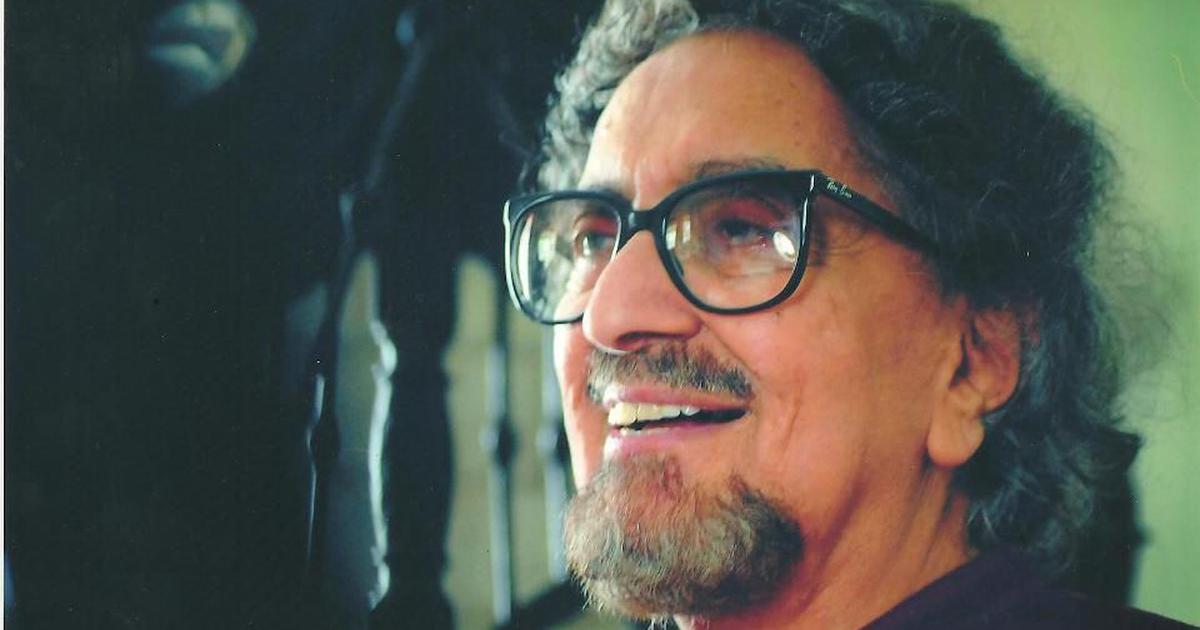

He gave generously of his creativity and wealth, and always stood on the side of truth and justice.

It was 1987 and I was a reporter at The Indian Express in Mumbai. One day, I was called to the 15th floor of the Express Towers. The icon of the advertising world, Alyque Padamsee, had penned a note for me, requesting a meeting. Exhilarated, I went up in the lift. I remember noticing a vast fish tank that encompassed a whole wall as I waited.

Ushered in to meet the man himself, I was thrilled to see clippings of three of my stories, one published that very day, pinned to his board, encircled in red. I had reported from drought-stricken southern Rajasthan; a tragic case of a distraught farmer who had killed his two children before taking his own life had sensationally helped put the focus on the looming threats from shrinking groundwater levels. Alyque and his team swung into action. Public service advertising was his creation. With an advertisement of strong visuals of rigid and parched earth and pithy text, Lintas, his advertising firm, raised not just monies (Rs 12 lakh, a princely sum at the time) for the affected farmers, but also awareness about what caused repeated bouts of drought.

Thus began our close association, and a lasting bond of affection, love and respect. Alyque was the ultimate philanthropist, giving generously of his creativity and wealth to victims of tragedies, natural and man-made. Whether it was the Latur earthquake of 1993, the Gujarat earthquake of 2001, the Orissa cyclone of 1999, the communal violence in Bombay in 1992-’93 or in Gujarat in 2002, Alyque put his money where his wonderfully loud mouth and particular nasal voice always was. When we formed the Citizens for Justice and Peace in April 2002, he was a natural choice for founder trustee with Vijay Tendulkar, our founding president. He was active until almost the end; only in recent months had he found it difficult to attend our meetings.

Harnessing the power of mass media and social communication for a greater purpose: to spread the message of justice, truth and secularism. How do we make peace and secularism sexy ideas? These were the preoccupations of Alyque, a man who had made the Liril Fresh ad with a sprightly girl, bathing under a Khandala waterfall, what wistful dreams were once made of.

Just as he would have wanted

I will always regret not seeing him one last time. To be told by him, repeatedly, how and where to stress on communication and the message. How to make harmony as appealing as hate, violence and gore. To never give up on mass media.

It was at around 10.45 am on Saturday that I heard about his demise. I spoke to each member of his family in turn: his wife Sharon, daughter Raell and son Quasar. The call to his former partner Dolly is waiting to happen. Shazahn, his young daughter who was his “best buddy” and took him dancing and to movies, is heartbroken. Each one of this crazy and wonderful caboodle was in a car cavalcade driving down from the hospital when we exchanged words, tears and memories. There will be a cremation on Sunday, then the immersion of his ashes at Awaas in Alibag, Maharashtra. Thereafter, in larger-than-life Alyque style, a rock star concert. Just what he would have wanted and what he always looked out for. Generous with the young, encouraging of the well-meaning, active round the clock in his own way to help make this world an ingenuously better place to be in.

His mother, a redoubtable Khoja from Gujarat, was his lasting inspiration. Strong and single, she inspired what always remained in Alyque a deep respect for the individual, courage and stark fortitude. His first wife Pearl, who is no more with us, remained a friend even after they had parted ways.

I am set to do a live interview about the Zakia Jafri case relating to the Gujarat riots of 2002. It is coming up in the Supreme Court on Monday, and I know Alyque will be out there, watching. Worried for me, for us, worried about whether justice will ever be completely done.

Adieu, Alyque.

Teesta Setalvad is a civil rights activist.

This article was first published on Scroll