The growing ill-educated pool in our country despite being literate, alert us. There is no complete solution to heinous crimes like mob violence unless inclusive efforts are invested.

On July 17, 2018, a three-judge bench led by CJI Dipak Misra, agreed that it was an obligation of the state to protect citizens and maintain the pluralistic social fabric of the nation against lynching. The court asked the government to see the judgement as a clarion call in a time of exigency and also to file compliance reports within next four weeks. The judgment came in a contempt petition filed by activist Tehseen Poonawalla against continued mob violence by cow vigilantes.

Senior advocate Indira Jaising argued that the incidents of lynchings go “beyond the description of law and order… these crimes have a pattern and a motive. For instance, all these instances happen on highways. This court had asked the states to patrol the highways.” Vrinda Grover, a Delhi based human rights activist commented, “India doesn’t need new laws to curb crimes as mob violence; the enforcement of existing laws is needed.” Her opinion was also shared by senior advocate Colin Gonsalves. “Provisions in the criminal laws are very comprehensive and good,” he agreed. “They just need implementation.”

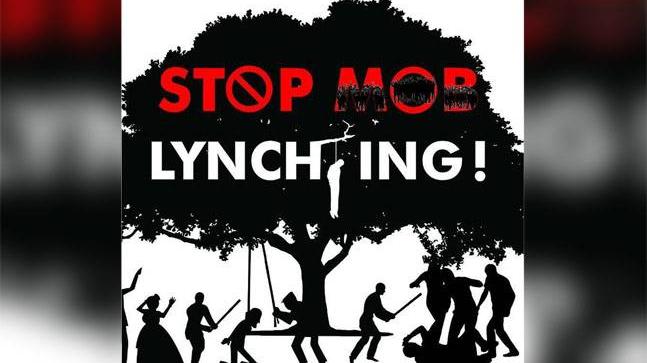

By enacting a special law against lynching, India will become the first country to do so. Supreme Court’s order is undoubtedly appreciable but heinous crimes like mob violence themselves bear many twisted knots. The connotations associated with mob violence are deeper than they appear and it becomes important to reflect on some unavoidable missing loops at this stage of the debate. From the Google engineer’s lynching to Akhlaq’s murder, from Bidar-Karnataka to Dadri-Uttar Pradesh, from WhatsApp rumours to cow vigilantism, the face of intolerance is evident and it was necessary to create some sense of fear in the perpetrators. The law against lynching, if enacted, may help in warning them but it is something ingrained in our society which can only be removed by appropriate interventions.

Last year’s rallies under the phrase #NotInMyName still remain fresh. Earlier this year, the lynching of a tribal in Kerala on suspicion of rice theft enunciated the difference between literacy and education. A few days ago, a Google engineer was beaten to death in Bidar, Karnataka by a 2,000-strong mob in an attack sparked by false social media messages on the claim of kidnapping children in India. A man was lynched yesterday in Rajasthan’s Alwar on the suspicion of cow smuggling. These incidents highlight a wide spectrum of an apparently simple term but they must be questioned, investigated and addressed through a consensus.

The psychology being a scientific realm may help us understand a deep-rooted social violence. Among many theories, socialisation theories of crime stand strong in socially engaged communities like India’s suburban and rural areas. Learning theories such as classical conditioning, operant conditioning and observational learning tell us how a mob mentality functions. Social theories ascertain that criminal behaviour is a learned behaviour and people learn criminal activity from close others, such as family, peers, or co-workers. Criminologist Edwin Sutherland’s differential association theory explains how criminal values could be culturally transmitted to individuals from their significant others.

It is evident that cow vigilantism is not a result of natural tendency. This bears affiliation with a religious vendetta and is strongly backed by Sutherland’s theory. ‘Monkey see, monkey do’- a famous American saying can easily be related with recent episodes of mob violence on suspicions of kidnapping, supported by observational learning theory. Trained and paid rioters supplied with arms and ammunition, have attacked innocents in past. Gujarat 2002 pogrom marks operant conditioning, the third kind of learning theory. This context is very close to the Skinner Box experiment, which was developed by American psychologist B.F Skinner, in which he trained rats to press levers in order to get to their food.

As far as lynching fuelled by religious vendetta has been studied, it is found to be associated with a social facet. Recently, #TalkToAMuslim hashtag has emerged as a patronising action to fight the rising Islamophobia in India. This not only accentuated the rising gap between two major religions and certainly threatened Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb of Hindu-Muslim fusion. The recent Netflix show ‘Sacred Games’ compared the Hindu-Muslim division with Atapi-Vatapi, characters related to Hindu mythology. The show outlines how a soft and tolerant element as religion can be used to create havoc.

Disturbed Areas Act in Gujarat has emerged as a tool to discriminate against Muslims. The law prevents an adherent of one religion from selling/buying a property to/from an adherent of another religion in areas notified under the Act. The rationale given by the state government was for protecting people from being forcibly evicted by members of other religions under the shade of this law. Against the rationale given by BJP government, Vishwa Hindu Parishad leader Pravin Togadia in a speech in 2014 at Bhavnagar, Gujarat, he had suggested spitting on a Muslim man and throwing tomatoes at him. This, while attending to a complaint reportedly about a Muslim man who had bought a property in a ‘Hindu area.’

Evoking the Disturbed Area Act in his speech, Togadia had stated, “This is a long-time conspiracy that Muslims have been executing in cities and villages of India. How can we stop this? There are two ways – one, to impose Disturbed Areas Act everywhere, two – consult a lawyer, barge into a house, occupy it forcefully and hang the board of Bajrang Dal. We can handle a case later.” His audience had cheered his hatred against Muslims. The chasm created between young generations of two communities is starkly evident in Gujarat. If this difference and distance between the two groups remain, the hate is not going anywhere anytime soon.

In addition to the psychological and social aspects of the turmoil, the educational conscience of a criminal also constitutes the loop. The value-based education is mostly inexistent in India’s education system. The Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) pattern brought by previous governments to develop cultural and social values among students and to extirpate the evolving ill mentality, was abolished by the BJP government. So, what else could be a methodology as an educational intervention to curb the growing hatred among young Indians if it not CCE? The current government fails to bring new educational framework tackling these unavoidable subjects of concern.

I wouldn’t add that the incumbent political party and its sympathisers are basic reasons behind mob savagery but irony too felt anxiety when union minister Jayant Sinha garlanded mob lynching convicts adding that he was ‘honouring the law.’ On the same day of SC’s directive on lynching, Swami Agnivesh was marginally saved from being lynched by members and sympathisers of the same party which was directed to take concrete steps on the same mob violence.

Following this, Ramchandra Guha tweeted:

Swami Agnivesh is known for his work to emancipate bonded labour, and for the promotion of inter-faith harmony. He also has a sense of fun, with a joyous laugh. A Hindu monk of courage, compassion, and humour; so naturally he must be beaten up in Modi’s India.

The criminal milieu and its foster care in India lug the political overtone. Political interference in enforcement bodies remains unavoidable in a big democracy like ours. The growing ill-educated pool in our country despite being literate alerts us, and there is no complete solution to heinous crimes like mob lynching unless inclusive efforts are invested.

[Author is a research scholar at The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. He serves as an Editor to Academia.edu & WikiProject.]