Morthala (Sirohi district): When the women of this southwestern Rajasthan village sat down to eat, it was usually after the rest of the family had finished its meal — the men first, the children next and themselves last.

This is a common practice in many Indian households, but among the rural poor it makes women and children, some of the weakest in the world, hungrier and sicklier, sparking a cascade of slow development, eventually implicated in holding back national economic progress.

“Particularly among the rural poor, food distribution in households is not based on need,” reads Right to Food in India, a 2003 paper of the Centre for Economic and Social Studies, Hyderabad. “The breadwinner gets sufficient food, the children get the next share, and women take the remains.”

A two-year-old project in Rajasthan used an unusual strategy to break this pattern among poor tribal communities in the southwestern district of Sirohi and eastern district of Banswara. Instead of simply increasing their food supply and access — the standard approach for dealing with malnutrition — it attempted to break the tradition of prioritising men’s needs first.

“We were advised to serve meals only after all the family members are seated so that everyone gets served equally and we discuss food,” said Rukmani (who uses only one name), one of the project beneficiaries.

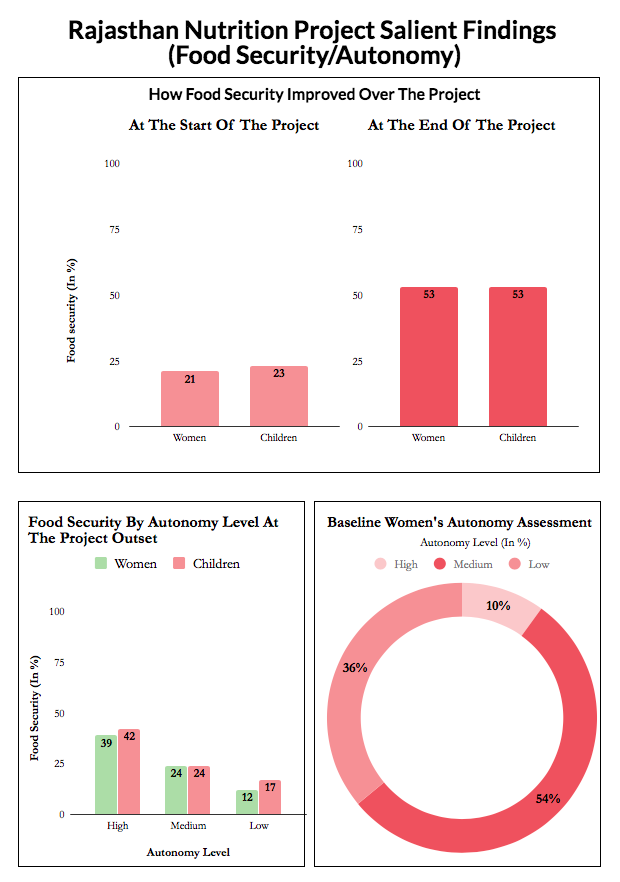

Behind this strategy of the Rajasthan Nutrition Project, launched in 2015, was a baseline survey of 403 women. It revealed that those with a lesser say in running their household were more likely to have less food for their children and were themselves vulnerable to malnutrition.

Malnutrition is one of the leading causes (about 50%) of all childhood deaths in India, and malnourishment at an early age can lead to long-term consequences, as it affects motor, sensory, cognitive, social and emotional development, IndiaSpend reported in July 2014.

“Stunted children (low height for age) face a lifetime of lost opportunities in education and work,” said a global study called End of Childhood Report 2017. “They are also more likely to succumb to illness and disease, and can die as a result.” Only one child in 10 in India gets adequate nutrition, IndiaSpend reported in May 2017.

So, the Rajasthan campaign, executed by Freedom from Hunger India Trust and Grameen Foundation, both nonprofits, through local partners Pradan and Vaagdhara, made women more health and nutrition-aware and sensitised their husbands to gender equality.

Source: Freedom from Hunger India Trust and Grameen Foundation

“We chose to address intra-household food consumption disparity — the fact that in one household alone, the women and children could be food insecure while the men are food secure,” said Saraswathi Rao, CEO, Freedom From Hunger India Trust.

Over two years, the project has touched the lives of 30,000 people and among the 403 women who were sampled, more than doubled the number of women and children who always have enough to eat.

Before the intervention, 31% women had reported that their husbands alone decided how much food to serve the family. After being told to make decisions jointly, no more than 3% of men continued to take this call alone, while the number of couples making joint decisions increased from 12% to 19%. Also, 53% households reported eating more meals together as a family.

