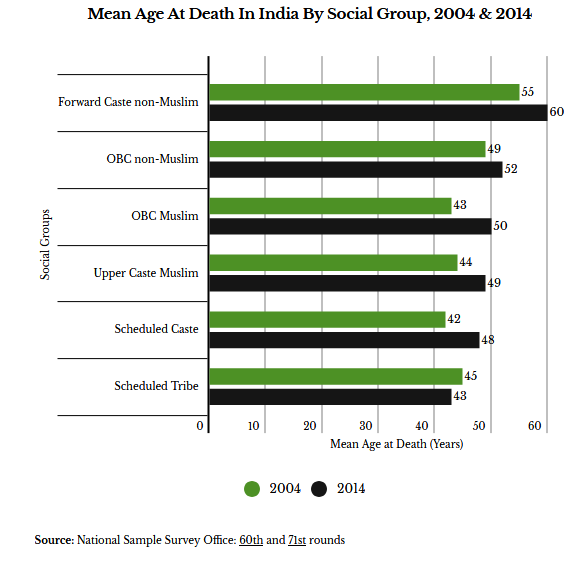

Mumbai: At 43 years, the mean age of death for adivasis (scheduled tribes or STs) was the lowest, meaning they were more likely to die before other Indians, according to a new paper.

Apart from adivasis, if you feature on the bottom of the social ladder in India, or are dalit (schedule caste or SC) or Muslim, you are more likely to die younger, suffer poor health and have low access to healthcare compared to those belonging to the non-Muslim upper class, found the analysis “Caste, Religion, and Health Outcomes in India, 2004-14” by economist Vani Kant Borooah, published in the Economic & Political Weekly on March 10, 2018.

Over the decade to 2014, all social groups, except adivasis, were living longer than in 2004–the mean age of death for STs had reduced since 2004 when it was 45 years.

Dalits, whose average lifespan was 42 in 2004, were likely to live six years longer by 2014, the analysis found.

Non-Muslim households of the upper classes appear to live the longest among the six groups with a mean age of death of 60 years in 2014–up from 55 years in 2004.

“The point about group membership is that while it may not be the primary factor behind health inequality, it is the main cause of health inequity,” Barooah wrote, adding that the inequity refers to the inequality an individual suffers because of factors beyond their control.

To evaluate the relative role a person’s economic and social status plays in determining his/her health status in India, Barooah used National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) datasets from 2004 and 2014. Combining the NSSO “social group” and “religion” categories, households were split into six groups: adivasis of which 56% were Hindu and 33% were Christian; dalits of which 93% were Hindu; non-Muslim other backward classes; Muslim other backward classes; and non-Muslim upper classes.

In non-social group variables–categories unrelated to caste and religion–the average life of a labourer (45.2 years) was more than three years shorter than that of a non-labourer (48.4 years), the analysis found. Similarly, living in a “backward” or less-developed state reduced the average age of death (44.4 years) by over seven years compared to living in a “forward” or more developed state (51.7 years).

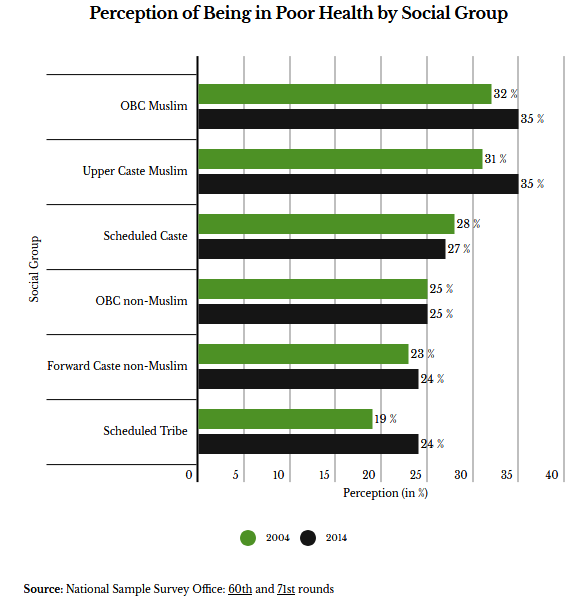

Adivasis least likely to report being in poor health; Muslims most likely

Despite adivasis dying younger than other social groups, least among them felt they were in ill-health (24%), though the numbers reporting sick had risen from 19% since 2004, according to the study, which also analysed NSSO data on the perception of current health status among senior citizens (aged 60 years and above) across social groups. This was the same among persons of the non-Muslim upper class group, which had minimally changed since 2004 (23%).

The status showed whether these persons reported to be in excellent, very good, fair, or poor health, allowing the study to calculate a predicted probability of poor health (PPPH).

Most to report being in poor health, or 35%, were Muslims–both OBC and upper class–the data showed.

More women (28%) than men (24%) reported to be in poor health, the study found.

Among non-social groups, the predicted PPH was significantly higher for persons in “wage labour” households (29%) than for those self-employed or earning regular salaries (26%), the study found.

In 2014, people in urban areas were more likely to report being in poor health (28.7%) than their rural counterparts (25.3%) though this was not the case a decade ago when rural (24.3%) and urban (24.5%) residents shared similar views.

Also, fewer persons in “forward states” were likely to report being in poor health (24.2%) than those in “backward” states (29.2%), the analysis showed.

Poor, single persons more likely to report being in poor health

The economic circumstances of a person’s household also played a role in determining the predicted PPH, the study found. Persons in households belonging to the lowest two wealth categories were significantly more likely (over 27% for both) to report being in poor health than persons in the highest wealth category (25.4%), NSSO data show.

Access to flush or septic tank latrine in the house reduced the predicted PPH (24.6%) compared to the perception of persons with access to latrines of other types or no latrine altogether (27.9%), the study found.

Similarly, cooking with gas or electricity (24.4%) compared to other fuel types (27.8%) significantly reduced the predicted PPH.

Personal attributes too played an important role in determining a person’s predicted PPH.

For example, married persons had a lower predicted PPH than those who were single, widowed or divorced, according to the study, which also found the predicted PPH of illiterate persons (27.9%) was significantly higher than that of graduates (18.3%).

(Saldanha is an assistant editor with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend