Director Martin Doblmeier’s new documentary, “Backs Against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story,” is scheduled for release on public television in February. Thurman played an important role in the civil rights struggle as a key mentor to many leaders of the movement, including Martin Luther King Jr., among others.

I have been a scholar of Howard Thurman and Martin Luther King Jr. for over 30 years and I serve as the editor of Thurman’s papers. Thurman’s influence on King Jr. was critical in shaping the civil rights struggle as a nonviolent movement. Thurman was deeply influenced by how Gandhi used nonviolence in India’s struggle for independence from British rule.

Visit to India

Born in 1899, Howard Washington Thurman was raised by his formerly enslaved grandmother. He grew up to be an ordained Baptist minister and a leading religious figure of 20th-century America.

Journey of the delegation in South Asia. Marc Korpus, CC BY

In 1936 Thurman led a four-member delegation to India, Burma (Myanmar), and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), known as the “pilgrimage of friendship.” It was during this visit that he would meet Mahatma Gandhi, who at the time was leading a nonviolent struggle of independence from British rule.

The delegation had been sponsored by the Student Christian Movement in India who wanted to explore the political connections between the oppression of blacks in the United States and the freedom struggles of the people of India.

The general secretary of the Indian Student Christian Movement, A. Ralla Ram, had argued for inviting a “Negro” delegation. He said that “since Christianity in India is the ‘oppressor’s’ religion, there would be a unique value in having representatives of another oppressed group speak on the validity and contribution of Christianity.”

Between October 1935 to April 1936, Thurman gave at least 135 lectures in over 50 cities, to a variety of audiences and important Indian leaders, including the Bengali poet and Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, who also played a key role in India’s independence movement.

Throughout the journey, the issue of segregation within the Christian church and its inability to address color consciousness, a social and political system based upon discrimination against blacks and other nonwhite people, was raised by many of the people he met.

Thurman and Gandhi

The delegation met with Gandhi towards the end of their tour in Bardoli, a small town in India’s western state of Gujarat.

Gandhi, an admirer of Booker T. Washington, the prominent African-American educator, was no stranger to the struggles of African-Americans. He had been in correspondence with prominent black leaders before the meeting with the delegation.

As early as May 1, 1929, Gandhi had written a “Message to the American Negro” addressed to W.E.B. DuBois to be published in “The Crisis.” Founded in 1910 by DuBois, “The Crisis” was the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Gandhi’s message stated,

“Let not the 12 million Negroes be ashamed of the fact that they are the grandchildren of slaves. There is no dishonour in being slaves. There is dishonour in being slave-owners. But let us not think of honour or dishonour in connection with the past. Let us realise that the future is with those who would be truthful, pure and loving.”

Understanding the idea of nonviolence

In a conversation lasting about three hours, published in The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Gandhi engaged his guests with questions about racial segregation, lynching, African-American history, and religion. Gandhi was puzzled as to why African-Americans adopted the religion of their masters, Christianity.

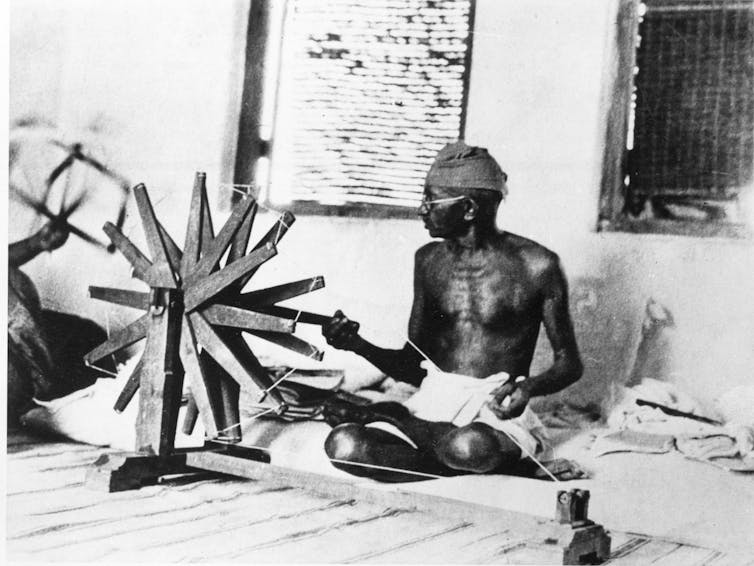

Gandhi, spinning cotton, in a photo from 1931. AP Photo

He reasoned that at least in religions like Islam, all were considered equal. Gandhi declared, “For the moment a slave accepts Islam he obtains equality with his master, and there are several instances of this in history.” But he did not think that was true for Christianity. Thurman asked what was the greatest obstacle to Christianity in India. Gandhi replied that Christianity as practiced and identified with Western culture and colonialism was the greatest enemy to Jesus Christ in India.

