Representational Image

Over the decade to 2016, there has been a 20-percentage-point reduction in the number of girls married off before 18 years of age in India–from 47% in 2006 to 27% in 2016, as per Unicef. But this still leaves 1.5 million girls more vulnerable to domestic violence than those marrying later in life, concluded the study which was jointly conducted by the Indian Institute of Management, Indore and the Shiv Nadar University.

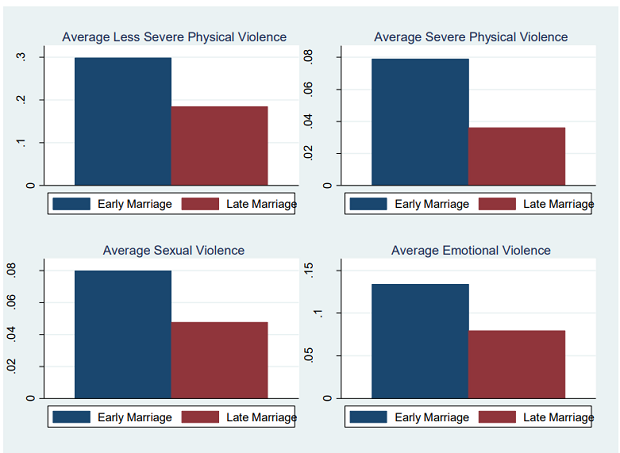

Incidents of “less severe physical violence”–such as pushing, arm twisting, hair pulling or slapping–could fall from being inflicted on 25% of all women to 18% with just a one-year delay in marriage. More severe forms of physical violence–such as kicking, beating, choking, burning, threatening or attacking with a weapon–could decrease from 6% prevalence to 2%, the 2018 study found.

If applied to the national female population (586 million as per the 2011 Census, 50% of whom are married), this means the number of women exposed to less severe violence could decrease by 20 million–from 73 million to 53 million, as per the study. Those exposed to severe physical violence is likely to fall from 18 million to 6 million.

Why are younger women more likely to face violence in a marriage? Women who marry early are more likely to have their studies interrupted, tend to be less assertive and less resistive to domestic violence, and hence, “safer to be victimized”, according to the study. Also, women who are forced to replace formal education with family responsibilities have fewer social and economic resources and reduced opportunities of empowerment within marriage available to them, the study added.

Violence against women is a significant global public health problem, with those exposed to physical or sexual abuse by partners 16% more likely to have a low-birthweight baby, more than twice as likely to have an abortion and almost twice as likely to experience depression. In India, 52% of women feel it is reasonable for husbands to beat their wives as a form of punishment, according to the National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-2016).

A causal link between early marriage and exposure to domestic violence underlines the importance of policies to tackle child marriage by incentivising families to continue girls’ education and delay their marriage. In India, both state (Kanyashree Prakalpa in West Bengal and Apni Beti Apni Dhan in Haryana, for example) and central (Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana) government schemes use economic, social and awareness-building methods to sensitise communities on the benefits of delayed marriage.

Parents, particularly in lower socio-economic and conservative groups, often begin thinking about a girl’s marriage prospects soon after she attains puberty. This anxiety is driven by various factors–the need to be freed of the responsibility and expense of caring for a child, a smaller dowry and the fear of an unwanted pregnancy.

“Puberty is associated with a child ‘becoming a woman’,” said Suparna Gupta, founder director, Aangan Trust, an NGO working to strengthen India’s child protection system. “Making sure a child is married off is (ironically) seen as a protective strategy, rather than a risk. There is a fear that adolescent girls are unsafe and will be targets of unwanted sexual advances and even attacks.”

To push an adolescent girl into marriage is much like pushing an adolescent boy into work and out of education–a coping strategy for poor families, Gupta added.

Gender inequality is seen as the primary cause of violence against women, driven by social norms and practices that attach less value to a women and normalise, excuse and tolerate domestic violence.

28% respondents experienced one or more forms of domestic violence

Using data from the National Family Health Survey 4 (2015-2016), researchers were able to establish the prevalence of different kinds of domestic violence among 9,343 survey respondents.

This is the first time a causal relationship has been established between age at marriage and exposure to domestic violence, which is categorised into four distinct types: Severe physical violence, less severe physical violence, sexual violence and emotional violence.

Of the survey respondents, 28% had experienced one or more forms of domestic violence mentioned above, said the study. This corresponds with World Health Organization figures, which say that globally one in three women have experienced partner violence.

A quarter of the new survey respondents had faced “less severe” physical violence (25%), 6% had faced “severe” physical violence, 6% sexual violence, and 11% emotional violence.

In every category of domestic violence, women married before they were 19 were found to experience higher levels of violence than those married later.

The largest difference between the age-groups were found amongst the “severe” and “less severe” categories of physical violence. Sexual and emotional violence was not found to have any statistically relevant correlation to the age of marriage.

Prevalence Of Domestic Violence By Age At Marriage

Source: The causal impact of women’s age at marriage on domestic violence in India, 2018

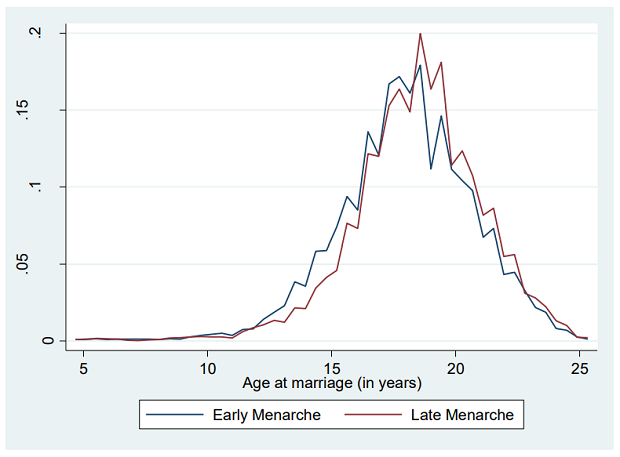

Earlier menstruation increases chances of early marriage

Girls who start to menstruate earlier–before 14 years of age–are also more likely (0.75%) to get married at 15 years of age than those who had a later menarche (0.49%), the study found.

Distribution of Women’s Age At Marriage By Age At Menarch

Source: The causal impact of women’s age at marriage on domestic violence in India

If social norms that support marriage at the onset of menstruation could be changed, more women could be protected from domestic violence, the results suggested.

“Things are changing though–other than social protection schemes, there is also political will. In Bihar, the chief minister has prioritised reduction in child marriage and declared this goal publicly in 2017. Police are engaged with the issue,” said Gupta.

Educated women too deal with domestic violence

The relationship between age and exposure to partner violence is not always negative, the study found.

Women who marry later may have more education, greater bargaining power within marriage and the ability to be more assertive but they might also face a “stronger backlash” from their partner, the study suggested.

“More education is undoubtedly good because it gives the women more opportunities, more resources, but at the same time, despite having these resources there are many other determinants that keep women in that (violent) relationship,” said Nayreen Daruwalla, director, programme on prevention of violence against women and children at SNEHA, a non-profit focussed on public health. “We have dealt with over 13,000 women in the last 18 years and we see even very educated women suffering severe forms of violence–unfortunately it [violence] is something which is very inbuilt in the family structure in India.”

The stigma attached to divorce or singlehood may further negate the empowering effects of increased education in the case of women, according to the study.

(Sanghera is a writer and researcher with IndiaSpend.)

Tish Sanghera – Tish spent three years as an advisor to corporates, NGOs and government bodies largely in the energy, tech and financial services sectors. A large part of her last role was writing thought leadership pieces and op-eds on behalf of clients for the European and US media. She is passionate about issues relating to climate, environment and urbanisation. Originally from the UK, she moved to Mumbai in 2017 and is a graduate of King’s College, London.

This article was first published on indiaspend.com