The Article 370 that gave the erstwhile state special status has been deemed by legal experts as a constitutional and legal bridge between India and the state of Jammu and Kashmir after the latter’s accession to India under peculiar circumstances. While the apex court’s adjudication on the matter is awaited, it would be worthwhile to look at the history of Article 370 and some debates around it.

“Soon after independence all these states acceded to one or the other dominion as per the arrangement except Hyderabad, Junagadh and Kashmir.”

Historical Context

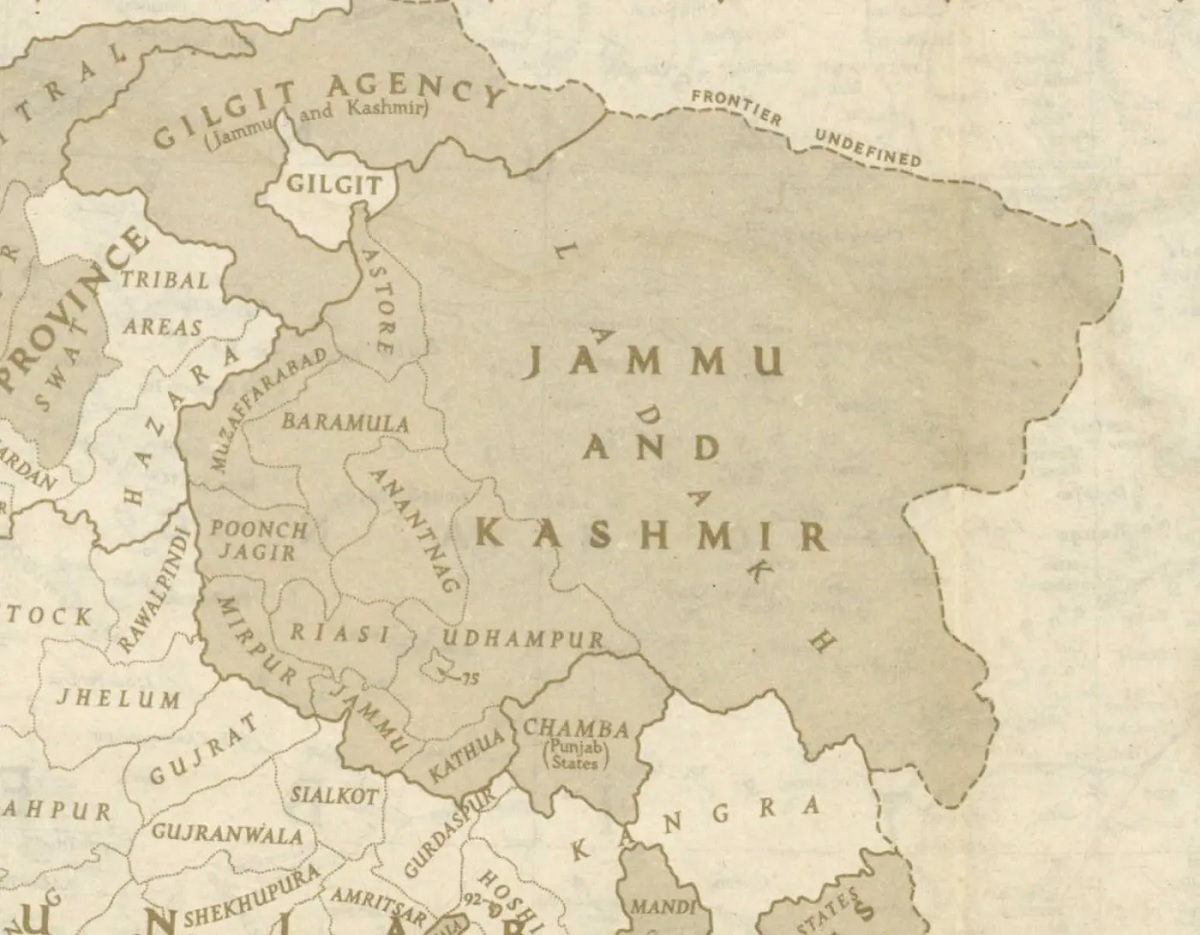

Jammu and Kashmir was one of the 562 States under the suzerainty of British Crown after the independence of India and its partition on the basis of religion which was left to decide its future. All these states automatically regained full sovereign and independent status, free to join either of the two dominions or remain independent. The underlying principle for the choice before the states was the will of the people and the geographical location, even though these principles were not binding on the princely states.

According to legal expert, Faizan Mustafa, technically, the Instrument of Accession was like a treaty between two sovereign countries that had decided to work together. The maxim of pacta sunt servanda in international law, which governs contracts or treaties between states, asks that promises must be honoured.

