Athani, Belagavi: Dhondiram Tukaram Sutar, 68, a farmer and social worker from Pandegaon village in Athani taluka of northern Karnataka, has 2.5 acres of farmland on which he grows jowar (sorghum) every year. Jowar is a dry-land crop that can be grown in both rabi (winter) and kharif (monsoon) cropping seasons. Last year, Sutar’s entire crop failed due to scanty rainfall, and he has been unable to sow another crop ever since.

“Because there is no water, the crops have failed, and farmers are forced to sell their cattle,” says 68-year-old Dhondiram Tukaram (right), a farmer and social worker from Pandegaon village in Athani taluka of drought-hit Belagavi district of northern Karnataka.

Part of Belagavi district, Athani taluka is facing acute drought–from October 1 to December 31, 2018, Athani recorded 40.38 mm of rainfall against the average of 135.70 mm, while the district received 50.60 mm against the norm of 152.50 mm, according to data collected by the Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre (KSNDMC), an autonomous body affiliated with the revenue department of Karnataka government.

Athani has had scanty rains for more than a decade, inadequate to sustain agriculture, so that most farmers in the region rear cattle as an alternative source of income. Sutar has three cows and five goats. He sells their milk for Rs 30 a litre. He also breeds goats for meat and sells two every six months (a kid goat fetches Rs 4000–7,000, whereas a doe or a buck sells for Rs 10,000).

Now, there is not enough water to manage the cattle. Most farmers in the taluka who have had crop failures have been unable to avail of insurance payouts under the central government’s crop insurance scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY).

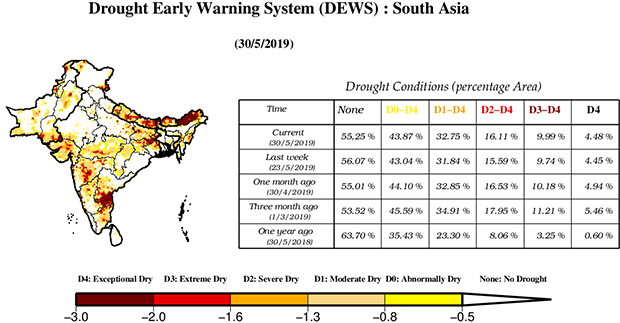

This is the sixth and last story in our series on the drought that affected at least 43.87% area in the country as of May 30, 2019, according to the Drought Early Warning System run by the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar. You can read the previous stories here, here, here, here and here.

Source: DEWS, IIT Gandhinagar; May 2019

Dry spell across districts

Karnataka declared 23 of its 30 districts drought-hit, IndiaSpend reported on September 28, 2018. At least 16 of these are perpetually drought-prone, according to an analysis by the Central Research Institute of Dryland Agriculture. These districts also feature among the 24 districts in the country that are known to be disposed to drought, revenue minister R V Deshpande told the legislative assembly in December 2018. Belagavi is identified as a permanently drought-hit region, The Hindu reported on December 19, 2018.

Due to prolonged drought, borewells, which are a primary source of water in the villages of Athani taluka of Belagavi district of northern Karnataka, have dried up, leading to the failure of water-intensive crops such as sugarcane.

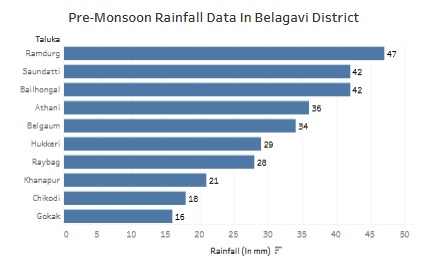

At least seven districts in Karnataka are marked ‘scanty category’—where the departure from average rainfall is between -99% and -60%, based on the pre-monsoon rainfall data (March 1 to May 31, 2019) collated by KSNDMC.

