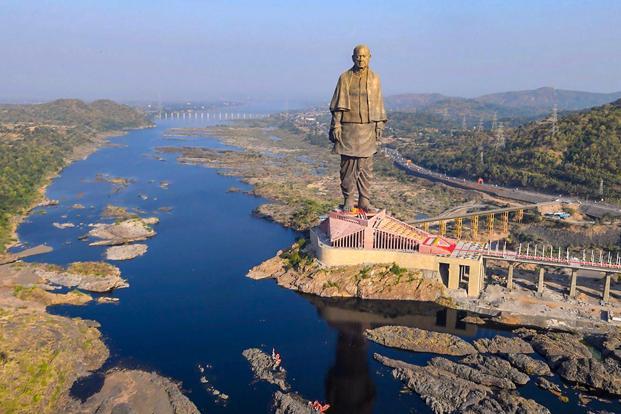

The recently enacted ‘Statue of Unity (SoU) Area Development and Tourism Governance Act, 2019’ in Gujarat comes amidst a terrifying atmosphere of intimidation, house arrests, detention and, FIRs, not to mention the overarching implementation of Section 144 across the state.

On the face of it, the SoU Act is an innocuous law intended to promote tourism around the giant statue of Sardar Patel. But its actual aims are anything but benign. Even a plain reading of the Act makes it clear it is tailored towards uprooting the local tribals from their own villages and livelihoods, and systematically rendering them stateless.

Tourism promotion at any cost

The ‘objectives and reasons’ for the new law reveal its true intent – everything is being done for tourism. It reads:

“Since its dedication to the Nation by the Hon’ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi on the 31st October, 2018, [the Statue of Unity] has emerged as one of the most favorite tourist destinations in the country. Surrounded by the serene environment with Vindhyachal and Satpuda mountain ranges on either side, this place has become a prominent family tourist destination with addition of a number of allied attractions like Valley of Flowers, Vishwa Van, Jungle Safari, Cactus Garden, Butterfly Garden, Ekta Nursery, Arogya Van, Zarvani Eco-tourism & adventure sports, Khalwani Eco – tourism site, Ekta Mall, Ekta Auditorium, Children Nutrition Park, Mirror Maze, Ekta Food Court and various accommodation facilities. Around 30 million tourists have visited this place in a short spell of about 13 months. […] Therefore, the State Government has deemed it fit to establish an Authority… which would ensure expeditious and planned development of the area, provide appropriate civic amenities and regulate tourism activities so as to provide secure and safe tourism for the tourists.”

In the name of development, the Act focuses so heavily on tourist facilities that in the entire text there is not even a mention of the original actual/original inhabitants of the area – the tribals. The word ‘tourism’ is mentioned in the text 154 times and ‘tourists’ seven times. But there is no concern expressed for the local tribals’ loss of land and livelihood, much less any solution provided to how the displaced will be compensated and their rights restored.

The Act is written as if there was no human habitation around the Stature of Unity and the government of the day discovered a virgin area by chance and decided to explore its tourism potential to the full. To call this “development” is to insult and mock the term.

Environmental, wildlife, wetland laws not to apply

Looking at the SoU Act, one might conclude that the area it covers is not part of India, and, therefore, the following laws do not apply to it: (1) The Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972; (2) The Environmental Impact Assessment Notification 2006; (3) The Environment (Protection) Act 1986; (4) The Wetlands (Conservation and Management) Rules 2010; (5) The Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016; (6) The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974; (7) The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, (8) The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014. Excluding the SoU area from these laws, and for no valid reason, is blatantly unconstitutional.

For the government, the multi-crore SoU and related tourism projects might be a dream fulfilled. But the hidden reality of the project is that it will rob indigenous people of their homes, lands and traditional livelihoods, and will almost certainly damage the Narmada river ecosystem, the biodiversity of the region and the Shoolpaneshwar Sanctuary, as well as the flow to the downstream river. The potential harm to the ecological structures and functions in and around the area will place an enormous burden on the local people and extract a huge price from them in an era of worsening climate crises.

To ensure the Act’s implementation, the government has adopted a multi-pronged approach of complete surveillance, intimidation and suppression of rights of the local villagers and concerned citizens. Non-state actors have been deployed by the government to create an atmosphere of extreme fear in the 72+ villages that are impacted by the SoU and related projects and the six plus villages that have been vacated “voluntarily”. Kevadia and the SoU area are in a state of panic with rampant violations of the law and the basic principles of human rights, freedom of expression and freedom of movement.

