The 1990s were the beginning of collapse of a construct, the Indian republic, a secular state, a collapse moreover that took place in full public view. It can be safely said that the collapse continues and it is uncertain yet, the form in which a firm reconstruction, if at all, will or can take place. Bearing witness then, is a powerful and instinctive quality of that rare species, the scribes and editors who believe that with real truth-telling the unveiling of the processes behind catastrophic events is key.

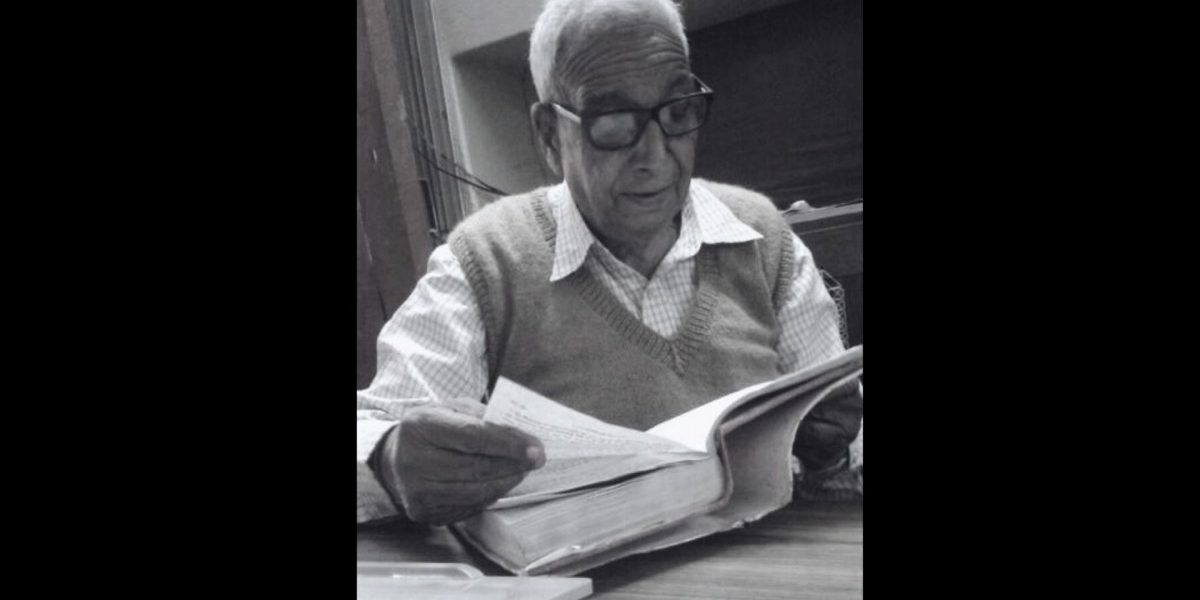

Sheetla Singh, the indomitable editor of Jan Morcha, was there and did that, several times over. Not as an individual player but as the Lighthouse Keeper or Light Keeper of a Lighthouse of the 65-year-old newspaper, published from the historic site of Faizabad, around which was centred a bitter man-driven conflict for decades. The Lighthouse Keeper, as a priceless and well documented analogy goes, is a beckoning light, guiding ships safely into the harbour. The lighthouse cannot uproot itself, wade out into the water, grab the ship etc. No. The ship has some responsibility for its own destiny, but it can choose to be guided by the light in the lighthouse. Or it can go its own way, even hit the rocky bottom and sink.

The fact that Jan Morcha survives still in this age of cynical commercialism, the fact that it is a newspaper one can feel and touch every morning in a fine, readable Hindi, never mind if its pages have been reduced to eight from 12, is part of this amazing resilience. That you needed a Sheetla Singh in the driving seat with a band of committed scribes (and how can we not mention Suman, a close aide and colleague?) is another part of the whole. Sheetla Singh was a trained and committed communist and leftist-socialist, yet journalist par excellence who debated long hours with friend and fellow guide, Justice P.B. Sawant, the structural and ethical issues facing media (Jan Morcha is a unique experiment in cooperative ownership; Jan Morch’s editor never failed to point out how the first press commission, which was formed under the chairmanship of Justice J.S. Rajadhyakhsa on September 23, 1953 by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, believed that the freedom of expression of newspapers was under threat because proprietary interests influenced editorial content and therefore cooperative ownership by journalists was the answer).

Sheetla Singh bore witness to the build-up of the blood and gore that drenched Faizabad-Ayodhya in the early 1990s. Much has been written already about how on October 30 and November 2, 1990 instead of sensational headlines titillating readership with the violence (in the rest of the competitive Hindi media at the time, Ayodhya Bathed in Blood and Blood Flows in the Sarayu), it was Jan Morcha under the editorship of Singh that carried the report about 16 people having died in police firing. Facts not ideology was Sheetla Singh’s guiding principle though he was quick to see, and feel, how the previously shrill support of large sections of Hindus for the shrill and violent politics of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad was diminishing, even in the ‘temple town’ of Faizabad-Ayodhya.

Memory has relegated both Sheetla Singh and the Jan Morcha’s role in collaborating on the Citizens Tribunal in Ayodhya-An Inquiry Commission consisting of Justices O. Chinnappa Reddy, D.A. Desai and D.S. Tewatia. Given the lapses in journalistic and public memory, the failure of publications and scribes to recount and recall the historiography of communal violence, this Report of the Citizens Tribunal on Ayodhya is a precious and sombre resource. Sitting in the conflict ridden township that has been the site of this violence, witness testimonies and government records fed into the powerful findings that pointed to not just the failure of intelligence and law enforcement to prevent the actual demolition of the 450-year-old Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, but the processes behind deep Central government and state government complicity in allowing the demolition to take place.

Recording with gratitude the space and facilities offered by Jan Morcha, the report documents how the Faizabad-Ayodhya Muslim community bore the mental and physical brunt of the destruction around and with the fall of the iconic Masjid. “The damage to property was extensive. According to the Muslim relief organisations, 267 houses, 23 mosques and 19 mazaars were destroyed or damaged. Government estimates are substantially lower. According to official figures only one mosque and two graves were substantially destroyed, and 542 Muslim residences were destroyed and looted, with losses estimated to be Rs. 1,91,39,400.” [A simple arithmetical exercise puts the physical losses, at a staggering Rs 14 crore. This figure is one more testimony to repeat losses suffered by the Muslim community year on year, each time a targeted bout of violence spills on the streets. This tribunal report on Ayodhya is matched in historiographical value with the Justice B.N. Srikrishna Report into the Bombay 1992-1993 post Babri demolition violence and the Concerned Citizens Tribunal – Crimes Against Humanity (CCT, Gujarat), 2002.

There are 365 days in a year and for 65 years, Jan Morcha reported facts and perspective, becoming an invaluable source of independent journalism – albeit in a non-digital form – for six and a half decades. Through this the newspaper’s lead voice, Sheetla Singh who passed away after a brief illness on May 16, 2023, was an old-world senior journalist and visionary activist who connected with all and each of us in so many ways. If I have picked on 1990 and 1992 as a means to understand the special role that journalism like that manifest in Jan Morcha plays, it is for a reason. Bearing witness has unique evidentiary capacity and the Jan Morcha report, dated February 25, 2002, available as Annexure 7 to the Citizens Tribunal—Crimes Against Humanity, Gujarat 2002, Volume I, reminds us the process behind the violence that erupted first in Godhra on February 27, 2002 and then engulfed 19 districts of the state, had a causality and process behind it.

Instead of paraphrasing this small news report, importance lies in its reproduction:

“Annexure 7

Janmorcha Report

(Jan Morcha, edited by Sheetla Prasad, is a Hindi daily published from Ayodhya. The paper carried the following story on 25 Feb. 2002).

Bhelsar (Faizabad), 24 February: Trishuldhari Bajrang Dal workers, travelling to Ayodhya on board the Sabarmati Express this morning, let loose a reign of terror upon dozens of helpless Muslim passengers, burqa clad women and innocent children. They also targeted the people waiting at the platform, forcing them to shout the slogan, ‘Jai Shree Ram!’ A few even declared themselves to be Hindus in order to escape their wrath.

According to eyewitnesses, close to 2,000 trishul carrying Bajrang Dal workers on board the Sabarmati Express coming from the direction of Lucknow began indulging in these activities from the Daryabad Station. Anyone identified as a Muslim on the train was mercilessly attacked with trishuls and beaten with iron rods. Even women and innocent children were not spared. Burqas were pulled off, women were beaten with iron rods and dragged, people waiting at the platform were also similarly targeted.

This continued between the Daryabad and Rudauli stations. According to an eyewitness, a youth who protested against this barbarism was thrown off the train between the Patranga and Rojagaon stations. Several women, badly wounded and covered in blood, jumped off the train as it pulled into Rudauli around 8 a.m. The Bajrang Dal activists also got off the train and started attacking those whom they identified as Muslims from among those present on the platform.

Ata Mohammad, from Takia Khairanpur, waiting to catch a train to Allahabad, was badly beaten; some others were forced to shout, ‘Jai Shree Ram!’ Some escaped by declaring that they were Hindus. 50-year-old Mohd. Absar who lives near the station was grabbed as he stepped out of his house. His long beard was rudely pulled before he was repeatedly stabbed with trishuls. Another man from the Rudauli police station area who happened to be at the station was badly beaten with iron rods. Local residents rang up the police.

By the time the police chowki-in-charge, Bhelsar, arrived at the station, the train had left and the injured were being rushed to the hospital. No report was registered at the police station since the officer-in-charge was unavailable. The injured have no idea why they were attacked. Rumours are rife. The people are petrified; respected Hindus and Muslims of the area have condemned the shameful attack, Muslim religious leaders have appealed for peace and requested that there be no retaliation.”

The rest, as is commonly said, is history. With every effort made by a rapacious state to erase from public and judicial memory records of this cynical collapse of constitutional protection, Sheetla Singh and his Jan Morcha that provided key and irrefutable evidence from the ground, will have the last laugh.

I have always been intrigued by his rather special name, Sheetla. A term, Sheetala that means ‘coolness’ or ‘cool’ in Sanskrit, the name evokes a rather special deity to whom devotees offer worship and prayers to remain safe and protected from diseases on an auspicious day. Sheetla Singh and Jan Morcha have, in so many ways, protected us from the all-pervasive scourge of revisionist and targeted hate.

Teesta Setalvad is secretary of Citizens for Justice and Peace, which advocates for human rights for marginalised sections, a journalist and co-editor of Sabrangindia. She is the author of Foot Soldier of the Constitution: A Memoir.

This article was first published on The Wire