The archaeological evidence shows that the first ever city—Harappa– was built in the Indian Sub-continent around 2850-2900 Before Christ in the world. The name Harappa sounds like a South Indian divine man’s name among agrarian and cattle herding communities. For example, Mallappa, Beerappa, Veerappa are very famous names in South India. In Kannada and Telugu regions the names that end up with “Appa” are very popular among the Shudra and Dalit communities. Names like Mallappa and Beerappa are now divine names of God-Heads that have cattle rearing and agrarian community life.

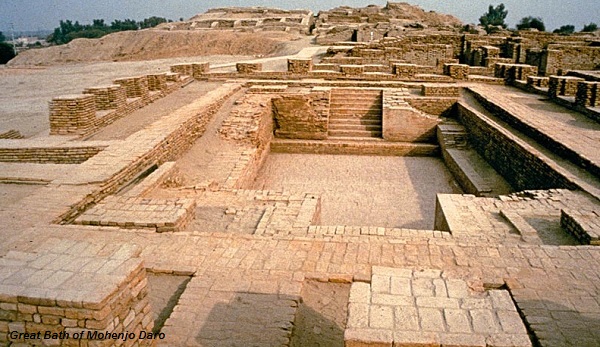

The Harappa city was built on the bank of the Indus river, which is in present Pakistan after the partition of India. But it represents the whole human history of building civilization and culture. It represents the civilization of advancing animal economy, constructing technology of building houses, streets, tanks, canals, and forts almost 1500 years before the first Indian spiritual book Rigveda was composed or written.

The Indological and archeological studies also established that this civilization was built by Indo-Africans before the Aryan race had shown its traces in the Indian Sub-continent. The contemporary Indian village and cultural transformation shows that without there being villages, urbanization of the society does not take place. All kinds of local experiments take place in the realms of cattle economy, agriculture and technology building and management. This has seen happening during my life time too and that could be the course of history of emergence of the city of Harappa also. No city emerges without villages all around.

There is a civilizational culture in Indian sub-continent to build villages and cities in the name of persons. For example, my village name is Papaiah Pet. Older generations than that of mine told us that one fisher man called Papaiah with a family name Uppari and my grandmother Lingamma with a family name Kancha ( who was a shepherd widow) built their first round of thatched houses and gradually that village of fishermen/women, shepherds, toddy tappers came into being. Gradually by my mother and father’s generation along with shepherds and fishermen/women , toddy tappers (as the surroundings of the village had hundreds of palm trees), tillers of land by using buffalo and bullocks settled down and expanded the village. Over a period of time along with the main village population the Lambada tribes, whose main occupation was cattle rearing settled down. By now the village has a population of 4500 people. It is a major Panchayat. For the last 10-15 years reverse migration from the village to urban areas is taking place.

Similarly, the city of Harappa could have been built by the early villagers that got transformed into urban dwelling with a man’s name called Harappa. Building the city of Harappa would have been impossible without several villages surrounding that city. In the Indus valley region several villages would have emerged much before the city of Harappa was built. Unless there was some sort of agrarian economic development, building a city is impossible.

For example, in my childhood building a house in my village was done without the use of any carpenting tools. The natural wood logs were used for building a thatched house and I could see over a period of time carpenters emerging from the same village population with a skill of crafting wood in a sophisticated manner. Most of the walls of the houses would be of mud prepared by the family labor and skill. Gradually, there emerged brick makers for building brick wall houses. Though pot making was already there, before my eyes more sophisticated pot makers emerged with diversified skills. When I was a child, tilling the land with buffalo or bull drawing plough was common. The technology of plough was very underdeveloped, therefore, the animals and the human beings who were handling the plough would suffer a lot. But I have seen the village carpenters becoming more and more skilled and improving the plough in shape and size. Meanwhile, similar changes also occurred in the skill domain of ironsmiths, and so on. For example, in my childhood I used to cry a lot when the barber was shaving my head, as the knife which was very hard and the skills of the barber used to be very underdeveloped. Gradually, that situation changed quite fast. The knife became sharper because of the advanced ironsmithing skills of the smith and also improvement in the shaving skills of the barber. I saw such changes in every sphere of life within the village economy. I also saw how these technological advancements and skill improvements shifted to nearby towns and the process of urbanization taking place in a gradual manner.

The studies on Harappa show that urban civilization was far more developed than the one I saw in my childhood in the town where I studied for my high school graduation called Narsampet. It also has shown the signs of class formation, which was of course a common phenomenon, both in the villages and urban areas. Class formation is an advanced stage of an economy. The Harappan city could have been built in socioeconomic conditions that existed in my life time.

The city civilization did not confine to one small place. It was wide spread. That was the reason why cities like Mohenjodaro and Dholavira came into existence in faraway places. That also indicates that the village economy was very wide spread in the Sindhu region. Quite interestingly we do not see any signs of such civilization developing in the Ganga region. We do not even know that if there were villages in Ganga region by the time city of Harappa was built. Why? The answer to this question needs to be searched in what is known as Vedic economy in subsequent years. The Vedic economy is known as pastoral economy where cattle grazing and surviving on the animal products became the main stay. That in essence means the Vedic economy and social life became more backward than the Harappan economy. The urbanization disappeared. Even bigger villages do not seem to have existed.

The archeological studies mapped up on genome studies have shown that the Harappan urban civilization was built by Indo-Africans, whose physical characteristics match more with physical charaterisitcs of South Indians who are Dravidians ( The Dravidians are nothing but Indianized mixture of Indo-Africans). The Vedic civilization, culture and linguistic society was built by Indo-Aryans, whose migration seems to have taken place from middle east ( mainly from the present day Iran). This civilization is said to have survived during 1500 to 1100 BC.

Historically this civilization is also known as the one which followed the Harappan civilization. As there is not much archeological evidence on this civilization the earliest and most authentic evidence for this civilization comes from the Rigveda, the first Brahminic scripture of India. The roots for the Indian caste system are seen in this text. It was composed in the Indo-Aryan language, Sanskrit, which is even today the main property of the Indian Brahmins, as the priests in Hindu temples. They alone read, recite and interpret even in the 21 century all the Sanskrit texts. No Shudra (who constitute about 60 per cent of the so called Hindu population) have the basic right to read or study in the Hindu religious schools, colleges. No Shudra has a right to become the priest in any Hindu temple. No Shudra philosopher emerged from the Hindu Brahminist society from the days of writing of Rigveda to present. Only Brahmin or Kayasth writers are treated as Hindu philosophers. The Buddhist tradition has a different genealogy of thought and philosophy.

After the Hindu fundamentalist party, Bharatiya Janatha Party (BJP) came to power in 1999 and 2014, with complete involvement of the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) , Shudras have become the main drivers of this fundamentalist ideology. The anti- minority campaign was carried with support of Shudra muscle power. But no Shudra is allowed to become the priest and philosopher in India. Most rich temples like Thirupathi (Andhra Pradesh) Jagnnada (Orissa) and Vishna Devi (Jammu) Ayodhya Srirama temple (Uttar Pradesh) Srikrishna temple Madhura (Uttar Pradesh) and Guruvayyur (Kerala) will not allow a Shudra to become a priest. The monopoly to read, recite and interpret all Vedas still remains with one small caste, Brahmin. The RSS is also headed mostly by Brahmins with the authority that they are Veda pundits. The RSS which uses the Shudra (OBC) votes and muscle power for the advantage of Brahminism but never fought for their equal rights in the spiritual system. The Shudras have their historical roots in Harappan civilization as most Shudras have their genetic heritage from the Harappan Indo-Africans. In other words the Harappan civilization and productive and artisanal culture was theirs. It is quite obvious that there were no Brahmins, Brahminism and Sankrit culture during Harappan times.

It is not known how the Harappa civilization, including its cities disappeared and how the whole civilization was taken back to pastoralism after the Aryan Brahminism became hegemonic. As I said earlier in the Vedic pastoralist economy, well developed villages are not mentioned—leave alone Harappa type cities.

Vedic Brahminism tells that its pastoralism slowly transformed into agrarian economy in a period of 1000 years. However, a careful reading of the Rigvedic hymens shows that the scripture quite surprisingly does not invoke God but it invokes Agni (Fire) as the most worshippable force. The first hymn reads as follows:

[01-001] HYMN I. Agni.

1 I Laud Agni, the chosen Priest, God, minister of sacrifice, The hotar, lavishest of wealth.

2 Worthy is Agni to be praised by living as by ancient seers. He shall bring hitherward the Gods.

3 Through Agni man obtaineth wealth, yea, plenty waxing day by day, Most rich in heroes, glorious.

4 Agni, the perfect sacrifice which thou encompassest about Verily goeth to the Gods.

5 May Agni, sapient-minded Priest, truthful, most gloriously great, The God, come hither with the Gods.

6 Whatever blessing, Agni, thou wilt grant unto thy worshipper, That, Angiras, is indeed thy truth.

7 To thee, dispeller of the night, O Agni, day by day with prayer Bringing thee reverence, we come

8 Ruler of sacrifices, guard of Law eternal, radiant One, Increasing in thine own abode.

9 Be to us easy of approach, even as a father to his son: Agni, be with us for our weal.

In those times Agni could not have been seen as an agent of cooking but could have been seen as the most powerful agent of burning the enemy’s resources—houses, cattle, crops, grain and other resources of livelihood. The next major worshipping agent in Rigveda was Vayu ( Air). The Air ( or Wind) was an aid of Agni in the process of destruction.

When I was just 3-4 years old child my entire village—Papaiah Pet Chenna rao Pet Mandal, Warangal District– got burnt down. In the revenue records of the village this was a land mark event. The terrifying stories of how Agni destroyed the village and the blowing Vayu was helping it carry the fire from one end of the village to the other end were told and retold as a terror narrative by the eyewitnesses. Those houses that were not on the wind’s way were safe. But most of them got burnt down to ashes ,including my house. The villagers used to abuse the Agni Devudu (God Fire) and Vayu Devudu (The God wind) for burning and for spreading that destruction from house to house, for several decades. That Agni destroyed our houses, some of the cattle, grain and few people who got trapped were burnt to ashes. Not even their bones could be seen.

The fire started in the Westward of the village in a small hut with cooking hearth accident, as the thatched house had very low roof. For all those village masses the Agni and Vayu were never positive and helpful Gods but destructive Gods who came to destroy their village. No doubt both those elements are useful and they know that. They were called Devudu (God) no doubt as the Rigveda writers did. In the village discourses Fire god not referred to creation but only referred to destruction.

Imagine for a moment, if an enemy had planned that destruction, for that person Agni and Vayu which gutted the whole village and turned it into ashes become the positive Gods who caused his/her victory.

In the Rigveda Agni and Vayu find more place than Brahma or Indra. In fact Agni, Vayu, Indra and Horse (as a worship animal) find more place than God in any descriptive sense in Rigveda. Why this? No ancient spiritual text in the world places Agni and Vayu in the place of God or above God? The notion of God is highly philosophical where the Agni and Vayu are tangible materials. There is hardly any scope for philosophizing the tangible materials like Agni and Vayu as with the notion of God.

The notion of God is more than anything else deals with creation. Destruction is not central to God. Of course, God could be imagined as force of punishment for wrong doing with a view of reform or rectification. Agni has no such nature and character.

One established historical fact is that the cities of Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and Dholavira are great cities of life and civilization. There was lot of science and technology, involved, in building those cities. There is no indication in Rigvedic texts which worshipped a burning materialist agency like Agni but not God of creative nature that it were those forces which destroyed that civilization.

Does it not indicate that the writers of Rigveda themselves believed in destruction but not in construction of civilizations? Does it not lead to the conclusion that it were these forces that constructed caste theory in the same text that Shudras who do agrarian tasks, cattle grazing, carpenting, smithing of bronze and iron, pot and brick making should be treated less than human beings and priests (Braahmins) who perform rituals should be treated as Bhoodevtas (Gods on earth).

(An abridged version of this article was published in Daily O on 19/08/2018 with a title “Shudras, Not Aryans, built the Indus Valley Civilization)

Prof. Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is Director, Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy, Maulana Azad National Urdu University

This article was first published on countercurrents.org.