In June this year, about a hundred people from Nuagaon village near India’s east coast marched towards a wall that the Odisha government is building around a 1,700 hectare piece of land on the village’s periphery. The wall would mark the inclusion of the land–1,253 hectares of which is forest land and is under dispute–in the state government’s land bank, thereby restricting locals’ access to an area where they have traditionally harvested betel leaves, rice and fish.

The wall that the Odisha government is building around a 1,700 hectare piece of land on Nuagaon village’s periphery to mark the inclusion of the land in the state government’s land bank, thereby restricting locals’ access to an area where they have traditionally harvested betel leaves, rice and fish. In July 2017, villagers filed a petition against the wall’s construction; this picture was filed as part of the petition.

Faced with heavy police deployment, the villagers turned back to consider a change of strategy. In 2011, they had successfully fought off South Korean steel giant POSCO’s plan to set up a steel plant on the same piece of land. No sooner had POSCO announced in March 2017 that it would return the land to the state government than the government announced it would put the land into a land bank–not return it to the villagers.

When the government began to wall off the contested land in May 2017, the simmering discontent erupted.

The face-off in Nuagaon village finds echoes in land conflicts brewing across the country. State governments are rushing to build land banks, using both private and common lands, in an effort to attract investment in manufacturing and infrastructure. Up to 2.68 million hectares of land–an area larger than the state of Meghalaya–have been set aside in land banks in the eight states that declare these statistics, data from state government websites show.

These are: Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh.

In several cases, this has been done at the cost of people’s rights: Delhi-based data journalism initiative Land Conflict Watch has documented four recent cases including Nuagaon that together involve more than 3,550 hectares of land and affect 258,000 people–more than the population of Nagaland. These conflicts have arisen because state governments have banked land that was allotted for industrial and infrastructure projects that were shelved due to local opposition. Instead of resolving the conflict, the states just locked the land away.

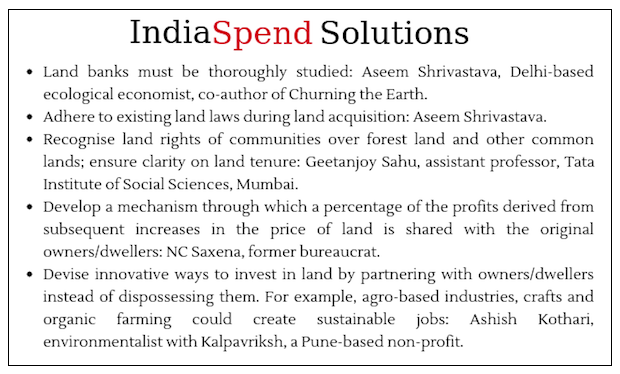

Land rights activists say the idea of land banks is problematic in itself. “They steal land from villages and reverse long-needed land reforms,” Aseem Shrivastava, a Delhi-based ecological economist who co-authored Churning The Earth: The Making Of Global India, told IndiaSpend. And recent conflicts show that state governments’ methods of creating land banks have been questionable.

Why land banks

State governments began to “bank” land in the 1990s, particularly in the post-liberalisation period, Michael Levien, professor of sociology at Johns Hopkins University in the US, and author of the forthcoming Dispossession After Development: Land Grabs in Neoliberal India, told IndiaSpend in an email.

“From the point of view of the government, building land banks allows them to offer land to private investors right away, rather than having to wait for the lengthy process of land acquisition each time an investor wants land,” he said. “Investors also like to know that the land is acquired and available, and that they won’t run into political problems down the road.”

Making land readily available for economic activities sounds like a rational move. Scratch the surface, however, and a different picture emerges–of conflict, and denial of people’s rights.

Source: State government websites

Note:NA= Not Available in Public Domain

Banking disputed land—the case of Nuagaon

When POSCO signed an agreement with the Odisha government to set up a steel plant in Nuagaon and nearby villages in 2005, the 700 families affected were not enthused.

Mostly Dalits or Santhal tribals, the villagers wanted to continue to earn their livelihood from the forest, and did not believe that jobs or other compensation promised to them would improve their lives. A decade-long resistance including legal challenges followed, at the end of which POSCO shelved the project in 2015.

In March this year, POSCO offered to return the land to the state government.

The villagers rejoiced, but were soon faced with another claimant–the state government, which quickly moved to add this land to a land bank it has been building since 2007. The Industrial Development Corporation of Odisha (IDCO) started to wall off the 1,700 hectares near Nuagaon in late May. The wall will eventually fence off the nearby Dhinkia and Gobindpur villages too.

Most of these families have farmed beetle leaves for generations, which they sell to earn a livelihood. They have no other employable skills.

