Members of All India Students Association (AISA) shout slogans as they hold placards during a protest outside police headquarters in New Delhi, India, October 18, 2015.

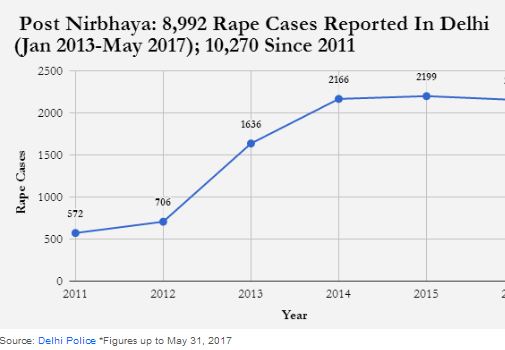

The number of rapes reported each year in Delhi has more than tripled over the last five years, registering an increase of 277% from 572 in 2011 to 2,155 in 2016, according to data released recently by the Delhi Police.

The year after the Nirbhaya incident—in which a 23-year-old paramedical student was raped by a group of men in a moving bus in Delhi on December 16, 2012—saw a 132% spike in the number of cases reported, with a sustained 32% increase thereafter, from 1,636 cases in 2013 to 2,155 in 2016.

Cases pertaining to “assault on a woman with intent to outrage her modesty” (under Section 354 of the Indian Penal Code) have increased by 473% from 727 in 2012 to 4,165 in 2016.

Government initiatives to ensure the safety of women–such as this National Vehicle Security and Tracking System and setting up of women’s helplines—have failed to effect a measurable drop in the number of reports of rape and other sex-related crimes.

At the same time, funds allocated for improving safety of women in public transport have been underutilised for years on end, as this ministerial reply in the Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament) indicates.

Continuing horror

The first five months of 2017 saw 836 rape cases being reported to the police.

The figure does not quite capture the continuing horror that women in the National Capital Region (NCR) face. In the 48 hours from June 19, 2017, for instance, five rape incidents were recorded. In addition to these, a 24-year-old woman was raped in a car parked outside a mall in Delhi on June 20, 2017, and another in which a 26-year-old woman was gangraped in a moving car on the outskirts of Delhi.

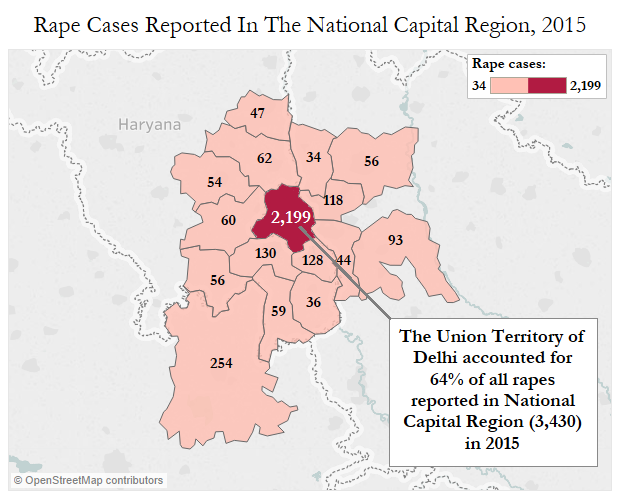

In 2015, the latest year for which National Crime Records Bureau data are available, the NCR region reported 3,430 rape cases, of which the Union Territory (UT) of Delhi alone reported 64%.

Source: National Crimes Record Bureau

The other most commonly reported crimes against women in Delhi are cruelty by the husband and the in-laws, kidnapping, and “insult to the modesty of women”.

Crimes covered under “assault on woman with intent to outrage her modesty” include relatively more serious crimes such as ‘sexual harassment’, ‘assault or use of criminal force to women with intent to disrobe,’ ‘voyeurism’ and ‘stalking.’

“Insult to modesty of women” covers sexually-motivated comments or gestures in a place of work, on public transport, and so on.

Why reporting of incidents has increased

The number of rapes reported each year in Delhi, as we said, rose 277% from 572 in 2011 to 2,155 in 2016, according to Delhi Police data.

The rise in the number of cases does not necessarily imply an increase in the number of rapes; it can mean greater willingness on the part of survivors to approach the authorities, as well as a greater propensity among police officials to register complaints.

One government official, speaking on condition of anonymity, told IndiaSpend that the rise in the number of reported rapes is due to advisories issued by the government and the Supreme Court of India that action would be taken against police personnel who fail to register a First Information Report (FIR) for rape and other cognisable offences.

Anant Kumar Asthana, a Delhi-based activist and lawyer, agreed: “Reporting of sexual offenses against women has gone up with stricter implementation of laws like Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012, and the [enactment of the] Criminal Law Amendment Act 2013.”

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012, obligates citizens to lodge complaints of sexual offences against children.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act, popularly known as the Nirbhaya Act, came into force on April 2, 2013, and inserted a provision in the Code of Criminal Procedure to make it mandatory for criminal complaints of a sexual nature to be recorded by women police officers, and prescribes rigorous imprisonment of between six months and two years in addition to a monetary penalty for a public servant who fails to register a complaint of a cognisable offence.

“With more stringent laws being passed, public awareness being created, and the media reporting more cases of sexual assault, reporting of cases has increased, but this is still far from being representative of the number of cases that occur,” Preethi Pinto, Program Coordinator on Violence against Women and Children at Mumbai-based SNEHA (Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action) told IndiaSpend.

Only 50% of all crimes are reported, and only half of these are registered as FIRs, a 2015 public survey entitled ‘Crime Victimisation and Safety Perception’ conducted by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) among households in Delhi and Mumbai, found.

CHRI estimated that one in 13 cases of sexual harassment were reported in Delhi.

At the same time, a comparison of Delhi Police reports from 2014 and 2015 reveals a rising trend in the number of rape cases withdrawn, from 81 to 104, possibly indicating a lack of faith in the criminal-justice system, especially as cases fail judicial scrutiny, IndiaSpend reported on August 12, 2016.

Conviction rate remains low

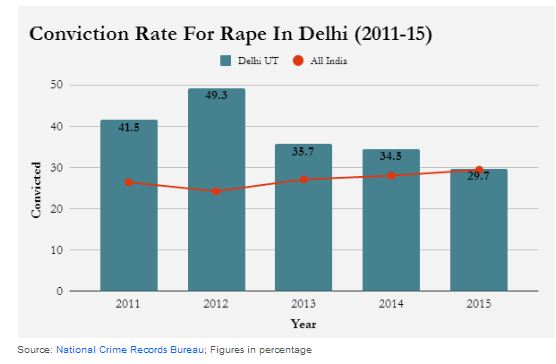

Meanwhile, the conviction rate for rape in Delhi, though better than the all-India average (see Table 2), dipped to 29.7% in 2015, the latest year for which data are available from the National Crime Records Bureau.

Across India, one in four rape trials leads to conviction, as IndiaSpend reported on March 9, 2015.

“Declining conviction rate in rape cases ordinarily means lesser number of registered cases could be proved in court and this gives rise to the suspicion that maybe false cases are also being registered,” Asthana said, “But it could also mean that police is not able to do good investigations or that victims are not getting quality legal representation during trial. Whatever may be the reason, declining conviction causes concern and must be examined for possible reasons.”

Government initiatives falter

After the Nirbhaya incident, the Delhi Police set up 161 help-desks staffed by female officers, and announced that 70% of female officers would report for over eight-hour shifts each day, according to 2014 Bureau of Police Research and Development study on national police working conditions. However, those who deal with these help-desks question their competence, IndiaSpend reported on August 12, 2016.

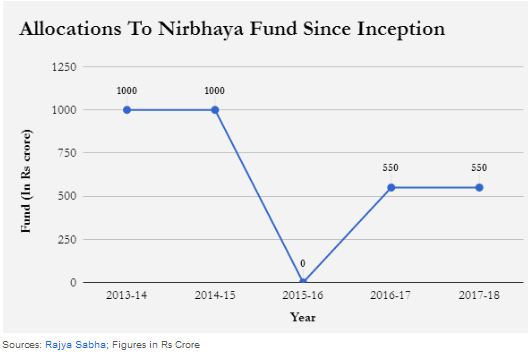

In 2013, the Ministry of Finance announced it would set up a Rs 1,000-crore ($156 million) Nirbhaya Fund to drive initiatives aimed at enhancing the safety of women in the country.

Thus far an amount of Rs 3,100 crore has been allocated, according to the government’s reply to the Rajya Sabha (upper house of parliament) on April 6, 2017. As many as 16 proposals amounting to Rs 2,348.850 crore have been received, of which 15 amounting to Rs 2,047.85 crore have been approved.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) has initiated three schemes under the Nirbhaya Fund—One Stop Centre (OSC) for women affected by violence, under which 84 centres are currently operational; Universalization of Women Helpline, under which 18 states and UTs have set up helplines; and Mahila Police Volunteer (MPV), whose pilots are currently running in several states.

Due to intense public scrutiny, the ministry issued a clarification on January 27, 2017, enumerating the various schemes being run by various ministries under Nirbhaya Fund. However, it made no mention of funds utilized or spent on these schemes individually, although an overall allocation of Rs 1,530 crore and an estimated expenditure incurred of Rs 400 crore was cited.

In a May 26, 2016, order, the Supreme Court asked the Centre to formulate a national policy for providing relief to rape survivors, saying the Nirbhaya Fund amounted to “just paying a lip service”.

Despite the initiatives under Nirbhaya Fund, crime against women continues unabated, amicus curiae and senior advocate Indira Jaising told the Supreme Court, The Hindu reported on February 7, 2017. “What is the purpose of having a fund when it does not reach the needy hands. It is hardly utilized and the only purpose it appears to have been used is setting up of ‘one stop crisis centres’ in different states,” Jaising said.

‘Societal attitudes must change’

Crime statistics from Delhi support this contention. Yet, laws and policing alone cannot prevent crimes of a sexual nature.

“Preventing sexual assault is a long-term process and the most important way to do so, is to change individuals’ and society’s attitudes and behaviour. Stringent implementation of laws and strict policing will help, but the real change will come when abusers and rapists are consistently convicted for their crimes, survivors are not doubted, judged or shamed,” Pinto said.

Pinto emphasized the need to change societal attitudes by instilling healthy notions of gender equality and masculinity among children, and removing unhealthy underpinnings of patriarchal biases among adults. This can only happen when “violence against women and girls is not considered a private matter, but a public problem, with societies, public and living spaces are designed and developed for women and children as much as for men,” Pinto added.

(Mallapur is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

This article was first published on IndiaSpend.