Kodia village, Bhopal: A heated argument had broken out among half-a-dozen farmers gathered near a dimly-lit dairy shop in Kodia village in Bhopal district, 30 km west of the city. “Bharatiya Janata Party ka kuchh vote abki baar katega humare kshetra me, kisan naraz hain (The BJP will lose some of its votes in our region this time, the farmers are angry),” said Vikram Gor, 40, one of the farmers, shouting to be heard above the din.

“Modiji said he would double our incomes…where are the achhe din [good days]?” asks Hridesh Gaur (centre), 34, a farmer from Bhopal district. This traditional BJP stronghold is also angry with the Congress for not keeping its promise of waiving all loans of up to Rs 2 lakh.

Divided into two tehsils (administrative blocks)–Huzur and Berasia–Bhopal with 1.9 million electors will go to polls on May 12, 2019 in India’s ongoing general elections. Winning with 51% votes in the 2009 general elections and 63% votes in 2014, the constituency has been a stronghold of the BJP.

But, in our travels here–a state whose agriculture sector has recorded the fastest annual growth in the eight years to 2015 (10.9%)–we found farmers unhappy with the BJP. It is widely believed that farmer fury had voted the party out of the state assembly in 2018, after 15 years in power.

“Modiji said that he would double our incomes but in his later years in power he even stopped the bonus we used to get for wheat,” said Hridesh Gaur, a 34-year-old farmer. “Kahan hain acche din (where are the good days the party promised)?” he added referring to one of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s slogans. Gaur was referring to the fact that after coming to power in 2014, the Modi government had stopped states from giving bonuses over the minimum support price (MSP) reasoning that this distorted the market, affected cultivation patterns and increased the subsidy burden.

Farmers in Kodia were unhappy that in the ongoing election frenzy, the central and state governments had forgotten their problems–securing an MSP for all major crops, and bringing in measures to deal with poor irrigation infrastructure, rising farm debts and drought.

But, the Congress, which has been in power in the state for four months, has not managed to impress Kodia’s voters either.

“The Congress is no better,” said Gaur. “Farmers voted for them in the state election because they promised loan waivers for farm debts of up to Rs 2 lakh. I also have a debt of Rs 2 lakh but only Rs 35,000 got waived.” The bank is refusing to give him an all-clear certificate till it gets the loan money it waived from the government.

About 41% of India’s rural voters are worried about irrigating their farms, 39% about loan availability and 39% about higher price realisation for farm products, according to a March 2019 survey by Association for Democratic Reforms, a Delhi-based advocacy.

Drought has dried up water sources, worsened agri distress

Most public tube-wells and taps had run dry in Kodia. Only 15-20 private ones, about 500-ft deep, had any water left and the families that owned these were sharing the water with the rest of the village. The extraction of water through tube-wells is banned but the people of Kodia have no other option.

“If you go around the village at around 6 in the morning, you can see lines of women and children standing in different alleys in front of various houses, waiting for their turn to fill buckets,” Gor said.

Bhopal is among the 36 of Madhya Pradesh’s 52 districts to face a drought in 2019. Most parts of the state experienced 20-50% deficient rainfall over two consecutive years. In the ongoing drought that has gripped 42% of India’s land area, Madhya Pradesh is among the worst-hit, IndiaSpend reported on April 3, 2019. This has exacerbated the farm distress that the state is already reeling under.

About 40 rivers that provide water to 4,000 villages in the 36 drought-hit districts have dried up and the micro-watershed management system is in a complete disarray. More than 21.29 million hectares of the catchment area of these rivers–69% of state’s total area–is parched along nearly a distance of 2.19 million km, according to a report by the panchayat and rural development department of the state, IANS reported on March 16, 2019.

One of the primary reasons for this drought is insufficient and irregular rainfall.

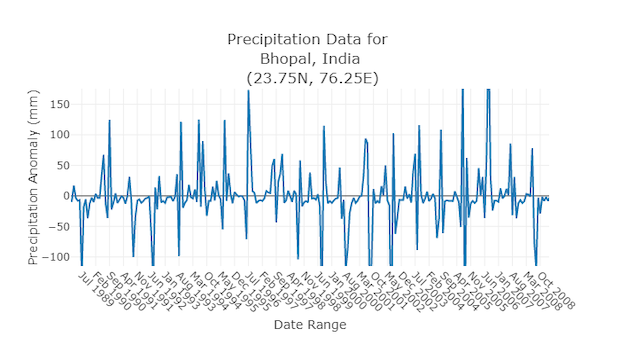

Rainfall in Bhopal has not only been deficient since 2017, it has also become erratic over 20 years to 2018. The south-west monsoon months–June to September–have been experiencing increasingly long dry spells coupled with events of heavy rainfall, according to NOAH, an application that tracks rainfall and surface water changes using satellite data.

