In the decades post-Independence, a young independent India made remarkable strides in both pure and applied sciences, transforming sectors like agriculture, food technology, and space science. This is equally true of basic sciences, humanities, creative literature and social sciences, disciplines in which rationality, free thinking, and scientific temperament collectively created an ecosystem and enabling atmosphere for research output in every field of knowledge.

This progress is evidenced by India’s status as one of the largest producers of fruits, vegetables, and dairy, aided by the veterinary sciences and animal husbandry. In 1974, India conducted its first nuclear test (Operation Smiling Buddha) in Pokhran, moved towards enhancing its energy production, and by 1975, it had developed its own satellite, Aryabhata. Initially dependent on imports such as US wheat and tinned milk from the Netherlands, India quickly achieved food self-sufficiency by invoking “Green Revolution” which was followed by “White Revolution” through Amul Cooperative Society, and “Poultry Revolution”. From the 1980s, various Technology Missions helped achieve such goals. The flagship programmes of the Indian government to improve the nutritional status of children and reduce incidence of malnutrition through the Integrated Child Development Scheme and Mid-Day Meal Scheme are exemplary, not to say of other pro-poor welfare schemes and rural development. Even, the first wave of Indian professionals to work abroad included graduates from the world-class technical institutions established in the post-independence era.

However, despite these noteworthy foundational accomplishments, the quality of research and innovation in India has stagnated over the past two to three decades. This is alarming, particularly because other nations—including the countries that lagged far behind India just 40–50 years ago—have rapidly advanced. With a population of 1.4 billion, a growing focus on Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, and a shortage of job opportunities, India is today at a crucial juncture. Addressing these challenges requires a unified effort from the government, the academia-intelligentsia, and industry. Through appropriate policies, resources, and a shift in research culture, India will acquire the potential to regain its place as a global leader in research and innovation.

Nonetheless, for action after introspection, the relevant data pertaining to our research performance are quite troubling. Some of these may be elaborated below:

- Citation Impact: According to the “Scimago Journal & Country Rank” (SJR), which assesses academic impact globally, India ranks outside the top 100 countries for citations per document across all subject areas (https://www.scimagojr.com/countryrank.php), including Sciences, Life Sciences, Engineering, Humanities and Social Sciences. Indian research averages only 12.7 citations per document, significantly trailing countries like the United States, Canada, and scores of countries in Europe, which exceed 25-30 citations per paper. Researchers from several Asian countries, including Saudi Arabia (17.6), Nepal (15.2), Oman (15.1), and Bangladesh (14.5), also surpass India in citation impact. While India performs slightly better in Engineering and Sciences, its ranking is notably lower in Arts and Humanities.

- H-Index Ranking: India is not among the top 20 nations in terms of the h-index across all subject areas, which measures scientific productivity and citation impact. Although India has largest population, the number of citable documents produced (2.7 million) is significantly lower than that of countries like the USA (14 million) and China (10 million). Particularly the emphasis is quite less in publishing in high ranked journals in the fields of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities.

- Top-tier [Q1] Journal Publications: High-ranking institutions are often evaluated by their contributions to Q1 (top quartile) journals, representing the top 25% in each field. India’s highest-ranking institutions—the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS, New Delhi)—are positioned only at 1346 and 1360 globally.

(https://www.scimagoir.com/rankings.php?sector=Higher+educ.&country=IND).

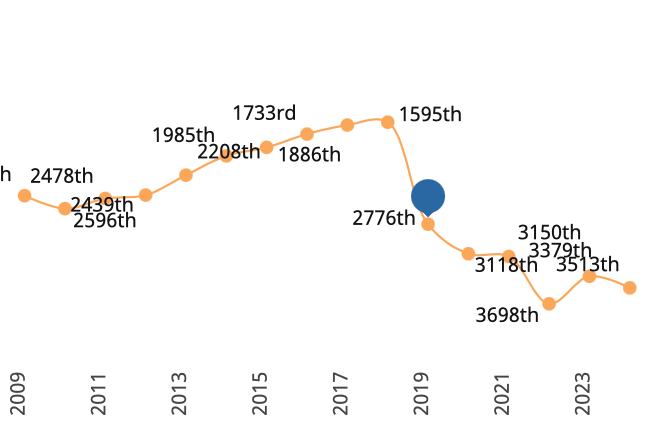

For example, if one looks(Fig.1) at the declining publications in the journals of repute by the researchers at a highest funded, historic and a largest residential public university, the Aligarh Muslim University(AMU), then the scenario gets quite depressing, hence, a matter of great concern.