Over generations, the locals have developed a deep bond with the land and the forest, beyond merely as a source of employment and their only possession, Prashant Paikray, an activist who worked closely with families here during their fight against POSCO, told IndiaSpend, adding that it is often this attachment that fuels their fierce resistance to industrial projects.

The encounter with the police made Nuagaon residents take legal recourse. In July 2017, they filed a petition with the Kolkata bench of the National Green Tribunal.

“Odisha government cannot put this forest land into the land bank,” their counsel Ritwick Dutta told IndiaSpend, explaining that according to the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, the government is required to get forest ‘clearance’ or approval from the central environment ministry to use forest land for a non-forest purpose. However, there is no provision to obtain forest clearance for a ‘land bank’ under the Act, Dutta said.

The petition adds that under the Forest Rights Act of 2006, the government cannot change the use of forest land without recognising the land and forest rights of people living or dependent on it since generations.

The residents of Nuagaon, Dhinkia and Gobindpur villages have submitted applications to the state government to claim their land and forest rights, but these have gone unaddressed since 2011. “The government is violating Forest Rights Act by preventing communities’ access to their forest,” Shankar Pani, an independent lawyer based in Odisha, told IndiaSpend.

The state government counters that the land had already been diverted for a non-forest purpose and was being held by the Industrial Development Corporation of India. “[T]here is no question of settling forest rights now,” Debi Prasad, the former industries minister with the Odisha government who put the disputed 1,253 hectares into the land bank, told IndiaSpend.

Dutta argues that the Odisha government never issued a final order diverting this forest land for non-forest purpose, as state governments are required to do after the central environment ministry issues a ‘clearance.’

Conflict everywhere

Odisha’s land bank now comprises about 40,000 hectares. Most Indian states either already have sizeable land banks or are in the process of creating them–largely for industrial or infrastructure development–although only eight make details publicly available (See table 1).

Conflict arises when industrial or infrastructure projects are proposed on land that communities inhabit, earn livelihood from, or have customary rights over. Over 200 million Indians depend on forestland for basic living needs, while 118.9 million Indians practise farming on 160 million hectares of land.

Land Conflict Watch has reported over 450 land conflicts so far, affecting more than 6 million people directly or indirectly. These include conflicts due to land acquisition by the state, violation of community rights over land, and opposition to industries such as mining and power generation and to infrastructure projects.

Often, communities do not want to part with their land, or their demands for compensation and rehabilitation are not adequately met. In some cases, the projects are shelved or cancelled and state governments take over the land.

“When [investment] proposals do not get fulfilled either due to lack of finance, on ground conflicts, regulatory failures or a combination of these, governments allocated the acquired land into land banks instead of repatriating it,” Kanchi Kohli, legal research director with the environment justice programme of Namati, a Washington DC-based global network of lawyers, told IndiaSpend.

Jharkhand’s clandestine move

Like Nuagaon in Odisha, a movement against land banks is building up in the Torpa block of Khunti district in Jharkhand. Members of gram sabhas (village councils) are holding meetings where they bring villagers’ land records to match with the land bank data available on the state revenue department’s website to check if the government has surreptitiously put any village common land into its land bank. Common lands are broadly understood as lands shared by all residents of a village and include grazing land, ponds and forests.

Their suspicion comes from the experience of Lohajimi, a village in Torpa, whose residents learnt in February this year that the state government had put about 60 hectares of their common land into its land bank. “The government didn’t even consult the gram sabha. This is a violation of PESA [Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas Act],” Rejan Gudia, a local activist from Lohajimi, told IndiaSpend.

PESA empowers village councils of scheduled areas–places primarily inhabited by tribespeople–to approve, reject or change the government programmes proposed in their regions. Khunti is a scheduled area.

So far, Jharkhand has banked about 40,468 hectares of land, 10% of which is in Khunti district’s Torpa block. Numerous calls and emails to Jharkhand government officials to ask under what provision Lohajimi’s land was put into a land bank went unanswered.

Lohajimi had previously been the epicentre of a three-decade movement that began in 1973 against the 700 megawatt Koel-Karo Dam proposed by the Bihar government (Jharkhand was then a part of Bihar). Lohajimi was one of the 132 villages that the dam would submerge.

Eight people died here in 2001 when police opened fire during a related protest. The government withdrew the project in 2003, and residents observe February 2 as Martyrdom Day every year. “The 60 hectares of land from Lohajimi that the government has banked was the part of the land where the dam was proposed,” Gudia said.

“Now the government is using land banks as another tool to acquire the same land,” another activist who did not want to be named told IndiaSpend.

Old v. new law in Chhattisgarh

In addition to common lands, land banks have violated laws protecting private land too, particularly in cases where land from cancelled projects has been diverted into land banks.

One such example is from Lohandiguda region in Chhattisgarh’s Bastar district. In 2007, the Chhattisgarh government acquired 1,765 hectares of land from some 2,000 families, mostly farmers, living in 10 villages in Lohandiguda. The land was acquired for Tata Steel to set up a steel plant.

Villagers alleged some of this land was acquired forcefully, and continuing opposition forced Tata Steel to withdraw in August 2016, blaming a breakdown of law and order in the region.

A few days later, the Chhattisgarh State Industrial Development Corporation (CSIDC) added this land to its land bank, swelling the reserve to 5,665 hectares. “The land is with the corporation. Papers are being prepared [to bank the land],” confirmed Alok Trivedi, General Manager of the Land Allotment and Land Bank Division in CSIDC.

Sudiep Srivastava, an activist-lawyer who splits his time between Chhattisgarh and Delhi, told IndiaSpend that legally, the Chhattisgarh government cannot include the land acquired for Tata Steel in its land bank until the government has re-acquired it from the people. Srivastava has filed a petition in the Chhattisgarh High Court demanding that land acquisition be quashed and the land returned to the people.

Srivastava explained that according to the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act (LARRA) of 2013, acquisition lapses if land was acquired under the older 1894 statute and the acquired land is unutilised for more than five years. The government can set up a new project on the same land but it must reacquire it from the people by following the provisions of the new land acquisition law. These provisions include conducting public hearings and obtaining affected persons’ consent.

For one decade, when it was unclear whether the Tata Steel project would go through, Lohandiguda farmers were in a limbo. None got the jobs they were promised; most were not rehabilitated; and although many families continued to live on the contested land, they could not sell their crops to cooperative societies or avail of farmer benefit programmes because the land was no longer in their name.

The situation got some political attention in August 2017 when Rahul Gandhi, vice-president of the Indian National Congress, during a tour of Bastar, accused the Chhattisgarh government of lying to the people.

New Indian law

The new land acquisition law gives land banks a freer hand. If land acquired under this law is unutilised for more than five years, the state government can put it in its land bank or give it back to the people it was acquired from.

The latter part has an interesting history. An analysis by Policy Research Studies, a research group for members of parliament, shows that the first draft of the LARRA Act prepared in 2011 had no option of returning unutilised land to the people, and allowed state governments to bank it instead.

That faced strident opposition from activist bodies including the National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM). “Our joint effort forced the government to add that the land could go back to people also,” Madhuresh Kumar, national convener of NAPM, told IndiaSpend, adding, “At least it provides legal backing to land losers who want to claim their unutilised land.”

Under the new law, if a state government acquires land for “public purpose”, which includes defence projects and housing for the poor, it does not need the consent of those who will lose their land. In contrast, the consent of 80% of the land owners affected is required for private projects and of 70% if the project is a public-private partnership.

The law does not prevent the government from acquiring land for a “public purpose” and later handing it over to a private player. “This would be a way to entirely circumvent the greater procedural requirements for private and public-private-partnership projects under LARRA,” Levien added.

Indeed, state governments are “breaking all kinds of laws” in order to acquire land to give it to industry or to put it in land banks, NC Saxena, a former bureaucrat who headed various committees on land rights, told IndiaSpend.

Saxena said keeping land fallow for long durations is a bad idea. “But land banks become a necessity because the current land laws are complex with lengthy land acquisition processes that the governments do not want to get stuck,” he said.

The new land acquisition law was supposed to resolve at least some of this complexity and shorten the procedures, but, as Saxena said, those goals have not been met and violations abound.

Shrivastava, the ecological economist, said each case of transfer into land banks should be investigated. “There is not even a single good study of this phenomenon by our social scientists,” he said, adding that investigation would undoubtedly unearth more scams.

Christopher Udry, a professor of economics at Yale University, says land banks should be created in such a way that they benefit landowners. Since 1981, he has studied rural economics and land rights in Ghana, a West African country the size of Uttar Pradesh, where 80% of the land is held by customary land owners, mainly families, clans and traditional authorities.

Udry proposes building land banks on the lines of traditional banks where people deposit their money–people could deposit their land and earn from it. “One can think of this as interest on the deposit,” Udry told IndiaSpend in an email. The managers of these land banks would let out the deposited land for commercial or development activities. “Payments could be structured in such a way that those willing to commit to longer terms receive higher payments,” Udry said, adding that the tenure of the deposit would be decided locally.

Experts would differ over whether this would work in India.

Meanwhile, the wall is fast approaching the Dhinkia and Gobindpur villages in Odisha, and communities are gearing up for a new battle.

(With inputs from Kanan Kapoor)

(Tripathi is an environment journalist with Land Conflict Watch, a Delhi-based data journalism initiative.)

Courtesy: India Spend