Source:NOAH, an application that tracks rainfall and surface water changes using satellite data.

| Rainfall Data For Bhopal District Over Five Years to 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | ||||||||||||

| Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | Rainfall | %DEP | |

| 2014 | 58.5 | 396 | 47.9 | 584 | 3.5 | -46 | 3.3 | 32 | 7.6 | -22 | 23.2 | -79 | 427.1 | 26 | 165.9 | -53 | 109 | -43 | 12.4 | -63 | 0 | -100 | 22.3 | 135 |

| 2015 | 40.1 | 240 | 0 | -100 | 45.5 | 600 | 1.6 | -36 | 13.1 | 35 | 166.7 | 49 | 473.8 | 40 | 315.2 | -11 | 42.6 | -78 | 3.2 | -91 | 0 | -100 | 0 | -100 |

| 2016 | 21 | 78 | 0.4 | -94 | 5.4 | -17 | 0 | -100 | 9 | -7 | 150.1 | 34 | 660.5 | 95 | 531.3 | 49 | 122.2 | -36 | 76.9 | 128 | 0 | -100 | 0 | -100 |

| 2017 | 3.4 | -71 | 2.8 | -60 | 1 | -85 | 0 | -100 | 17.6 | 81 | 102.9 | -8 | 334.5 | -1 | 126.2 | -65 | 217.4 | 13 | 0 | -100 | 0 | -100 | 0.2 | -98 |

| 2018 | 0 | -100 | 13.3 | 90 | 1.5 | -77 | 3.7 | 48 | 0.5 | -95 | 113.5 | 2 | 352.9 | 4 | 264.5 | -26 | 75.3 | -61 | 12.9 | -62 | 0 | -100 | 0 | -100 |

Source: India Meteorology Department

Not just Bhopal, most of Madhya Pradesh has experienced a significant decline in monsoon rains over 62 years, from 1951 to 2013. This is attributed to climate change, according to a 2016 study by Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad.

The state receives 90% of its rainfall during monsoon months when reservoirs and underground aquifers are recharged. This water is used to irrigate winter crops. But due to increasing events of heavy rainfall, the water runs off instead of percolating into the ground.

In central India, the frequency of days with heavy rainfall (at least 100 mm/day) increased from 45 to 65 days per year over 50 years to 2000, while the frequency of extreme rainfall events (at least 150 mm rainfall/day) has doubled from 9 to 18 days per year during this period, as per a 2013 study by the Bhopal-based Indian Institute of Forest Management (IIFM).

Agri distress worsens

Erratic rainfalls in the last 15 years have caused up to a 60% decrease in crop yields in the eastern part of Madhya Pradesh, with about 90% of the region being rain-fed, said the IIFM study linking the rainfall variability to the crop productivity.

Like the rest of the state, for farmers in Bhopal–where 42% of net sown area is rainfed–sparse rainfall means loss of produce and income.

“I usually get 15-16 quintal of wheat from an acre, but in the last cycle, I only got 6-7 quintal (down by 56%) due to lack of water,” said Gor. “There was very little rain in 2018 and by the time we started sowing wheat in November, there was very little water in the bore wells. We could only irrigate the wheat crop once after sowing it.” Wheat normally needs three rounds of irrigation.

Usually farmers in MP sow only two crops, kharif (monsoon crops) and rabi (winter crops). But some also plant zayad (pre-monsoon crops). About 10-15% of farmers in Kodia used to cultivate pre-monsoon vegetables but the drought has made that impossible, we were told.

“The administration here has not done anything to manage the drought yet,” said Gor.

Farmers here have also been demanding canals for irrigation. “But, neither the state nor the central government heeded us,” said Hridesh Gaur. “A farmer cannot be successful if he depends only on underground water.”

If a borewell fails, a farmer needs Rs 2 lakh to get it repaired and so he takes another loan and this raises farming costs again while crops continue to fetch meager rates at the market.

A fractured farm economy with about 46% households indebted poses a challenge to the growth of the state that depends on agriculture for 30% of its income. As many as 1,321 farmers committed suicide in MP in 2016, the highest since 2013, according to the government data presented in Lok Sabha on March 20, 2018. While farm suicides dropped by 10% elsewhere in the country in the two years to 2016, Madhya Pradesh saw a 21% jump, IndiaSpend reported on November 30, 2018.

In the last decade, the state has also seen many farm protests. The last big agitation, in 2017 in Mandsaur, a district located 300 km north-west of Bhopal, had turned violent after six farmers were killed as police fired on them. The main demand of farmers was a higher MSP, a demand that is now common nationwide.

MSP: the crux of the farm crisis

“Why can’t our MSP be ensured?” asked Anmol Mewarha, 59. “Iss karz se hi kisaan marta hai (this debt kills farmers).”