The delegation used the limited time that was left to interrogate Gandhi on matters of “ahimsa,” or nonviolence, and his perspective on the struggle of African-Americans in the United States.

According to Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s personal secretary, Thurman was fascinated with the discussion on the redemptive power of ahimsa in a life committed to the practice of nonviolent resistance.

Gandhi explained that though ahimsa is technically defined as “non-injury” or “nonviolence,” it is not a negative force, rather it is a force “more positive than electricity and more powerful than even ether.”

In its most practical terms, it is love that is “self-acting,” but even more – and when embodied by a single individual, it bears a force more powerful than hate and violence and can transform the world.

Towards the end of the meeting, Gandhi proclaimed, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

Search for an American Gandhi

Indeed, Gandhi’s views would leave a deep impression on Thurman’s own interpretation of nonviolence. They would later be influential in developing Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance. It would go on to shape the thinking of a generation of civil rights activists.

In his book, “Jesus and the Disinherited,” Thurman addresses the negative forces of fear, deception and hatred as forms of violence that ensnare and entrap the oppressed. But he also counsels that through love and the willingness to nonviolently engage the adversary, the committed individual creates the possibility of community.

As he explains, the act of love as redemptive suffering is not contingent on the other’s response. Love, rather, is unsolicited and self-giving. It transcends merit and demerit. It simply loves.

A growing number of African-American leaders closely followed Gandhi’s campaigns of “satyagraha,” or what he termed as nonresistance to evil against British colonialism. Black newspapers and magazines announced the need for an “American Gandhi.”

Upon his return, some African-American leaders thought that Howard Thurman would fulfill that role. In 1942, for example, Peter Dana of the Pittsburgh Courier, wrote that Thurman “was one of the few black men in the country around whom a great, conscious movement of Negroes could be built, not unlike the great Indian independence movement.”

King, love and nonviolence

Thurman, however, chose a less direct path as an interpreter of nonviolence and a resource for activists who were on the front lines of the struggle. As he wrote,

“It was my conviction and determination that the church would be a resource for activists – a mission fundamentally perceived. To me it was important that the individual who was in the thick of the struggle for social change would be able to find renewal and fresh courage in the spiritual resources of the church. There must be provided a place, a moment, when a person could declare, I choose.”

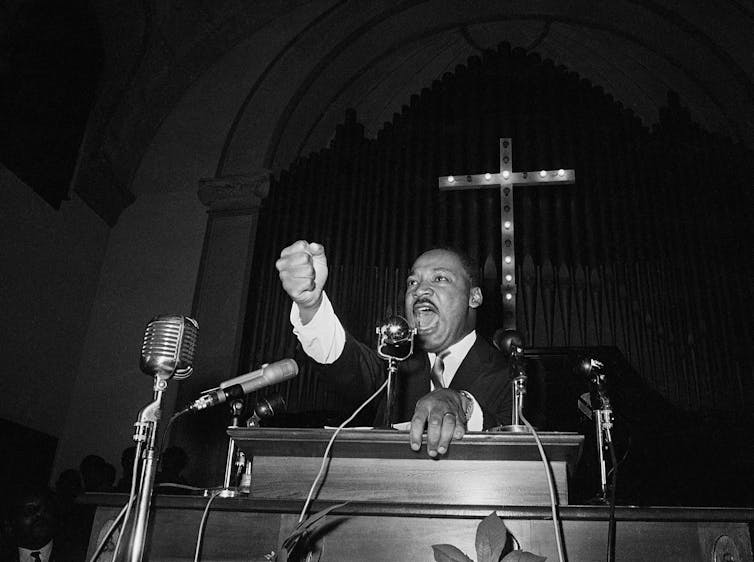

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., speaking at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta. AP Photo

Indeed, leaders like Martin Luther King did choose to live out the gospel of peace, justice and love that Thurman so eloquently proclaimed in writing and the spoken word, even though it came with an exacting price.

In his last letter to Martin Luther King, dated May 13, 1966, Thurman expressed his regret for the time that had elapsed since he and King last spoke. He ended the short note with a rather foreboding quote from the American naturalist and essayist Loren Eiseley,

“Those as hunts treasure must go alone, at night, and when they find it they have to leave a little of their blood behind them.”

King, like Gandhi 70 years ago, fell to an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.