Bengaluru, Mumbai & Kolkata: There was no–and never has been–electricity in the thatched-roof home that Rukhsana (name changed) shares with her parents. A small light flickered in the dark at the end of a row of paddy fields at the 16-year-old’s home in Basanti town in South 24 Parganas, West Bengal’s largest district and one of the “source districts for human and child trafficking” in India.

Rukhsana was sexually attacked thrice in four days by a man who had coaxed her into eloping. Yet, she is relatively lucky because she managed to escape, unlike thousands of girls abducted and forced into a life of sexual slavery, for whom there is no way back.

Rukhsana thought she was in love with the man she had met outside school. “During my conversations with him, he told me that he loved me and that his mother had passed away,” Rukhsana told IndiaSpend. It was only later, after she had escaped and found support from anti-trafficking counselors, that she realised that this man was probably a trafficker. She had not known of the concept before.

Like Rukhsana, thousands of girls in West Bengal are lured or forced into trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation (CSE).

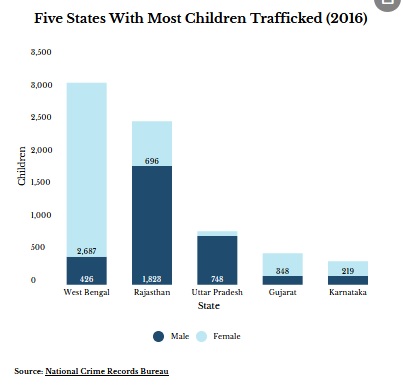

In 2016, the year for which the latest data are available, West Bengal reported the most children trafficked–3,113 or 34% of all–according to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. Of these, 86% or 2,687, were girls.

The state also reports more human trafficking than any other in India: the highest number of persons trafficked (4,164 or 28%), the most cases reported (3,579 or 44%) and the highest crime rate (3.81 human trafficking cases reported per 100,000 population).

“Trafficking for CSE was reported to happen in the context of girls eloping with boyfriends who then sold them into trafficking, or girls falling prey to fake marriage proposals and fake job offers,” according to a 2018 report from World Vision India, a charity.

Other reasons that led to trafficking were poverty–parents had no choice but to accept disguised job offers for their daughters–and kidnapping, the report titled Combat Child Trafficking For Sexual Exploitation In West Bengal said.

‘I ran away… as he went to buy a ticket’

In August 2018, Rukhsana travelled with the man in a “night coach”–that is, a sleeper bus. “Initially, he was well-behaved, but after the incident, I felt that he was bad,” she said.

“He laughed when I asked him to take me back home,” she said. “Although I thought of running away and coming back home, I never got a chance initially because he was always around.”

Eventually, she got suspicious when she heard him speak in Hindi, a language she does not understand, and say “Delhi”.

“I ran away when he made me wait as he went to buy a ticket, which I think was to Delhi,” said Rukhsana.

After travelling four-to-five hours by train, from a station whose name she does not remember, Rukhsana reached Sealdah station, about 70 km from Basanti. She had the Rs 100 she had taken when she had left home; she used it to get back home.

Although she is scared that the trafficker may come back, Rukhsana is among the few who were able to return home. He has not been traced yet.

“I will tell other girls not to go ahead if they see strangers trying to befriend them,” Rukhsana said.

Low awareness

About 59% adolescents did not know of any way to protect themselves from trafficking, and 72% did not know about services that could help them, the World Vision India study found.

It examined issues related to child trafficking for CSE in three districts of West Bengal–Kolkata, Darjeeling and 24 South Parganas. West Bengal is a focus area as three of the state’s districts–North 24 Parganas, South 24 Parganas and Murshidabad–lie along the porous international border with Bangladesh and are prone to trafficking. The state also shares borders with Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand, Sikkim and Assam, along with Nepal and Bhutan, making trafficking easy.

The study surveyed 136 women trafficked for CSE in the destination areas, 885 adolescents (aged 12-17 years) in the source areas, and 1,180 caregivers–people who spent the most time looking after the children, such as the biological mother, aunt, grandmother or father.

In addition, qualitative studies were conducted which included 12 focus group discussions with 211 participants, 13 key informant interviews–with police personnel, NGO workers and government officers involved in anti-child trafficking work–and 10 in-depth interviews with women in CSE. The surveys and interviews were conducted in February 2018.

As many as 52% caregivers and 45% adolescents in the source areas said they were aware of trafficking, while 14% of caregivers said they knew of trafficking incidents in their area in the preceding 12 months.

In the destination areas, 26% women in CSE who were surveyed said they had started as minors; 44% between 18 and 25 years, and 29% at 25 years and above. The median age for first sexual experience was 15 years; 43% of women said it was forced. Nearly half the women in CSE had encountered sexual violence prior to getting into it, the report said.

Anti-trafficking units resource-starved

Anti-human trafficking units are currently under-resourced and need more funding, said Michelle Mendonca, a Mumbai-based advocate.

