New Delhi: Maharashtra and Karnataka are using decades-old land acquisition laws–similar to a now-defunct colonial-era law–to acquire land for large projects, bypassing a more recent central law that provides for landowners’ consent and fair compensation.

However, the Madras High Court in July 2019 termed a similar law in Tamil Nadu “null and void”, putting a question mark on all three states’ practices, and giving activists a chance to challenge the states in court.

The three states have used these outdated laws since 2014, instead of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act enacted by the central government in 2013. Such state laws should have been repealed or brought in line with the LARR Act, experts said. For the states to continue to use them, they would have to be re-enacted, the Madras High Court order stated.

The LARR Act of 2013 replaced the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894. The new law enhanced compensation for landowners, made landowners’ consent mandatory before their land was acquired, and required projects to first study the social impact of land acquisition.

But even after this, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Karnataka continued to use their respective laws–which were based on the 1894 colonial law–to acquire land for high-profile projects including the world’s largest oil refinery in Maharashtra, the Chennai Metro Rail project and an industrial corridor in Karnataka.

On July 3, 2019, the Madras High Court struck down Tamil Nadu’s use of its land acquisition laws, holding that these laws became invalid the day the LARR Act was passed. The court cancelled all land acquisition carried out under these laws since 2014, except where the land had already been put to use.

This has called into question the continued use of old state laws in Maharashtra, where it has been unchallenged so far, and Karnataka, where a case is pending before the state high court.

Tamil Nadu had defended its use of state laws in the High Court saying that it had the approval of the President. The High Court rejected this argument. The Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation, the state body that acquires land for industries, made a similar claim in response to our queries. The Karnataka officials did not respond to the specific query on why the old state laws are being used instead of the LARR Act to acquire land for industries.

After the LARR Act came into force in 2013, states such as Gujarat, Jharkhand, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh enacted amended versions of the law or brought in new rules to bypass its provisions. These dilutions were widely reported and led to protests and demonstrations. But the use of outdated laws by Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Karnataka to bypass LARR Act, 2013, has escaped public scrutiny so far.

“Most states diluted the 2013 Act to do away with some requirements,” said Suhrith Parthasarathy, a Chennai-based lawyer who represented some of the petitioners in Tamil Nadu. “This is not condonable, but what these three states did is even worse–they said the 2013 law won’t apply at all.”

The decisions were taken by state governments ruled by political parties across the spectrum: Maharashtra has a Bharatiya Janata Party government; the Tamil Nadu government is led by the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam; and the Karnataka government that took the decisions in question was led by the Congress, which also led the United Progressive Alliance government at the Centre when the LARR Act was passed in 2013.

The old state laws

Land acquisition is on the “concurrent list” of the Indian Constitution: That is, states can make their own laws on land acquisition. Maharashtra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu used these powers to introduce laws to acquire land for specific purposes such as industries or highways.

The Karnataka Industrial Areas Development (KIAD) Act of 1966 empowered the state government to declare any piece of land an industrial area and acquire it, whether or not the owners wanted to give it. Compensation was to be decided through negotiations between the government and landowners, and in case they could not agree, the Act referred to procedures under the 1894 Act to calculate compensation.

The Maharashtra Industrial Development Act, 1961, and Tamil Nadu Land for Industrial Purposes Act, 1997, carried similar provisions.

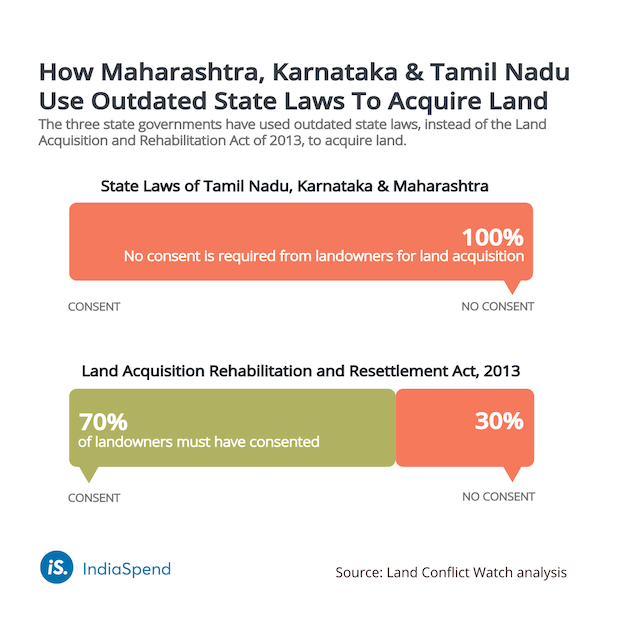

In contrast, the LARR Act requires, as we said, the consent of at least 70% of the affected people in case the land is required by a private firm or for a public-private project. It makes non-landowners such as sharecroppers and farm workers eligible for compensation and rehabilitation, and carries special provisions for Dalit and Adivasi families.

The state laws have none of these provisions.

After the LARR Act was passed, states should have amended their “very old” laws to bring them in line with the LARR Act’s progressive principles, Himanshu Upadhyaya, faculty at the School of Development at the Azim Premji University, told IndiaSpend. “But it was never done.”

Instead, states did the opposite: They made the state laws exempt from the LARR Act.

Amendments to LARR Act

In February 2014, just one month after the LARR Act came into force, Tamil Nadu passed an amendment to the law as it applied within the state. The amendment inserted a new clause, Section 105A, which said that provisions of the LARR Act “would not apply” to three state laws that govern land acquisition–for industries, highways and for land for redistribution to Dalits.

The President approved the amendment on January 1, 2015.

These laws were then used to acquire land for highways–for instance, paddy fields and orchards for a bridge in Tiruchirapalli district–and even to take over houses and school grounds in Chennai for the second phase of the city’s metro rail project.

Acquisition under the three state land laws accounts for three-fourths of all land acquisition in Tamil Nadu, according to a 2019 study by the Centre for Science and Environment, a think-tank based in New Delhi.

These acquisitions were met with resistance. By 2018, nearly 150 petitions were filed before the Madras High Court asking for the state’s LARR Act amendment to be struck down. The petitioners included people from “all walks of life”–from farmers affected by an industrial area to city dwellers in Chennai–said Parthasarathy, the lawyer.

In April 2018, the Maharashtra legislature passed an amendment to the LARR Act in the same way that Tamil Nadu did–by inserting Section 105A to exempt the Maharashtra Industrial Development (MID) Act and three other laws from its provisions. In effect, land acquisition for industries, highways, housing and for projects under regional and town plans would not be subject to LARR Act. It was approved by the President the same month.

But even before this, the state was using these older state laws to acquire land. In 2017, the Maharashtra government had issued notices under the Act to acquire land for the Rs 3 lakh crore ($44 billion) West Coast oil refinery in Ratnagiri. The project required 15,000 acres from 14 villages, affecting some 30,000 farmers and fisherfolk.

The proposal met with resistance from the local communities. A number of farmers led by land activist Ulka Mahajan met state officers at the government secretariat in Mumbai in October 2017 and asked why had they used the MID Act when the LARR Act was in force. “They had no answer,” Mahajan told IndiaSpend over the phone.

Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis had argued that acquiring land under the MID Act was necessary to give “fillip to industrialisation” in the state, and incorrectly claimed that it had provisions to seek consent.

“The MID Act does not have any provision for consent,” Mahajan said. “It is only when we do an andolan [agitation] that they stop forceful acquisition.”

Due to the objections raised by the farmers, the land acquisition process was cancelled in March 2019, ahead of the general elections in May.

Karnataka, like Maharashtra, continued to acquire land under state laws without passing any amendments to the LARR Act. Between 2014 and 2017, it had already used the KIAD Act to acquire over 4,300 acres of land, according to disclosures to the Comptroller and Auditor General of India.

In March 2019, the state government passed a bill amending the LARR Act, through which it exempted six state laws pertaining to land acquisition for industries, housing and highways. However, the state then issued a corrigendum removing the clauses that exempted the six laws.

R V Deshpande, who as the state’s minister for revenue had introduced the LARR Act amendment, said they issued the corrigendum simply because they did not want any “confusion” between state laws and the LARR Act. “LARR is a central enactment. We did not want any overlapping of that with the state laws,” Deshpande said. “The clause would have caused confusion and we wanted to avoid that. So we withdrew that clause.”

This has no effect on the Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Act, 1966, he said. “The point of amending the LARR was only to speed up acquisition of land for defence projects or other projects where land remains with the government,” he added.

Deshpande, who resigned after the Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) coalition government lost majority in the state legislature in July 2019, said he was not aware of the Madras High Court order.

Karnataka government officials said they still use the KIAD Act. “Yes, we are using the KIAD Act. There are four to five projects for which acquisition is underway,” said B Venkatesh, special deputy commissioner in charge of land acquisition for Karnataka Industrial Areas Development Board (KIADB), which has powers under the KIAD Act to declare any land as an industrial area and acquire it from landowners. Any government agency or private company that requires land for industries approaches the KIADB to carry out the acquisition. When asked why the KIADB is not using the LARR Act, Venkatesh said, “KIADB is an autonomous body.”

He did not name the projects for which land is being acquired.

One such project is well-known: the Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals Limited’s refinery, which wants 960 acres of land in its surrounding areas. Land is being acquired by the KIADB under the KIAD Act. It issued notifications to acquire the land in January 2017. The acquisition is still pending due to ongoing protests from landowners, who have demanded that the LARR Act be applied so that a social impact assessment can be done.

In case of disputes, the compensation would be determined by a special civil court as per the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, Dakshina Kannada district collector told the press in November 2018. This is because the KIAD Act says that all disputes are to be settled in terms of provisions of the 1894 Act.

B Venkatesh, the land acquisition in-charge of KIADB, confirmed this to IndiaSpend. “In case of any disputes, we are guided by the Land Acquisition Act, 1894,” he said. In contrast, under the LARR Act, disputes are to be settled by an independent LARR Authority.

The Karnataka court order

In Karnataka, a single judge of the high court had, in April 2017, ordered the state to stop acquiring land under the KIAD Act. But this was stayed by another bench of the court, after the state government petitioned it the same month.

The Madras High Court order would now be a shot in the arm for the petitioners in Karnataka, said an activist associated with the case, who did not wish to be named because the case is in progress.

The Madras High Court’s verdict, on July 3, 2019, said that it was improper for the state to “revive” the old laws by amending the LARR Act.

The state had argued that their amendment was valid because it was approved by the President. The court disagreed and said that the state laws had already become invalid in 2013 when the LARR Act was passed. This is because under Article 245 of the Constitution, when a new central law is passed on a subject under the Concurrent list (on which both states and the central government can make laws), all existing state laws that have provisions contrary to the central law automatically become void. (States can, however, make amendments to the central legislation.)

“Merely by inserting Section 105-A in the New Act,” the states could not revive three state enactments, the court said.

It went on to cancel all land acquisition carried out using the state laws since 2014, except in cases where the acquired land was already put to use.

The order has been hailed by land rights activists as a precedent for challenging the LARR Act amendments passed by Maharashtra and Karnataka.

Maharashtra has continued to use the MID Act despite the Madras High Court judgement. The state has now introduced an amendment to the MID Act that brings the compensation at par with the LARR Act, and expands the definition of affected persons, Smita Chaware, general manager (legal) of the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation, said. The amendment is awaiting the President’s assent.

But approving it may still be challenged in the court.

“In order to revive these acts, the State must re-enact these statutes, in accordance with Article 254(2) of the Constitution of India, and obtain the assent of the President,” the Madras High Court order read.

When asked about this, Chaware disagreed and said, “The whole Act does not have to be reenacted. That’s a misinterpretation of the court’s judgement.”

The Maharashtra laws would soon be challenged before the Bombay High Court using the Madras High Court order as a precedent, said Madhuresh Kumar, convenor of the National Alliance of People’s Movements, a coalition of land rights movements that has campaigned against the use of state laws.

“All three states have violated the central Act,” Kumar told IndiaSpend. “And the Centre had given its silent consent.”

(Nihar Gokhale is a writer with Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers and journalists documenting ongoing land conflicts across India.)

Courtesy: India Spend