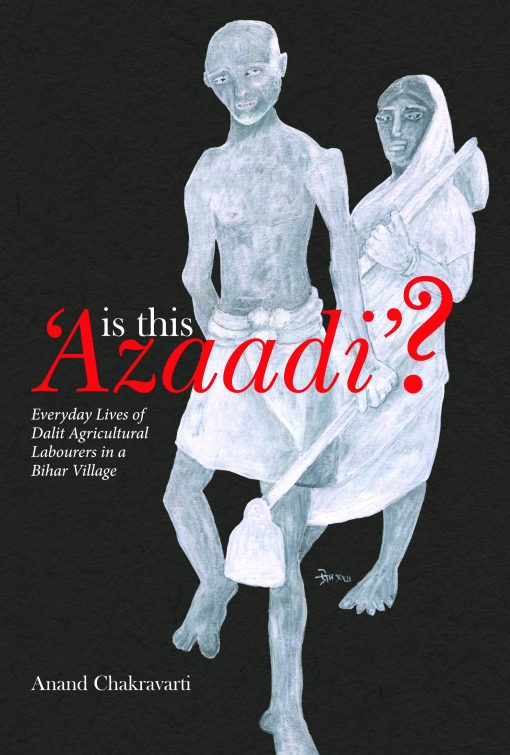

Dalit agricultural labourers’ struggle for food

Image Courtesy: Tulika Books

…the underclass in Muktidih is hopelessly on the margins of survival because of its limited access to the necessities of life, including food, clothing and shelter. One of my informants, …, insightfully stated that even insects were more capable of coping with their needs than were members of his class. This is a corollary of a situation where the terms and conditions of the employment of landless labourers (whose only resource is their labour power) are determined by their employers (who control the means of production). Labourers are therefore constrained to work for low wages (as shown in the preceding chapter), rendering them incapable of accessing essential needs in full measure.

Food

… Beyond rice (bhat), which is the staple food for rich and poor alike in this area, even the poorest labourer imagined that a complete diet would also include dal, tarkari, dudh, dahi (lentils, vegetables, milk and curd). Ironically, as one labourer remarked, ‘Only jamidars [landowners] can access lentils and vegetables on a regular basis. Even if they cannot produce sufficient quantities for their daily requirements, they can purchase what they need.’

[…]

Around mid-day, as I talked to Jeevan, then a leading member of the community, he drew my attention to a girl of about 10 standing close by. She was eating a dry roti, flavouring each morsel with some salt that she carried in the palm of her left hand. He spoke resentfully of the contrast between the diet of ‘our children’ (Bhuiya children) and the children of babu sahib (the Rajput landholders of Babugram). The latter, he implied, would never have to assuage their hunger in such a spartan manner. The sight of the girl somehow making do with a roti and salt made me conscious of the poor state of nourishment among the underclass in general. As meals are consumed privately, I only once got the opportunity to witness a meal while it was being eaten… . However, many labourers spoke pathetically about their food, which conformed broadly to what I witnessed.

[…]

The exclusion of lentils from Dashrath’s meals was by no means unique among the underclass. His statement that he could not afford dal, except occasionally, applied to all Paswan and Bhuiya labourers, who procured the item only once in ten or fifteen days. As described below, the regular inclusion of dal in the meals occurred when heet-natey (relatives) visited a household, and when there was a chance of earning a small quantity after the rabi harvest. Otherwise, on most days, as one Bhuiya man said, madh flavoured with salt and red chillies substituted for dal in all households.

Rice normally constituted the core component of a meal, both in the morning or at mid-day and in the evening. However, for a brief period after the rabi harvest (perhaps a month or two), wheat formed the base for the evening meal. While there was no apparent reluctance among Paswan households to eating wheat for one meal, I was explicitly told that Bhuiyas did so only out of compulsion. Thus, a Bhuiya labourer expressed his liking for rice by asserting that his community excelled all the others in its capacity to consume this cereal: ‘We are Bhuiyas; no other community can consume more rice than us!’

The nature of a labourer’s employment determined the principal source of the rice consumed by his family. For a halwaha, an unfree farm servant, and his family, the source of much of the rice consumed was the entitlement to paddy on the piece of land allotted to him by his employer, as well as the paddy earned for every nineteen days of work. In addition, a halwaha and the working members of his family earned paddy during the harvesting season. The main source of the rice consumed in the household of a casual labourer was from the wages in kind earned by him and the working members of his family for harvesting paddy in the kharif season. A small amount of rice could also be bought through the cash component of the daily wages earned for various agricultural operations.

… large amounts of foodgrain were used to redeem debts incurred during the preceding season, including those for tiding over food deficits. Therefore a deficit in one season generated a deficit in the following season too, because a sizeable quantity of the grain produced or earned during the latter was used for redeeming debts from an earlier time. …

Bhola Bhuiya, a halwaha, was among the few persons who gladly answered all my questions. At that time his household included his wife, a married teenaged daughter who had not yet moved to her affinal home, and a 10-year-old son. On the day I spoke to him (12 October 2001), the previous evening’s meal had comprised roti with a mixture of salt and crushed red chillies. Bhola specifically mentioned that neither he nor the members of his family had had enough to eat. He had eaten three rotis, but had wanted one more to feel satiated. Some time before I met him, the family had eaten the morning meal comprising madh-bhat and a stew made from saag (a cheap leafy vegetable), which sold for Rs 2 a kg. The evening meal was likely to conform to the same pattern as the meal the previous evening, and therefore the family would not have enough to feel satiated.

The principal reason for the deficiencies in the food consumed by Bhola’s family, in terms of both quantity and quality, was the fact that the basic items (rice and wheat) had been taken on loan, and caution had to be exercised to ensure that they lasted as long as possible. … His household had been in a state of deficit much before September, and he could only hope that there would be enough foodgrain for consumption after the forthcoming Aghani harvest. …the amount of foodgrain borrowed was indeed staggering, including 3 maunds and 25 seers of rice and 2¾ maunds of wheat. The huge deficit in Bhola’s stock of foodgrain was mainly attributable to the marriage of his teenage daughter in May that year, which demanded a series of customary feasts for the members of his tola.

[…]

The visits of relatives, an inevitable part of family life in general, had a major impact on the household budgets of the underclass. Indeed, the principal reason for the premature depletion of Jeetu Paswan’s stock of rice in April 2001… was the visit in March–April of a group of affinal relatives who stayed for a fortnight. …They had come to propitiate a deity in the neighbouring village of Babugram. The deity was said to possess miraculous powers to cure people suffering from serious diseases and to ensure that they maintained good health. Jeetu or his wife accompanied the group daily to propitiate the deity. The former bore the expenses on prasad (offering of food to a deity) as well as snacks for his sister-in-law’s children, all of which required him to have enough cash. He said that he spent liberally, as the visits to the deity cost him Rs 1800. Apart from this, dal was included in the meals frequently during the visit of his relatives. He claimed that he could afford the expenditure because he had supplemented his earnings as an agricultural labourer by working in the brick kiln in the neighbourhood of Muktidih.

[…]

As the rabi harvest was in progress at the time of speaking to Hiteshwar in April 2001, I wondered whether the wages in kind earned by him would be of any significance for redeeming his debt. He replied in the negative, because whatever he and his son earned as wages would constitute the base for the evening meal in his household for about a month.

… I spoke to Subhash Bhuiya (50), a casual labourer, in October 2001… . His household included his wife and an adult son (about 20). They had been unemployed since the completion of paddy transplanting operations, and had been surviving since mid-September mainly on borrowed rice and money borrowed to purchase rice. Subhash’s meal comprised just madh-bhat flavoured with salt. He stated that this was most likely to be the only meal his family would eat on that day because of acute financial constraints. Some days earlier, he had borrowed Rs 50 with great difficulty and procured 4 kg of rice. By undereating, or by missing a meal, he hoped that the rice would last his family for four days. He also mentioned that when the quantity of rice fell short of the requirements of a household in his tola, the practice was to double the quantity of water normally used for cooking it, thus increasing the volume of madh-bhat to provide servings to all its members.

It is beyond doubt that the problem of accessing food punctuated the everyday lives of labourers in the local agrarian economy.

This is an extract from the third chapter ‘Surviving at the Margins: The Struggle for Basic Necessities’ of “Is This Azaadi? Everyday Lives of Dalit Agricultural Labourers in a Bihar Village,” published by Tulika Books in 2018. Republished here with permission from the publisher.

First Published in Indian Cultural Forum