With a New Education Policy in the works, and with several criticisms of its draft version published, including on our site, ICF spoke to Anjali Noronha, one of the founding members of Eklavya, a non-profit NGO based in Madhya Pradesh which has participated in government-school curriculum and textbook reform, improvement in pedagogy, and teacher education for over three decades. The interview focused on long-standing problems in school education in India, especially in the Hindi-speaking states.

© Jacob Lawrence, 'Play', Harriet Tubman series, 1939-40 / Art in Embassies

In your view, what important issues are left unstated in the discussion about school education in India?

A discourse on the social aspects of education is missing. What actually prevents children from learning? This question is nowhere to be heard in the discourse on education. Instead, the reasons usually cited are that teachers aren’t on time or are absent, do not teach, are given other work and have no time to teach – and that if they were diligent the children would learn.

We need to recognise that the culture of literacy or numeracy is a culture of the elite. In our homes, a very young child will be shown a book and given affection if they read it, making reading an enjoyable, emotional activity. In schools, dalit kids will be pushed aside, and if there are books available they won’t be given any. Social exclusion results in exclusion from access to learning resources, and is one of the most important reasons for children not learning. But in all the discussion about learning levels and exam performance, no one points out the social and emotional aspects of reading, and the grave deprivations faced by children who are neglected or deliberately kept out. Instead, discussion centres on the pedagogy of literacy – whether to teach the alphabet or sight-words, or to adopt a whole language approach, even though Devanagari and related Indian scripts are quite phonetic, so the problems of acquiring English literacy are not at play here.

There are non-exam, self-paced, multi-age group learning pedagogies which have shown that children from deprived families are able to remain in school and, if given specific attention, also show improvement in learning. Out-of-school support for such first-generation learners also proves extremely helpful. Through somewhat different pedagogies Digantar, Rajasthan and Rural Schools of Rishi Valley have demonstrated in their schools that children of all backgrounds can learn together in a system where the focus is on each individual child. Similarly, Eklavya’s Shiksha Protsahan Kendras have shown that, in a similar multi-age group learning environment, out-of-school support helps sustain children through the primary level right up to high school, significantly more than in schools where such support is not available.

But far from making special efforts to create an inclusive, well-functioning school system, successive governments seem to be withdrawing altogether from their constitutional duty to ensure universal education. This is evident from the large numbers of government schools being closed down across the country, and the rapidly increasing privatisation of both school and teacher education.

Any developing society has to be built on the back of a robust public school system, whereas in the last two decades or more, there has been a lot of pressure to privatise schools and universities. Government high school results in Delhi were much better than those of private schools on the average. When this was mentioned to government officials in Chhattisgarh, they said this was also the case in that state. Yet they did not publicise it. Given the fact – there is ample evidence to show this – that today it is government schools which cater to the poorest and most marginalised, this is indeed a feat to be celebrated. However, both the government and the media, particularly the prime-time media, chose to ignore it, focusing instead on ill-performing schools.

They are creating a mindset: anyone with a regular income wants to send their children to private schools. Data too is not presented and used properly. Some studies give separate data for private and government schools and argue that private schools perform better; whereas when they control for students' socioeconomic backgrounds, it is often government schools which actually do better. Yet the separately tabulated data is disseminated, as in the case of the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), even as their own studies showing a different picture are not publicised.

A chronic problem, particularly in the northern states, is the frequent changes in pedagogy, without a rigorous understanding of any pedagogy at all. Multi-age and multi-grade pedagogy has been tried on a large scale in both Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, and has been shown to be better than textbook-based pedagogies. There were problems in upscaling these fast, problems which needed to be addressed. Instead, these methods were suddenly stopped.

Not dealing with issues of social exclusion, poor implementation of policy, and frequent changes in textbooks and pedagogy tends to put our system in a worse situation. Finland, often talked about as an educational leader, has worked on its education bit by bit in a coherent direction, resolving problems as they come up. Yet we tend to follow America, which despite good facilities has steadily declined in the quality of elementary education, as well as equity in education. "High stakes" do not yield good results, but we go in for more and more testing of students, instead of addressing the problems we already know we have.

What is the importance given to teachers, to educating and remunerating them, in our system?

Poor teacher education is at the core of the bad state of affairs in India. There is an assumption in the education community here that you don’t need to know much to become a teacher. If you compare the situation to professional courses like law, medicine or engineering, these have four-year courses at minimum, compared to three years for the humanities – and only two years of post-school education are required of primary school teachers.

