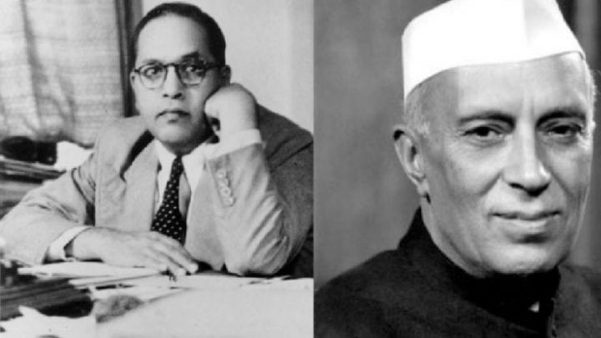

Was it really the way as made out to be by Home Minister Amit Shah? Was Nehru’s reaction to Ambedkar’s resignation over the Hindu code bill, a moment of relief for the former, India’s first Prime Minister as the present Home Minister says? What were his (that is the Home Minister’s) own antecedents, persons from the RSS[1] doing at that time? His remarks have sparked a debate in the public sphere. The entire issue remains shrouded in layers and complexities, only unravelling of which may form the basis of any truth. Ambedkar believed Nehru to be the most sincere among all Congressmen on the question of the Hindu Code Bill. The fact is that the RSS opposed it tooth and nail. The Home Minister has portrayed how Ambedkar was not accorded the respect and honour that he deserved, by Nehru but that is contrary to the truth. Let us closely investigate this charge and with it also bring out in public domain the negative role played by communal forces during the debates around the Hindu Code Bill.

History of the Hindu Code Bill

Talks about a Hindu Code Bill had emerged since the 1920s itself. The AIWC (All India Women’s Conference) demanded a revision of the Hindu Code to overcome deficits in women’s rights. This was the crucial difference between the reforms of the 19th century which were piloted from above and these, which were reforms actively sought by the women themselves. The AIWC declared a Women’s Legal Disabilities Day in 1934 at the instance of Renuka Ray. The Hindu Women’s Right to Property Act was then tabled by its author G.V. Deshmukh in the Central Legislature.

The same year, the Shariat Application Bill tabled by H.M. Abdullah was passed which gave the daughter a share in property. However, in both the Hindu and Muslim case agricultural land was exempted from the application of the respective bills. This was because agricultural property fell under the ‘jurisdiction of provincial legislation’ while these two Acts of 1937 were Central legislations. (Chitra Sinha, Debating Patriarchy:The Hindu Code Bill Controversy in India 1941–1956, 2012). Why was this the case? Probably, the vote-influencing elite class couldn’t be touched or angered!

However, the demand for codification of Hindu personal law driven by Hindu women did gain legitimacy with the 1937 “Deshmukh Act.” A Hindu Law Committee was appointed on January 25, 1941 headed by B.N. Rao (who went on to become the constitutional advisor of the Constitution’s drafting committee). Other members were- Shri Dwarakanath Mitter, ex-Judge of the Calcutta High Court, Shri R. Gharpure, Principal, Law College, Poona and Rajratna Vasudev Vinayak Joshi, a lawyer from Baroda. The committee appreciated the role of Women’s Associations across the country. The committee suggested two measures in its final report submitted in June 1941. These were largely related to an enlargement of the terms of reference and the need for provincial legislative changes to apply to the Hindu Women’s Right to Property Act in agricultural landed property.

With these suggestions in mind two draft bills on the law of marriage and inheritance were prepared and presented before a joint committee of both the houses. The two bills together came to be known as the draft Hindu Code Bill and were presented before the Legislature to be debated in 1943-44. The Committee was invoked again and began working from 1945 onwards. Dwarkanath Mitter presented a dissenting opinion stating that of the total number of people interviewed for the bill, only 33.4% supported the codification drive [the percentage being even smaller in the “Hindu Heartland” (coined by Gyanesh Kudasia)]. The figures are from the Report of the Hindu Law Committee, 1947.

