of us had some money so we brought ration for one month. But when the lockdown was extended, it was a real struggle for us. Our money was over and so was the ration. Then requested ration from various people but only Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) gave us rations that were enough for nearly a month,” he says. “While getting the food was a big relief, our real problem was that seven of us lived in one 100 sq ft room. A police post near our locality made it impossible for us to step out, but we managed to survive somehow,” he remembers the hot summer months almost trapped in the room.

He was keeping track of the news and heard that the trains were soon going to start. “I hoped we could return to our village but there was also news that the Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee had not given permissions for the train. We still filled up the emergency travel forms, but the police never called us. Living with six others in one small room during the scorching summer was really getting difficult. The whole day we were drenched in sweat, nights were a bit cooler but two of my roommates fell ill,” he recalls.

“By May 15, we began discussing if we should start walking to West Bengal, and hire whatever transport we find along the way. I was the only one suggesting that we wait for a few more days, as surely there will be some arrangements made. But everyone was frustrated and wanted to reach their village anyhow. That day, three of my roommates from Malda, West Bengal decided to go by truck, and paid Rs 3,500 per head,” says Jamaluddin.

On May 17 Jamaluddin’s other three roommates left paying Rs 4,000 per head for the journey back home. “Luckily, I heard about buses being arranged from Majiwada Thane to Chhattisgarh, so I went there and boarded the bus on May 18. I was so happy but my joy was short lived, as soon as I reached Madhya Pradesh, I saw that there was a waiting station for migrants from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh but there was nothing for West Bengal,” he says.

Jamaluddin made enquiries and was shocked at the response. “They asked why I came here, that it wasn’t the route to West Bengal,” says Jamaluddin recalling feeling shattered. But later he found that the police had made some arrangements and one bus left for Chhattisgarh from Madhya Pradesh. “We were 21 people, it took us two days to reach Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh. There we boarded trucks leaving for Kharagpur, West Bengal, there were a total of 35 people in the truck and we had paid 200 rupees per head,” he says recalling another arduous leg of the journey.

Jamaluddin reached Kharagpur on May 21 but was in for another shock. “There was a camp in Kharagpur from where officials were sending migrants to their villages, but an officer questioned us about where we came from, how did we come, did we have permission. I told him the route we took, by bus till Chhattisgarh and then via truck. However, he said they had not been informed about all this and told us to leave! ‘You go to Mumbai again or go anywhere but don’t wait here’ he said, it was raining at that time,” Jamaluddin recalls feeling crestfallen at this point.

A stunned Jamaluddin I tried to explain the tough journey he and his colleagues had just survived but the officer was not ready to listen. “He forced us to leave from there. So, twelve of us started walking on the highway, towards Birbhum,” still coming to terms with the heartless treatment they had been meted out by the police. But Jamaluddin’s luck was about to change. “We had only walked a few kilometres and met a man who appeared like god for us, who asked us where we were going. I told him the entire story,” he recalls that chance meeting with a good samaritan who took them to a petrol pump near the highway, owned by his friend. “He asked us to wait there for the night and told us that the next day, May 22 there will be trucks going from here to Birbhum and other places to collect and drop stones,” says Jamaluddin.

The man told Jamaluddin and his friends that he will arrange for them to travel on these trucks too. “We were happy, the kind man even arranged food for us so that night. We ate and slept at the petrol pump. The next morning, we grouped according to our districts, and three of us boarded the truck headed towards Birbhum,” says Jamaluddin. As feared, at the Birbhum check post the truck was stopped by the police, who asked to see permission papers, “We had none, our truck driver gave Rs 1,000 to the police officer and then we were allowed to go. We pooled in money and repaid our driver,” says Jamaluddin showcasing how bribery is often the only resort for helpless people. They reached Birbhum that night and were made to wait at the Panchayat School. “I wondered if things would have been better if I had gone with my roommates earlier,” says Jamaluddin.

On May 23, they were sent to the government hospital for screening, and subsequently quarantined for 12 days. But, according to Jamaluddin, that was yet another horrifying experience. “Conditions at the quarantine were very bad, we were not provided food by them, and asked our families to bring rations for us. We cooked food ourselves every day and ate, there was no responsibility shown by the local government,” he says recalling his ordeal.

“It was a very bad experience for me but I am grateful to have met many good people who helped us for food, water, biscuits along the way. In each state, there were people distributing supplies and helping migrants returning home, just like the man who helped us reach Birbhum. I also want to thank all of you at CJP, and everyone across our country who are helping the poor. I have no trust left in the government,” he says. “We are not at fault. This Covid-19 has come from other countries but it is the poor who have to suffer,” says Jamaluddin expressing anguish at how he feels that the authorities abandoned the poor in this crisis situation.

Meanwhile, economic compulsions have made Jamaluddin realise that he has no other option, but to return to Mumbai. “I am waiting for things to get normal so that I can again go back to Mumbai and work, because there is no work in my village, and even if there is a job the payment is so little,” he says.

Related:

Migrant Diaries: Hurdanand Behara