The last Viceroy of the British empire, Lord Mountbatten put forward before the rulers two documents – the Instrument of Accession and a Standstill Agreement, for the continuance for the time being of agreements and arrangements in matters of common concern between the states and the dominion of India.

Mountbatten told the princes on July 25 1947 that the “Indian independence Act releases the States from all their obligations and the states have complete freedom technically and legally they are independent.” He added that the states are theoretically free to link their future with whichever they may care “but when I say they are at liberty to link up with either of the two dominions may I point out that there are certain geographical compulsions which cannot be avoided.” He elaborated you “cannot run away from the dominion government which is your neighbour any more than you can run away from the subject for who’s welfare you are responsible.”[i]

Soon after independence all these states acceded to one or the other dominion as per the arrangement except Hyderabad, Junagadh and Kashmir.

Junagadh and J&K

A.G. Noorani in his book ‘The Kashmir dispute – 1947 to 2012’ makes a comparison of Jammu and Kashmir which was a Muslim majority State ruled by a Hindu ruler and Junagadh, a Hindu majority ruled by a Muslim ruler. India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had objected to Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan on grounds that the population of Junagadh was 80% Hindu and batted for a referendum under impartial auspices. The princely state was surrounded on all of its land borders by India, with an outlet onto the Arabian sea. Its ruler, Nawab Muhammad Mahabat Khanji argued that Junagadh was linked to Pakistan by sea against the advice of Mountbatten.

The Indian position was that Junagadh had acceded to Pakistan ignoring geographical considerations and the principle of religion or the exercise of the will of the people. This became the basis of Indian army’s military intervention in Junagadh to wrest it of Pakistan’s and the Muslim ruler’s control. This, however, was followed by a hasty referendum in February 1948 and by an almost unanimous vote the people showed their preference for India. Many scholars, however, have observed that India annexed Junagadh by force and laid down the international opinion on the principle of accession – geographical contiguity to the dominion and the demographics. The mobilisation of Indian defence forces in the lead up to the accession of Junagadh in November 1947 and the management of violence directed at Junagadh’s Muslims afterwards are an instance of the forcible incorporation of Indian princely states and Indian Muslims into the reconstructed post-colonial state.[ii]

Mountbatten and Ayyangar both agreed that the issue of geographical contiguity had no legal standing and that Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan was strictly and legally correct. But Sardar Patel demanded that the matter of the state’s accession should be decided by its people instead of the ruler.

“The state of Jammu and Kashmir had concluded a Standstill Agreement with the government of Pakistan in regard to the maintenance of the existing arrangement in respect of posts and telegraphs etc and thus it was open to Kashmir to exceed to either of the two dominions or remain independent.”

Hyderabad, ruled by a Muslim leader presiding over a Hindu majority and with no geographical link to Pakistan, met a similar fate. Stephen P. Cohen writes, “The vision of a future India and Pakistan rubbed against the ambitions of some of the princes, with the result that the rush to force them to join one or the other ignited several significant conflicts.” Although, technically, the decision to accede was in the hands of the ruler, not the ruled, India used force to incorporate Hyderabad and Junagadh, he writes.[iii]

Scholars are divided on the question of whether the decision was to be made by the rulers or the ruled. The will of the latter, a principally more moral option, could be asserted only through a referendum. Whatever the morality of the question, India could not have applied two yardsticks for the different princely states awaiting a decision on their future.

Besides, if the principle of geographical contiguity and demographics was valid for Junagadh, could a different yardstick be applied to Kashmir. The state of Jammu and Kashmir had concluded a Standstill Agreement with the government of Pakistan in regard to the maintenance of the existing arrangement in respect of posts and telegraphs etc and thus it was open to Kashmir to exceed to either of the two dominions or remain independent.

“This period of indecisiveness coincided with several other almost simultaneous events – the communal troubles in Jammu following the movement of refugees from West Punjab into Jammu, the Poonch revolt against the Maharaja and the armed tribals entering the state with the connivance and support of the Pakistan authorities, forcing the Maharaja to send a desperate distress appeal for help to the government of India.”

Period of indecisiveness

Mahatma Gandhi on a visit to the state in August 1947 said that the will of the Kashmiris should decide the fate of Jammu and Kashmir and added that the sooner this was done the better he also hoped that the question would be decided between the two dominions, the Maharaja and the Kashmiris, elaborating that “if the four could come to a joint decision then much trouble would be saved.”

The Maharaja who wanted to save and safeguard his princely privileges was uncomfortable in signing an accession either with India, looking towards a democratic and anti-feudal future, or with Pakistan, with its Muslim majority. Sheikh Abdullah, who was released from jail in September 1947, also made his preference publicly known towards independence, warning that that if the state declares accession to India or Pakistan, he would raise the banner of revolt.

This period of indecisiveness coincided with several other almost simultaneous events – the communal troubles in Jammu following the movement of refugees from West Punjab into Jammu, the Poonch revolt against the Maharaja and the armed tribals entering the state with the connivance and support of the Pakistan authorities, forcing the Maharaja to send a desperate distress appeal for help to the government of India. The exact chronology of events is a matter of speculation and academic debate, in the light of fuzzy evidence but what is significant is that all of these factors were co-related and had a direct or indirect bearing on the other, engendering tensions and creating divisive fault lines that would become part and parcel of the region’s destiny.

Instrument of Accession

After the armed tribals from North West Frontier province entered Kashmir, Indian minister V.P. Menon flew to Srinagar where he met the Maharaja on October 26, 1947 and both left Srinagar for Delhi where Menon reported to the defense committee that the only basis of sending troops into an independent country had to be accession. He also opined that in view of the composition of the population, accession should be conditional on the will of the people being ascertained after the raiders have been driven out of the state and law and order have been restored. After this meeting it was decided that the accession of Jammu and Kashmir should be accepted subject to the proviso that a plebiscite would be held in the state when the law and order situation allowed this decision. This had the fullest support of Sheikh Abdullah, noted Menon.

The circumstances of accession were peculiar. The Hindu Maharaja of the Muslim majority state had initially wanted to stay independent. He signed the Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947, after Pashtun tribals aided by Pakistan invaded Jammu and Kashmir, and India agreed to help only on the condition of accession. The Schedule appended to the Instrument of Accession clearly gave the Indian Parliament power to legislate for Jammu and Kashmir on only three subjects – defence, external affairs and communications.

Faizan Mustafa writes, In Clause 5 of the Instrument of Accession, Hari Singh said that the terms of “my Instrument of Accession cannot be varied by any amendment of the Act or of The Indian Independence Act unless such amendment is accepted by me by an Instrument supplementary to this Instrument”. In Clause 7, he said: “Nothing in this Instrument shall be deemed to commit me in any way to acceptance of any future Constitution of India or to fetter my discretion to enter into arrangements with the Government of India under any such future Constitution.”

Article 370 was a constitutional recognition of the conditions mentioned in the Instrument of Accession, and reflected the contractual rights and obligations of the two parties.

In his reply on October 27 1947, Lord Mountbatten responded, “it is my government’s wish that as soon as law and order have been restored in Kashmir and her soil cleared of the invaders, the question of the state’s accession should be settled by a reference to the people.”

Particularities of J&K accession

Noorani notes that Jammu and Kashmir accession was the only unique instance of being accompanied by a letter which the Maharaja wrote to Lord Mountbatten. The significant details of the letter state that “Jammu and Kashmir is contiguous to both the dominions it has vital economic and cultural links with both of them”. It also points out its international strategic significance with proximity to Soviet republic and China. He mentioned that “under the standstill agreement the Pakistan government was operating Posts and Telegraph system in the state” and that “Pakistan had tried to put pressure on the state to accede culminating in the communal tribal raids”. It added, “with the conditions obtaining at present in my state and the great emergency of the situation as it exists, I have no option but to ask for help from the Indian dominion. Naturally they cannot send the help asked for by me without my state acceding to the dominion of India I have accordingly decided to do so and I attach the Instrument of Accession for acceptance by your government the other alternative is to leave my state and my people to free booters.”

In his reply on October 27 1947, Lord Mountbatten responded, “it is my government’s wish that as soon as law and order have been restored in Kashmir and her soil cleared of the invaders, the question of the state’s accession should be settled by a reference to the people.”

The accession thus was not permanent and irrevocable. It had to be settled by a referendum which was principally agreed to by the Indian government before and after the dispute went to United Nations. New Delhi took the case to the UN resulting in a UN resolution to resolve the dispute through a referendum after demilitarization from both sides, beginning with withdrawal of Pakistan Army from the state. Both India and Pakistan occupy the two parts of J&K and have kept the political dispute alive, giving rise to insurgency since 1989.

Article 370

On October 17, 1949, Article 370 was included in India’s Constitution by the Constituent Assembly after it was moved for consideration as Article 306A. In defence of the special status for Jammu and Kashmir during the Indian Constituent Assembly proceedings, N. Gopalaswamy Ayyangar had pointed out that the condition of the state was “not ripe for full integration” and reasoned that a significant degree of autonomy had to be given within the constitutional structure of the Indian Union. He said, “The effect of this Article is that the Jammu and Kashmir State which is now a part of India, will be a unit of the future federal Republic of India.”[iv]

Ayyangar said, “we have also agreed that the will of the people through the instrument of the Constituent Assembly will determine the constitution of the state as well as the sphere of union jurisdiction over the state. At present, the legislature which was known as the Praja Sabha in the state is dead. but neither the legislature nor the constituent assembly can be convoked or can function until complete peace comes to prevail in that state. We have therefore to deal with the government of the state which, as represented in its council of ministers, reflects the opinion of the largest political party in the state. Till a Constituent Assembly comes into being only an interim arrangement is possible and not an arrangement which could at once be brought into line with the arrangements existing in the case of other states now if you remember the viewpoints that I have mentioned, it is an inevitable conclusion that, at the present moment, we could establish only an interim system Article 306A is an attempt to establish such a system.”[v]

It is also a relevant piece of history that Article 370 (then Article 306A) was passed unanimously with only one dissenter. He was interestingly not the Hindu right-wing ideologue, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, but Maulana Hasrat Mohani, founder of Communist Party of India. The latter’s objection was not to the grant of special status to Kashmir but he was seeking similar models of autonomy for all other states of India in pursuance of his concept of federalism.[vi]

Promise of referendum

The commitments to Kashmir’s special status and promise of a referendum were reiterated several times, thereafter. At a press conference on June 11, 1951, Nehru said, “we have made it perfectly clear that the constituent assembly of Kashmir was not meant and is not meant to come in the way of any decision which might flow ultimately from the security council’s decisions” in response to a question.

At another press conference in New Delhi on June 21, 1952 Nehru said, “when Security Council asked us about it we made it clear to the council again that the Kashmir government had every right to have a constituent assembly to frame the internal constitution but so far as we were concerned we would not be bound by their decision on the question before the Security Council”.

Subsequently in a speech delivered by Nehru in the Lok Sabha on 26th June 1952, Nehru said, “Let us suppose there was a proper plebiscite there and the people of Kashmir said ‘we do not want to be with India’. Well, we are committed to it. We would accept it. It might pain us but we would not send an army against them. We might accept that, however, much hurt we might feel about it and we would change our constitution about it.” In another important speech in the parliament on 7th August 1952, Nehru again said, “We do not want to win people against their will and with the help of armed force and if the people of Jammu and Kashmir state so wish it to part company from us, they can go their way and we shall go our way. We want no forced marriages no forced unions like this.” [vii]

Legal scholar, Faizan Mustafa, writes, “Some critics of Article 370 have argued that Kashmir joined India in 1947 without any conditions, and Article 370 unnecessarily gave it special status. However, the drafting of the Constitution ended on November 26, 1949 — Article 370 had been included before the Constitution was adopted.”

Conciliation and resolution, however, always remained peppered with mutual suspicions. Attempts to resolve Kashmir dispute came a cropper right in the beginning. New Delhi and Pakistan issued a joint communique on August 21,1953 to reiterate their commitment to holding a plebiscite on Kashmir and decided that the plebiscite administrator should be appointed by April 1954. Both the prime ministers of India and Pakistan took keen interests, following this significant communique with further correspondence and were nearing an agreement both with regard to a regional plebiscite and the choice of the plebiscite administration to be selected from an Asian State but signs of discord soon appeared.

Apparently, Nehru developed cold feet on the news of massive US aid for Pakistan and negotiations for a military pact between Pakistan and United States, invoking fears in New Delhi that United States would interfere in the Kashmir question. Nehru conveyed his apprehensions to Pakistan but even after the US-Pakistan pact was signed on May 15, 1954 Nehru said India still stands by her international commitments on the Kashmir issue and “will implement them at the appropriate time.”

These statements pointing to India’s reiteration of commitment towards referendum and settlement of Kashmir dispute are indications of the legality of Kashmir dispute. Kashmir’s accession to India and its consequent constitutional status were thus only interim arrangements. Article 370 was temporary only till the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir could modify, retain or reject it. The Constituent Assembly of Kashmir before adjourning sine die in 1957 decided to retain it.

Legal scholar, Faizan Mustafa, writes, “Some critics of Article 370 have argued that Kashmir joined India in 1947 without any conditions, and Article 370 unnecessarily gave it special status. However, the drafting of the Constitution ended on November 26, 1949 — Article 370 had been included before the Constitution was adopted.”

Inevitability of special status and anxieties

The need to recognize the special status in view of the nature of partition and the history of Jammu and Kashmir coupled with the unique circumstances of its accession continued to be felt even as New Delhi remained uneasy with respect to the state’s Muslim majority status in conjunction with the hostile journey between India and Pakistan. The anxieties of the Muslims living within were reciprocal like Newton’s third law of motion; and both these eventually began to shape the aspirations and desires of the minorities of Jammu and Kashmir. The Indian state was not only mindful of both. It played up the latter to counter the former. But before that happened, Nehru was guided by the moral and democratic question.

Abdullah, who had played a key role in Kashmir’s conditional accession with India had expressed fears about the future of a Muslim majority region in India, thus, earning Nehru’s mistrust. When the Sheikh brought plebiscite demand out of the bag, it was a red herring for Nehru.