Why better nutrition for women needs a change in attitude

The Rajasthan Nutrition Project’s approach is significant in another respect. Economists have long wrestled with a problem often referred to as the India Enigma: Despite greater economic progress India’s child health indicators fare worse than that of sub-Saharan African nations.

India has more malnourished children than sub-Saharan Africa, IndiaSpend reported in May 2017. Indian babies are more than twice as likely to have lower birth weights than those born in sub-Saharan Africa, 28% to 13%, IndiaSpend reported in November 2016. Low birth weight is the single largest predictor of undernutrition, write S Mahendra Dev and Alakh Sharma in a 2010 Oxfam publication.

The problem, Dev and Sharma said, could be empowerment. “Women in South Asia tend to have lower status and less decision-making power than women in sub-Saharan Africa,” wrote the authors.

So, the solution does not appear to lie in increasing household food supply and access to food—as the government does through the Public Distribution System and Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), respectively, as a baseline study conducted at the start of the project confirmed. The ICDS is a national programme that provides medical services to preschoolers through a local anganwadi (creche).

Interviews with 403 women revealed who made household decisions about food, mobility and communication. This, in turn, was found to closely correlate with their own and their children’s food security. Nine in 10 were married, of tribal origin and had an average of 3.21 children, including at least one under the age of two, and a third were from families with monthly income Rs 2000-2500.

Among the women who reported having greater autonomy, 39% respondents and 42% of their children had enough to eat. Only 12% women with lower levels of autonomy and 17% of their children reported having enough to eat.

| Rajasthan Nutrition Project Salient Findings | ||

|---|---|---|

| How Some Empowerment Indicators Improved During The Project Period | ||

| Criteria | At the start of the project | At the end of the project |

| Received benefits from the ICDS centre in the last 12 months | 61% | 93% |

| Received supplementary food from the ICDS centre | 84% | 90% |

| Child with diarrhea was given more to drink | 7% | 42% |

| ORS used to treat diarrhea | 34% | 84% |

| Delayed medical treatment for children in past year due to cost | 55% | 16% |

| Delayed medical treatment for herself in past year due to cost | 62% | 28% |

| Who breastfed within 1 hour of birth | 47% | 83% |

| Who exclusively breastfed first 6 months | 27% | 36% |

| Feels very confident that she can afford nutritious foods for all of her family | 15% | 33% |

| In the last 12 months, was afraid of husband/partner (% most of the time) | 17% | 5% |

| Set aside savings for health in past 6 months | 65% | 80% |

| Saved or set aside any money to cover future food expenses in past 6 months | 62% | 80% |

| Husband takes decisions on how money should be spent | 71% | 16% |

| Couple takes decisions on how money should be spent | 24% | 51% |

| Husband takes decision on whether wife seeks healthcare for herself | 69% | 28% |

| Couple takes decision on whether wife seeks healthcare for herself | 27% | 55% |

| Husband takes decisions on food purchases | 37% | 18% |

| Couple takes decisions on food purchases | 25% | 49% |

| Husband takes decision about how much food to serve family members | 31% | 3% |

| Couple takes decision about how much food to serve family members | 12% | 19% |

Source: Freedom from Hunger India Trust and Grameen Foundation

Women who had a greater say in household decisions were more likely to use government health services, breastfeed their children and enjoyed a better relationship with their husbands.

The study revealed that any effort designed to improve food security and nutrition had to aim at improving women’s autonomy and decision-making within the household, Kathleen Stack, executive vice president of the Grameen Foundation said.

The other benefits of abandoning gender hierarchy

In a one-room tenement in Morthal, with a television blaring in the background, a group of women were talking of what they had learned: How control over nutrition, health and household finance helps their families become healthier.

Zuhra Bano and Meera Gujjar, leaders of local Self Help Groups (SHG), were the most vocal. With 1,250 other mostly illiterate leaders of SHGs, they had signed up for training under the nutrition project.

The 1250 trained Self Help Group (SHG) leaders were called Community Nutrition Advisors, and given the job of imparting information to their SHG members and the women’s husbands. They also held rallies to spread the word.

Having qualified as community nutrition advocates, Zuhra, Meera and the other SHG leaders disseminated their new knowledge to their group members—women like Santosh, Hemlata, Rukmani.

One of the project aims was to increase the food available for the sample set of women and children. This was measured by moving them up at least one point on a four-point scale.

| How The Rajasthan Nutrition Project Defined Food Security | |

|---|---|

| Status | Meaning |

| Food secure | Have enough food and of the kinds of nutritious foods we want to eat |

| Food insecure without hunger | Have enough food but not always nutritious food |

| Food insecure with moderate hunger | Sometimes not enough food to eat and was sometimes hungry |

| Food insecure with severe hunger | Often not enough food to eat, was often hungry |

Source: Freedom from Hunger India Trust and Grameen Foundation

Women were also encouraged to use the food distributed to pregnant and lactating women and young children under the ICDS. Some women had not used this service because they did not know of it, others because their families restricted their movements.

