The informal sector forms a pivotal part of the Indian economy. More than 90 per cent of workforce and about 50 per cent of the national product are accounted for by the informal economy. High levels of growth of the Indian economy during the past two decades has not changed this situation. Contrary to the earlier understanding that the informal sector would get formalised with economic growth or both sectors would operate in parallel, the new understanding is that there are strong interlinkages between the two. Most workers in the informal sector are deprived of secure work, workers’ benefits, social protection and representation.

The National Policy on Urban Street Vendors, 2009 (see box 1) has estimated that street vendors constitute 2 per cent of the population in various cities. Though street vending plays a vital role in providing livelihood to a large underprivileged section of the society, its contribution has not been accepted by city authorities or urban planning agencies so far. Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India provides all citizens the right to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business. At the same time, different sections of Indian Penal Code (IPC) and Police Act empower the executive to remove any obstruction on streets.

Also, Municipal Acts empower municipalities to remove encroachments on roads as obstructions. Lastly, vending on streets and open spaces is not considered a legal use in the city’s Master Plan or Local Area Plan as it does not conform to the land use provision in such plans. For city administrators, any land use in violation of the statutory plan demands eviction.

Together, multiple laws work towards evicting street vendors from urban space, thereby making them vulnerable to bribery and extortion by local government officials, police and mafia (who act as protectors) as a price to stay put. Realizing this, the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014, provides for reservation of 2 per cent of the city’s lands for vendors in a way that the ‘natural markets’ (markets that are naturally formed where there is demand), are protected. In addition, if any eviction is required, alternate space must be allocated to these vendors. In essence, the Act provides for allocating physical space to vendors in the city to protect their livelihood and provide city dwellers with easy access to goods and services offered by the vendors.

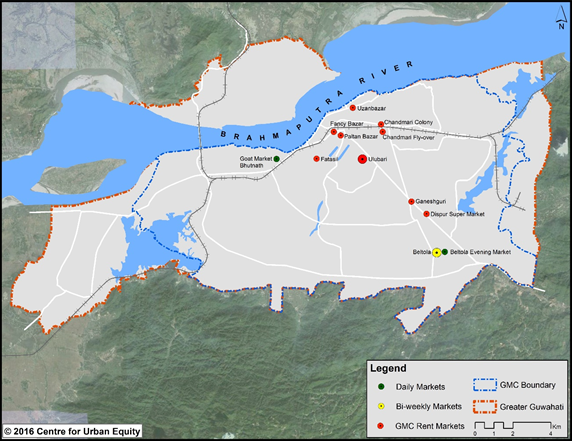

Guwahati has occupied a position of eminence as a trade and commerce centre for North-East India because of National Highway-37 and North-Frontier Railway based connectivity with the rest of the country. Additionally, River Brahmaputra is also used for transporting goods and people. This explains the existence of informal markets like Fancy Bazar, Machkowa and Uzan Bazar (Map on next page) along the mighty river.

“Poverty, Inequality and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning,” a three-year research project (2012-16) undertaken by Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University in Ahmedabad and Guwahati, and Institute for Human Development in Delhi and Patna, is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada and Department of International Development (DFID), UK, under the global programme Safe and Inclusive Cities (SAIC). The research analyses the pathways through which exclusionary urban planning and governance leads to different types of violence on the poor and by the poor in Indian cities.

The CUE research takes an expansive approach to violence, examining structural or indirect violence (material deprivation, inequality, exclusion), direct violence (direct infliction of physical or psychological harm), overt conflict and its links to violence and different types of crime, noting that not all types of violence are considered as crime (for example, violence by the state), and not all types of crimes are considered as violence (for example, theft).

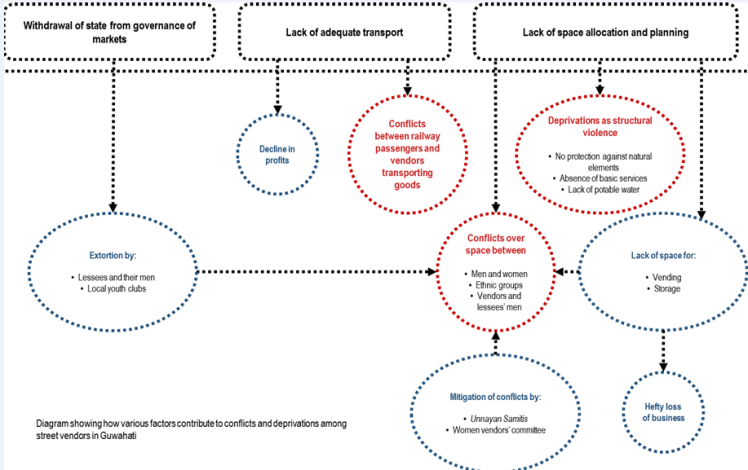

In Guwahati, the largest city in and gateway to the Northeast India, the research has focused on two hills, two street vendors’ markets and women’s safety in transport. Two markets, Ulubari and Beltola, have been studied. The partial withdrawal of the State from governance of these market spaces presents conditions for deprivations and conflicts among street vendors.

