Mumbai: The most visible sign of discrimination on campus was the “curtains” requirement: The windows of rooms occupied by women had to have curtains; there was no such requirement for men at the Regional Institute of Education (RIE).

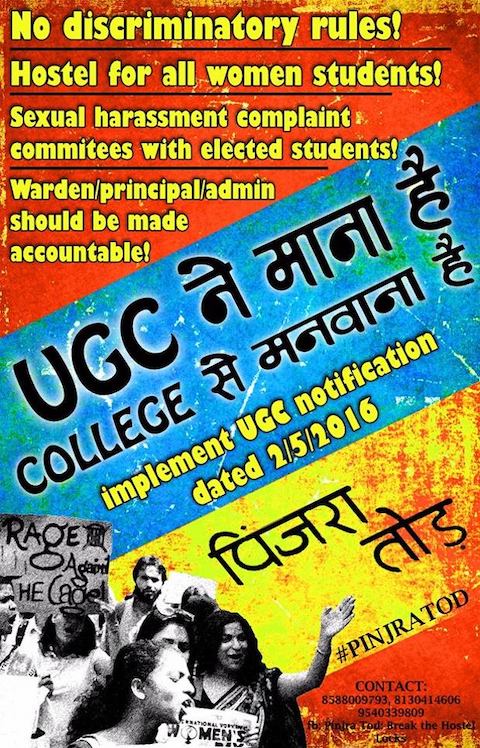

A Pinjra Tod march on International Working Women’s day, March 8, 2016, where students from colleges across Delhi gathered to demand the removal of hostel curfews, regularization of private accommodation, and the setting up of sexual harassment redressal mechanisms.

RIE offers a four-year undergraduate degree across five campuses, in Ajmer, Bhopal, Bhubaneswar, Mysore and Shillong. Until a few months ago, the lives of the female students were dictated by the position of the sun in the sky. Before sunset, they had to be locked indoors.

“Grille time could be 5:30 or 5:45 pm in winter, and 6:30 pm in summer,” one of the young women at the Bhopal campus–requesting anonymity–said, referring to the metal grille door that would be locked at curfew hour. Classes ran from 9:15 am to 5:30 pm, so they went straight from the classroom to the hostel. They could neither play outdoor sports nor order in food, if they didn’t want the usual mess fare.

If a student got sick, she had to get the chief warden (a warden designated chief of all wardens of all campus hostels) as well as the head of her department to sign her pass before she could leave campus. The library was open until 8 pm but women students had to write out a special request if they wanted to use it. A guard would have to escort them to the library and once there, they had to stay put until closing time, when guards would escort them back.

Male students had no escorts.

Some of the young women were chafing at the unfairness. They wanted to protest but did not know how to start. For advice, they turned to Pinjra Tod (break the cage), a collective of women students that started in Delhi but has since connected with colleges nationwide.

When students at RIE Bhopal contacted Pinjra Tod, they were advised to first build consensus. It was hard work because some students felt the discrimination was justified, for their own safety.

“The seniors wanted deliberations, which meant, talk to professors,” said an RIE Bhopal student, requesting anonymity. “So we asked for grille time to be extended by 15 minutes–6:45 to 7:00 pm. It didn’t happen.”

They kept talking to each other about demanding change rather than “deliberating” it. Then, a new batch of B Ed and M Ed students entered campus. They were older, more confident and a little better equipped to raise demands. When the protest finally started, most resident students ended up supporting it.

Male students too were willing to protest, but some of the girls worried that their presence could dilute the force of the women’s demands, so they were asked to stay away. The men helped by putting up posters instead, and bringing food for the protesters.

At grille time, the girls stepped out of the hostel and sat down in the playground. The security in-charge came a few times, asking them to come back in. Then, the wardens of both hostels came, then the chief warden came.

“We did not move,” said the RIE student. “Then, they said, ‘the principal is sick’. So, we settled for a letter from the wardens assuring us that most of our demands would be met within 24 hours.” The next day, the authorities went back on their word. Again, the women went outside at grille time and this time, they stayed out all night.

Students at the Regional Institute of Education, Bhopal protest against restrictive hostel curfews on September 15, 2018. The college authorities conceded and extended curfew hour. However, there have been fresh protests in April 2019.

Word got out and soon, the students were fielding media interest. Some journalists showed up, but the administration blocked them from meeting the protesters. Social media, however, could not be controlled. When Yogendra Yadav, national president of the Swaraj India party, tweeted about the protest, it was instantly amplified.

As the protest gained momentum, the protestors used scarves to mask their faces, to make sure nobody was singled out for punitive action. The RIE Bhopal student who spoke to IndiaSpend also asked to remain anonymous. “The authorities told us to remove our masks,” she said. “We refused. They wanted to meet our ‘representatives’ separately. We said, no, discussions had to be open. This went on for a while. Finally, they agreed.”

Ultimately, it took just three days to change discriminatory rules that had been in force for decades. Ever since the curfew was extended, their lives have changed significantly for the better. The girls can watch plays, attend seminars. Some have joined gyms or coaching classes for competitive exams, others dance.

We sought comments from former principal of RIE Bhopal, Hrushikesh Senapaty, currently a director at the National Council of Educational Research and Training, but he did not respond to phone calls made or emails sent over eight days.

An unquiet revolution, as women leave home

Protests like the ones at RIE are not isolated events. An unquiet revolution has been brewing in hostels across India. From Jammu to Thiruvananthapuram, young women are breaking open locks on gates, marching on the streets and sleeping under the stars.

In 2017, Mumbai University did away with an 11 pm campus curfew for women students, as did the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Roorkee, and the year before, the Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS) campuses in Pilani and Goa. In 2018, Delhi Technological University shifted its curfew from 9 pm to 11 pm.

Punjabi University, Patiala, had young women sitting in at night, while others went on hunger strike to demand 24-hour entry to their hostels. During one protest in Miranda House, the young women decided to put a lock outside the gates, locking in the authorities for a change. It was also the year when, for the first time in its history, the hostel gates at Lady Shri Ram College in Delhi were forced to stay open all night. The year ended on a high note, with Panjab University, Chandigarh, agreeing to unrestricted hostel access.

This year, 2019, has brought more victories. After two years of protests, curfew hour at College of Engineering, Trivandrum was extended from 6:30 pm to 9:30 pm. The Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur, extended from the women’s curfew from 4.30 pm to 8.30 pm.

Not all these protests identify with the Pinjra Tod collective. Some are inspired by it and even seek help, but choose new names for their campaign. In 2017, women in Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak, broke locks when a winter curfew prevented them from watching a play being staged on campus. After they succeeded in getting the 6 pm curfew extended to 8:30 pm, the group called themselves azaad panchhi (free birds), for the cage was broken.

Pinjra Tod sees itself as “a network of solidarities” rather than an organisation. Some of its activists agreed to meet this writer in Delhi but insisted on talking as ‘we’ rather than ‘I’.

“The media always asks for leaders or ‘founders’. This is neo-liberal discourse,” they said, adding that they are wary of the quest for a charming anecdote, or stories about the heroism of individuals. They are also troubled by media focusing on night-time marches. “It’s a way of framing us: girls out at night. For us, the question of equal access to education is the bigger one. Education doesn’t happen only in classrooms.”

The conflicts have grown because women are getting an education and leaving home in record numbers.

There are 799 universities, 39,071 colleges and 11,923 stand-alone institutions in India. Of these, 14 universities are exclusively for women, according to 2016 government data, the latest available. Higher education tends to be concentrated in urban areas. Bangalore district alone has 970 colleges, while Jaipur has 616. Just 50 districts account for 34% of India’s colleges.

It is inevitable that students leave their homes and live in hostels, if they are to pursue higher education.

Despite this, over 16 million young women now go to college and while their numbers are lesser than their male counterparts’, they are catching up. Women account for more than 46% of total enrolment in higher education in India, up from 39% about a decade ago, according to the All India Survey of Higher Education, 2015-16.

