The Koregaon celebration by Dalits questions the dominant and linear narrative of nation and nationalism.

The celebration of the Bhima Koregaon battle points to a re-emergence and celebration of Dalit militancy and a fundamental re-interpretation of history. Since the commemoration and celebration of Bhima Koregaon revolves around the defeat of Peshwas by the untouchable soldiers of the colonial army at that time, the fact that 21st century Dalits are commemorating it signals a powerful change in narrative. The battle was fought 200 years ago, and is regarded as a heroic chapter of Dalit historical memory.

The contradiction is rife and causes division in progressive history even today. While more fundamental ‘left progressive’ narratives have painted a linear narrative between the colonial powers and Indians, subaltern and depressed castes have pointed out, often that the fall-out of British colonalism –the English language, protestant and Scottish missionary schools etc—often enabled the utterly depressed classes and castes to empower and better themselves through education. This is a complex narrative that is often evaded by ‘progressive’ historians.

The Battle of Koregaon was fought on January 1, 1818, two hundred years ago, between the British East India Company and the Peshwa faction of the Maratha Confederacy, at Koregaon Bhima. The 28,000-strong Marathas, led by Peshwa Baji Rao II intended to attack Pune. On their way, they were met by an 800-strong Company force that was on its way to reinforce the British troops in Pune. The Peshwa dispatched around 2,000 soldiers to attack the Company force stationed in Koregaon. Led by Captain Francis Staunton, the Company troops defended their position for nearly 12 hours. The Marathas ultimately withdrew, fearing the arrival of a larger British force led by General Joseph Smith.

Acknowledging and remembering this battle – by turning up in such large numbers and assembling at the site – actually runs counter to the normative aspect of the caste system, which does not allow space to a Dalit to act as a militant. More significantly it calibrates the narrative of history since many of the oppressed castes actually found allies and breakthroughs with and within the actions of an otherwise brute colonial power.

Ancient Hindu scriptures like the Manusmriti have mentioned very clearly that a Dalit, or the lower caste Shudras and the Ati-Shudras, do not have the right to even have this force in their defence. By celebrating Koregaon in this manner, Dalits are saying: “We will celebrate the militancy that is part of our history”. Upper castes have either stifled our histories, or twisted them because they don’t find them suitable for continuing their narrative of Hindu nationalism.

Going to these sites has become a sort of alternate folk culture for both rural and urban Dalits. People are coming to Koregaon from states like Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka as well. Over the years, its hold on Dalit memory and consciousness has expanded.

With the spread of the internet, social media platforms and new Dalit web portals, there is a renewed effort to consolidate and reclaim Dalit histories and sites of resistance or memory. Now in India, we have also begun to observe Dalit History Month, which helps in this effort. The celebration at Koregaon is situated in this spectrum.

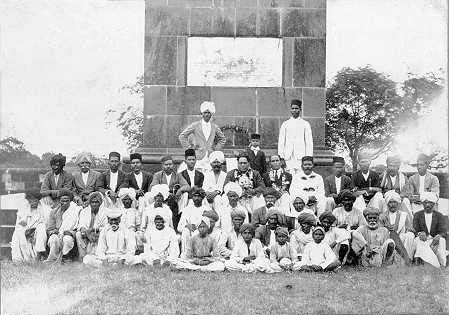

B.R. Ambedkar himself actively researched and visited such sites of Dalit history. He used to visit Bhima Koregaon every year, he even conducted a big conference there. Ambedkar continued the legacy of Dalit militancy when he formed the Samata Sainik Dal.

Ambedkar showed that militancy refers to a resolve to not be stopped, or threatened by any other force that is looking to subjugate you. And if the protection of the self is required, one is ready to do so by any method. He differentiated between the two meanings of the word ‘militancy’.

Now, this celebration is entering the realm of new spaces that Dalits are carving out in the new century. One can see this pattern in the emergence of small groups that are protesting against authorities, like the Bhim Army.

The Company troops of Indian origin included predominantly Mahar Dalit soldiers belonging to the Bombay Native Infantry, and therefore Dalit activists regard the battle as a heroic episode in Dalit history.

By the 1800s, the Marathas were organized into a loose confederacy, with the major constituents being the Peshwa of Pune, the Scindia of Gwalior, the Holkar of Indore, the Gaekwad of Baroda, and the Bhonsle of Nagpur. The British had subjugated and signed peace treaties with these factions,

establishing Residencies at their capitals. The British intervened in a revenue-sharing dispute between the Peshwa and Gaekwad, and on 13 June 1817, the Company forced Peshwa Baji Rao II to sign an agreement renouncing claims on Gaekwad’s reveues and ceding large swaths of territory to the British. This treaty of Pune formally ended the Peshwa’s titular overlordship over other Maratha chiefs, thus officially ending the Maratha confederacy. Soon after this, the Peshwa burnt down the British Residency at Pune, but was defeated in the Battle of Khadki near Pune on 5 November 1817.