Adivasis as ‘occupiers’

Under section 2. (I) (i)), the Act refers to the original inhabitants – the local tribals – as ‘occupiers’ To quote:

” ‘occupier’ includes, … (ii) an owner living in or otherwise using his land or building; … but, shall not include a person who on the date of commencement of this Act is in illegal possession of any land which has been acquired by the State Government or by any other authority and has vested in the State Government and shall not also include a person who has encroached upon such land;”.

The constitutional provisions of Schedule V for forested areas inhabited by indigenous tribals and the Panchayats Extension to Scheduled Area Act, 1996 (PESA) – both of which apply to this area – are completely missing from this Act.

PESA in Gujarat exclusively empowers the gram sabha to implement certain crucial tasks like approving any plan, project or programme for the development of the village, and selecting beneficiaries under the poverty alleviation and other programmes. The present Act eliminates the power of the gram sabha for reasons that should be self-evident. It is starkly evident that the Act has been created in order to appropriate the powers and mandate conferred on local self-governing institutions by the 73rd and 74th amendments to the constitution and extension of PESA in the region.

Interestingly, Section 2. (c) of the Act describes a developer thus:

“’developer’ means a person or entity with whom a concession agreement is entered into or a project has been awarded and for which such other agreement is entered into for furtherance of the objectives of this Act;…” It is crucial to note that the Act talks of ‘Concession Agreement’. Section 2(e) of the Act states, “ ‘development plan’ means a plan for the development or re-development or improvement of a Tourism development area.”

There is no obfuscation of intent here. Development means tourism development and not the development of or for the local people of the area.

Forest to urban area with the stroke of a pen

Further, the Act converts a forested region into an urban area for tourism with no representation of tribals or even administrative representations vide the departments related to tribal affairs, rural areas, and the environment; instead, the Act mentions departments related to urban, tourism, town planning, etc.

Under section 2(b), the Act states that “‘building operations’ shall have the same meaning as is assigned to it under clause (vi) of section 2 of the Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act, 1976..;” which makes it clear that ‘Schedule V’ area has been unconstitutionally converted into an urban town area.

The Act states in section 31 (1)

“The State Government may, having regard to the proviso to clause (1) of Article 243Q of the Constitution of India, consider the Tourism development area to be an industrial township, and may by notification, declare the Tourism development area to be a notified area: Provided that, the State Government may, while declaring the notified area, include or exclude the village site area (gamtal) of a Village Panchayat or Municipal area.”

[…]

Section 38 says, “(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in this Act or in any other law for the time being in force, no person shall have any right or any claim over any land which has been acquired by the State Government or by any Government agency prior to coming into force of this Act within the Tourism Development area and had vested in it, (2) It shall be competent for the State Government to remove any person from the land referred to in sub-section (1).”

This provision which attempts to convert a Schedule V and PESA area into an industrial township is prima facie ab-initio void.

The Act does not stop here. In section 3 (3), the Act says:

“The State Government may also, by notification in the Official Gazette, extend the Tourism development area as and when it deems fit. …. Section 4 (2) states that “The headquarters of the SOU Tourism Authority shall be at Kevadia, District Narmada: Provided that the State Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, specify any other place as the headquarters of the SOU Tourism Authority. … Section (3) (a) says, “The SOU Tourism Authority shall consist of 22 members from different authorities, out of that President, the District Panchayat will be locally elected. Final authority lies with state government.”

Plenty of amenities, but not for Adivasis

Under section 2(a), the Act defines ‘amenities’ as “basic and essential services including but not limited to roads, bridges, bypasses and underpasses, drainage, water supply, power supply and electrical installations, collection-treatment- discharge and disposal of institutional and township waste, health, education, transport, disaster management, parks, green areas, gas pipeline, entertainment, hospitality, recreation, industry, townships and institutional areas and other facilities of conveniences and such other services as the SOUADTG Authority may specify;”. This makes it abundantly clear that everything in the Act is for tourism and nothing for the local tribals(Adivasis).

Under section 9. (xii), the Act promises

“sufficient civic amenities including drainage and services including hospitals and medical services, schools, fire services, public parks, markets and shopping places, play grounds, entertainment areas and disposal of waste.”

At (xiii), the Act talks of

“sustainable arrangements for providing and maintaining the highest standards in civic amenities such as water supply, sewerage, power supply, transportation, communication, infrastructure and services particularly for cleanliness, aesthetics, health, hygiene, etc.”

Phrases such as ‘sufficient civic amenities’ and ‘highest standards in civic amenities’, again raise the question: for whom and at whose cost? Obviously these amenities are definitely and exclusively meant for tourists and the tourism industry and will be at the cost of the local tribals. At no point does the Act state that the so-called highest standards in civic amenities and other facilities will also be available to the local tribals or ‘occupiers’.