Across central universities, there are 3,081 hostels for young men, housing more than 750,000 students, and 2,265 hostels for 490,000 women. At the state level, the figures are more apposite, with 20,565 college hostels for 1.8 million women students and only 18,179 hostels for 1.9 million men, according to the survey data.

Clashes with authorities are inevitable and, for every victory, there is new resistance.

Resistance, amid victories

The RIE administration did not extend the freedoms its young women wrested from it to other campuses.

But word spread through social media and soon, protests began at RIE Ajmer.

A third-year student at the Ajmer campus told this writer that the administration initially made the “usual” excuses. “They said, the principal is not available, so no changes can be made. But after we’d stayed outdoors for a whole day, they accepted most of our demands.” The hostel curfew was extended to 9 pm.

The protesting students chose to stay anonymous because they worry about being expelled on flimsy pretexts. It is why many protesters cover their faces, using their “collective anonymity” as a shield against punitive action. The Central University of Rajasthan also saw protests with students covering their faces while demanding the removal of biometric attendance and surveillance systems, the abolition of curfew, and starting democratic elections. Several students had already been expelled for joining protests.

One example of extreme punitive action is Shivangi Choubey, a former student at Banaras Hindu University (BHU). She had participated in the 2017 protests, which started after the authorities refused to take cognisance of sexual harassment on campus.

Gender discrimination was also endemic: Unlike men, women were not served meat in the hostel mess, nor allowed to use mobile phones after 10 pm, and there was no WiFi in the women’s hostels.

Choubey, then an undergraduate, said a Zee News crew showed up to cover the protests. “The chief proctor told the crew that the protest was politically motivated, that we were not BHU students but had come in from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU),” she said “So, we went to her office and demanded that she either apologise or prove her allegations. Next thing we heard, she filed a police complaint alleging that she had been attacked.”

Had the police accepted the proctor’s “attempt to murder” version of events, Choubey could have gone to jail. They quashed the charge. Still, 11 students, including Choubey, were debarred from the university.

It started with a Facebook page

The Pinjra Tod story began in 2015, with Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI) University in Delhi. Earlier that year, a group of students had started a campaign called “Pads Against Sexism”, which involved putting up sanitary pads in public spaces with messages written on them to remove the stigma against menstruation.

The administration responded by issuing show-cause notices to the students. A few months later, the administration disallowed “late night” outings for students living in hostels. They could stay out until 10 pm twice a month before, and even this was permitted only with the written consent of a “local guardian”.

The imposition of night restrictions at Jamia was an unpopular move, and some women pushed back. Initially, they sent a petition to the Delhi Commission for Women (DCW), complaining of discriminatory practices. The commission took suo moto notice and sent a notice to the vice chancellor and administration of JMI.

IndiaSpend sought a response from the vice chancellor about the university’s response and about their current position on hostel curfews, but emails have gone unanswered.

The students did not want to limit their complaint to just one university. Other colleges imposed similar restrictions and, it emerged that curfew hours were worse elsewhere. So, they began to compile a report that could be used to petition on behalf of students across institutions.

A Facebook page, “Pinjra Tod: Break the Hostel Locks”, was created. Some of the student activists had earlier conceived of a newsletter about women’s lives at Delhi University. For now, they decided, a Facebook page would do.

A couple of early posts trickled in, then suddenly there was a flood.

Locked in during an earthquake

One of the stories that went into their 2016 report came from a young woman who was president of a cultural society that hosted after-dinner talks at St Stephen’s College, New Delhi. At 9:40 pm, she would have to apologise to the invited speaker and run towards her hostel.

“It was humiliating,” she wrote but not turning up for the roll call at 10 pm meant immediate expulsion. “I was once late by 10 minutes. The warden locked the door and made me stand out pleading.”

A B Tech student at JMI reported setbacks like not being able to participate in a workshop at IIT Delhi because it would go on until 8 pm; her hostel’s authorities were not willing to extend her curfew even for the duration of the workshop.

One student from Delhi’s Indraprastha College for Women lived at a privately owned hostel and shared this story: During an earthquake in 2011, the girls living on the topmost floors were locked indoors; their warden had left for the day. After this scare, nothing changed. The next year, a short circuit led to a fire and again, the girls on the top two floors had no way of getting out of the building. Another story was about a girl who broke her leg, and the owner of the hostel refused to rush her to hospital.

Other girls complained that they were not allowed to step out at night, even when they had an early morning train or a flight to catch. As a result, they were forced to spend the night at airports and railway stations.

Every story in the Pinjra Tod report confirmed discrimination: Citizens old enough not only to vote but also to marry and have children–some of them even old enough to contest parliamentary elections–were locked in, unable to participate in the cultural and academic life of the university. These were adult women who could not take a walk around the lawns or eat a meal off campus without written permission from local guardians.

Guardians and inequality

All Indian colleges and universities insist on a “guardian” rather than a local emergency point of contact for undergraduate, graduate and even doctoral scholars. This guardian decides whether or not a student can watch a movie or attend a workshop.

The sexism extends to guardians too.

A college teacher wrote in to say that when a friend’s daughter needed a local guardian, she volunteered. However, Daulatram College hostel refused on the grounds that she was single; in addition, she was treated to a lecture on the “morals of womanhood”.

When IndiaSpend contacted Daulatram principal Savita Roy, she declined comment, saying the hostel was not under her control and that the college chairperson was responsible for its administration. The college website said that the hostel was “directly under the control of the Principal who is assisted by the Warden…” A news report from February 2019 suggested this ‘control’ is difficult to enforce and that wardens do not, in fact, take their cues from the formal authority figure.

A Pinjra Tod activist, Natasha Narwal, said class discrimination is also built into the “local guardian” requirement, since colleges assume that a student already has connections in the city. This is not true for many families. Even if a local contact is found, this individual is rarely invested in the student’s welfare or the fulfilment of her ambitions.

Natasha Narwal, who first came to Delhi in 2006, pointed out that even co-educational colleges do not offer equal housing. She enrolled at Hindu College as an undergraduate but was forced to live as a paying guest because there was no hostel for girls.

“Yet, the college had money from the UGC [University Grants Commission], which sanctions a girls’ hostel,” said Natasha. “We found out when we filed an RTI [right-to-information request]. The excuse given by the administration was that it is a heritage building and permissions are needed from the Archaeological Survey of India to build anything new.”

Finding housing as a student did not get easier while she studied towards a Masters and then an M. Phil degree. “There was an average of just two hostel seats per course offered at the university. I always had to stay at private hostels. They too had curfews, some as early as 7:30 pm. Many girls made duplicate keys on the sly or jumped over the gates when they had to.”

Devika (she requested we use one name), who was also living as a paying guest (PG) at a private hostel in Delhi when she first heard about the campaign, said private hostels were unregulated. They are more expensive, and the facilities are worse. Singh paid Rs 11,000 per semester, which jumped to Rs 14,000 by the third year. “Landlords insist on cash transactions,” she said. “They pay no taxes, issue no receipts, so we have less bargaining power.”

Difficulties in changing the discourse

Pinjra Tod is keen on changing the discourse around student rights. Apart from affordable university housing and 24×7 library access, women students want all-night dhabas (eateries), regularisation of private hostels and elected committees to deal with sexual-harassment complaints.

However, curfews remain the major focus of protest.

Young women argued that Delhi is more unsafe than it would otherwise be because women are demobilised. The 2012 gang-rape and murder of Jyoti Pandey, better known as “the Nirbhaya case”, has only made matters worse.

They accuse hostel authorities of “weaponising” the incident to control young women. Delhi’s Indraprastha College, for instance, had a regular curfew of 7:30 pm, but hostel residents were allowed four late nights a month when they could return at 10:30 pm. After 2012, the late night curfew was pulled back to 9:30 pm.

Delhi University has close to 80 affiliated colleges and more than 700,000 students. However, it has ignored protests about curfews. The students also accuse the university of fobbing off demands by citing the semi-autonomous status of certain colleges.

The Khalsa College hostel, for instance, is run by a gurdwara (Sikh temple) management. The university and the gurdwara pass the decision back and forth, even though the UGC has said women’s mobility cannot be curtailed in the name of security.

Hostel administrations tend to view all protest as a mark of indiscipline.

Faced with a serious water crisis at the Rajiv Gandhi Hostel for Girls–hundreds of students had no water to bathe or wash with–the administration wrote to the parents of some protesters, accusing the girls of “bringing disrepute to the hostel”.

In 2017, Pinjra Tod was even accused of terrorism. Ritika Thakur, who was at Hindu College at the time, had participated in a protest about the lack of a girls’ hostel. Soon after, she said, the administration tried to intimidate students through show-cause notices and a disciplinary committee hearing. “We refused to attend the hearing,” said Thakur. “Then someone from the college office called my father and said your daughter is involved with terrorist activity.”

Students jump over the gates of Hindu College, during the Pinjra Tod night march in September 2016. The college did not have a women’s hostel until 2016 and when it did finally build one, it was smaller and nearly five times as expensive as the men’s hostel.

Her parents lived in Himachal Pradesh and did not know what to think.

“My parents were crying and yelling over the phone. They thought I’d been brainwashed into doing something wrong.” She was not cowed, though. She stayed put in Delhi and did not talk to her family for weeks.

After she finished her degree, Thakur returned to Himachal Pradesh and, to her surprise, found the hostel culture there less restrictive. “We have curfews, but it isn’t as bad as in Delhi,” she said. “We don’t have to explain to wardens why we want to step out. We expected Delhi University to be more progressive but it isn’t.”

Eventually, Hindu College did build a girls hostel but the fee was Rs 1.5 lakh per year, five times the fee for the men’s hostel.

The gender tax

Pinjra Tod found what they call a “gender tax”. The average monthly fees paid by undergraduates for college hostels was Rs 8,083 for women, and Rs 5,125 for men, said Pinjra Tod’s 2016 report. The respective monthly average for postgraduate hostels was Rs 7,140 for women and Rs 4,526 for men. Many women’s hostels charge additional fees for “security”.

Another Delhi activist, Avantika Tewari, said she and her fellow students were “taken aback” at the way “progressive” women’s colleges, such as LSR and Miranda House, have reacted.

LSR, for instance, asked the girls to pay higher fees if they wanted to abolish curfew, to hire more guards, install new doors and a biometric attendance system.

Tewari traced the argument to the upper-class Indian view of education. “When we ask for changes, they respond with fee hikes,” she said. “We must work overtime to pay the fees. But to work overtime, we need to be out later, which is not permitted. The idea is that parents must finance the education of children well into their twenties. So then, who can access higher education?”

The message spreads

To discuss questions of women’s access to space and facilities at their universities, Pinjra Tod held a jan sunvai (public hearing) in October 2015. Students called professors and lawyers, and started a signature campaign. Delhi University walls were covered with graffiti and posters.

They decided on a night march, walking dimly lit streets and cutting through college campuses to bring attention to the fact that women students were locked indoors. At Miranda House, they noted, women were not allowed to go up to the terrace even though it is a women’s college, nor could they use the basketball court at night.

A Pinjra Tod poster pointing out that the University Grants Commission acknowledges women’s right to mobility and that Delhi University must also adopt a similar position on the question of hostel curfews.

When Devika heard about Pinjra Tod, she got herself added to their WhatsApp group. Girls could not attend meetings easily because of curfews, so WhatsApp was the venue for important conversations. It was also how they shared strategies and offered advice. They did not know how many students they were reaching, but every time a call for a protest went out, at least 100 young women showed up.