Delhi University offers a four-year Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) course. The Justice Verma Commission on Teacher Education (2012) proposed a two-year B.Ed. across the country: since these were court orders state governments have to implement the report's recommendations, but most are doing so in a mechanical manner, by spreading out the content of a one-year course over two. At present the course is not planned to span two years.

There is no separate Teacher Educator cadre in most states. In Madhya Pradesh all schoolteachers are first recruited on contract, for a period of two years, at salaries ranging from Rs. 5000–7000 per month. Fifteen years ago they were recruited at Rs. 500 per month! In Delhi, there is a cadre of public schoolteachers who are paid at the Sixth Pay Commission salary levels (2008), about Rs. 30,000 per month. Owing to these pay scales, the cutoffs for admission to Diploma of Education (D.Ed.) courses are quite high in the southern states and in Delhi, where additionally graduates of the four-year Bachelor of Elementary Education (B.El.Ed.) are in high demand.

The commission entitled them to good pay, but the teachers on grade slowly retired and all new teachers were recruited on contract. These contracts are negating the increase in the value of work done by schoolteachers. A few years ago, the Madhya Pradesh government instituted a process for bringing contract teachers into the cadre, after three years' teaching. But there are still thousands of vacant posts. The situation in the south is much better.

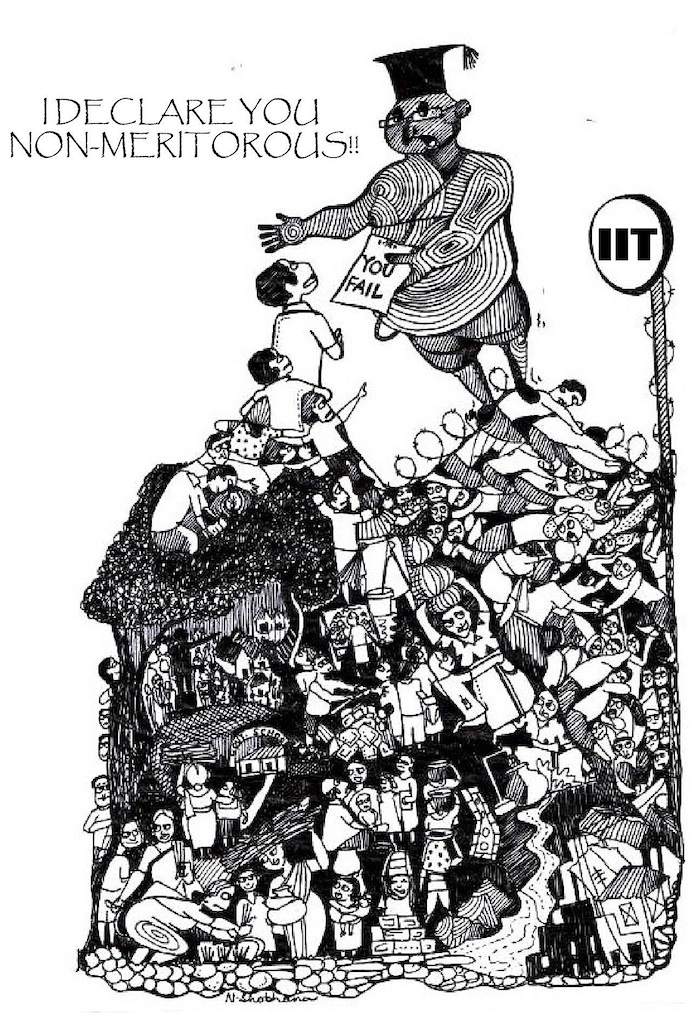

© Nidhin Shobhana / Round Table India

With the government itself such a reluctant employer of schoolteachers, have there been attempts to improve teacher education?

The National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education (NCFTE, 2009-10), which I was involved in drafting, tried to take the policy decision that for elementary schoolteachers they would move to a four-year course. But there is usually a huge gap between policy and programme, and a programme to take us in that direction has not materialised. One of the main reasons for this gap is that in order to change to a four year course, a much larger faculty is required, of a higher quality. That’s why the Justice Verma Commission was set up by the Supreme Court, followed by several committees for implementing its recommendations. It has already been six years since the Right to Education (RTE) Act came into force; it was supposed to be implemented in three.

Overhauling the two-year B.Ed. course was also meant to be a time-bound process. The earlier, archaic, hundred-year-old Bachelor of Teaching/ B.Ed. course dealt separately with theory and teaching, pedagogy and lesson plans, etc. Now a much more holistic one has been made. Since education is a concurrent subject the states are responsible for implementing education policy. The overhauled course takes a lot from the four-year B.El.Ed. course, for instance in school immersion/ apprenticeship programmes. For 40–60 days a year, trainee teachers spend the whole day at school, participating in all classroom or school activities – and they must observe children as part of their training.