With the cost of production rising, farming is no longer a profitable enterprise. The government has declared the MSP for wheat (Rs 1,840/quintal) and soybean (Rs 3,399/quintal), Kodia’s main crops. “But we rarely get to sell our produce at the MSP,” Mewarha complained.

Madhya Pradesh contributes 19% to the national output of wheat and is its second largest producer, after Uttar Pradesh. It is the largest producer of soyabean, producing 31% of the national output.

“It seems like we are punished for one thing that we are supposed to do… produce more,” said Gor.

Why then is the state still reeling under an agricultural crisis? To understand the problem, Mewarha helped IndiaSpend chart the cost and market rate for both the crops for an entire crop cycle.

Wheat needs three months to ripen, he explained, and a profit of Rs 2,000 per hectare means an earning of just Rs 600 per month to spend on his family of four. This is 50% lower than what he used to get a decade ago. “Input cost has doubled in the last 9-10 years, halving our profit because the government did not increase the MSP in the same ratio,” he said.

As per Mewarha’s calculation, soybean farmers bear a 30% loss per hectare due to low market rates for the produce. “A farm labourer who earns Rs 200 per day makes more money,” he said. “Anaaj bech lo, phir karz chadha do, aur paisa khatam (Sell your produce, pay back the debt and the money is over.)”

‘Why not implement existing MSP?’

The story of MP’s farmers is the story of India’s farmers in an era of record harvests. India grew more foodgrain in 2017 than ever before, and the government’s agriculture budget rose 111% over four years to 2017-18, as IndiaSpend reported in January 2018. Yet prices crashed, unpaid agricultural loans grew 20% over the year to 2017, and 600 million Indians who depend on farming struggled to get by.

The average monthly income of an agricultural household in MP is Rs 6,210, which lags behind the national average of Rs 6,426 (July 2012-June 2013), Mint reported in June 2017.

To provide farmers MSP for their crops, the state needs to strictly implement the existing regulation in the market act, GS Kaushal, former director of the state’s agriculture department, told IndiaSpend. “MP’s mandi act clearly says that if the produce passes the quality test, it cannot be bought below MSP,” said Kaushal. “Why does the government not enforce this?”

Families engaged in agriculture have been losing their purchasing power and faulty government policies are compounding the crisis, Kaushal said. “Why should the government promote subsidised imports of agricultural commodities available in the country?” he asked.

Not only does the agriculture market need a policy shake-up but the government also needs to increase storage facilities and re-survey the cost of cultivation to revise the MSP for different crops, Kaushal said.

Flagship schemes of BJP and Congress fail to impress farmers

After being defeated in assembly elections in three states–MP, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh–the BJP government at the Centre, in its last budget, launched a scheme to pay farmers with less than 2 hectares of land, a sum of Rs 6,000 every year. The move was seen to counter the loan waivers offered by the Congress during its campaign for the assembly elections. But, both, the Congress and the BJP have failed to impress the farmers of Kodia.

Om Prakash, 57, is a farmer who also runs a small grocery shop to pay for his family’s daily expenses. “Modiji is paying us Rs 6,000 a year but that isn’t enough to even buy clothes for my family of five,” he said. “Has he never visited a farmer’s house to understand his expenses? I am not going to vote for the BJP this time.”

“Modiji is paying us Rs 6,000 a year. This amount can’t even buy clothes for my family of five. Has he never visited a farmer’s house?” Om Prakash (white shirt), like most farmers in Kodia village in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, is upset that all farmer issues have been forgotten in election frenzy.

His neighbour, and a farmer, Badri Prasad countered him. “It is true that the BJP has not done a lot, but most of the good initiatives in the state happened during Shivraj Singh Chouhan’s 15-year long tenure,” he said.

It was Singh’s government which allowed farmers to sell their wheat at cooperative societies, which are closer than the agriculture markets. “Before that farmers had to wait in long queues for days at markets to sell their wheat,” said Prasad.

The farmers we spoke to were not happy with the Congress regime’s implementation of its promise to waive farm loans upto Rs 2 lakh within 10 days of coming to power. “It has been six months, small loans, say of Rs 30,000-Rs 40,000, have been waived but what about the big loans?” Prasad asked. “It is better that Modi be given another chance.”

The Congress government’s farm loan waiver is said to have benefitted 3.4 million farmers who had taken loans of up to Rs 2 lakh from national and co-operative banks till March 31, 2018.

“I will not vote for Congress until my last breath,” said Mohan Lal, 58, a farmer whose kurta and dhoti have turned yellow with time and overuse. “When Digvijay Singh (Congress candidate from Bhopal in current elections) was chief minister, he took seven acres of my land and distributed it into scheduled caste under a scheme. I am only left with one acre now.”

The BJP government had given every household an LPG gas connection to cook under the Ujjwala scheme, he pointed out. But his 50-year-old wife continues to cook in mud stoves. “The gas is costly we use it only on special occasions,” said Mohan.

(Tripathi is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend