The statistics presented to the 144th Academic Council expose the admission exercise for the research programmes of the university (M.Phil./PhD (JRF/non-JRF), M.Tech, and PhD) for the academic year 2017-18 to be a complete failure. The full report of JNUTA’s exhaustive analysis of these statistics can be found here.

This post shares a summary of this report and the implications that this has for future admissions to the research programmes of the university.

1. Intake not Offered

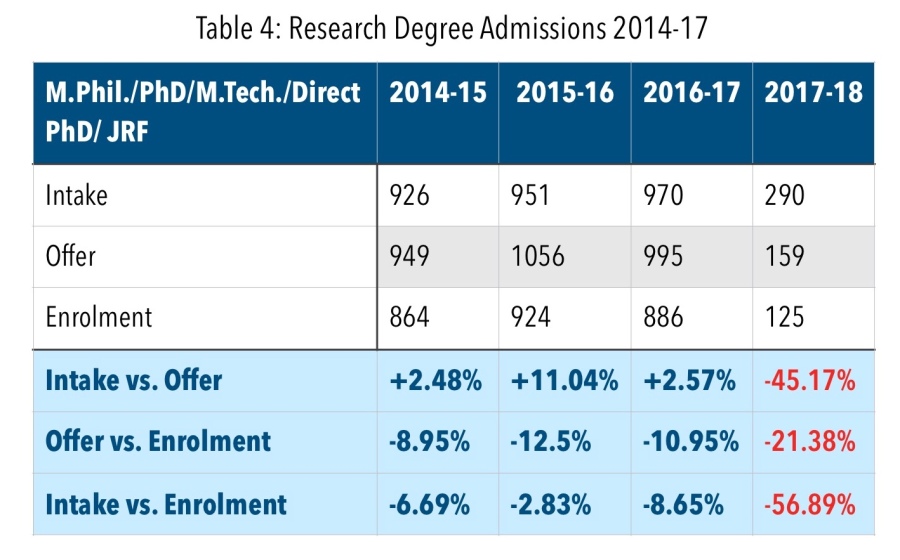

Only 159 seats of the meagre 290 seats announced as intake were offered for admission. 131 seats were not even offered, making offers of just 54.8% of the intake.

This picture is by no means the normal state of affairs for JNU admissions, where offers exceed intake, and the shortfall in enrolment is always under 10%.

2. Failure to Reserve

Clauses 5.2.3 and 5.3 of the 2016 UGC Regulations clearly require institutions of higher education to “adhere to the National/State-level reservation policy”. By slashing the intake to below the 2006 figure+54%, JNU had already violated the Central Educational Institutions (Reservation in Admission) Act, 2006, and things have only gotten worse.

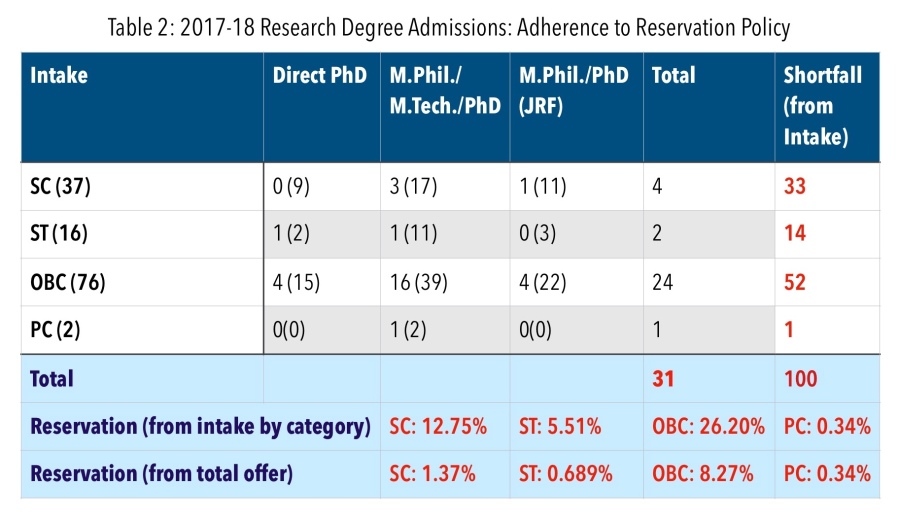

Of the 159 seats offered, only 31 seats were reserved—reservation is therefore just 20.75%, in complete violation of the CEI Act and Constitutional provisions. Not one reservation quota has been filled. Shockingly, the bulk (76.33%) of the 131 seats that were NOT offered (100 seats) are the reserved seats.

In reply to an RTI query, JNU provided the scheme by which reservations were implemented. The formula used was:

- No reserved seats for a programme of study if its intake is below 2 seats.

- No SC/ST/PH reservation for a programme of study if its intake is below 4 seats.

- No ST/PH reserved seats for a programme of study if its intake is below 7 seats.

- No PH reserved seats for a programme of study if its intake is below 17 seats.

However, far from employing this formula, SC/ST/OBC/PC reservations have touched abysmal levels. Programmes with a small intake have no reservation at all. Out of 42 programmes of study advertised, only 3 programmes have SC reservations, 2 programmes each have ST and PC reservations, and only 15 have OBC. Moreover, the JNU administration has converted 19 reserved seats to unreserved ones.

Although non-fulfilment of reservation in terms of admissions offers has been an established trend in JNU, this degree of shortfall in the number of seats offered under the reserved categories is unprecedented.

3. The impact of the withdrawal of deprivation points

Tables 9 and 10 illustrate the striking deviation from past trends in terms of admissions that have a majority rural, low/lower income character.

The reasons for this sharp fall on both parameters is the withdrawal of deprivation points. This same provision has also been crucial in promoting the all-India character of the JNU admissions, which has also taken a severe hit, as Table 11 shows. Post 2011, the trend has been one in which about slightly more than half the new students enrolled are from four major states — Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi and West Bengal; with UP and Bihar vying with each other for the top spot. Deprivation points have a very important role in ensuring that there isn’t an overwhelming dominance of Delhi and other metros in admissions in preventing these four states from taking up the largest chunk of the admissions. In 2017-18 however, Bihar has slipped down to the 4th spot with just 7 admissions into the research programmes.

4. The Implications for future research admissions: A bumpy ride downhill

The outlook for the 2018-19 admissions, and indeed future admissions beyond that, is pretty bleak, should this admission policy not change:

- The negative gap between offers and intake is likely to be maintained, as the 50% cut-off for the written, and the 100% weightage to the viva voce, and the denial of relaxations in marks for SC/ST/OBC/PC will continue to sharply restrict the pool of candidates who make it through to the viva.

- If the present policy on allocation of reserved seats continues, a similar shortfall will inevitably result in meeting the CEI Act and Constitutional obligations. And without the deprivation points to balance the social, economic, and regional provenance of students admitted, JNU shall rapidly slide towards becoming a university for Delhi, a few places nearby and the other metros.,

- Although it may appear from the 2017-18 admissions that intake is on the rise from 2018-19 onwards, this is not true. In fact, the JNU VC’s admission policy has actually ensured that JNU shall next see a figure of these proportions once every five years or so, as that is the time span that an M.Phil./PhD student that the administration has assumed her to have. In the lean years, where intake shall be in 1s and 2s, arguments for admitting students at all will grow weaker; in fact, one can expect that the current practice of conducting the JNUEE in 52 centres will come to be looked at in askance. There will be many more cases like that of Srinagar — a a Centre for the 2018-19 admissions which has been cancelled just a few days before the JNUEE for 2018-19 was to be held there (allegedly because the Kendriya Vidyalaya school system just realised that it is winter in Srinagar!).

- The VC’s 2018-19 Prospectus makes students who have completed a Masters degree eligible for the Direct PhD programme (in a perverse reading of the UGC Regulations 2016’s minimum standards as setting the maximum). This lowering of eligibility has the potential to lead to a fall in offers in the PhD programme, as it cannot be expected that the number of students that they will be able to write a PhD level research proposal fresh out of their MA degree exams.

These dire predictions are however only based on the worrisome trends that the statistics reveal, and has not yet factored in the rank illegality that the JNU VC and his team have become notorious for. Dictatorial measures such as the illegal delinking of the M.Phil./PhD integrated programme unilaterally announced by the Vice-Chancellor too have to be factored in. Which other administration would, based on the whims of one man, wind up a long-standing 50-year-old programme of study instituted by the Academic Council through by a single line duplicitously placed as the final instruction on the admit card? Which other one could institute an entirely new programme in the space of that very line, one that was not even proposed to, let alone approved by, the Academic Council (the sole body that empowered to take these decisions)? Which other would blithely attempt to carry out admissions to a programme that has no intake specified in the prospectus (specially when intake for a stand-alone M.Phil. programme could actually be much higher for many Centres)? Could the answer to all these questions be the same — the only administration that could do this would be one headed by a VC extremely keen on creating enough hostel rooms for the ONE new programme that he truly cares about?

On behalf of all JNU teachers, JNUTA rejects this no-admission policy that is leading to not only a colossal waste of public money but also dashing the hopes of thousands of students. JNU teachers have had no part in this admissions catastrophe that has been brought upon the university despite all their warnings, and will spare no efforts to hold the JNU VC accountable for his wilful violation of the Constitution of India and the Acts its Parliament has enacted. It appeals to the public at large, educationists, Parliamentarians, as well as applicants to join the JNUTA in this battle, because such a cavalier and waste of public money and contemptuous disregard for national policy cannot ever be condoned.