Source: Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre

Note: Data is between March 1 to May 31, 2019

Belagavi is one of the six districts recording rainfall of 31 mm, a departure of -68%. In Athani, the pre-monsoon rainfall was 36 mm; the departure from average rainfall, -52%. The situation is graver in the neighbouring talukas such as Chikkodi (18 mm rainfall, departure -80%), Raybag (28 mm rainfall, departure -63%) and Gokak (16 mm rainfall, departure -85%).

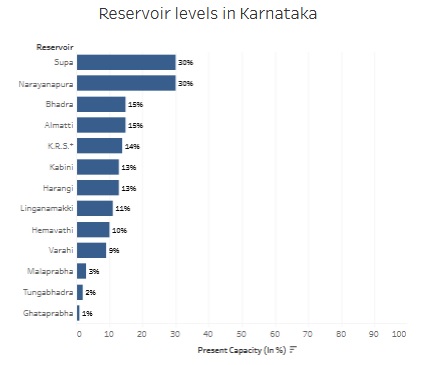

Source: Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre

* Height above Local Ground Level

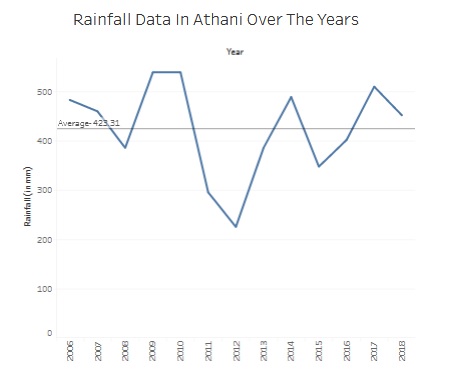

Athani has received only 34 days of rain on average every year—the lowest among the 10 talukas in Belagavi district—as per data collected by the Belagavi district statistical office between 1951 and 2000. This rainfall is concentrated in June, July and August.

The 10 rain gauges in the taluka show the drought situation worsening with each passing year. “Because there is no water, farmers are forced to sell their cattle,” said Sutar.

Rainfall in the northern Karnataka district also varies from year to year, according to H Venkatesh, agrometeorologist working on an All India Coordinated Research Project (AIRCP), under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research. While there might be good rainfall in June in one year, monsoons might start late in July the next year. “It rains regularly in October during the harvest season for short-term crops,” said Venkatesh. “We provide short-term and medium-term rain forecast. The extended long-term forecast is in an experimental stage. These predictions reach farmers through the Havaamaana Krishi mobile application.”

The KSNDMC has a 24×7, three-line help-desk called the Varuna Mitra, which provides weather-related information to farmers across Karnataka. “In 2018, we received about 1,525,000 calls out of which 52,471 calls were from farmers in Belagavi,” said G S Shrinivas Reddy, director of KSNDMC. The Indian Meteorological Department provides district-wise weather forecast while KSNDMC gives village-level weather information to farmers.

Pandurang Mane, 70, a farmer from Shirur village in Athani, grows maize and bajra (pearl millet) on 2.5 acres of land. Mane has not had a good harvest in the last two years due to insufficient rainfall. “The seeds that I had sown last year did not even sprout,” he said. Mane’s annual income from farming is around Rs 20,000. He gets by on Rs 5,000-6,000, which includes the money that his children send him. “With each passing year, my income is decreasing drastically. At my age, I cannot even get a job as a farmhand,” he said.

Digging for water an epic task

Almost 600,000 people in Athani depend on groundwater for all their needs—from drinking to farming–but groundwater has been depleted to the extent that borewells, of which every field has one, run dry too. There are a few open wells of about 120 feet depth, but to strike water, the well must go 700 to 800 feet deeper, for which permission has to be taken from panchayats.