“We never knew that the anganwadi provides children (aged 3 to 6 years) a free daily meal, a variety of meals like daliya (porridge) and khichdi (a rice and lentil preparation), and take home rations for infants,” said Meera, the SHG leader.

The Rajasthan Nutrition Project, an initiative in Rajasthan’s Sirohi and Banswara districts involved training 1250 mostly illiterate Self Help Group (SHG) leaders in health, nutrition and managing household finances. Here, Meera (in green), a SHG leader, is seen with a few members of her SHG, with who she shared her learning. The 1250 SHG leaders reached out to over 8000 women, and through them, touched the lives of 30,000 people.

Having learned of what was available, the women of Morthala wondered if they would be permitted to walk to the nearest anganwadi, a couple of kilometres away, in the neighbouring village.

To address this social constraint, community facilitators like Baldev Kumar, also trained under the project, and community nutrition advocates conducted gender dialogues to explain to husbands why it was important for couples to make decisions jointly.

After these conversations, more than twice the number of women were permitted to visit a market or healthcare centre than before, increasing the use of anganwadi services by 32%. The number of couples taking joint decisions about buying food also doubled.

Ensuring dietary diversity in a few, cost-effective steps

To improve their family’s nutrient intake, women were advised dietary diversity, especially to eat more fruit and vegetables. This was unthinkable for many of the tribal women, who had no money to buy extra food.

“So, we sourced seeds from local government agencies and helped them create kitchen gardens, even those with limited water supply started using waste wash water to grow a few vegetables,” said Baldev.

Women now reported consuming an average of three additional foods a day. Their intake of green leafy vegetables increased 344%, their consumption of yellow/orange coloured veggies rose 940% and their milk intake rose 70%.

Nutrition tips the women took to implementing included guidelines such as “cook in an iron pot” and “make more nourishing rotis (Indian flat bread) by mixing a couple of grains like wheat, corn and pearl millet instead of using only wheat” and “breastfeed your children in the first hour after birth”, reported Zuhra and Meera.

Among the 403 study participants were 21 pregnant women, an intentional inclusion to gauge how women’s autonomy affected breastfeeding.

When the women were first interviewed, it turned out that those with a say in their household finances were more likely to report exclusively breastfeeding their child for six months.

Over the course of the engagement, the percentage of new mothers who breastfed infants within the first hour of birth increased from 47% to 83%.

Autonomy empowers rural women to deal with illness more promptly

Having been shown how to make Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) and to keep a child with diarrhoea well hydrated, the number of women who had treated a child with diarrhoea with ORS increased by 140%—from 34% to 84%.

“Now we take care of diarrhoea ourselves by making ORS,” said Meera, the SHG leader

Better knowledge of health services at the anganwadi encouraged more women to promptly seek healthcare for themselves as well as their children.

Savings on health increased from 65% to 80% while 52% women reported an overall increase in savings.

“Now we put aside a little money every month for our health, just in case we need it,” said Zuhra.

Zuhra Bano (in orange), a Self Help Group (SHG) leader, signed up to be trained as a Community Nutrition Advisor, which meant she would share health, nutrition and household finance information with members of her SHG and interact with the women’s husbands to tell them how important is it to make decisions about health and food jointly.

Make the community a part of the solution

“We found the methodology effective because it involves the community; making local women a part of the solution always works better than advocacy by an external agent,” Roli Singh, secretary of Rajasthan’s department of women and child development told IndiaSpend.

“Also, the initiative is cost-effective, and the kitchen garden component to enhance the supply of fresh and nutritious food can be made more effective by synergising it with a livelihoods initiative and agriculture extension schemes,” said Singh.

To involve the community even more closely, Singh would also like the manufacturing, packaging and supply of supplementary nutrition to be outsourced to SHG clusters with experience in health and nutrition advocacy.

At recent national and state level consultations in Delhi and Jaipur, Arun Panda, (then) additional secretary and mission director, National Rural Health Mission, released a policy brief and a technical guide based on the Rajasthan project.

Prepare nutritional dos and don’ts in simple language, including Hindi, and share these with the ministry of health and family welfare to be disseminated in other states, Panda requested the Freedom From Hunger India Trust. “Simple and cost-effective solutions can easily be understood, adopted and sustained,” he said.

Back in Morthala, Meera and others’ lives are changed forever. Thanks to a small change in their mealtime routine.

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)