Thirty-Eight years after more than 4000 Sikhs were butchered in the streets of Delhi, we look back at our analyses that had recorded how justice was compromised, subverted and delayed. First published in the journal ‘Communalism Combat’ in 2009, republished by SabrangIndia in 2018.

Twenty-five years ago, in November 1984, as Delhi burned, no Sikh life in the capital was safe. Eminent writer Khushwant Singh sought shelter at the Swedish embassy. Justice SS Chadha of the Delhi high court had to move to the high court complex. His residence was no longer secure.

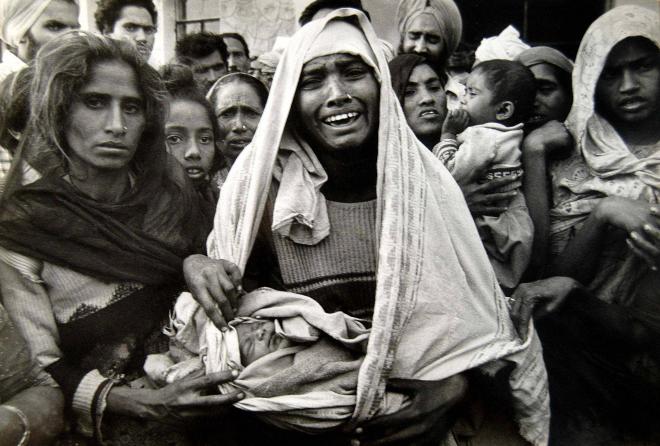

Image Courtesy: Sondeep Shankar

Though the official death toll in Delhi was 2,733, victims’ lawyers submitted a list to the officially appointed Ranganath Misra Commission in 1985 detailing the 3,870 Sikhs who had been killed. Twenty-six persons were arrested by the police on November 1 and 2, 1984; unbelievably however, all of them were Sikhs! So far only nine cases of murder related to the 1984 carnage have led to convictions. Only 20 persons have been convicted for murder in 25 years, a conviction rate of less than one per cent.

The cover-up

Within weeks of the massacre, a fact-finding report prepared by the civil liberties groups, People’s Union for Civil Liberties and People’s Union for Democratic Rights (‘Who are the Guilty’, PUCL-PUDR report, November 1984), named senior Congress leaders on the basis of allegations made by victims who had taken refuge in relief camps. However, no action against the perpetrators was forthcoming. The report listed HKL Bhagat, Jagdish Tytler, Sajjan Kumar and Lalit Maken among the Congress leaders active in inciting mobs against the Sikh community. The media had named only one, Dharam Das Shastri, a former MP.

Riding the wave of nationwide sympathy following Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the Congress party swept to power in the general elections held in late December. Her son, Rajiv, failed to isolate the leaders who had been specifically named for their role in the massacre. Far from being politically isolated, these men were instead given tickets for the polls by the party leadership. Worse, they contested and won the election.

Within a short and bloody spell of 48 to 72 hours, nearly 4,000 Sikhs, residents of Delhi, were massacred or burnt to death in cold blood. The central government announced no judicial steps for redressal, to identify and punish the guilty and offer justice to the victim survivors. Within weeks of the assassination and the massacre, the ruling party had switched to election mode and, winning a landslide victory in the polls, came to power with an overwhelming majority in the newly formed Lok Sabha. When Parliament met in January 1985, resolutions were passed condemning the assassination of the former prime minister; another condemned the loss of life in the Bhopal gas tragedy of December 1984. No official condolence motion was moved to mark the massacre of Sikhs. To date, the Indian Parliament has not rectified this shocking lapse.

None of the four politicians named for leading the mobs have so far been punished. Instead, their election to seats in Parliament, from the city where they were accused of leading mobs, signalled brute democratic sanction for the massacres. HKL Bhagat, who was named by several eyewitnesses as leading mobs, was chosen as the Congress party’s candidate from East Delhi, the worst affected area. Of the whopping 76.97 per cent of votes polled, Bhagat cornered a staggering 59.8 per cent (3,86,150 votes as opposed to the BJP’s 73,970). The majority of constituents chose to back a man identified as leading a murderous mob. Was this democratic sanction for carnage?

Similarly, Jagdish Tytler, chosen by the Congress party to contest elections from Sadar in Delhi, won with a whopping 62 per cent of the total 71.83 per cent of votes polled. His opponent, Madan Lal Khurana, won the remaining 35.78 per cent. Lalit Maken, another accused, fielded by the party from South Delhi, received 61.07 per cent of the 64.68 per cent of votes polled, capturing 2,15,898 votes.

Amidst the euphoria of the electoral victory that followed the massacre, these men were also elevated to more powerful positions in government. HKL Bhagat, previously a minister of state, was elevated to cabinet rank and Jagdish Tytler was made minister of state for the first time. Lalit Maken, formerly a councillor, had already been rewarded with a ticket for the polls in which he had won.

By early 1985 the Congress party was in the seat of power, with a 90 per cent majority in the Lok Sabha. Not surprisingly, the new government did not set up a commission of inquiry until forced to do so, five months after the massacre. It was under pressure to initiate talks with the more moderate Akalis (remember the Rajiv-Longowal accord) that Rajiv Gandhi, the new prime minister, was forced to accede to the precondition for talks set by the Sikh leadership – their demand that an inquiry commission be established to investigate the massacre. The Akalis had even threatened a nationwide agitation on April 13, 1985 to press their demand. Two days before the threatened stir, the Congress government finally announced the establishment of an inquiry commission.

A former judge of the Supreme Court, Justice Ranganath Misra, was appointed to head the commission set up in May 1985. But the commission did little to advance the cause of justice as the judge, who was subsequently associated with the Congress party’s human rights cell for several years, in fact covered up the role of the ruling Congress party in the violence, failing to summon top Congress leaders and subject them to the rigours of cross-examination. However, even the Misra Commission was compelled to concede that during the carnage the police refused to register any first information reports (FIRs) that named any policeman or person in authority as the accused:

“It is a fact and the commission on the basis of satisfaction records a finding that first information reports were not received if they implicated the police or any person in authority and the informants were required to delete such allegations from written reports. When oral reports were recorded, they were not taken down verbatim and brief statements dropping out allegations against police or other officials and men in power were written” (Misra Commission report).

The Jain-Banerjee Committee (one of three committees set up on the recommendation of the Misra Commission and which investigated omission in registration of cases) actually instructed the Delhi police in October 1987 to register a case of murder against Sajjan Kumar, who was a Congress MP from the Outer Delhi constituency in 1984, on the basis of an affidavit filed by a riot widow, Anwar Kaur. However, no action was taken until the cover-up was exposed by journalist Manoj Mitta in The Times of India. (An individual named Brahmanand Gupta, who was also named in the affidavit, obtained a stay order against the Jain-Banerjee Committee from the Delhi high court and the court allowed the matter to languish for two years, furthering injustice to the victims.)

The CBI finally registered a case against Sajjan Kumar only in 1990 and completed its investigations two years later. Apart from charging Sajjan Kumar with murder, the CBI also charged him with hate speech, invoking Section 153A of the Indian Penal Code. This required central government sanction before prosecution, which was obtained from the Narasimha Rao government only in June 1994.

In 1991 the Jain-Agarwal Committee, a panel set up to continue the unfinished task of the Jain-Banerjee Committee, had specifically recommended the registration of two cases against HKL Bhagat. The then lieutenant governor of Delhi, Markandey Singh, accepted the committee’s recommendation but Bhagat made a representation before him claiming that he had already been exonerated by the Misra Commission, a plea that was finally turned down on the grounds that the commission had not examined the matter beyond a prima facie look at the case. Despite the firm stand taken by the lieutenant governor, for five years no case was registered against Bhagat at all. It was only in 1996, when the Congress party was out of power, that the police registered the two cases in question.

The Jain-Agarwal Committee had in 1991 also recommended the registration of cases against other politicians and Markandey Singh had ordered the registration of those cases as well. But in a Machiavellian ploy, the Rao government actively prevented the registration of the stronger cases against politicians whilst registering those that relied on flimsier evidence thus ensuring that justice was not done. Manoj Mitta and HS Phoolka, co-authors of When a Tree Shook Delhi (Roli Books, 2007), exposed this as a government sham. They dug out, in affidavit form, the original testimonies of witnesses against all these politicians, demonstrating that the authorities, by replacing them with weak and false testimonies, had suppressed the honest, unambiguous and strong testimonies on oath.

Another panel appointed on the recommendation of the Misra Commission, the Kapur-Mittal Committee, which investigated acts of omission and commission by police officers, had identified delinquent police officials. A report submitted in 1990 by one of the two committee members, Kusum Lata Mittal, recommended various degrees of punishment for 72 police officials, including six IPS officers. But, on one flimsy pretext or another, the government has so far not taken any action against any of those indicted.

It was against this dismal background of legal deception and failure to punish the perpetrators that the Vajpayee government took the momentous decision in December 1999 to accept the demand for a fresh judicial inquiry into the 1984 carnage. In Parliament, the members of all political parties, including the Congress party, now under the leadership of Sonia Gandhi, passed a resolution supporting the government’s decision in this regard. The subsequent appointment of the Justice GT Nanavati Commission in May 2000, nearly 16 years after the killings, was an unprecedented development. The commission submitted its report in February 2005.

Through the findings of the Nanavati Commission, many eminent persons have for the first time been able to put on record how, during the massacre of 1984, the then union home minister, PV Narasimha Rao, and the then lieutenant governor of Delhi, PG Gavai, failed to take constitutionally binding and firm measures when urged to call in the army. Several depositions before the Nanavati Commission also provided fresh evidence against Congress leaders HKL Bhagat and Sajjan Kumar, reiterating their role in the violence. Analysis of the evidence before the commission also brought to light an important pattern/strategy followed by the police authorities during that period, which was to first disarm Sikhs and then arrest them. The Kusum Lata Mittal report, which revealed police complicity at the highest level, was also revealed for the first time through documents placed before the Nanavati Commission.

Communalism Combat has over the years revisited the 1984 carnage in its commitment as a journal to examine and illustrate the breakdown of the rule of law within a functioning, vibrant democracy. The 1984 Sikh massacre in the nation’s capital was also the first full-fledged anti-minority pogrom in independent India. That justice has not been done and perpetrators among policemen and politicians have not been brought to book is a comment on our agencies and institutions. We dedicate this issue to the pursuit of justice even as we pay homage to the victims and salute the grit and courage of the survivors.