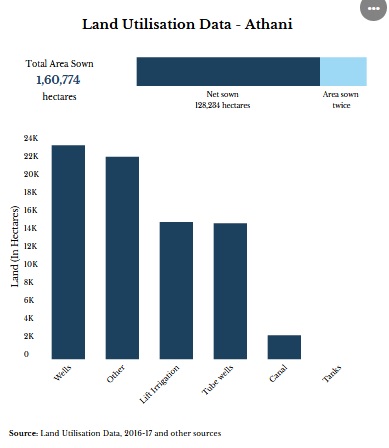

Source: District Statistical Office, Belagavi

“Borewells are not serving their purpose anymore,” said A V Manjunath, assistant professor and an expert on agricultural water management at the Institute for Social and Economic Change. “Moreover, the quality of borewell water is also poor due to high fluoride [content].” The levels of fluoride and nitrate in the water are beyond healthy limits, according to a report on a water management plan for Athani taluka published by the Central Ground Water Board in March 2017.

Further, dams in areas such as Kolar and Chikkaballapur have also dried up.

Situation in border villages

Nearly 88.6% of Karnataka is drought-hit—156 of 176 talukas. A joint survey to estimate the loss endured in the rabi season was to be conducted by the state and central governments. However, villagers said, the teams had not yet visited all the villages, particularly those that border Maharashtra. Although a few primary facilities such as fodder banks and tanker water supply have been initiated, their availability has been insufficient, according to the Belagavi district administration’s survey reports, which IndiaSpend has reviewed.

Without drinking water, fodder for cattle, water for irrigation and a source of livelihood–jobs under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) have also been scarce–villagers living close to the border are migrating to villages such as Kavathe-Mahankal, Dhulgaon, Salgare, and Mahalunge in Sangli district of Maharashtra. The fields in the neighbouring state are “well-irrigated”, and it is “easy to find work,” villagers told IndiaSpend.

Compensation for crop failure

“The seeds that I had sown last year did not even sprout,” says 70-year-old Pandurang Mane (left) from drought-hit Athani taluka in northern Karnataka. His income has been reducing every year, he says, and he cannot get work as a farmhand at his age.

Water-intensive sugarcane is a major commercial crop in Athani, in a self-destructive pattern well-known throughout arid Karnataka–farmers continue to cultivate sugarcane for its potentially more lucrative returns, making it the country’s third largest sugarcane producer and accounting for 16% of India’s sugar production. Currently, it is cultivated only in areas situated near the banks of the Krishna river.

Several dryland crops, such as cotton, maize, jowar, bajra, ragi, wheat and Bengal gram, are being grown in areas that do not have easy access to water. Villages such as Ainapur, Shirhatti, Saptasagar, Shankaratti, Darur, and Satti, which are close to the Krishna river and are conducive to growing water-intensive crops, are thriving when compared to villages such as Jambagi, Ajur, Madabhavi, Pandegaon, Malabad, Shirur, Anantapur and Shivnoor that are situated far away from the river and receive scanty rainfall.

Total crop loss in Athani due to lack of water during the rabi season (2018) is 34,604 hectares (of 1,60,774 hectares of the sown area). Some 23,375 farmers were to receive compensation of Rs 2,353.08 lakh combined, under the National Disaster Response Fund and State Disaster Response Fund, based on a survey report by the central team. However, the funds for this have not been released yet.

The PMFBY crop insurance scheme witnessed the highest number of enrollments in Belgaum district. In 2016 alone, 140,089 farmers enrolled for the rabi season and 31,538 for the kharif season. This number fell in 2017 with only 1,910 farmers enrolling for the rabi season and 151 farmers in the kharif season because of good rainfall during that period.

In 2018, 1,849 farmers from Athani enrolled for crop insurance during the rabi season and 8,547 during the kharif season. However, farmers have been paid compensation only for the period until 2016. Farmers who faced crop failure in 2017 and 2018 are yet to be compensated because the central government has not released the funds, district collector S B Bommanhalli told IndiaSpend.

No fodder for cattle

In Khilegaon village, there are no fields for the cattle to graze. “We are entirely dependent on fodder banks to raise our cattle,” said Annappa Nimbal, 55, a native and farmer in the village. Mane, who owns four cows, nodded in agreement. The fodder bank in Shirur village, which opened on February 2, 2019, caters to Shirur, Sambaragi and Pandegaon villages. More fodder banks have opened in Mole, Khilegaon and Ajur panchayats.