Mendonca has been handling child- and sex-trafficking cases for 14 years now, and has trained judges and prosecutors on these issues.

“The police lack resources to conduct an in-depth investigation if the child is trafficked from a different state,” Mendonca said, adding that the police need to be held accountable once they are trained in dealing with cases of trafficking. They also need more resources.

Citizens can help by volunteering to be witnesses on sex trafficking rescues, and then providing evidence in court, said Mendonca.

Poverty and desperation lead people to unsafe migration, making them vulnerable to trafficking.

“But another important factor which enables trafficking is the culture of impunity,” said Mendonca. “The same recruiter can repeatedly traffic many vulnerable children from a village because arrests are generally focused on the place of exploitation and not on perpetrators complicit in other stages of trafficking.”

Young children are totally in the clutches of traffickers, Flavia Agnes, women’s rights lawyer and co-founder of Majlis, a non-profit that provides legal services to women and children, told IndiaSpend. “Delay in court is also a factor that has [an] adverse impact,” she said.

Rehabilitation often involves returning the child to the same parents who had initially trafficked them.

“We have to stop thinking that the natal family is a safe haven for young children and evolve innovative strategies of rehabilitation,” said Agnes. “The state has to take the onus to stop child trafficking in the country.”

Trafficking widespread across India

Three in five–or 9,034 of 15,379–persons trafficked in 2016 were children (below 18 years), NCRB data show. Of these, 4,911 (54%) were girls and 4,123 (46%) were boys.

West Bengal reported the most children trafficked, followed by Rajasthan (2,519), Uttar Pradesh (822) and Gujarat (485).

West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Odisha are common source areas for trafficking to red-light areas across India, according to the India Country Assessment Report 2013 on anti-human trafficking, brought out by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Sexual exploitation for prostitution (22%) was the second major purpose for human trafficking in 2016 in India, after forced labour (45%), NCRB data based on the statement of rescued victims and the accused showed.

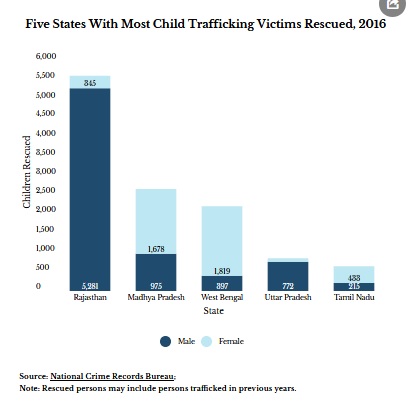

More than 23,000 victims were rescued in 2016, of which 61% or 14,183 were children and 39% adults. Of the 14,183 children, 61% were boys and 39% girls.

Rajasthan reported having rescued the most–5,626 or 40% of all victims below 18 years. Madhya Pradesh (2,653) was next, followed by West Bengal (2,216), Uttar Pradesh (852) and Tamil Nadu (648).

West Bengal rescued the most (1,819) female victims below 18 years, followed by Madhya Pradesh (1,678) and Tamil Nadu (433).

Gap in data and under-reporting

“Existing prevalence data–from secondary sources–for human trafficking for CSE do not exist as victims are a hidden population and there is no valid survey method to track it,” the World Vision report said. Estimates of women and girls in CSE vary from 70,000 to 3 million in India, it added.

NCRB data reveal only reported cases, Joseph Wesley, head of anti-child trafficking programme at World Vision India, told IndiaSpend. “From our experience, I can say that not all cases are reported, simply because parents are very hesitant to report or parents themselves are involved.”

“Police should be proactive in booking the cases under trafficking provisions,” he said. “Often cases are booked as kidnapping or missing person cases even though there is clear evidence of trafficking.”

Insufficient data hinder work for organisations such as World Vision India. Government agencies’ work also suffers–lack of data makes it difficult to detect and target high-prevalence areas, making it difficult to focus prevention and law enforcement efforts effectively, Wesley added.

“Lack of data makes it very difficult to track the gravity of the situation and the scanty numbers indicate that there is no immediate problem,” said Agnes. “Officials tend to dismiss or undermine the problem. Having accurate data on such a serious issue is critical to evolve effective strategies. Many NGOs are now in the process of compiling data about child trafficking. Though this is not official data, it is useful as a pointer.”

“There is a global data gap in reporting trafficking,” said Mendonca. “It is not easy for trafficking victims to report because many of them are from some of the most vulnerable and marginalised sections of society but a lot of data is lost due to lack of an integrated data collection system.”

“Integrated reporting and use of digital databases by police would result in more accurate national collation of data,” said Mendonca. “Once first information reports and chargesheets are entered into a digital system, there would be more accurate reports of trafficking crimes.”

(This article is a part of the World Vision India-LDV fellowship on child trafficking.)

Correction: The story was updated to correct the headline.

(Paliath is an analyst and Mallapur is a senior analyst at IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend