Bengaluru (Karnataka) & Mousuni (West Bengal): Two years back when theatre director Nimi Ravindran, 43, got a grant to teach theatre to students at a public school, she was confident her fluency in the local language, Kannada, would be enough to communicate with the students. Instead she found that all but one of 20 fifth graders at a Kannada-medium public school in Bengaluru’s Marathahalli area spoke Bengali.

Bengali-speaking children, like those in the bridge school centre in Bengaluru, above, have travelled more than 2,000 km from districts bordering Bangladesh. Some of these children are climate change refugees from Sundarban. As many as 40% of students in some Kannada-medium government schools in Bengaluru speak Bengali, according to the Samridhdhi Trust that runs bridge schools to help these children cope.

“Most of them said they were from West Bengal. I wondered what these children were doing so far from home,” Ravindran said. As she started conducting workshops in Hindi, that the children were somewhat familiar with, their stories started flowing.

“They spoke about the trees near their homes, the spirits that lived in them and the clean air. They missed their home,” Ravindran recalled.

The Sundarban delta–nearly one million hectare in area–is formed at the point where the rivers Ganga, Brahmaputra and Meghna merge into the Bay of Bengal. The delta is extremely fertile as the three rivers carry an estimated one billion tonnes of sediments.

Nearly 40% of Sundarban–the world’s largest mangrove forest, three times as large as Goa–is in India, the rest is in neighbouring Bangladesh.

Sundarban (literally ‘beautiful forest’) features in the list of UNESCO’s 209 natural heritage sites in the world for supporting “an exceptional level of biodiversity in its terrestrial, marine and aquatic habitats”.

Over the last 40 years, Sundarban has lost 220 sq km–nearly the size of Kolkata–to the sea, according to Sugata Hazra, director of the School of Oceanographic Studies at Jadavpur University.

As rising sea levels engulf entire islands, residents are migrating en masse, from the Bangladesh as well as the Indian side of Sundarban.

Not all are environmental migrants, but with no documentation of this kind of migration, the numbers are hard to estimate.

But ripples of this migration are being felt over 2,000 km to the southwest. As many as 40% of students in some Kannada-medium government schools in Bengaluru speak Bengali, according to the Samridhdhi Trust that runs bridge schools to help these children cope.

IndiaSpend tracked some of these migrants from Sundarbans to the Kalihata slum in east Bengaluru’s Marathahalli area. Studies show that several districts of West Bengal, not just in Sundarban but across the state, are extremely vulnerable to the impact of climate change.

By 2060, nearly 1.4 billion people across the world will be at risk of becoming environmental migrants, some internal and others flocking across borders. The annual rate of sea level rise is expected to triple by the year 2100, making agriculture as well as everyday life in low-lying places, like Sundarban, unsustainable.

This is the third story in our series on how climate change is disrupting people’s lives (you can read the first story here and the second here). The series combines ground reporting from India’s climate change hotspots with the latest scientific research, and highlights how people are adapting to the changing climate.

The Sundarban delta, home to the world’s largest mangrove forest, is at risk from rising sea levels because of global warming.

One in 10 individuals living in a low-lying coastal area on this planet is in India. Along with China, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam, India has the highest population that will be exposed to the impact of flooding and extreme weather events that the rising sea will bring, according to a 2015 study.

Human activities have already caused global warming by 1 degree Celsius, according to the September 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world body for assessing science related to climate change. Governments of 195 countries are on this panel.

“Over 90% of the heat trapped in the climate system is actually in the oceans. As the oceans warm, just like liquid in a thermometer, it expands and (the) sea level rises,” said John Church, research scientist and one of the lead authors for the chapter on sea level rise in the IPCC’s fifth assessment report.

Melting of non-polar ice, like that in the Himalayas, the thermal expansion of oceans as they warm, and the melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are pushing up global sea levels.

“With unmitigated emissions the sea level rise could be as much as one metre by 2100,” Church said. If the entire ice sheet over Greenland were to melt, that alone would cause global sea levels to rise by seven metres. If all the ice sheets in Antarctica melt, it could push the levels up by another 55 m.

A video by the European Space Agency (ESA) explaining what contributes to sea-level rise.

Sea levels will continue to rise not just through the century but well past 2100. For people living on small islands, low-lying coastal areas and deltas, this means, at best, that more salt water from the sea will enter their fields making the soil unsuitable for agriculture, there will be increased flooding, frequent cyclones and infrastructure damage. At worst, it means the piece of land they call home would be under water.

Scanty research on the India side of Sundarban

The changing climate in the Bangladesh side of Sundarban is well documented but not much is known about the Indian side, according to Selvin Pitchaikani, an oceanographer at the Institute of Environmental Studies and Wetland Management (IESWM) in Kolkata.

Pitchaikani, who published his data on the changing weather patterns in Sundarban in 2017, found that the land is increasingly growing saline and that cyclonic storms have become frequent. Rainfall patterns have already changed, making conventional cultivation difficult for farmers, his research found.

But “to come to any conclusion, we need data for a minimum of 20-25 years. We need more weather stations in the region as well as funding”, he said emphasising the need for more research.

With migration, children grow up without a parent, fewer people to care for the elderly

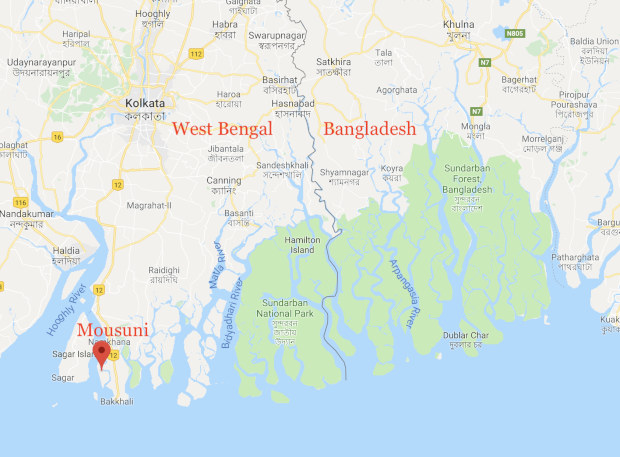

It’s a four-hour car ride from Kolkata to the Sundarban delta region. Once here, a car becomes useless. To reach the island of Mousuni, it’s another hour-long journey of switching between electricity-powered rickshaws while on small stretches of land, and small boats to cross the streams.

Electricity reached Mousuni–one of the larger islands in the delta with a population of over 25,000–a year ago, trailing climate change by decades.

Mousuni is an island in the Sundarban delta with a population of over 25,000 residents. Frequent floods and the rising sea level have forced many to migrate from Mousuni.

Sheikh Sufi, 27, grew up in Mousuni. His home is on the coast overlooking the Bay of Bengal. “We used to grow rice and chillies but a decade back there was severe flooding. After that the crops haven’t grown,” Sufi said, holding his three-year-old son Abdul Rehman over his shoulder. Once their land became infertile due to salt water, they learnt to fish. Now, six months a year, Sufi travels over 2,000 km to Kerala to work as a construction worker earning about Rs 300 a day.

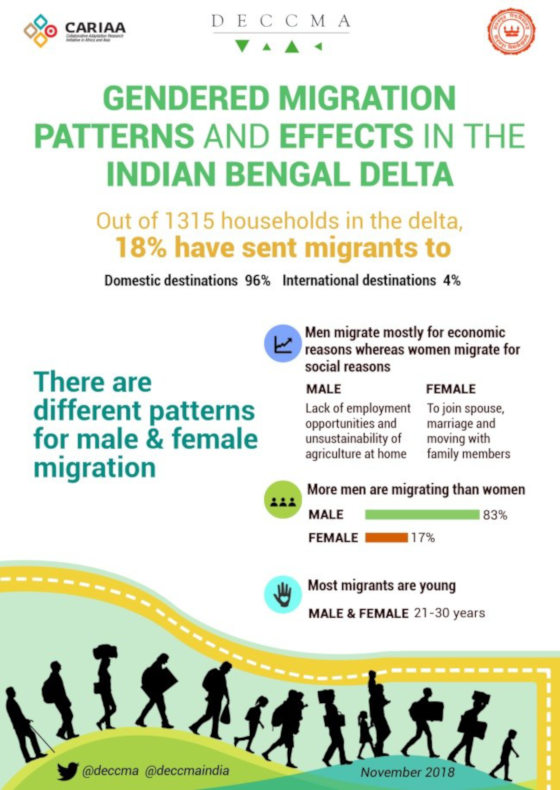

Like Sufi, nearly 96% of these environmental migrants are headed to other areas within India, according to a study of 1,315 households in the region. The study was conducted by Deltas, Vulnerability & Climate Change: Migration and Adaptation (DECCMA), a consortium of researchers from universities in UK, Ghana, Bangladesh and India.

Of these migrants, 83% are men and 17% women. Most are young; between the ages 21 and 30. The men interviewed for the study said they were moving for employment opportunities as agriculture was unsustainable. The women were moving to either join their husbands post marriage or to live with other family members.

Left behind are the elderly, children and most women.

“There are two types of migrations–proactive, who plan their retreat from the coast in advance and reactive, who move only when there is no other alternative left. In Sundarban we are still witnessing reactive migration,” said Indrila Guha, principal at Basanti Devi College, Kolkata and a researcher in environmental economics.

Children growing up without a parent, fewer people to care for the elderly, and poor women who could become easy targets for traffickers, are some of the potential fallouts of this situation, according to Guha.

For the ones who move with their families in tow, life continues to remain tough. The children in Bengaluru’s bridge schools struggle to adjust to life in the city, the language barrier making it even more challenging for them to adjust. Parents frequently move in search of jobs and education is one of the first casualties.

Deltas, Vulnerability & Climate Change: Migration and Adaptation (DECCMA), a consortium of researchers from Universities in UK, Ghana, Bangladesh and India is studying the impact of climate change in river deltas.

Source: http://generic.wordpress.soton.ac.uk/deccma/

Residents adapt to rising seas

As the onslaught of the sea continued, Sufi’s home was reduced to rubble. During high tide, the sea waves wash away chunks of his house. On a low tide day, like the one when IndiaSpend visited, his home provides a view of the sea that tourists scout the globe for.

Sufi, his wife and young son live with a neighbour. “We have no money to build another home. Where can we go?” he said, with eyes downcast.

Sheikh Sufi, 27, outside his destroyed home in Mousuni. Sufi works as a construction worker over 2,000 km away in Kerala for six months in a year.

“We have no policies directed at rehabilitation and resettlement of people who have lost their land due to sea level rise and coastal erosion,” said Hazra, of Jadavpur University.

Rainfall is usually heavy, and severe cyclonic storms frequent. This area receives 1,501-2,500 mm of rainfall, compared to the Indian average of 801-1,500 mm.

Those who haven’t migrated try to adapt. Shabir Sheikh, 27 and Khushbanoo Bibi, 25, married for 12 years, are constructing a new home for themselves and their three children, on higher ground.

“During floods, the stove gets wet and so we are making sure in the new home it will be higher so flood waters don’t reach it,” Khushbanoo said. Most women here cook in the open, on mud stoves and firewood, which makes it impossible to cook during the floods.

Shabir Sheikh and his wife Khushbanoo Bibi’s new home is being built at a higher level to keep flood waters at bay.

The government is helping by building embankments along the coast to stem the flood waters, and flood shelters to accommodate those affected by floods. There are no long-term policies to help relocate and rehabilitate residents.

Adapting To Changing Climate: The Sundarban Delta

Double burden of rehabilitation and poor health in Sundarban

Globally, of the regions in the low lying coastal areas at the risk of flooding, most are underdeveloped or developing.

Nearly a third of the children under the age of five in South-24 Parganas, the district where Mousuni is, are stunted–short for their age. Half of the households still lack modern sanitation facilities and as many six in every 10 women are anaemic. Yet, the district is now having to prioritise infrastructure to deal with climate change.

Depending on the material used to build the embankment, a one-km long section could cost as much as Rs 1 crore. As seas rise, locals plead for the government to build more walls even as they are aware that these are just short term measures against climate change.

Threat to biodiversity

More than 200 species of plants, 400 species of fishes and 300 species of birds, numerous phytoplankton, fungi, bacteria, zooplankton, reptiles, amphibians and more call Sundarban their home. Even within Sundarban, species differ depending on the salinity of the soil. Sundarban is also home to many threatened and endangered animals like the Royal Bengal tiger, estuarine crocodile and the Indian python.

The changing temperature of water and increased salinity and acidity in the soil has already impacted the region’s biodiversity, according to studies by the Marine Science Department of Calcutta University and the Department of Biological Science of the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Kolkata.

While the rising sea level impacts biodiversity, experts also blame human activity. “If, for instance, there were no obstructions on the major rivers and flows were not diverted, eroded material would have reached the delta,” said Anurag Danda, senior advisor for Climate Change Adaptation at the World Wildlife Fund.

“Between the Tehri dam (Uttarakhand) and Farraka barrage (Murshidabad, West Bengal), there are at least 1,000 interventions along the Ganges that either divert water or hold water resulting in much reduced sediment delivery,” he explained.

Problems for nature and man will continue to grow as sea levels continue to rise, scientists say. “The question would be not whether it would happen but how quickly it would happen,” Church, co-author of the latest IPCC report, said.

What is the way out for those living along the coastline? Planned retreat to safer places, aided by the government, is the main option, Hazra said. “It will be economically beneficial as a whole rather than keeping people there and rebuilding embankments.”

This is the third in a series on India’s climate change hotspots. You can read the first story here and the second here.

(Disha Shetty is a Columbia Journalism School-IndiaSpend reporting fellow covering climate change.)

Courtesy: India Spend