Training in teaching, that is, rather than just the subject matter?

Both. Content and pedagogy are integrally linked. The pedagogy of science has to be very different from the pedagogy of language, even if both follow the principles of participatory learning. Language learning may be participatory without the need for physical learning materials, whereas this is not possible in the context of good science teaching and learning. Generic pedagogy like the Herbatian five steps does not end up being very meaningful.

There is also a lot of diversity in Indian schools, which does lead to discrimination against underprivileged children, girls, etc. The ‘School and Society’ (शाला और समुदाय) paper in the new two-year D.Ed. course recognises different communities and ways of learning, and assigns teachers child observation tasks in the community. The idea is to initiate some process of transformation of the teacher, rather than just the student. The ‘Childhood and Development’ paper talks about different childhoods, not just one – this was a significant move. And the language papers talk about multilingualism rather than one pure language.

You mentioned the gap between policy and practice. Has there been encouraging, concrete action by states or the centre in recent years?

In the years following the NCFTE, the D.Ed. curriculum and syllabus revised according to the new guidelines, which mandated looking at children’s backgrounds, instituting robust pedagogy courses and an intensive school internship as part of the course. And, for the first time, reading materials were written with care for students. This was done in Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Bihar, taking cognisance of the fact that because no proper reading materials are available in the vernacular for student teachers, to pass exams they take recourse to cheap guides and keys (कुंजीs) that flood the market. So this has been a crucial step in improving teacher education, done for the first time. Additionally, faculty of the District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) which run the D.Ed. courses have been oriented in the teaching of the new course.

It takes decades to reform a section of the school system. This was realised by Professor J.P. Naik, one of India's foremost educationists, way back in the sixties when he said such reform takes 25 years. It took Finland 25 years to top the world. But here, in India, every two or three years there is a new policy or programme to move us in a different direction from the previous one.

Despite this, if you look at the situation at the village level, where government-school teachers have no support, and have to face criticism and indignity at various forums… They are not only coping in a situation where most of us would fail, but are doing tremendous work educating scores of first-generation learners from extremely deprived communities. Instead of lauding their efforts, the government, the media and society continue to run them down in public. It has been found across the board that when you control for students' socioeconomic backgrounds, government schools do as well as private schools, or better. Yet, as mentioned, studies including ASER tabulate data so as to show that private school students perform better. This is falsely assumed to be a consequence of private schools being better, whereas it is actually a product of the cultural capital of the class that comes to private schools – the economically and socially better-off. It is important to guard against such false notions.

What changes do we see as a public school system gives way to one dominated by private, for-profit schools?

The private school system has no accountability. A private school could be progressive or regressive, good or bad. The provision in the RTE Act mandating a 25% quota in private schools for children from "economically weaker sections" (EWS) has emptied out a lot of government schools. Schools are organised in clusters – in Bhopal a cluster may have 8-10 government primary and 80-100 private primary schools. These latter are relatively small but still, each 25% means a huge drop in public school enrolment, which in Bhopal has declined by as much as 60% in the last ten years.

As government schools empty out due to the twin effect of propaganda that they do not perform well and the RTE provision of 25% admission in private schools, the logic for closing them down strengthens. Earlier, teachers would go from house to house to get students to come to their school. Now, they have to go to private schools to ensure that 25% EWS students are enrolled there.

Far from private schools becoming inclusive, children from EWS here face exclusion, comments about their clothes or tiffin, and bullying. The teachers have not been oriented in how to deal with this. Some schools even have separate sections for the 25% EWS children. Parents in turn have to bear the cost of books, uniforms and additional materials. Private schools in district towns like Hoshangabad are sending buses to the interiors to bring in students from the villages. This system of busing ensures that the rural elite send their children out of the village to be educated – this is generating and increasing polarisation in society.

Earlier we all had friends from different communities and were exposed to different things. In private schools there are hardly any dalit students (though the situation may have changed since the RTE 25% quota). Whereas in government schools, less than 5% of the students are from the "general" category; and these are usually girls. This is leading to segregation and is fertile ground for breeding biases about the other – the rich about the poor, the poor about the rich. This will be one of the serious fallouts of a privatised system.

Moreover, a private commericialised school system is accountable only to profitability, not to the social aims of society, not to what makes a "good human being". This will be the other major fallout.

© Arpita Singh, 'Bhishma' / Invaluable

© Arpita Singh, 'Munna Apa's Garden' / Art Market Monitor

Courtesy: indianculturalforum.in