According to A.G. Noorani, the 1952 Delhi Agreement, between then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Kashmiri leader Shiekh Mohammad Abdullah, has explicitly given the solemn pledge to protect identity and culture of Kashmiri people by preventing outsiders to own land in the disputed region as well as to protect its demographic character in the Hindu majority India, an identical reason that compelled Hindu ruler to enact the law in 1923.

“So, the present government of Kashmir is very anxious to preserve that right because they are afraid, and I think rightly afraid, that Kashmir would be overrun by people whose sole qualification might be the possession of too much money and nothing else, who might buy up, and get the delectable places. So, we agreed and noted this down,” Nehru told Indian parliament in 1952.

Abdullah, who had played a key role in Kashmir’s conditional accession with India had expressed fears about the future of a Muslim majority region in India, thus, earning Nehru’s mistrust. When the Sheikh brought plebiscite demand out of the bag, it was a red herring for Nehru.

Erosion of Article 370

These mutual anxieties and insecurities prompted New Delhi to manipulate Jammu and Kashmir’s politics and continuously make attempts to erode its special status and hollow out Article 370 after Sheikh’s deposition and arrest. The Presidential Order of 1954 and subsequent orders allowed the extension of almost the entire Indian Constitution to Jammu and Kashmir.

94 out of 97 entries in the Union List were applicable to Jammu and Kashmir, 260 out of the 395 Articles of the Constitution as well as 7 out of the 12 Schedules of the Indian Constitution were extended to the state before the Article 370 was completely decimated on August 5, 2019. Article 35 A, which defined the classes of persons who are, or shall be, permanent residents of the state of Jammu and Kashmir; or conferring on such permanent residents any special rights like employment in the state government and acquisition of immovable property, came into being through one such presidential order but only to lend clarity to the definition of Jammu and Kashmir’s ‘permanent resident’.

Eventually, the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir enacted the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir, which accepted the state’s position as an integral part of India while retaining the special status provided under Article 370. It also barred on the future Legislative Assembly from interfering with the constitutional relationship between the state and the Union. The full and final seal to Article 370 was stamped making it irrevocable.

Was Article 370 temporary or irrevocable

A common myth with respect to Article 370 is that it was temporary and thus could have been revoked any time. According to the constitution, Article 370 was a temporary provision in the Constitution to govern the state’s relationship with the rest of the Union but only till such time as the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir met to determine the exact nature of the relationship. Eventually, the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir enacted the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir, which accepted the state’s position as an integral part of India while retaining the special status provided under Article 370. It also barred on the future Legislative Assembly from interfering with the constitutional relationship between the state and the Union. The full and final seal to Article 370 was stamped making it irrevocable.

The Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly adopted a Constitution on November 17, 1956, to come into force on January 26, 1957. Its Article 3 stated that “the State of Jammu and Kashmir is and shall be an integral part of the Union of India.” Article 4 lays down that the territory of the State shall comprise of the territories which on the 15th of August 1947 were under the sovereignty or suzerainty of the ruler of the State. It was also decided that the legislative assembly would consist of 100 members and 25 seats were to be left vacant “until the area of the State under the occupation of Pakistan ceases to be occupied…..”

Several court rulings in recent years are illustrative of the fact. In 2016, the Supreme Court acknowledged the special status of J&K and reaffirmed that Article 370 was not temporary. The court observed that Article 370 cannot be repealed without the concurrence of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. In 2017, Delhi High Court rejected a petition that argued that Article 370 was temporary, and that its continuation was a fraud on the Constitution. The same year, the apex court said that due to historical reasons, Jammu and Kashmir had a special status. In April 2018, the Supreme Court said that the word “temporary” in the headnote notwithstanding, Article 370 was not temporary.

The verdicts prior to these were also on similar lines. In the famous 1968 case of Sampat Prakash versus State of Jammu and Kashmir, the apex court decided that Article 370 could be invoked even after the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. “Article 370 has never ceased to be operative,” the Supreme Court laid down.

August 5, 2019 J&K Reorganisation Act

The watering down of Article 370, re-orientation of Jammu and Kashmir state, its division and creation of two separate union territories on August 5, 2019 thus brings into focus the legality of such a move, as is argued by constitutional jurists. The manner in which this was done raises questions of constitutional, moral and democratic propriety.

On August 5, 2019, the constitutional changes to Jammu and Kashmir were brought by a Presidential Order 272, a statutory resolution in the parliament that recommended the president to de-operationalise Article 370 and the J&K Reorganisation Act that broke up the state into Union Territories of Ladakh, without a legislature, and Jammu and Kashmir, with an emasculated legislature, under two all-powerful Lieutenant Governors, enabling Central Government to directly rule the state.

According to this presidential order, the concurrence of the government of the state of Jammu and Kashmir has been taken. However, Jammu and Kashmir was under President’s Rule and thus the consent taken was that of the Governor, virtually a representative of the central government. This was a case of the Centre taking its own consent to amend the constitution. This was ultra vires of the constitutional provision of Article 370, according to whose Clause 3 the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly of J&K was imperative to make any amendments. However, the Constituent Assembly of J&K ceased functioning in 1957.

The President invoked modification powers under Article 370 by issuing the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019 to substitute the Constituent Assembly of the state with the Legislative Assembly of the state, thereby removing the constitutional requirement to convene a newly elected Constituent Assembly to determine the future of Article 370. Since President’s rule under Article 356 was in operation in Jammu and Kashmir, the government argued that Parliament can act as the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir while recommending the abrogation of Article 370.

The Presidential order adds a sub-clause to Article 376, replacing the terms “Constituent assembly of Jammu and Kashmir” to mean “legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir” and “government of Jammu and Kashmir” to mean “governor of Jammu and Kashmir acting on the aid and advice of the council of ministers”. The Presidential order also requires the concurrence of the government of the state. But since the state at that time was under presidential rule, the consent of the Governor, an appointee of the Centre, is meaningless as it virtually means that the government is taking its own consent to radically alter the constitution.

Legal experts on Article 370 revocation

“Even if the words can be replaced, it breaches the spirit of the provision. The Constituent assembly’s recommendation is essentially to include the key stakeholder’s voice while making substantial changes to Article 370. The Centre cannot do so unilaterally,” according to senior advocate Raju Ramachandran.

When a State is under President’s rule, Article 356 (1) (b) empowers the President to vest the powers of the Legislative Assembly of the state with the Parliament. But these powers are an interim arrangement for the enactment of laws till a new Legislative Assembly is elected, so that the state is not adversely affected due to the absence of an Assembly. The consent required under Article 370 (3) is not routine legislative power. It is a constituent power which determines the nature of the constitutional relationship between Jammu and Kashmir and the rest of India.

Faizan Mustafa argues that the presidential orders were issued against the letter and spirit of the Instrument of Accession and that the August 5, 2019 were “a negation of the constitutional compact” signed between India and the J&K Maharaja. Jammu and Kashmir had acceded to India in 1947, only on three subjects – defence, foreign affairs and communication.

What the Central Government did was to use Article 367 which provides various guidelines about how the Constitution may be interpreted to remove the necessity of J&K constituent Assembly’s consent from Clause 3 of Article 370. This is the first time that Article 370 was used to amend Article 367 eventually to amend the Article 370 itself.

Gautam Bhatia, clarifies, “370(1)(d) makes it even clearer where it refers to the “other provisions” of the Constitution that may be altered by Presidential Order (and this is how the present Presidential Order is different from previous ones, such as those that introduced Article 35A). Article 370 itself, therefore, cannot be amended by a Presidential Order.”

Thus, the interpretation of the special provision was altered to dilute the very provision and wipe it out without fulfilling the requirements under Clause 3 of Article 370. What the BJP government did by bringing a presidential order, a resolution and a bill to reorganize the state in the parliament on August 5 is to invoke modification powers under Article 370 to substitute the Constituent Assembly of the state with the Legislative Assembly of the state, thereby removing the constitutional requirement to convene a newly elected Constituent Assembly to determine the future of Article 370.

Faizan Mustafa argues that the presidential orders were issued against the letter and spirit of the Instrument of Accession and that the August 5, 2019 were “a negation of the constitutional compact” signed between India and the J&K Maharaja. Jammu and Kashmir had acceded to India in 1947, only on three subjects – defence, foreign affairs and communication.

Article 370 limited the application of the provisions of the Indian Constitution to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Under Article 370(1)(d), constitutional provisions could be applied to the state from time to time, as modified by the President through a Presidential Order, and upon the concurrence of the state government (this was the basis for the controversial Article 35A, for example). Gautam Bhatia writes, “Perhaps the most important part of 370 was the proviso to clause 3. Clause 3 itself authorised the President to pass an order removing or modifying parts of Article 370.”

The proviso stated that: Provided that the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly of the State referred to in clause (2) shall be necessary before the President issues such a notification.

So, effectively, in view of dissolution of the legislative assembly in Jammu and Kashmir which is under president’s rule, the government arrogated the right of the assembly to the Parliament, where the BJP enjoys absolute majority. The August 5 changes were based on this flawed premise of deeming the J&K Governor as the legal and constitutional substitute for Constituent Assembly or even legislative assembly.

Secondly, presidential rule is temporary and therefore changes of permanent character like constitutional amendments without the existence of the elected legislative assembly amounts to a constitutional fraud.

