Due to the perfect and attractive handiwork skills of weaver artisans, the Baluchari silk saree in Bishnupur has been gaining fame across the country for many years. It’s also globally recognised. These Baluchari sarees are sold for Rs. 5,000 to Rs. 30,000 per piece. However, the weaver artisans do not receive proper wages. After making a saree, an artisan earns a measly Rs. 300!

Meanwhile, big owners and money laundering businesses exploit these artisans, whose living and working conditions are deteriorating. The cooperative societies have practically ceased functioning. So, where do they go and to whom do they tell about their painful livelihood conditions?

The state and Central governments seem to have little regard for minimum improvement in the living standards of these artisans. Also, there are no specific plans to uplift these artisans. As these artisans increasingly drown in severe crisis, struggling to get minimum nutritious food in accordance with their work effort, it remains to be seen how long Bengal’s Bishnupur Baluchari saree last?

History and Unique Identity of Baluchari Sarees

According to the history of Bengal’s garment industry, the Baluchari saree traces its origin in West Bengal. The name “Baluchari” came into existence from the weaving of muslin (silk) sarees in a small village called Baluchar in Murshidabad District of Bengal about 500 years ago.

In the 18th century, Murshidkuli Khan, the Nawab of Bengal, patronised its rich weaving tradition, bringing the craft of making this saree from Dhaka to Baluchar village and encouraging the handloom industry. Unfortunately, Baluchar village was submerged after a terrible flood of the Ganga River, forcing the muslin industry to move to Bishnupur in the Bankura District.

Several historical researchers have revealed in their studies that this silk saree was being made in Bishnupur long before that. According to the Malla dynasty, thousands of years ago, King Jagatmalla of Mallabhum patronised and encouraged the flourishing of the silk saree. This trend and tradition were maintained by successive Mallabhum kings, who allowed different kinds of crafts to flourish.

A major influence of Bishnupur terracotta temples can be seen in Baluchari sarees. Mythological and contemporary societal stories have been taken from the walls of terracotta temples to these silk sarees. Later, this trend declined, especially during British rule, due to political and financial reasons, causing it to become a dying craft. Most weaver artisans were compelled to give up the profession.

In the first half of the 20th century, famous artist Subho Tagore (full name Subhagendranath Tagore), a grandson of Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, felt the need to re-cultivate the rich tradition of Baluchari handicraft. He invited Akshay Kumar Das, a weaver artisan from Bishnupur, to his centre to learn jacquard weaving techniques. Das then went back to Bishnupur and worked hard to weave Baluchari on their looms with the financial and moral support from Hanuman Das Sarda, who was the local director of Bishnupur Silk Khadi Seva Mandal.

According to historian Manik Lal Singh, post-Independence, the government tried to revive this historical Baluchari saree. However, it did not go far; the price of raw materials, including silk and other ingredients, was always quite high. As a result, Baluchari sarees became more expensive than other sarees.

Additionally, in the post-Independence period, people’s financial conditions were not good. This caused the Baluchari market to remain downward. As a result, the artisans could not work more. Consequently, thousands of Baluchari weaver artisans suffered from financial distress. The whole Baluchari business was in the grip of four or five moneylenders in Bishnupur. They gave silk yarn to weavers to make cloth. One kilogramme of yarn used to make five sarees. Entire families of artisans were involved in this work.

“We used to get Rs 20 for working all day,” recalled Shyam Sundar Bit, 70, a Baluchari saree artisan in Bishnupur’s Vaishnabpara. He said in the 1970s, their condition became dire, with many artisans unable to fulfil their daily food needs.

How the Almost Dying Baluchari Saree was Revived

In 1977, after the Left Front government came to power, several cooperative societies were formed in Bishnupur to revive the Baluchari saree, as well as support weaver artisans. Artisans were enrolled in these coop societies and provided yarn to make Baluchari sarees. Additionally, looms were given to loomless weavers. Numerous daily wage artisans became owners. They submitted their production to the concerned cooperative societies and received proper remuneration.

Cooperatives also announced healthy competitions, awarding prizes, including television sets, to those who made more sarees. At the end of the year, weaver artisans received a part of the cooperative’s income as dividend.

Artisan Bharat Das, who stays in Vaishnabpara, told this reporter that he did not have a loom and made sarees for big owners for petty wages. When he received a loom from the cooperative, he got regular work, and was rewarded with a TV set for making sarees. Now, he owns three looms. Many such artisans in Bishnupur regained their existence with the help of cooperatives. The market for Baluchari sarees started growing rapidly.

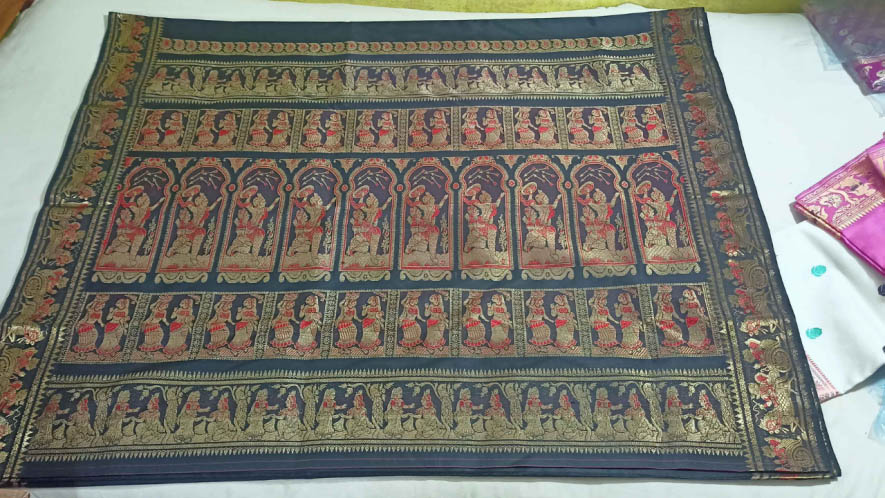

Baluchari sarees are famous for their unique craftsmanship and artistic value. These embroidered sarees are dominated by stories and characters from epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, giving them a royal look. Sarees depicting the story of Lord Krishna explaining the Bhagvad Gita to Arjun are among the most popular designs of Baluchari sarees. Especially the anchal craftsmanship of the saree fascinates people.

“The Left Front government made arrangements for Baluchari artisans to attend fairs in different parts of the country with their products. Government organisations like Manjushree, Tantushree, and Manjusha started buying sarees from cooperatives,” said Bamaprasad Rakshit, a Baluchari artisan in Bishnupur, adding that apart from the country, the value of this saree also increased in other countries.

In 2001, the Bankura District administration signed an agreement with the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) in Bishnupur to create a centre at Bishnupur K.G. Engineering College to bring modern designs to Baluchari sarees and make them in less time. Computerised designs were created, and many artisans got enrolled.

“Baluchari sarees became more attractive through this process,” said Professor Nihar Harza, who took over as the chairman of this new organisation. He said as a result, sarees were made by trained artisans in a short period of time, improving their financial status step by step.

How are Baluchari Artisans Spending Their Days Now?

“At present, most of the cooperatives are closed in Bishnupur. Only Bayon Silpi Cooperative Society is running with mere 50 artisans,” stated Bamaprasad Rakshit, an artisan and secretary of the Tant Sramik Union Bankura District Committee, affiliated with CITU.

He alleged that the present state government had no initiative to re-open the cooperatives. About 15,000 people are involved in Baluchari saree-making, but only 800 of them have their own loom. The rest work as daily wage labourers.

NIFT’s former chairman, Professor Nihar Hazra, alleged that after the Trinamool Congress-led government came to power in Bengal, the NIFT centre was closed. About 20 computers are damaged due to lying idle, and the rest of the centre’s items were destroyed. He said he had informed the sub-divisional administration several times, but no initiative had been taken to revive the state-of-the-art centre for the development of Baluchari sarees.

Haradhan Das and Shambhu Bit, Baluchari artisans from Vaishnabpara, said two artisans were needed to run the loom and make a saree. It takes three days to make one saree. The wage for one saree is Rs.1,800, which is divided between two artisans. Each artisan gets Rs. 300. They also claimed that they used to get silk yarn from cooperatives, which is very costly in the open market. When the cooperatives were active, they didn’t have to buy yarn in the market, allowing them to make Baluchari sarees at home as owners. The cooperatives would buy the sarees at a fair price. After the cooperatives closed down, the artisans reverted to being daily wage workers.

Baluchari saree artisan Haradhan Das makes sarees as a daily wage labourer at Vaishnabpara, Bishnupur.

Aasha Das, a resident of Vaishnabpara, said women of the house have to do the thread work. The silk thread is separated by soaking and drying it. They receive petty wages for this work. The dry thread is spun on a spinning wheel and cut into small pieces, which is locally called lolipakano.

Mihir Das, an artisan who does this work, said after working hard all day, they earn only Rs. 150. “We cannot arrange for even the minimum needed nutritious food and are suffering from chest, neck, and eye diseases,” he said.

Raju Pal, a leader of the Tant Sramik Union, told this reporter: “We have raised a demand from our organisation to give identity cards to all artisans, re-open the closed cooperatives, and set up a yarn bank here so that artisans can get yarn from the market at a lower price. Otherwise, these artisans cannot be saved.”

Bamaprasad Rakshit, another union leader, said these artisans have been making attractive, eye-catching sarees which are sold by traders in the market at high prices, while thousands of weavers are spending their days in hardship. This cannot continue.”

When asked, Prasenjit Ghose, Sub-divisional Officer (SDO) of Bishnupur, said NIFT would start working again. A six-month certificate course will be launched immediately to teach Baluchari saree work, he said, adding that an initiative is being taken to register the names of all artisans of Bishnupur.

All pictures taken by Madhu Sudan Chatterjee.

Courtesy: Newsclick