One of the oldest markets in the city is Kacharighat market where farmers (who came by boats and bullock carts), small traders and informal vendors sold grains, vegetables and poultry. Indigenous women (mainly from the Garo community) travelled all the way from neighbouring villages to sell hill produce and local vegetables in Kachari Basti market in Ulubari before leaving for home in the evening. As the city grew, especially after shifting of the state capital to Dispur, the demand for perishable farm produce continued to rise.

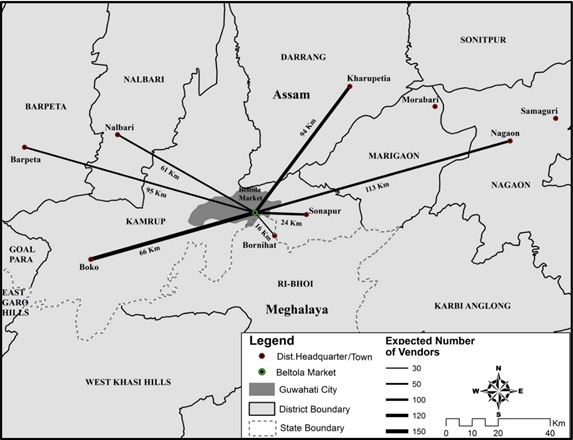

Improved transport connectivity made Guwahati an attractive market to people who now travelled (between 20 to 200 km) from settlements in Naogaon, Barpeta, Kharuptia and Rangia with their produce to markets in the city. Vending became an occupation not only for the poor in the city but also for farmers from the neighbouring countryside and districts.

TYPES OF MARKETS IN GUWAHATI

Guwahati has three major kinds of informal markets namely, a) GMC (Guwahati Municipal Corporation) rent markets, b) Daily markets, and c) Bi-weekly markets. In markets rented out by GMC, the shopkeepers pay a monthly rent to the local body directly. In the other two types of markets, GMC collects taxes through an annual lease under the provisions of the GMC (Lease of Parking Places and Markets) Bye-Laws, 2009. The lessee is identified on the basis of an annual bid where the successful bidder pays 30 per cent of the bid amount within 24 hours after the written offer is issued. The remaining 70 per cent has to be paid in nine equal instalments.

In order to maximize profit, the lessee employs people to recover as much money as they can from the vendors selling their wares in that particular market. Owing to the lack of any fixed rents or regulation, conditions favourable for exploitation are created, which then has potential to create conflicts between the lessees and the vendors.

Additionally, there are markets on roadsides, community lands or public land that are managed by Unnayan Samitis (Lakhra), youth clubs (Garchuk) and influential individuals (along the highway in Garchuk). The Unnayan Samitis pay taxes to GMC and recover charges (as high as INR 20 to INR 50 daily) from the vendors. The rates are linked to the wares that are being sold. Usually, cloth and meat vendors are charged INR 50; Sunday market vendors are charged INR 100 and for permanent kiosks, the rates exclude electricity charges.

Unnayan Samitis provide lighting, undertake cleaning and development works using the charges collected from the vendors. Youth clubs collect charges but some of them (for example in Garchuk), reportedly do not pay anything to GMC. The Indian Railways has also given land on lease to vendors in Bamunimaidan where it collects INR 5 per day from each vendor. Other markets along the roadside in Guwahati report payment of INR 20 per day to the GMC appointed tax collectors as scavenging tax. Sometimes, tax collectors would demand INR 10 (instead of INR 20) without offering any receipt to the vendors.

This then means that the vendors have to bear the costs of loss of business. A participant said:

“Two years ago, my son was beaten by one passenger when we were trying to get into the train with our vegetable bags against their advice. We tolerated this brutal act [of the passenger] and didn’t say anything.

“This is our livelihood and hence we have to go by train. We do not have any other work to do. We are doing this work due to extreme poverty and have only this option for our survival.”

Passengers often complained to Railway Protection Force (RPF) and Government Railway Police (GRP) personnel about the vendors. The RPF/GPF personnel in turn, harass the vendors, collecting bribes of INR 20-30 from each vendor per trip. Sometimes, they get into physical conflicts with the vendors. Owing to the lack of proper transport options, vendors bear additional economic, emotional and physical losses while transporting their wares from their settlement to the market.

When vendors are unable to sell their entire stock in a day or missed the last train back home, they are forced to stay back in the city at night. Owing to the absence of night shelters and storage spaces, they spend the night at the railway station. Participants reported that they ended up losing their money and goods to thieves while asleep on the railway platform. Thus, not only did they feel unsafe in the city at night but there were also economic costs of unwillingly spending the night in the city. Women vendors also feared sexual harassment in addition to other problems reported by male vendors while sleeping on the railway platform.

“One day, a RPF cop demanded INR 100 from me. When I couldn’t give money, the cop kept one bag of vegetables with him and asked me to load the remaining bags inside the train. I was furious and shouted at him. He did not return my bag. I lost my patience and caught his shoulder; his badge came into my hand. He was scared and returned my bag of vegetables.”

Space crises

Conflicts due to lack of space: Earlier vendors cooperated with each other to adjust space for displaying each other’s wares, however congestion in the markets has led to vending space-based conflicts. For example, most women vendors in the Beltola market occupy a space whose area fell between 6 to 12 square feet per stall, while most men vendors occupy more than 35 square feet space per stall. This causes great tension between female and male vendors with the former feeling unhappy about the capture of the limited vending space by the latter. This often results in verbal fights. When matters go out of hand, women reportedly throw away their male counterparts’ vegetables to stake and reinforce their claim on the vending space.

“In case, someone occupies my space, I scold and fight with him to take my place. And if that doesn’t work, I throw away his vegetables.”

Conflicts aggravated in this market because the GMC converted one of its municipal grounds used for vending into a multi-storey building which led to a loss of vending space for male vendors. These vendors were not formally relocated, and squeezed themselves into nearby markets where women vendors operate. This imposed high economic costs on the vendors who had to pay tax not only to the lessee but also to the earlier occupant of the vending space (as high as INR 100-200 per day). Some were forced to sell their livestock back home to deal with loss of business owing to space crunch. There are other conflicts between vendors on space, which are played out on lines of gender, ethnicity and length of association with the market.

Conflicts are also reported between tribal vendors and migrant Muslim vendors. The tribals raise issues of ethnicity to stake their claim on vending space. Similarly, Garo vendors come seasonally to the Ulubari market but enjoy higher claims on the vending space and invariably get into verbal conflicts with regular vendors.

“We have been vending here since inception of this market; you people should leave space for us on market days.”

The local Unnayan Samiti opined against the claims of the Garo vendors arguing that since the latter were not regular in coming to the market they cannot stake claim to the space in the market. The regular vendors did not usually protest, but instances have been reported where conflicts quickly escalate into physical fights with vendors throwing vegetables away from the vending space. Overall, the management of vending space by lessees and vendors committees is found to be informal and ad-hoc, with no responsibility being taken by these actors to resolve conflicts between vendors. Vendors are forced to spill over and occupy spaces on nearby footpaths. They also pay heavy economic costs in terms of loss of vegetables and loss of opportunities for selling their wares.

Lack of storage space: Vendors face problems in storing their unsold goods, weighing instruments and plastic sheets that provide them protection from the elements. Around 72 per cent and 47 per cent vendors in Beltola market and Ulubari market respectively were unable to store their wares. They often sell their remaining goods, mainly vegetables, at throwaway prices by the end of the day, thereby incurring losses. Many vendors rent rooms near the market for living as well as for storing their wares. Around 17 per cent Ulubari market women vendors use storage spaces rented by the local women vendors’ committee while 27 per cent vendors stored their wares behind their vending spaces. The lack of storage spaces impose economic costs on the vendors.

Mitigating conflicts over space: However, there were also mechanisms to mitigate possibilities of conflict over space. In Beltola market, few residents and shopkeepers rented out their front yard to vendors who paid the former rent on a monthly/ weekly basis. These residents/ shopkeepers become custodians of the space rented out to vendors in the latter’s absence for short periods of time. Similarly, when a vendor who sold her/his wares on the main road is unable to come for many days, neighbours take care of that space. They allow new vendors to occupy the above mentioned space temporarily, but not after the arrival of their absent neighbour. Informal relations, acquaintance and camaraderie governed the local management of vending space in this case.

In Ulubari, the earliest vendors had merely occupied different portions of the available space. Later, as the number of vendors rose and a women vendors’ committee (Unnayan Samiti) was formed, spaces were earmarked by the committee for women vendors (especially tribals) coming from different areas. It was reported that women vendors coming from Bornihat and Sonapur enjoyed the first right over vending space followed by those coming from Barpeta Road. Muslim male vendors were the last ones in the pecking order. Thus, the space management in Ulubari is slightly more formalized than Beltola.

Vendors braving the rains in Guwahati

Deprivations as structural violence

No protection against natural elements: Our FGDs revealed that lack of protection from the elements was a major concern for street vendors. Since they were poor, they had no option but to continue selling their wares under the sun. This led to health problems like headaches that ate further into their already meagre earnings. Owing to the lack of protection from the elements, street vendors lost business on days when conditions were not favourable, especially during monsoons and summer.

“Last Sunday, I had a severe headache and pain in my waist. Hence, I gave all my vegetables to another vendor and went back to home.”

Box 1: Highlights of the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014

i) The Act aims to protect the livelihood rights of street vendors as well as regulate street vending through demarcation of vending zones, conditions for and restrictions on street vending.

ii) A Town Vending Committee (TVC) to be formed for every town. Any person intending to undertake street vending needs to register with the TVC. He/ she may then apply for a vending certificate that will be issued based on various criteria.

iii) The TVC comprises of the municipal commissioner, representatives of street vendors, local authority, planning authority, local police, resident welfare association and other traders associations.

iv) The state government to frame a scheme for street vendors. The local authority, in consultation with the planning authority, to frame a street vending plan once every five years.

v) Natural markets (those that have come up naturally on account of demand) not to be disturbed while framing street vending plans.

vi) No eviction of vendors to be undertaken without relocation.

vii) The Act recommends the reservation of 2 per cent land for vending as part of master plans and local area plans

Deprivation due to absence of basic services: The absence of public toilets, potable water and storage spaces are considered as major concerns of vendors. The lack of these facilities affect women vendors more than their male counterparts who chose to relieve themselves nearby. Women vendors from Sonapur reported that since no toilets are available at the markets, they go to neighbouring houses for relieving themselves. Sometimes, the nearby house owners make uncharitable remarks on them. Also, going to neighbouring areas takes time and they have to leave their wares unattended or in the care of neighbours, often resulting in thefts.

“If I consume more water, I need to go to urinate frequently, thus I take less water as far as possible.”

Women therefore avoid drinking required amounts of water to reduce frequency of urination, resulting in health problems such as urinary tract infections in the long term.

In Beltola market, a large proportion of the participants reported using road-side space (28 per cent) and nearby houses (28 per cent) for relieving themselves at the cost of hygiene and dignity. Similar concerns were echoed in Ulubari where the local women vendors’ committee had rented a toilet but access was controlled through a lock whose keys were not accessible to all. As many as 47 per cent of the women vendors used this toilet whenever it was open. Otherwise, they depended on their friends’ homes in the neighbourhood. A three-seater toilet rented by sSTEP, an NGO, was considered inadequate considering the volume of vendors that sell their wares at the market.

“In case, we feel an acute need to visit the toilet, we go to the drain. At that time, we do not think about our self-prestige and dignity. I mean, if men would see us relieving ourselves…”

Deprivation due to lack of potable water: Another major concern stated by vendors was the unavailability of potable water. One-third of vendors in Beltola market purchased expensive packaged water for drinking purposes. Others brought water from their homes or got water from nearby hotels and temples for sprinkling on their vegetables to keep them fresh. In Ulubari market, close to half the vendors brought water from home for drinking and other purposes.

Ad-hoc nature of tax collection by lessee resulting in conflicts

Although the tax rates to be collected by the lessee are fixed, many overcharge. In Beltola market, lessee charged the vendors more tax than that prescribed by GMC for its markets – more so during the interim period when lessee’s contract period lapses and fresh tenders are invited by GMC. Clause 22 of terms and conditions for settlement of the markets of GMC (2013) states that “the lessee shall collect toll at the prescribed rates only.” In case of complaints against demanding excess tax, either by the lessee or by their agents or employees, “the lessee shall be liable to be prosecuted U/S 384 of IPC and lease shall be terminated forthwith.”