In an interview, senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan said, “This order seeks to supersede a constitution—Jammu and Kashmir has a constitution devised by a constituent assembly. Therefore, Article 370 came into being [in 1950] while Jammu and Kashmir had not established its constitution. Article 370 was transitional only to the extent, and until, Jammu and Kashmir constitution came into place……… Jammu and Kashmir constitution [formed] by an independent constituent assembly is a fact—it is a legal fact, a spatial fact and a temporal fact. You cannot abolish it, as simple as that—it does not grow out of the [The presidential] order.”

Similar view was shared by legal expert, A.G. Noorani, who has authored a book on Article 370, among several other books on Kashmir. “The Indian government’s power to abrogate Article 370 had vanished after the dissolution of Kashmir’s Constituent Assembly in 1956. Article 370 was meant to express the identity of Jammu and Kashmir, because of the special circumstances, in which it acceded to India. And that identity is sought to be destroyed. It got a special status because of the historical circumstances,” he explained.

Emphasising that the Indian parliament was not empowered to either amend or delete the provision, Noorani said, “For this, the approval of the J&K State’s Constituent Assembly was necessary. Any concurrence of the state government is always subject to the elected assembly’s final approval. When the state is under governor’s rule or president’s rule, neither can accord that concurrence,” he said. “The Centre cannot acquire concurrence from its own handpicked appointee (Governor) removable at will,” he wrote in an article and termed the action by Indian government “illegal and against the spirit of its own constitution”.

The constituent assembly of Jammu and Kashmir did not exist on August 5, 2019. The legislative assembly was dissolved. No consultations were ever held with any of the stakeholders turning this exercise into something that invokes a sense of humiliation among its citizens. Not only were the people’s special status rights snatched, they were also divided and granted a status that was much lower than the status of a fully integrated state in this forced integration process as per the J&K Re-Organisation Act that was subsequently passed on August 9, 2019.

There are four grounds to believe this assertion to be reasonably true. 1) The Instrument of Accession with Jammu and Kashmir was finalized with the provision of Article 370 in the Indian Constitution. 2) The Bill was not referred by the President to the state assembly 3) Governor is neither an equivalent of constituent assembly or legislative assembly and thus cannot arrogate on himself the legislative powers of the state government. 4) The illegitimacy of using Article 370 to amend Article 367 which in turn is used to completely make Article 370 redundant.

Senior Congress leader, parliamentarian and lawyer, Manish Tewari, in an interview with Kashmir Times, said that the grounds for bringing down Article 370 was laid down in December 2018 when the presidential proclamation, announcing president’s rule in Jammu and Kashmir, suspended proviso 2 of Article 3 of the Indian Constitution. He said that this was unique and removed the mandatory provision of consultation with the state legislature before re-organisation of any state.

J&K residents stripped of agency

Article 370 was amended, not revoked, neutered and made inoperative. By virtue of this dilution, all the Presidential Orders since 1950, including Article 35A that defined who a permanent resident is, protected the Muslim majority status of the state and protected the exclusive land rights of all its citizens, stood invalidated, and Indian constitution was extended to state of Jammu and Kashmir, truncated and demoted into two union territories in toto.

The constituent assembly of Jammu and Kashmir did not exist on August 5, 2019. The legislative assembly was dissolved. No consultations were ever held with any of the stakeholders turning this exercise into something that invokes a sense of humiliation among its citizens. Not only were the people’s special status rights snatched, they were also divided and granted a status that was much lower than the status of a fully integrated state in this forced integration process as per the J&K Re-Organisation Act that was subsequently passed on August 9, 2019.

Effectively, the people of Jammu and Kashmir had not been consulted about their future by circumventing the constitutional provisions. Before the union home minister moved the legislation, 13-14 million people whose fate Parliament was deciding were virtually put under a siege with imposition of Section 144, excessive militarization and internet ban. With sweeping arrests and detentions, civil rights kept under prolonged suspension, what was abrogated were the last remaining vestiges of democracy in Jammu and Kashmir. A smooth transition from autonomy to complete integration was ensured by trampling the civil rights of its 14 million people under the sheer weight of military jackboots.

Even the pretense of democracy was discarded in doing this, making the residents of Jammu and Kashmir feel emasculated, humiliated and disenfranchised.

History of political, constitutional frauds

Political and constitutional frauds on Kashmir have been part of the last seven decades as Article 370 had been hollowed out and reduced, as infamously mentioned by former prime minister Gulzari Lal Nanda, to a “tunnel in the wall”, mostly through presidential orders and often papered with consent of the state legislature. Perhaps, the only similarity with the present case is the gross constitutional abuse in 1986 when the presidential order extended to Jammu and Kashmir Article 249 of the Constitution in order to empower the Parliament to legislate on the strength of a Rajya Sabha resolution and the concurrence was given by Centre’s own appointee, the then Governor Jagmohan.

Despite this similarity in the way concurrence was sought, August 5, 2019 presidential order was distinct as it signalled the absolute demolition of the edifice on which the compact between India and Kashmir was founded.

The constitutional change also sets a dangerous precedent for India’s federalism and its asymmetric federalism model, in which Jammu and Kashmir occupied the centre-space. Federalism has been part of the basic structure of India’s Constitution, as also upheld by the Supreme Court. Article 370 was an essential facet of India’s federalism because it governed the relationship of the Union with Jammu and Kashmir.

The August 2019 changes prompted A C Michael, Former Member of Delhi Minorities Commission to remark, “Through same act, Delhi’s statehood could be withdrawn by putting who is who of India residing in Delhi under house arrest. Same act, can be used to bifurcate states under the government of other political parties. A very dangerous precedence set by the present government for future governments. This is an emergency of another kind.”

The anxieties of the Centre repeating the J&K experiment elsewhere are deeper in several other states with certain special provisions. Article 35A closely resembles Article 371 of India’s Constitution that offers similar safeguards to the people of the north-eastern states with respect to government jobs, ownership and transfer of land and its resources. Under Article 371A, central laws do not automatically apply to the state unless approved by its legislature. The state enjoys full autonomy with respect to customary practices and laws with respect to land ownership and its resources. Similarly, in Manipur (Article 371C) and Arunachal Pradesh (Article 371H), the local laws safeguard the land and customary rights of tribals. With respect to Sikkim (Article 371F), even the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction has been restricted on issues of treaties. Ownership of property is also reserved in Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and parts of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, among other states. Maharashtra and Gujarat also enjoy a special status under Article 371. Under this provision, the President may provide for special responsibilities to the governors of the two states for establishing separate boards for Vidarbha and Marathwada (in Maharashtra), and Saurashtra and Kutch (in Gujarat), and equitable distribution of funds to these areas.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta aptly summed up the stealthy measures as a new form of repression “reminiscent of the Reichstag or Chinese constitutional ideology that sees federalism as an obstacle to a strong state and homogenous culture” and expressed concerns about India’s asymmetric federalism arrangements outside of Kashmir. He wrote that if such precedents of unilaterally declaring states to be Union Territory were to be applied elsewhere, we will simply become “a union of Union Territories that happen to be a state at the discretion of the Centre.”

“For the people of Jammu and Kashmir, what was lost was not just the special status of J&K with its emotive appeal but also the privileges and protections it gave to the residents of J&K.”

What changed for J&K

Several petitions challenging the J&K Reorganisation, including the de-operationalisation of Article 370, were filed in the apex court within weeks of the action. In July 2023, the Supreme Court began hearings on a daily basis and reserved the judgement. While that is expected to be delivered on December 11, 2023, the government has used J&K Reservation Act as basis for introducing sweeping legal and political changes in Jammu and Kashmir with far-reaching consequences. Many central laws have been extended to J&K and erstwhile state’s own laws have been repealed.

In a late-night move on March 31, 2020, one week after the Covid-19 nation-wide lockdown was announced, the Indian federal government announced the gazette notification altering over 100 J&K laws and totally repealing about 30 through a simple order called the J&K Reorganisation (Adaptation of State Laws) Order, 2020. More laws have been adapted, scrapped and altered ever since in the most arbitrary manner. The word ‘permanent residents’ was purged in the several clauses of various laws. More significantly, the Civil Services Recruitment Act was amended by replacing ‘permanent resident’ with ‘Domicile’, opening jobs in government services to Indian citizens outside the erstwhile state. Automatically, the clauses in all the acts of the J&K constitution, particularly with respect to jobs and land ownership, which required proof of being permanent resident – possession of a PRC – were rendered meaningless. In October 2020, the government repealed or altered 26 land laws with far reaching consequences for J&K’s population. Several other laws have been introduced since and fresh amendments were recently introduced or passed in the parliament.

For the people of Jammu and Kashmir, what was lost was not just the special status of J&K with its emotive appeal but also the privileges and protections it gave to the residents of J&K.

[i] A.G. Noorani, ‘The Kashmir dispute – 1947 to 2012’ – Volume II; Tullika books; 2013

[ii] Rakesh Ankit, The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India; Indian Economic & Social history Review; Aug 3, 2016

[iii] Stephen P. Cohen, Shooting for a Century: The India-Pakistan Conundrum; Brookings Institute, 2013

[iv]Article 370: A Short History of Kashmir’s Accession to India, August 6, 2019, EPW (https://www.epw.in/engage/article/article-370-short-history-kashmirs-accession-india)

[v] Constituent Assembly Debates, 17 October 1949 (Noorani: Kashmir Dispute 1947-2012: Volume 2)

[vi] In an interview with Krishan Dev Sethi, one of the members of the Jammu and Kashmir constituent assembly, who was also witness to the debates on Article 306A that later came to be known as Article 370.

[vii] Noorani, Kashmir dispute

Courtesy: Kashmir Times