Restrictions introduced on Adivasis

Not only is the welfare of the tribals (Adivasis) absent as a concern, Chapter VI (Control, Regulation and Development in Tourism Development Area) the Act actually places restrictions on them. Section 11 (1) states that,

“On or after the date on which the SOU Tourism Authority is constituted, no person shall carry on any development in any building or in or over any land, within the limits of the said Tourism development area without the permission in writing of the SOU Tourism Authority.”

Section 13 (1 ) states,

“Any person not being the Central Government or a State Government, intending to retain any use of building or work constructed or carried out on any land, or to continue any use of any particular land, before the date on which a final development plan comes into force, which is not in conformity with the provisions of the regulations or the final development plan, shall make an application in writing to the SOU Tourism Authority for permission to retain or continue such use, containing such particulars and accompanied by such documents and such fees as may be determined by regulations, within six months from the date on which the final development plan in respect of such Tourism development area comes into force.”

Who monitors the actions of the SOUTA? Are they allowed a free hand in this area?

The words “shall make an application in writing to the SOU Tourism Authority for permission to retain or continue such use” clearly imply that the local tribals have to renew or reregister everything, even their existence, via a written application – as if they are outsiders.

State authority can enter any home at will

The Act states under section 42. (1) states:

“For the discharge of duties and functions cast under this Act any person authorized by SOU Tourism Authority or any other person authorized by the State Government or any authority shall be authorized to enter into or upon any land or building with or without assistance: Provided that –

(i) no such entry shall be made except between the hours of sunrise and sunset or without giving its occupier at least 24 hours’ notice in writing of the intention to enter in the case of any building used as a dwelling house or in the land wherein such building exists;

(ii) sufficient opportunity shall be given to enable a woman to withdraw from such land or building;

(iii) due regard shall always be had to the social and religious usages of the occupants of the land or building entered.

(2) Any person who obstructs the entry of a person empowered or authorised under this section to enter into or upon any land or building shall on conviction, be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year or with fine which may extend to fifty thousand rupees or with both.”

What emerges from the above provisions is a draconian law that empowers the state to act against its most vulnerable citizens, the local tribals of the area.

Curbs even on the right to protest?

The Act tries to redefine the people’s fundamental rights to protest by stating under section 26:

“Notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force, or any instrument, contract or usage or any order, judgment or decree of any court, no person, company, association or firm or any other body shall cause any nuisance within the Tourism development area.”

Further under section 27 (1),

“The Prescribed Authority, either on its own motion or upon a complaint received or upon reference made to him, may, by an order in writing and without giving any prior notice, prohibit any nuisance being caused or prevent any such activity, process, operation being carried out, if in his opinion, the same has damaged or deteriorated or is likely to damage or affect adversely to tourism potentiality of the Tourism development area, and pass such interim orders as it deems fit.”

The immunity provided to the authorities to terrorise the local inhabitants is made clear in section 51:

“No suit, prosecution or other legal proceedings shall lie against the SOU Tourism Authority, other Government companies or any of their committees, members, officers and employees for anything which is in good faith done or intended to be done in pursuance of the provisions of this Act or any rules or regulations made thereunder.”

It should be unambiguously apparent from the above discussion that the state government and, by direct and indirect implication, the Central government, have armed themselves with extraordinary powers in order to ‘develop’ this area exclusively for tourism without caring for the adverse human and environmental consequences and with no provision whatever for the preservation of the rights of the indigenous people.

Indeed, a careful scrutiny of the Act and its directives reveals irresponsible short-sightedness on the part of the state and Central governments. It needs to be recognised that the local tribals are the true nurturers of the forests and their allied ecosystems. These ecosystems, by virtue of their natural processes, automatically form the basis of any recreational activity for the enjoyment and de-stressing of the urban populace.

It should also be noted that we are following in the very footsteps of the so-called “developed” world where the native populations were systematically displaced, leading to the many environmental revolutions of the 1960s by various peoples’ movements. The West learnt from its mistakes and constituted various Natural Conservation Areas. However, much of the indigenous knowledge and cultural base was already lost. It is pertinent to ask where we are headed with our development model. Can we not learn from the pattern of past mistakes?

The statue of Sardar Patel, its associated ‘projects’ and the Act have today become de facto symbols of resource destruction, river lynching and subjugation of the indigenous population – who have come to live in fear of the state and its violence. All this in the name of “Unity”.

Rohit Prajapati and Krishnakant and Gujarat-based activists.