On March 22, K Mahesh, a district election officer of the East Delhi Parliamentary constituency served a show cause notice to the producers of the upcoming Modi biopic. Anand Pandey of Dainik Bhaskar and Sachin Chauhan of T-Series were given the show cause notice for allegedly violating the Election Commission’s Model Code of Conduct (MCC). The letter, as reported in Firstpost, stated that the film’s full-page ad published in the Hindi daily served as a “surrogate advertisement” of a PM candidate’s candidature. “Political overtures” of this nature, the letter stated, were violations of the Model Code of Conduct.

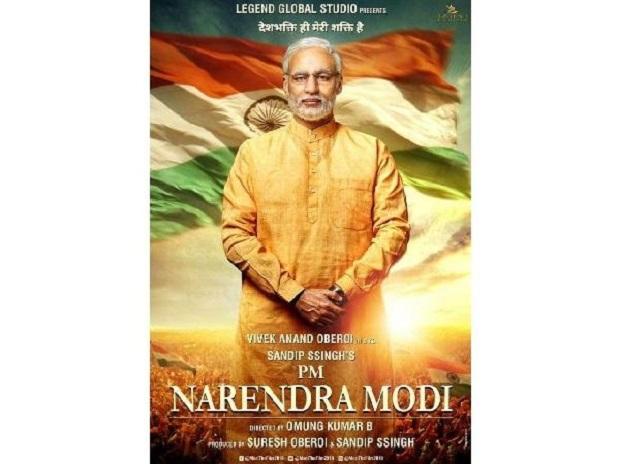

Image Courtesy: Business Standard

The biographical drama based on the life of BJP’s Prime Minister Candidate Narendra Modi has been in controversy ever since it was announced. Opposition leaders urged the poll body to intervene and delay the film’s release, which has been preponed to release in theatres on April 5, mere days before the first phase of polling.

What is the MCC?

The Election Commission of India’s Model Code of Conduct is a set of guidelines issued by the Election Commission of India for the conduct of political parties and candidates during elections mainly with respect to speeches, polling day, polling booths, portfolios, election manifestos, processions and general conduct. The Model Code of Conduct comes into force immediately after the announcement of the election schedule by the commission. For the 2019 Indian general election, the code came into force on 10 March 2019 and will remain so till the end of the electoral process. This is done to ensure that the ruling parties at the Centre and the State do not misuse their position of power to gain an unfair advantage.

What are the violations that the Modi biopic is accused of?

There are a number of violations that the Modi biopic film can be held for, the foremost being the silence period rule whereby no kind of canvassing is allowed between 48 hours of the election.

Speaking to the Indian Cultural Forum, lawyer Apar Gupta explains, “The most direct and evident harm is that a biopic on the prime ministerial candidate of the incumbent government has received indirect support in terms of a tacit approval sought by filmmakers amounting to a possible disguised attempt to canvass for votes. Hence, the candidate and political party will be circumventing all the prohibitions of the Model Code of Conduct and even the 48hour total silence zone. This may result in an unethical advantage towards them.”

Considering how the film has been accused of being an advertisement of the BJP’s PM candidate by the opposition, if the film, set to release on April 5, is likely to run in theatres till April 12 when the first phase of polling starts, it counts as a violation. In such a scenario then, do we factor in the probability that the proximity of a cinema hall and a polling booth, could be within 100 meters in some cases, which calls for another violation?

Model Code or “Moral” Code?

Since its establishment in 1968, the Model Code exists as a set of ethical guidelines bound by consensus amongst all political parties and candidates to ensure a level playing field. This means that it is not, however, legally binding. What are the implications/consequences for parties/candidates violating the codes?

Speaking to the Indian Cultural Forum, Former Civil Servant Kamal Jaswal said, “[While] the MCC does not by itself contain any penal provisions, if the violation is tantamount to a corrupt practice, then there are legal consequences.” Corrupt practices can be prosecuted under the representation of the People’s Act 1951. He also cited the example of Bal Thackeray’s disqualification. Thackeray’s speeches were found likely to incite communal hatred, which was held to be a corrupt practice and led to his disqualification.