One of Pinjra Tod’s early campaigns was about access to DU’s central library. Women students could stay only as long as their curfew permitted, although the reading room was open until 11:00 pm. Pinjra Tod called for an event–“Library of our Dreams”–outside the central library. Students brought their own bookshelves and sat outdoors after curfew hours. Exams were around the corner, so some of their professors and seniors also showed up to help.

Along the way, they learnt to innovate. At another protest, some students impulsively climbed a gate, shouting “Pinjra Tod!”. Next time, the group brought a ladder to climb over walls. Another time, the group found itself locked out of a venue where they wanted to demonstrate. So they staged a “die-in” instead: lying on the road and playing dead.

A flashpoint came when Pinjra Tod protested at the “wall of democracy”, a wall near the Delhi University Arts faculty building that students frequently cover with posters. Students affiliated with the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the youth wing of India’s ruling right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party, tore their posters.

“We put our posters on top of their old posters since their event was already over,” said Devika. “Then one of their activists called to threaten us. We decided to filed an FIR [first information report]. Word went out on WhatsApp and 50-60 women showed up at the Maurice Nagar police station.”

That show of solidarity gave the activists strength to press on and go to court. Eventually, the man who made the threatening call apologised in writing. They refuse to name him.

The power of solidarity

Solidarity also offered lessons in negotiating power at home.

Tewari, for instance, did not have hostel problems when she joined Pinjra Tod. She lived at home with her parents. However, she had internalised the usual arguments against going out at night, for education, fun or politics.

“When I first started going to protests, I’d tell my parents that I was going to a friends’ house,” she said. “Once I said, I’m going to a Diwali party. I left the house all dressed up, holding a box of mithai (sweets), but I went to a night march. I was negotiating–what’s acceptable as a good excuse to be out?”

“Before the movement,” said Tewari, “There were few individuals you could rely on. If something goes wrong at home, you can call a friend and say, take me in. But for how long?” Pinjra Tod introduced her to ideas like women keeping an open house for each other. “We learnt that we can take care of each other collectively. You don’t have to be a burden on any individual or family.”

As photos of protests, posters and statements went up on Facebook, women from other campuses began to send messages, sharing information about campus protests across India.

There were attempts to defy curfew at the Ram Manohar Lohia National Law Institute, Lucknow, and at the Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur. At Aligarh Muslim University, during a major protest on campus, the administration locked women up inside their hostels as early as 3:00 pm to ensure their “safety”. Some of the women broke the lock, made a video, uploaded it and tagged Pinjra Tod to let them know.

Some protests go on for months, even years, like the ongoing struggle at Sri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu. In 2017, women had objected to the installation of another security gate, which they said would affect them psychologically, making them feel further incarcerated. The vice chancellor was quoted as saying: “Psychologically affect ho rahe ho to paagalkhaana jao” (If you are psychologically affected, go to a mental asylum). Since February 2018, the administration allegedly began to blacklist students, threatening them with suspension for writing “Pinjra Tod” in the register that they had to sign while entering and leaving the hostel.

Meanwhile, the Pinjra Tod collective realised that existing freedoms could also be lost.

Devika has since moved to JNU, where women were not locked up at night. When she first moved here, she repeatedly asked the guards: “Can we really go out at night?” She recalled walking for kilometres, just because she could.

However, in September 2018, the administration allegedly tried to confine the residents of one of the women’s hostels after some violence erupted on campus. “It was a typically patriarchal response. Locking up the women instead of the men who needed locking up,” Devika said. It had not been typical of JNU though, not until then.

The students pushed back, refusing to be confined. One of the dhabas on campus had been shut down, which made the girls feel much less secure at night. In response, a group including Devika set up a ‘guerrilla dhaba’ where students made tea, chatted and sang songs to make sure the campus did not become less woman-friendly after dark.

In the summer of 2018, JMI University also reversed the gains that had been made in curfew timings a few months ago, and issued new rules prohibiting hostel residents from joining any protests or signature campaigns.

The Panjab University battle

One of the great victories for women’s rights in recent times has been at Panjab University (PU), Chandigarh. The movement unfolded parallel to Pinjra Tod, and both campaigns expressed support for each other. The key difference is that the PU campaign was driven by elected representatives and does not make any disavowals about being political.

The president of the PU students’ union, Kanupriya (she uses one name) told this writer that curfews are not just restrictive, they also impose extra financial burdens on women.

When she arrived on campus in 2014, the curfew was 9 pm, and there were fines for any change in daily routine. “If I did not return to the hostel for a day, there was a Rs 50 fine,” Kanupriya explained, “If I went to my room and fell asleep at 9 pm, and missed roll call between 9 and 10 pm, I would be fined. There was a daily roll call that even PhD scholars had to submit to. It was just like jail.”

At the Hoshiarpur campus of the same university, the curfews were even more stringent. Residents had earlier complained about identity cards being confiscated if they were late returning to hostel, and in 2017, the women could not leave campus at all for over a month because their identity cards had been taken away for renewal.

In her first year at university, Kanupriya was too nervous to join sit-ins. In 2015, there had been a movement to allow 24×7 library access. The library was technically open to women at night, but the rule was not being implemented since all the girls were locked inside.

Encouraged by her seniors, Kanupriya was one of the first girls to go to the library at night to ensure that their right to library access was actually implemented. “At the time, we heard questions like: ‘But how will a girl come to the library?’ As if she had no legs to walk on!” she said.

Three years later, Kanupriya said, the atmosphere had changed. Female students would often go to the library at night to study in groups. When she won the students’ union election as a representative of Students for Society, she decided that if there was one thing she was going to fight, it was the idea that women had to be locked up to ensure their safety.

The 2018 movement began after an instance of sexual harassment. The administration’s response was to suggest that another grille gate be installed in front of the girls’ hostel. Kanupriya was furious. “A watchman sitting outside can’t do anything about the gerhi culture, where groups of men go around town on bikes and cars, looking at women, passing comments,” she said.

When Kanupriya put forward the demand that women must be free to enter and exit hostels at all times, the authorities initially told her that she was free to leave if she did not like the rules. Next, they offered 15-minute extensions to curfew hour, then half an hour, and so on. When negotiations broke down, the protest began.

At 9 pm on the night the protest started in 2018, the police showed up. Kanupriya recalled being worried because she saw more cops outside than women.

“We have all sorts of fears,” said Kanupriya. “Careers will be ruined. Photos might appear in the papers. Parents pressuring girls to quit.” She need not have worried. At 9:30 pm, there were more girls outside than cops. Eventually, about 750 girls defied curfew to stay outdoors between 9:30 pm and 12:30 am.

Students of Panjab University, Chandigarh, protested for 48 days in 2018, seeking 24 hour access to their hostels. The administration ultimately agreed to the demand.

For 48 nights, the protestors slept outdoors. Others showed support by bringing spare mattresses and blankets, as Kanupriya herself had done when she was younger and worried about what Mummy-Papa would say to her sleeping outdoors. In 2018, her parents knew what she was doing. They also knew she would not quit the protest to visit home on Diwali. Her mother told her what her father had said: baithi hai to kuch le ke hi uthegi (If she’s sitting in, she’ll get up only after she’s achieved something). “Diwali came and went,’ she said. “Gur-parab (a religious festival) came and went. We had exams. But the girls did not give up.”

The administration was not giving in easily. The refrain was: If something happens, who will be responsible? Kanupriya had had enough of that: “I told the security officer to quit. The UGC says that you have to provide security, not that you lock us in. I said, give your job to me, then I am responsible for security.”

Eventually, a decision was taken to allow students to come and go at all times, with one rider: women stepping out after 11 pm would log their exit in a register.

Delhi University has proved to be a harder nut to crack. When asked how the PU movement had succeeded where others have not, Kanupriya said that in order to build sustained pressure, demands have to be backed by a popular mandate. Panjab University was persuaded because she and Students for Society (SFS) could claim to speak for all students, men and women. Political organisation was necessary.

A Pinjra Tod protest held on October 8, 2018, at the University of Delhi gates to protest hostel curfews. The university has not responded sympathetically yet, and rules vary across affiliated colleges.

Evolution and relationships

Since Pinjra Tod is not linked to any political organisation, it has found support across colleges and is fed by diverse energies: teenagers from small towns with no experience of activism as well as doctoral scholars with political views. A few years ago, Tewari said, she saw all politics as bad. “I didn’t have the imagination to think beyond electoral politics. I used to think of it as an industry, an enterprise. Now I see it as the framing of a political vision.”

Nevertheless, it is true that Pinjra Tod cannot claim to speak for all students of Delhi University, and, therefore, cannot pressure the administration on their behalf. It has also taken a while for the collective to be taken seriously by other groups. They have been told that curfew hours and other matters are not serious issues, that they should focus on caste and class struggles instead.

Pinjra Tod activists said these issues are not mutually exclusive. They pointed out that Delhi University library workers supported their push for night access to libraries, and when library workers had protested, Pinjra Tod had extended support.

In 2018, the collective also issued a statement against the “criminalisation of working class lives”, after the LSR hostel warden allegedly refused to leave the hostel gates open because “delivery boys come to deliver food to teachers who live on campus”; the implication was that delivery boys posed a danger to students.

Activists also complain that mainstream media distorted their language. “We use words like manuvaad in our communication but certain media outlets changed it to ‘gender justice’, said Narwal. “One news website republished our note but dropped the words ‘brahmanical patriarchy’.”

On the other hand, the collective is facing criticism from within. Nine students publicly distanced themselves accusing “the leadership” of not adequately addressing caste, class, religion and race. While there is no formal hierarchy, the statement put out by the group of nine said they felt excluded from decisions, and the organisation was dominated by upper-caste women.

Pinjra Tod responded: “Any such experience was not inevitable, and must be attributed to the lack of political maturity and capacity of the movement collectively, and all those participating in it individually. Those of us who remain in the movement today, stay here committed to the responsibility of continuing to learn from our struggles, in building firmer solidarities.”

For now, it continues its work online, keeping track of campus protests and documenting them through social media.

Meanwhile, the Indian judiciary appears confused about interpreting constitutional freedoms guaranteed to women.

In March 2019, the Kerala High Court ruled that a woman’s rights cannot be “compromised” based on parental consent. The judgement was based on a petition by two former students at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur. They moved court against hostel rules, which, they argued, violated their fundamental rights. While the court ruled in their favour, it refused to interfere with curfew hours, leaving that to the discretion of the college authorities.

It was not until the women threatened to go on strike that Sree Kerala College extended curfew from 6:00 pm to 8:30 pm and not before it called parents to a meeting where they reportedly were narrated stories of attempted rape when girls stepped off campus.

Many campuses demonstrate a similar reluctance to accept changes that should be made in good faith and with respect to the law, said Pinjra Tod members. RIE campuses in Mysore and Shillong have not extended curfews since the women have not yet launched protests.

On the contrary, on April 10, Pinjra Tod reported developments at the Mysore campus, alleging a student had been summoned to the principal’s office for wearing a sleeveless dress. Pictures were taken without her consent, and eventually her parents summoned. At the Ajmer campus, the curfew extension question continues to be discussed with parents although most students are older than 18. At the Bhopal campus, a student diagnosed with depression had applied for a week’s leave and was asked to vacate the hostel.

Although Panjab University, Chandigarh, agreed to unrestricted hostel access, the regional centre in Hoshiarpur refused to follow. That would require another protest.

On the eve of International Working Women’s Day, the Pinjra Tod page was updated with news that women at the Hoshiarpur campus had leaped through their hostel windows to defy the curfew. A week later, unrestricted hostel access was allowed.

Another cage was broken.

(Zaidi is a freelance writer and the author of “3 Plays”, “Gulab, Love Stories # 1 to 14”, “Known Turf: Bantering with Bandits and Other True Tales” and the editor of ‘Unbound: 2000 Years of Indian Women’s Writing’.)

Courtesy: India Spend