Maharashtra offered the greatest support in favour of the Code Bill. Dharma Nirnay Mandal (formed at Lonavala in 1936) which was at the forefront went to many places in Maharashtra raising awareness on the codification issue. It brought out several publications including Why Hindu Code, co-authored by T.K. Tope and H.S. Ursekar. The Hindu Code Bill was thereafter referred to the Select Committee in April 1948. The ball was now in Ambedkar’s court.

Views of Ambedkar and Nehru on the Bill

Ambedkar believed the Code Bill to be a vehicle towards reforming Hindu society. He therefore considered the Hindu Code Bill as historic as the Constitution making process. He spoke of the aims and objectives of the bill in the simplest of terms to make it accessible to all. He stated that – “in order to reduce the confusions surrounding Hindu laws and also to make these more equitable and relevant to contemporary Indian society, the Bill seeks to codify the law relating to certain aspects covering marriage, property, succession etc.”

With these essential points in mind, let us now move to see the people who opposed the Bill who have been grouped into categories by Reba Som in her article ‘Jawaharlal Nehru And The Hindu Code: A Victory Of Symbol Over Substance?’(Modern Asian Studies, February 1994). We shall simultaneously accentuate the contradictions and paradoxes of these people on the issue which exposes their hesitance for reforms and their unwavering commitment to not want women being treated at par with men. These were-

One. Those stalwarts within the Congress who had been arrayed against the likes of Nehru from 1930s onwards. These were represented by Rajendra Prasad who had been unhappy over the issue since the start. Prasad believed that the progressive idea of introducing basic changes in personal law was only the view of a microscopic minority and its imposition on the Hindu community as a whole would have disastrous consequences. When frustrated by Prasad and others in the assembly over the issue of the bill, Nehru told them that the passing of the bill had become a matter of prestige for him. Prasad had drafted a letter in response to this on which he consulted (luckily for him), Vallabhbhai Patel before sending it. Patel counselled him on the benefits of remaining quiet as this would brighten his chances of being elected the first President of India. Prasad thus, kept quiet and got elected the first President. However, once he assumed this constitutional role, his obduracy over the bill continued, sometimes citing procedural lapses on Nehru’s part (for which there was no provision but only convention) and sometimes by terming the efforts at getting the bill passed as anti-democratic. He in fact, even threatened to withhold Presidential assent to the Bill even if it was passed from both the houses. Surprisingly, Prasad was the President when, later, in five parts the Hindu Code Bill was largely passed by Indian Parliament.

Along with the likes of Prasad were Hindu fundamentalists within the Congress like the Deputy Speaker, Ananthasayanam Aiyyangar who was convinced of the soundness of polygamy. This group never made an earnest effort to carry through the reformist agenda Congress propagated. Some among those who were not so opposed to the contents of the Bill were at sixes and sevens because of the fact that the Bill was piloted by Ambedkar, an untouchable. Pattabhi Sitaramayya, a liberal member of the Congress too criticised Ambedkar for his “professional, pedagogic and pontifical attitudes” which will “only alienate attitudes that have almost been reconciled,” records Reba Som.

Two. The Hindu Mahasabha with people like N.C. Chatterjee and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee who opposed the Bill based on the fact that it threatened the very foundation of Hindu religion. The Mahasabha tried to argue that the “Hindu” Code Bill was a communal legislation (only for the Hindus) and instead that a Uniform Civil Code should be introduced in its place. Thus, it becomes clear that it was not out of a progressive reformist zeal that the Mahasabha wanted a Uniform Civil Code but only so that the state power interferes in Muslim affairs as well. Mukherjee argued that the Hindu Code be made optional, an argument similar to what Jinnah made during the passage of the Shariat Application Bill 1937. Mukherjee had been in Nehru’s cabinet and wholeheartedly supported the Code which he was now opposing and therefore, Ambedkar dismissed his remarks as non-worthy of consideration.

Within this category let us add a subcategory of Hindu reactionaries outside the Parliament represented by the RSS. In March 1949 the All-India Anti-Hindu-Code Bill Committee with Swami Karpatriji Maharaj at its head was formed which opposed the Constituent Assembly’s interference in personal laws of Hindus based on Dharma Shastras. (Ramchandra Guha, India after Gandhi, 2008) Alongside this Committee was also a battery of lawyers from various Bar Councils across the country who absolutely condemned the Code Bill. The Committee held several hundred meetings throughout the country opposing the Bill. The All India Hindu Code Bill Virodha Samiti even published a book, Hindu Code Bill: Praman Ki Kasauti Par in Hindi by Swami Karpatriji Maharaj, condemning the government propaganda about the Bill and presenting the Bill in complete opposition to the ideology of Sanatan Dharma. (Chitra Sinha, 2012) This Committee even marched on to the Parliament raising derogatory slogans like “Down with the Code Bill” and “May Nehru Perish.”

Three. The Sikh group represented by men like Sardar Mann and Sardar Hukum Singh inside the Parliament and Master Tara Singh outside it, who resented being clubbed with the Hindus in the broad framework of reform. Tara Singh denounced the introduction of the Hindu Code Bill in the Parliament. This can be found dated 13th December in G. Parthasarathi edited Letters to Chief Ministers Vol.2 1950-1952. Interestingly, after Ambedkar had resigned and not much alteration had been made to the Bill, Sardar Hukum Singh stated that the Bill could now be passed as the objectionable parts had been removed.

Four. Muslims represented by Naziruddin Ahmad from Bengal who argued that the Hindu Code Bill was a bid to end the Mitakshara joint family. This would lead to division of families and property issues. The most baffling part is that despite hailing from Bengal which was the epicentre of Dayabhaga School, Naziruddin Ahmad chose to speak about Mitakshara. Even more fascinating is the fact that provincialism, evoked by Jinnah during the debate on Shariat Application Bill 1937, was ensured among Bengali legislators by the very same Naziruddin Ahmad. Of the scant information on him over the Internet, his appointment as the chief whip by A.K. Fazlul Haq, then Bengal chief minister is surely significant. The same provincialism is found wanting in Naziruddin Ahmad while speaking on the Hindu Code Bill. When he remarked that Hindu families would suffer the same fate as Muslims, he was given a shut up call by Renuka Ray who asked why he was not ready to let the Hindus enjoy the same advantages that the Muslim society enjoys.

Six. Women Parliamentarians, largely the ones who were consistent in their approach and most fully committed to get the Code Bill passed. Even their criticism, expressed through Sucheta Kriplani and Hansa Mehta, was sound and logical based on the fact that the reforms did not go as far as they should have and that they were half-hearted.

Ambedkar’s resignation and his assessment of Nehru

Correspondence between Ambedkar and Nehru on the topic brings out the differences in views as well as approach to the Hindu Code Bill. On August 10, 1951, Ambedkar wrote to Nehru-

“My health is causing a great deal of anxiety to me and to my doctors. They have been pressing that I must allow them a longer period of about a month for continuous treatment and that such treatment cannot now be postponed without giving rise to further complications. I am most anxious that the Hindu Code Bill should be disposed of before I put myself in the hands of my doctors. I would, therefore, like to give the Hindu Code Bill a higher priority by taking it up for debate and consideration on August 16 and finish the matter of by September 1, if the opponents do not practice obstructive tactics. You know I attach the greatest importance to this measure and would be prepared to undergo any strain on my health to get the Bill through.” (Selected Writings of Ambedkar)

Nehru however, knew that the conservatives were too many and quite vehement in their opposition to the Hindu Code Bill. There was now no Patel to ensure the whip in support of the measure. However, Ambedkar did not pay attention to this view and he felt extremely frustrated that Nehru wasn’t able to get the Bill passed. The fact remains that with the active support of the then President, many members including the chief whip were all firm in their disapproval of the Hindu Code Bill. Nehru could not hurry it through since elections were also round the corner. As Ambedkar sarcastically put it, ‘I have never seen a case of chief whip so disloyal to the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister so loyal to a disloyal whip.’(Reba Som, 1994) Ambedkar was, however, convinced of Nehru’s sincerity, it was only his lack of determination that he criticised.

