Thiruvananthapuram, Pathanamthitta, Ernakulam, Alappuzha (Kerala): Around 2.30 am on August 15, 2018, Abey Sushan, the programme manager of the National Health Mission for Pathanamthitta district, got an SOS call from the local administration. Flood waters had entered the taluk hospital in Ranni town and were rising so fast they threatened the safety of inpatients.

Volunteers like Jasmine Paulfin (left) and Sajitha (extreme right) helped ensure chlorination of wells and inform residents about consuming doxycycline tablets during their house visits. Reethamma CA (centre) is a junior health inspector.

Three pregnant women had gone into labour at the hospital which also had 25 bedridden patients. Pathanamthitta was one of the one worst affected districts in the floods that devastated Kerala in August 2018, leaving an estimated 5 million people displaced.

Sushan had to arrange for the immediate evacuation of the three women and their transfer to the Pathanamthitta general hospital. “Luckily we were able to summon ambulances,” he said. A contingency plan was drawn up for the evacuation of the other patients in case the waters rose further.

This was just one of the many medical crises averted by quick thinking and action by state health authorities in Kerala. A deluge on this scale usually brings with it fears of water- and vector-borne epidemics such as cholera, leptospirosis (rat fever), hepatitis A, and malaria. The July 1998 floods in Malda district in West Bengal, for instance, had ended in a cholera epidemic, followed by a diarrhoea outbreak which had left 276 dead.

Besides, Kerala was faced with another potential health crisis post-floods–it has the highest number (5 million) of diabetes and hypertension patients in India. Many chronic patients had been left homeless, without access to their daily, critical dose of medicines. Non communicable diseases (NCDs) have also led to an increase in kidney ailments in Kerala. About 100,000 dialyses are conducted in the state in a year and number of dialysis centres increased six times in the last five years, Mathrubhumi reported on April 29, 2018.

Kerala is known for its robust healthcare system–maternal mortality rate here is 61 deaths per 100,000 live births (India average is 167) and neonatal mortality rate is 6 deaths per 1,000 live births. But the floods had inflicted a loss of nearly Rs 325 crore on its health infrastructure, crippling it.

So how did the state cope? Our investigations found that planned monitoring and surveillance of disease and medical issues at state and district levels helped to minimise deaths and contain an impending crisis. Volunteers played a critical role in this effort as did the state’s determination to bypass red tape at critical points.

“The scale of the disaster was unprecedented,” recalled Rajeev Sadanandan, additional chief secretary, health and family welfare, and the officer credited for containing the Nipah outbreak. “With Nipah we were handling a virus we did not know, which was stressful. Here, we knew what to expect which helped us stay ahead, although the scale was massive.”

The state established a control room in capital city Thiruvananthapuram to coordinate the logistics of providing manpower and medicines statewide. Communicable diseases were to be contained by providing access to clean water and ensuring close monitoring at camps. Health volunteers were to ensure that those with non communicable diseases would be provided medicines, care and monitoring.

Source: Directorate of Health Services (here, here, and here)

Note: Data for 2018 is as of September 2018

In this concluding part of our three-part series (you can read part one here and part two here) of how Kerala is rebuilding itself after the floods, we investigate how the state managed to prevent a major health crisis though eight of its 14 districts were in the ‘heavily affected’ category.

IndiaSpend travelled to four districts, three–Pathanamthitta, Ernakulam,and Alappuzha–of which have been categorised as ‘highly affected districts’ by a DHS report, to understand how the state managed to stave off a health crisis.

How daily monitoring and surveillance worked

It was a little after lunch time at the directorate of health services in Thiruvananthapuram on September 10, 2018. A nationwide hartal (strike) had left the building empty. But on the first floor, a team of more than 60 people, mostly doctors, were hard at work, handling post-flood surveillance and monitoring at the 24×7 disaster control room set up on August 18, 2018.

A review meeting including the nodal officers, minister of health, and senior officials in the health department at the DHS office in Thiruvananthapuram.