Fig.1: The research ranking of the Aligarh Muslim University refers to the volume, impact and quality of the institution’s research output. On the X-axis is year and Y-axis is global ranking.

Source: https://www.scimagoir.com/institution.php?idp=3231#google_vignette

- Global Innovation Index (GII): In the 2024 Global Innovation Index, India ranked 39th out of 160 economies (https://www.wipo.int/gii-ranking/en/india), indicating room for improvement in innovation capacity.

- Patent Generation: India granted only 0.03 million patents compared to 0.8 million in China and 0.3 million in the United States, illustrating a significant lag in protecting and commercializing intellectual property.

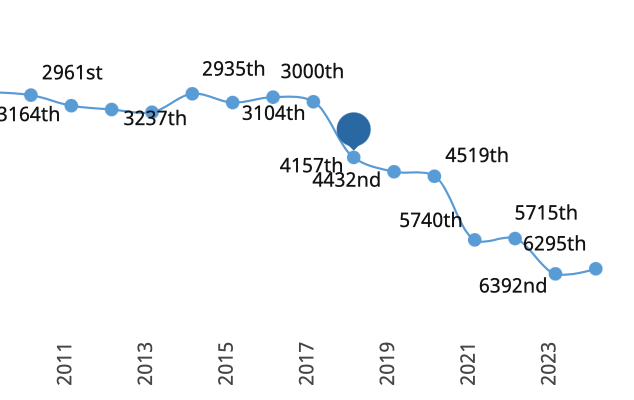

For instance, if one looks (Fig.2) at the declining number of innovation ranking of AMU, the issue is again quite alarming.

Fig.2: The innovation ranking of the Aligarh Muslim University, which is calculated on the number of patent applications of the institution and the citations that its research output receives from patents. On the X-axis is year and on Y-axis is innovation ranking.

Source: https://www.scimagoir.com/institution.php?idp=3231#google_vignette

Root causes of this decline in our academia:

In our estimation, several factors contribute to India’s declining research quality and innovation output, such as:

- Evaluation standards focused on quantity: Academic institutions often emphasise the quantity of publications rather than quality. Shifting focus to high-impact research would reward rigorous, ethical research practices and enhance India’s international credibility. Prioritising quality over quantity attracts international collaborations and investment, creating an environment that promotes scientific integrity. Strict standards for recruitment, based purely on merit and publication in reputable journals and books, are sometimes compromised. Promotions to higher-level positions are not stringently monitored by institutions. People who publish in journals or magazines that are not even indexed by the h-index are often promoted readily. Publications with publishers that lack rigorous standards and anonymous peer review are accepted without scrutiny. Furthermore, student feedback in both letter and spirit is frequently ignored in universities and colleges.

The primary focus of faculty members in academic institutions therefore should remain on their core responsibilities of research and teaching. These activities not only contribute to personal academic growth but also significantly enhance the institution’s reputation and academic excellence. Engaging in meaningful research furthers the frontiers of knowledge, while effective teaching shapes the next generation of scholars and professionals.

- Insufficient R&D investment: India’s research and development expenditure is less than 0.7% of GDP, placing it outside the top 150 countries for R&D investment.

In contrast, the developed nations such as the USA (3.5%), Germany (3.1%), and Israel (5.5%) allocate much more for R&D. Even some developing countries, such as Cuba (11.5%) and Oman (6.8%), outspend India in this area. Thus, adequate funding is essential for basic research, which forms the foundation for applied sciences and technology development. This is why it is paramount to strengthen basic research laboratories.

- Inadequate focus on basic sciences: Without robust fundamental research in the basic sciences, the applied researches cannot progress. Industries often hesitate to fund basic research due to its indirect, long-term returns. However, government’s substantial financial support is essential here. Breakthroughs in medical technologies, like X-rays, MRI, PET scans, and radiotherapy were made possible by early investments in basic sciences. To foster innovation, India must prioritize basic research alongside applied sciences.

- Urgent need for financial support in colleges and public universities: To ensure the quality of education in colleges and public universities, it is imperative to prioritise financial support for critical infrastructure. Laboratory courses, which are central to hands-on learning, have been significantly affected by the lack of equipment. Decades ago, these institutions boasted better-equipped laboratories, allowing students to explore and innovate. However, over the past four to five decades, there has been a marked deterioration in these facilities, leaving many students unable to gain practical skills in key areas. Equally concerning is the condition of libraries, which are fundamental to fostering independent learning and research. Many institutions struggle to maintain updated collections of books, journals, and other resources due to insufficient funding. Addressing this issue is vital to bridging the gap between students’ learning potential and the resources available to them. Moreover, the shortage of faculty members poses a significant challenge. In many colleges, the faculty strength is considerably below the required levels, compromising the quality of instruction and mentorship. This situation directly impacts the ability of institutions to maintain academic rigor and to support students effectively.

- Limited Institutional Autonomy: Granting universities and research institutions more academic and administrative autonomy would enable them to respond quickly to emerging research needs. Accountability frameworks should be in place to uphold ethical standards, ensuring that institutions remain credible and internationally competitive.

A Curious Case of the AMU: Nepotism and Inbreeding Corroding Meritocracy

Let the foregoing discussion be illustrated with the instance of the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), a significantly funded, large residential university. There appears to be an increasing trend where around 20% to 25% of the AMU teachers perennially prioritise grabbing administrative positions including those positions traditionally designated only for the non-teaching staff. Extracting this undue benefit has gone up to the extent that even the positions of the statutory officers are filled in on ad hoc basis, in flagrant violation of the UGC rules, and even on illegal basis, as revealed in a recent information obtained through the RTI Act 2005. Some of these “Non-Teaching Professors” have delayed obtaining their PhD degree and have been happily continuing in the administrative positions.

This sorry state of affairs is owing to the fact that, this is often to gain associated “material” benefits over and above salary, including, institutional vehicles with drivers and security personnel serving as domestic servants of the teacher-officers, at the expense of the University exchequer. Many of these teachers have been holding such positions for an outrageously long time, for the last many years, uninterruptedly. Their poor CVs, with no significant/respectable research output, adversely affect the ranking of the University.

AMU, unlike all other central universities (CUs), has got an overwhelming hegemony of the internal teachers inside its Executive Council which also empanels its Vice Chancellors. In the last two empanelment (2017 and 2023), only internal teachers have succeeded in becoming AMU-VCs. This aggravates the practice of nepotism and inbreeding in recruitments and promotions, at the expense of meritocracy. This has had an additional corrosive effect on research output of AMU.

Having developed deeply entrenched, strong clout, they incapacitate successive VCs and create layers of red-tapism just in order to harass and humiliate academically accomplished teachers. The overall atmosphere and ecosystem of the University is made anti-academic. The academically productive ones are harassed by delaying/denying promotions to them, as the VCs are perennially under the pressure of this internal hegemony. Internal teachers becoming as VCs of AMU do not have the independence (or guts) to act against these interests with whom they have been living, working and will continue to live with them even after completing their tenures as VC!

Non-teaching positions are typically designed to support administrative and operational functions, ensuring the smooth running of the University, and are best suited for personnel with expertise in these areas. Unfortunately, these roles are increasingly being used for personal advantage, benefiting the teachers themselves, their family members, and their friends. At some places, the prolonged (rather than a brief tenure) occupation of such positions has led to the formation of regional and sub-regional layers of hegemony and therefore unbridled nepotism in enrolments, recruitments and promotions. These maladies are actively destroying the academic ethos of teaching and research.

Needless to say, this shift in focus dilutes the academic mission and also undermines the intended division of responsibilities within the universities.

By prioritising research and teaching over such non-academic roles, faculty members can better align with the university’s objectives of fostering an environment of intellectual rigour and student development. Clear policies and guidelines can further help delineate responsibilities, ensuring that non-teaching roles are fulfilled efficiently by the appropriate staff while enabling faculty members to concentrate on their academic and scholarly pursuits. This alignment benefits not only the institution but also the broader academic community.

Just as in AMU, other universities too must have got their own general as well as more specific problems. Insiders of those universities also need to expose their endemic problems on these counts.

By tackling the abovementioned critical challenges head-on, India can revitalise its research ecosystem and emerge as a dominant force in the global knowledge economy. Is the government really prepared to listen?

Achieving this vision calls for a concerted effort: substantial government funding, a robust fellowship system based purely on merit, and strong collaboration between academia and industry. With strategic investments, a transformative approach to academic assessment, and greater institutional autonomy, India is poised not only to advance ground-breaking research and innovation but also to become a global beacon of knowledge and progress.

Sajjad Athar is a Professor of Physics at AMU, Aligarh, a renowned name in nuclear physics, a co-author with the Nobel Laureate Prof. Takaki Kajita who tweets @Mohamma84063425; Mohammad Sajjad is a Professor of History at AMU who tweets @sajjadhist.