By that logic, anyone who has seen the film’s trailer can testify to the film’s “appealing to caste/ communal feelings, criticising other political parties, aggravating tensions between communities – religious, linguistic etc.” Though Jaswal confessed that not having seen the film, he could not comment on the subliminal messages in the film with authority, he added that any move to incite violence was a criminal act, as per the law of the land. “Polls or not, such a behaviour was punishable under the representation of the Peoples Act (1951)”, he said.

Saffronisation of history

The trailer of Modi’s biopic has already glossed over the painful events of violence. Scenes where Modi is mourning over a burning Gujarat or even rescuing children during the 2002 massacres, is clearly inventive and adds to myth-making.

In his article for the Caravan journalist, Salil Tripathi argued that “the strategy to remake Modi begins with the claim that the Modi of 2014 is not the Modi of 2002; that he appears to have moderated his views”. Curiously, the biopic seems to be doing exactly that. Speaking to the Indian Cultural Forum, Tamil poet Salma said, “Usually these kinds of movies are made after the death of great leaders. But that is not so. This is purely for propaganda. People will understand this. Election commission should ban such kind of propaganda movies.”

But is it just the timing of the film that qualifies it as propaganda, or is there more to it?

Lawyer Apar Gupta affirmed that “the content, poster and timing, all external factors are to be judged if the determination is with respect to a plea that it is a proxy or an indirect attempt to canvass for a political party. There is a principle of law, what cannot be done directly, also cannot be done indirectly.”

Saffronisation of history aside, the key issue here is the timing of the film’s release. Release date only a few weeks ahead of the elections bears wide-ranging implications – to sway votes, promote Modi’s candidature and solidify a Hindu-nationalistic ideology.

It is understood that interventions in the media, no matter how late, have the power to influence election outcomes. But to what degree? In a tweet, writer Salil Tripathi said that banning the film would make a martyr out of it.

Speaking to the Indian Cultural Forum regarding his comment, Tripathi brought up a very crucial point about the extent to which such an opportunity can be exploited for political gains.

“If the courts or the CBFC were to delay the film’s release, in theory nothing prevents someone from streaming it from a server outside India, and make it accessible to viewers in India. And if that were to happen, people would see the film-makers as free speech martyrs, casting an unnecessary halo around the film.”

This is a crucial point when the policymakers of the EC framed their guidelines, they took into consideration the proliferation of texts, images, slogans, campaigns and posters, but propaganda through a full-length feature film was perhaps unanticipated.

Image Courtesy: Money Control

However, these provisions are applicable only if a link can be established between the ruling party and the film. So far the producers have denied any such link. They have clarified that the film is a private commercial enterprise. On inviting Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis and BJP president Amit Shah to promote the film, the producers said they invited them because Shah has a character based on him in the film and they wanted the film to be a “resounding commercial success”. But The Wire has reported of an (in)direct link between the BJP and the producers of the show.

Hitesh Jain, the lawyer for producers Anand K Pandit, Sandeep Singh, Manish Acharya and Suresh Oberoi, is a partner at Parinam Law Associates and a shareholder and director of BlueKraft Digital Foundation.

As per the report, BlueKraft has been closely working with BJP and its leaders for some time now. In 2017, it released the first book on “Mann ki Baat” at Rashtrapati Bhavan. In 2018, it partnered Modi as “technology and knowledge partner” for a book titled Exam Warriors, authored by Modi himself. This year on March 2, BlueKraft released the second book on Modi’s “Mann Ki Baat” titled A Social Revolution on Radio, 50 Episodes Special Edition.

What is art? What is propaganda?

“Art is based on truth. Propaganda through art is falsehood. We all know Modi’s hand in the Gujarat riots. And this movie says he is innocent. Do they think people will believe it? This is purely for propaganda.” Salma said.

The Indian Cultural Forum asked legal experts if there was a legal equivalent to the term “propaganda” without faltering into aesthetic judgments.

“Propaganda is a definition of social science which has broader girth and may not automatically denote a clear legal injury. This becomes important because while propaganda may usually have a negative connotation, it will have a high degree of subjectivity and hence fall foul of the constitutional tests which require specificity when a class of speech is restricted. For instance, defamation or hate speech,” explained lawyer Apar Gupta.

This also seems to be the vantage point the filmmakers are operating from. Speaking to IANS, producer Sandip Singh said “We are living in a democratic country where everybody has the freedom of speech. It’s very simple.”

How do we deal with this twisted nature of freedom of speech? Lawyer Gautam Bhatia told the Indian Cultural Forum that “there’s no legal distinction as such, and all forms of speech are protected under Article 19(1)(a); however, in one judgment called Motion Picture Association, the Supreme Court has hinted that pure propaganda might receive a lower level of constitutional protection (without defining it).”

Elaborating on the distinction further, Apar Gupta said, “there is speech and then there is media. While the paternal power of the State and legal regulation especially on cinema should be liberalised, it should not be allowed to become a vehicle for political propaganda. This, in fact, reinforces censorship. Such a situation is especially visible in Indian cinema where pre-certification is necessary through a board comprised entirely of political appointees. Hence, the entire process ensures that only the most flattering and uncritical portrayals of powerful persons, groups and institutions are permitted.”

But it seems that something has been missed here. Yesterday, the Bombay HC refused to interfere with Modi biopic release since the EC has already issued a notice to the director of the film.

Image Courtesy: Times of India

“This will come on the Internet. I don’t think that code of conduct is applied there”

As if the controversy over the biopic wasn’t enough, there is also a web series on Modi set to release soon.

Umesh Shukla, the director of Modi: Journey of a Common Man was quoted saying “This will come on the Internet. I don’t think that code of conduct is applied there”.

It makes one wonder if the fractions in the EC policies have enabled the getting away with a technicality in changing landscapes?

On March 17, Indian Express reported that the EC had called for a meeting with the India heads of social media platforms like Google, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, ShareChat and Tiktok on Tuesday, to discuss questions related to social media content during the Lok Sabha elections. This also included the pre-certification process for political advertisements, monitoring of content and the time limit for them to act on complaints.

The meeting came after the EC’s first takedown notice to Facebook regarding a Model Code of Conduct (MCC) violation on March 13. The EC issued a show cause notice to the legislator and asked Facebook’s Director Shivnath Thukral to have two political posters with Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman’s photograph shared by BJP leader and Delhi MLA Om Prakash Sharma, removed from Facebook.

However, nothing much seems to have come out of the meeting, as companies have found ways to get away with vague information.

These kinds of malpractices threaten the very nature of democracy and become even more dangerous when elections are at stake.

Apar Gupta asserted, “All one-sided information, disinformation, misinformation and non-information equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce when the medium of information is monopolised either by a partisan central authority or by private individuals or oligarchic organisations. When the electronic media is controlled by one central agency or few private agencies of the rich, there is a need to have a central agency, as stated earlier, representing all sections of the society.”

Last week, PM Modi addressed the nation on the Mission Shakti project through social media, using private channels. The speech was later picked up and broadcasted by Doordarshan and the All India Radio. Public announcements of this scale also constitute an MCC violation ahead of the elections.

Speaking to ICF, former IAS Kamal Jaswal said, “Prudence demands and is acted upon in times like these when the MCC is in operation, that government functionary, formally and informally consult the EC when they intend to make this announcement. If the Commission refuses then they refrain from doing so.” He recalled an instance when former PM Manmohan Singh wanted to address public officers but did not go ahead with it following EC’s advice.

One would expect that the EC would be looking sternly into these matters but a shocking revelation came on Friday when the Election Commission announced that Modi’s “Mission Shakti” address did not violate the MCC.

The EC committee, headed by Deputy Election Commissioner in charge of the MCC division, Sandeep Saxena came to the conclusion that Modi’s speech did not violate the guidelines because “he did not mention the BJP, nor did he appeal for votes” in the duration of his address.

What is undeniable in all this is that the BJP has recourse to a devious way of doing things. It does not matter if the official media has picked up the feed from the private agencies because the outcome will still be the same. The laws are fixed in time, while the landscapes have changed, and the BJP has taken advantage of all the factions by resorting to subterfuge.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural forum