With no rains and limited or no stock in fodder banks, farmers of Athani taluka either send the cattle to their relatives in neighbouring Maharashtra or let the cattle wander in search of whatever greenery is available.

To avail of fodder, the farmers have to provide Aadhaar cards and record the purchase in a book, acknowledged by the accountant. Veterinary officers provide officials with a list of farmers in each village and the number of cattle they own. “This ensures the provision of real-time requirement of fodder and prevents misuse of fodder funds,” said M B Patil, 35, who is the talathi (village accountant) at the revenue department in Shirur talathi office. In Shirur village alone there are 2,200 cattle. About 180 farmers avail the services of the fodder bank regularly.

Each animal is given 15 kg of fodder at a price of Rs 1 per kg for wet and Rs 2 per kg for dry feed. However, for a healthy cow to provide enough milk, it needs at least 20-25 kg of fodder per day, said the villagers. Sometimes, the farmers send the cattle to their relatives’ places in Maharashtra where there is enough water and fodder.

Sugarcane bagasse from the sugar mills is the primary source of fodder and comprises 1,518 tonnes of sugarcane brought to each fodder bank. However, when the mills close during the summer, there is a shortage of feed. Earlier, there were goshalas (cow shelters), but the concept has been shelved for the past five years. “It should be brought back,” said Sutar.

Earlier, farmers could deposit their cattle in goshalas, that were run by a task force comprising panchayat development and revenue officials. These were replaced with fodder banks five years ago.

Farmers are forced to walk for three to four kilometres to the nearest fodder bank. “As the drought situation continues to worsen, more fodder banks will be opened in Sambaragi and other villages,” said Patil, the talathi.

Job creation critical during drought

“Although we have agricultural land, we are unable to till it. We are also not getting any jobs under MGNREGA scheme. We are living a dire life,” said Nimbal, the Khilegaon farmer. With no options left, villagers migrate to neighbouring Maharashtra in search of work in farmlands and construction sites. Mane from Shirur has two sons who along with their wives, do odd jobs in Miraj and Sangli in Maharashtra. “They come to the village once a month,” Mane said.

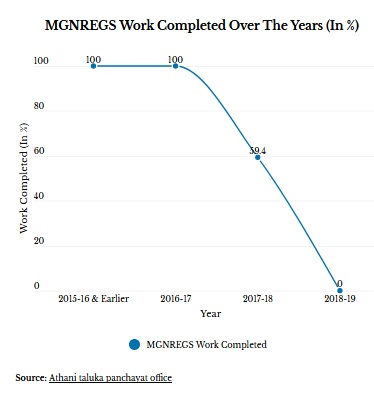

Gram panchayats have stopped undertaking new works under MGNREGS, and the percentage of works completed under MGNREGS has decreased over the years. Officials claim there is no budget allocation for new development works. In Athani, the number of job cards issued is 3,226, and there are 1,403 registered active workers, according to the MGNREGS website. However, the number of registered active workers is only 281 in the current year.

“The zila panchayat needs to undertake bund construction works in the villages. It will help in rainwater collection in drought-affected regions and will also create job opportunities,” says Shivaji Kaganikar, 55, an activist from Belagavi.

MGNREGS is an important lifeline for people in rural areas since the scheme assures 150 days of guaranteed employment in a year in drought-affected areas. “MGNREGS is the only programme which will help poor people in the drought-ridden areas get two square meals a day,” said Shivaji Kaganikar, 55, an activist with the NGO Janajagaran and a member of the Bhrashtachar Nirmulan Samiti, an anti-corruption NGO, in Belagavi.

However, some villagers IndiaSpend spoke to said jobs are not given until rural women fight for it in large numbers. Wages are not paid on time, and corruption is rampant, they said. In some areas, people create fake job cards and bank accounts, said Kaganikar. The zila panchayat should undertake bund construction works under MGNREGS for rainwater collection in drought-affected regions, which will also create job opportunities, he said. There is a need for greater transparency and to create awareness about the programme.

Flawed water schemes

Government water tankers are supposed to provide 40 litres of water per person every day, but the villagers complain that they get only 15-20 litres (two to three pots). A queue at a water tanker in Mole village of Athani taluka in northern Karnataka.

Savitri Rokade, 45, a housewife from Ugar Khurd town, Athani, recently led an all-women protest march against the shortage of drinking water. She blamed politicians for the water problem: “This has been going on for a few years, and the authorities have not been able to find a permanent solution to resolve this issue. Rich people can buy a pot of water for Rs 20. How can the poor quench their thirst and tend to their cattle? Authorities should provide enough water tankers to villages until the water scarcity ends.”

The Multi-Village Water Scheme (MVS) of the state government, which supplies river water to villages, brings drinking water to Athani villages from the Krishna river. However, when the river dries up in the summer, the scheme becomes dysfunctional, and Athani and Kagwad talukas suffer the most. This “design flaw” exists in various water schemes, Krishna Byre Gowda, the rural development and panchayat raj minister, was reported to have acknowledged at a press conference on May 18, 2019. He said that around 75 water schemes have stopped functioning due to lack of water and the absence of a back-up plan.

Making the situation worse, the Maharashtra government is not releasing water from the Koyna dam to the drought-hit villages in north Karnataka as it had done in previous years.

Water levels in Karnataka’s 13 reservoirs are down to 13.38% of their overall storage capacity, as per the KSNDMC.

A Basaveshwara-Kempwad lift irrigation project in public-private partnership mode aims to irrigate about 27,462 hectares in Athani at a cost of Rs 1,363 crore ($204.88 million). It will lift water from the left bank of the Krishna to cater to about 20 villages. However, the project will take at least three and a half years to become functional, M Shrinivas, an official associated with the project, told IndiaSpend.

In the last five years, the centre has cut 64% of the funds to Karnataka under the National Rural Drinking Water Project. The Centre’s contribution in 2018-19 has fallen to Rs 312.33 crore from Rs 868.76 crore in 2013-14, the Deccan Herald reported in February 2019.

With Athani experiencing persistent drought for the last 14 years, the bunds (embankments made to prevent runoff and store rainwater) and lakes have gone dry. The government is desilting some of the lakes, but is yet to install the pipeline that would carry water from the Krishna to the lakes during the monsoon.

Government water tankers are supposed to supply at least 40 litres of water per person every day. However, the villagers claim that they get only 15-20 litres (two to three pots)–not enough for bathing, washing or watering the fields, so they end up using drinking water for these activities.

Insulating against drought

Successful dryland agricultural practices can help conserve moisture in the soil, which can last to some extent during dry spells. “To increase productivity or to get a good yield, even during drought, the farmers should plough vertically at low-lying land so that the rainwater gets harvested in the fields during monsoon, which helps to maintain soil moisture,” said Surakod V S, senior scientist of agronomy at AICRP.

In the rabi season, farmers should cultivate land in small square patterns while sowing seeds, which helps retain water and maintain soil moisture, Surakod said, adding that the farmers in Hanawad village in Vijayapura near Athani have been getting good yield by practising this method even during drought.

Micro-irrigation techniques, such as drip irrigation and sprinklers, can facilitate feasible agriculture in drylands. “People think that if surface water is readily available through canals, why should they opt for drip irrigation. However, people living away from canals always get less water. If farmers living upstream used drip irrigation, those living downstream would not experience severe water stress,” said Manjunath.

Traditional and easy techniques such as mulching can also help retain soil moisture and conserve water. Bunding is another technique to store rainwater and prevent run-off. Aggressive investments in soil and water conservation programmes are a must to mitigate Karnataka’s drought situation.

This concludes our six-part series on drought. The previous stories can be read here, here, here, here and here.

(Shankar is a Belagavi-based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.)

Courtesy: India Spend