There were a few more issues (not connected to Nehru directly) over which he resigned. Nehru’s sincerity is reflected in a letter he wrote to the Chief Ministers on October 4, 1951. He stated- “it was obviously a controversial measure and it was not our desire to suppress debate or even to treat this as a strictly party measure necessitating a Whip.” He cites this as the reason for failure to get even parts of the Bill through. He goes on to say, “I have no doubt that a considerable majority in Parliament desired the passage of this bill with minor alterations. But that majority was helpless before a determined minority and we had to confess defeat. For the moment at least I do not think, however, that all this time on the Hindu code bill has been wasted. It has kept this important subject before the public and made people think about it. It had made it one of the major issues in India and I have little doubt that it will have to be taken up and passed sometime or the other. For my part I am convinced that progress in India must be on all fronts- political, economic and social. Unless this happens we shall get held up.”

Nehru’s reaction to Ambedkar’s resignation

Frustrated and flabbergasted over the stoicism of conservative elements within the Congress, Dr. Ambedkar rendered his resignation on September 25, 1951. On his resignation, Nehru spoke in the Parliament with a sense of loss. “It is a matter of regret for me, if for no other reason, for the fact that an old colleague should part company in the way he has done today.”

Moreover, Nehru wrote to Ambedkar on September 27, 1951 with mixed feelings of appreciation for Ambedkar’s efforts and determination on his part to get the Bill through sooner or later. He wrote,- “I can quite understand your great disappointment at the fact that the Hindu Code Bill could not be passed in this session and that even the marriage and divorce part of it had ultimately to be postponed. I know very well how hard you have laboured at it and how keenly you have felt about it.” Nehru goes on to state that “I tried my utmost, but the fates and the rules of Parliament were against us.” He promised to keep fighting stoutly, “personally, I shall not give up this fight because I think it is intimately connected with any progress on any front that we desire to make.”

Conclusion

Eventually, when the Hindu Code Bill was passed in various parts in 1956, Nehru offered his tribute to Ambedkar. He stated that Ambedkar would be remembered above all ‘as a symbol of the revolt against all the oppressive features of Hindu society’. But he “will be remembered also for the great interest he took and the trouble he took over the question of Hindu law reform. I am happy that he saw that reform in a very large measure carried out, perhaps not in the form of that monumental tome that he had himself drafted, but in separate bits.” (Ramchandra Guha, 2008)

The glowing tribute by Nehru to Ambedkar and Ambedkar’s admission of Nehru’s sincerity of efforts says it all. It was not these two but rather “the orthodox of all religions united” (from the title of Jawaharlal Nehru’s Essay) who were pitted against them on the issue of Hindu Code Bill. What’s more concerning is the remark heard from certain quarters of the Parliament after the passage of the Hindu Code Bill. During 1955 and 1956, when the Hindu Code Bill was enacted in fragments, Ambedkar’s absence was cited as a reason for the smooth passage of the Bill. (Chitra Sinha, 2012) Throughout the trajectory of the Hindu Code Bill, Nehru and Ambedkar remained consistent in pushing for reforms. Therefore, this struggle for the Hindu Code Bill and those who opposed it and actually disrespected Ambedkar should be clearly identified. Lest History Forget!

(The author is a PhD Candidate at the department of history, AMU)

[1] Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh formed in 1925

Related:

Dr BR Ambedkar: How the ongoing tussle between the BJP and Congress is both limited & superficial

What Nehru Flagged as ‘Most Dangerous’ Modi Now Invokes for Votes

Nehru’s Prescient Words During 1st General Elections Resonate Today

Iconoclast: Path breaking biography of BR Ambedkar projects his human essence