Clause 35 of the terms and conditions states that “the lessee shall display a signboard of the approved rates of toll at a prominent place in the markets at their own cost.” Our survey revealed that while GMC does not allow collection of more than INR 70 per vendor per day, the lessee collected up to INR 300 per vendor per day. Vendors reported that the lessee’s tax is not only high but it also varied temporally and from one vendor to another.

For the first few months of a lessee’s tenure, the vendors paid INR 100 which gradually increased to INR 300 by the end of the year. The lessee also collected INR 200 from each truck at night as parking fee in violation of the terms prescribed by GMC. The vendors strongly resented the lease system due to high economic costs, however the vendors did not challenge the lessee as he evokes fear of bodily harm and fear of loss of vending space in the market.

Extortion by local youth clubs and goons

The vendors get harassed by local goons for money when they went to the market at night with their goods. The vendors were not able to defend themselves against the goons as they feared for their safety. They perceived the policemen to be in nexus with the goons.

“Once, we reached Beltola market at 2 am and were unloading our goods from the truck. Some drunken local goons asked for INR 1,000. When we refused to pay, they beat us. Only police can help us in this kind of situation. In Beltola market, lessee and local goons beat us, no one comes forward to rescue us.”

Besides local goons, different groups of local boys also harassed them by asking huge amounts from INR 500 to INR 1,000 for celebrating Bihu, Durga Puja and other local festivals.

“For any festival, chanda can be given once but in Beltola market, every market day local boys collect chanda. On the first market day, local youths take INR 600, then on second market day INR 200 and then INR 300 on third market day and so on.”

These kinds of extortion have a huge impact on the already meagre incomes of the vendors.

VENDORS’ RECOMMENDATIONS:

# Beltola market vendors suggested that GMC should not award tax collection through competitive bidding as it increased the bidding price by as much as three times when compared to the base price. The lessee then has to recover this money from vendors, ultimately increasing the tax burden on vendors.

# There was a need for greater vigilance by police. Since GMC collects huge taxes from the markets, police force must be deputed to maintain law and order in the markets, especially at night.

# To avoid conflicts between regular and irregular vendors in Ulubari market, participants suggested that vending space should be allotted to regular male and irregular tribal women vendors separately.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The state’s withdrawal from governance of the markets has left the space open for exploitative private parties to conduct their business. GMC should ensure that its withdrawal from the markets must be accompanied by the creation of representative market management committees that can safeguard the interests of the vendors. At the same time, the GMC should also plan for vending spaces in the city.

# The development plan mechanism must identify and reserve spaces for local markets as recommended by the Street Vendors’ Act of 2014.

# GMC has completed street vendor surveys in Guwahati. The formation of street vending committees and zonal vending committees in all markets must be expedited.

# GMC must delineate a) free vending areas – where street vending is allowed without restrictions, b) restricted vending areas – areas where vending is permitted on specific days or time or by trade, and c) no-vending zones – streets having arterial/ heavy traffic. Vendors affected by the creation of no-vending zones must be accommodated in vending zones nearby through the use of measures like time-sharing that can be implemented using the TVC/ZVC mechanism.

# The process of issuing licenses to street vendors must be expedited. These licenses must include names of beneficiaries, name of the market, timings and charges to prevent harassment by various state and non-state actors.

# Street vending schemes must by virtue of their design exhibit sensitivity to the needs of the vendors and their customers, especially women, children and differently-abled.

# GMC must contribute towards building the capacities of vendors so that they can come together and form market management committees for their governance.

# GMC must help prevent exploitation of vendors by lessees, private plot owners and vendor committees. In lieu of a nominal tax collected from the managing body, the vendors and their customers must be given access to clean and safe markets.

# The state must ensure the safety and security of women vendors who feel threatened by their male counterparts and unwelcome owing to the lack of basic facilities like sanitation, storage and night shelters. Access to basic services such as shade, potable water, well-lit and clean toilets must be ensured. In addition, facilities like night shelters and storage spaces for vegetables and other belongings of vendors need to be provided.

—

*This is the fourth Policy Brief in the series prepared by the Research Team (Guwahati) of the Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University, Ahmedabad, on “Safe and Inclusive Cities – Poverty, Inequity and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning” . One of the researchers is from the Society for Social Transformation & Environment Protection (sSTEP)

Courtesy: CUE, CEPT University, Ahmedabad

Courtesy: counterview.org