At the control room, doctors had been appointed as nodal officers for 10 teams that dealt with public health, drugs and logistics, damage assessment, human resource management, documentation, media surveillance and so on.

“The teams meet in the morning to plan for the day, and again in the evening to review and evaluate,” said Sarita RL, director of health services. “The review meeting in the evening usually has the health minister and the secretary of health who evaluate daily reports.”

During the initial phase, it was imperative that medicines, medical assistance and clean water reached the camps and affected homes as per need. The drugs and logistics management and human resource teams ensured that the scores of doctors and volunteers pouring in from different regions were directed to relevant locations. Stocks of medicines and consumables were maintained at district levels based on local inputs and reports that reached via email by 4 pm each evening.

Rajeev Sadanandan, additional chief secretary, health and family welfare, said that with Nipah the government was handling a virus it did not know. But with the flood, they knew what to expect despite the scale.

In Ernakulam, the district health services set up a control room with five desks including a call centre. (Initially, the call centre was operated from Kollam which was not affected by the floods.) “The calls would be colour-coded based on urgency after screening and volunteer doctors attended calls,” said Asha Vijayan, a nodal officer for the control room.

In the five days to August 22, 2018, the helpline received 4,266 calls of which over 72% were addressed successfully, noted a report accessed by IndiaSpend.

The team also received 3,411 WhatsApp messages. “It was a WhatsApp-managed disaster,” said Sadanandan. There were so many officials from across the country volunteering to help that at one point people were asked to exit a WhatsApp group because it was getting overcrowded, he said.

In addition, a team of doctors from Tamil Nadu provided technical support based on their experience of the 2015 Chennai floods.

There were fears of a leptospirosis outbreak

Preventing an outbreak of leptospirosis or any other water-borne disease was high on the agenda of the health mission. This was because there were high chances that displaced people could come in contact with infected water.

Flooding facilitates the proliferation of rodents which shed large amounts of leptospires (bacteria) in their urine that cause the disease, noted a World Health Organization (WHO) guideline. Outbreaks of leptospirosis had occurred post-floods in Brazil (1983, 1988 and 1996), in Nicaragua (1995), Krasnodar region, Russian Federation (1997), Santa Fe, USA (1998) Orissa, India (1999) and Thailand (2000).

Between August and September 2018, Kerala did report 1,084 cases of leptospirosis, of which 39 proved fatal, and 568 cases of dengue of which two led to deaths, according to provisional data available in the DHS website. But the crisis did not spin out of control.

In Ernakulam, nearly 2.3 million 100 milligram doxycycline tablets–that prevent leptospirosis—were given to flood victims and cleaning volunteers, recalled Shibu Balakrishnan, medical consultant with WHO India. This prophylactic programme for leptospirosis probably ranks as the largest in world, he pointed out.

Ten teams, including medical and non-medical staff, were assigned across the district specifically in highly affected regions around Ranni including Chittar and Seethathode. “We would go to camps in the morning and the afternoon to ensure doxycycline tablets were provided,” said Anil Kumar, a junior health inspector (JHI) in Ranni taluk hospital. “We were constantly in touch with community members we had identified to report on any health related events.”

Patients who visited the taluk hospital were supplied with doxycycline tablets and were instructed to consume it immediately if they had been in contact with water. “We were concerned that people who were returning home to clean their homes could be infected,” said Vaishakh VR at Ranni. “We did not wait for instructions to prescribe the tablets.”

The health team in Ranni taluk hospital including Vaishakh VR and Anil Kumar, junior health inspector, who went to camps to ensure doxycycline tablets and other medical needs were available.

“By the time I got involved in Ernakulam on August 21, the system had handled the challenge well, especially ensuring that water and doxycycline was provided extensively,” said Shibu Balakrishnan, medical consultant with WHO India.

How the volunteer network was put to use

Volunteers played a significant role in the measures to prevent a leptospirosis outbreak. Jasmine Paulfin and Sajitha are members of Kudumbashree, state poverty eradication programme, which played a big role in relief and rehabilitation work, as we reported in the first part of the series. The duo work in Gothuruth in Ernakulam and are a part of Shradhha, a post-disaster monitoring programme devised in the district.

Under the programme, each volunteer–from the same neighborhood–is assigned about 40 homes to monitor cases of leptospirosis and its treatment. “We have been visiting homes to ensure that wells are chlorinated, provide information on rat fever and enquire about doxycycline availability and consumption,” said Paulfin.

They visited the same homes again after three days to repeat the process. “If we find persistent fevers reported in an area, then we focus closely on those cluster of homes,” said Manju KS, medical officer at the primary health clinic (PHC) in Gothruthu.

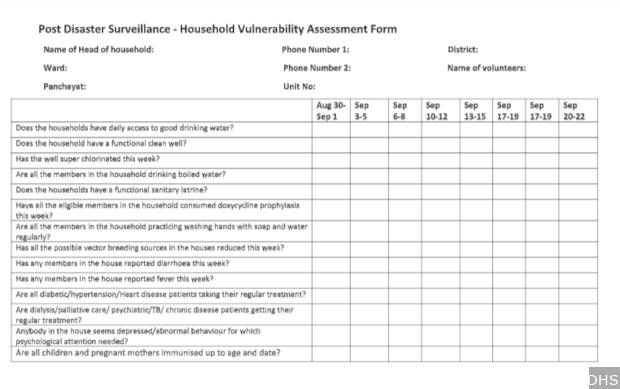

The checklist created for health volunteers to ensure household-level measures and precautions were taken avoid a health epidemic.

“In the initial phase, it was difficult to find volunteers, as everyone including me were affected,” said Reethamma CA, PHC’s junior health inspector. “But a Rs 5 incentive for visiting each house was helpful.”

But communicable diseases weren’t the only challenge for Kerala.

Ensuring insulin, medicines and dialysis for diabetics

Diabetics on insulin therapy were facing a crisis in Pathanamthitta during the floods: Cold storage systems had broken down because power supply had been disrupted. Insulin needs to be in a temperature-controlled environment to prevent protein breakdown that would render it ineffective. Patients identified in camps were given oral hypoglycemic drugs by medical officers. “Although it is not most effective for patients who are severely diabetic, but under the circumstances we had to opt for it,” said Sushan.

Dialysis was another critical area of patient care crippled by power breakdown. Patients were identified at camps by staff like JHI, junior public health inspector (JPHI), ASHA workers and health volunteers. With a total of 18 dialysis machines in two hospitals, patients were treated in three shifts of six hours each. Purified water needed for dialysis was ensured by the authorities which pressed reverse osmosis equipment.

Treatment was resumed for patients whose medication had been interrupted based on the guidelines provided by the state health department. In Ernakulam, palliative care nurses helped identify people with NCDs like hypertension, kidney ailments, and diabetes.

When technology came in handy

Kuttanad in Alappuzha is located at the lowest altitude in India. A low water table makes it vulnerable to water-borne diseases. “We had used KoBo application [field data collection tool] on mobile phones here earlier to check for communicable diseases,” said Anil Kumar, block medical officer of Veliyanadu. “It helps us locate the homes by geo-tagging and identifying hotspots. We have continued it for post-flood surveillance also.”

They have had a monitoring mechanism where volunteers, mostly women, inform health staff about any health issue in the neighborhood.

In Ernakulam, the health administration used KoBo to report data from private hospitals. Most of the data in the integrated diseases surveillance programme were from government hospitals.

An interdepartmental coordination mechanism was established with the district health officials and private hospitals, said Balakrishnan. “Medical officers were given the responsibility of liaising with private hospitals to report communicable diseases, especially leptospirosis, using the app,” said Balakrishnan of WHO India. They would go through medical records and registers among others to pick any probable cases, and sensitise private practitioners about reporting any suspected cases immediately.

Note: An earlier version of the story showed the chart on cases and deaths due to disease erroneously. We have now corrected this, and we regret the error.

(Paliath is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend