Paddy farmer Nanasaheb Armo (58) of Ghatbarra village in northern Chhattisgarh amid the remains (left) of what was once the Hasdeo Arand forest, which was used for generations by his Gond tribe and a part of which is now an open-cast coal mine. The village, in mineral-rich Sarguja district, is the first in India to have its community forests rights revoked, within two years of being granted. The same forest (right) before mining rights to 1,898 hectares were granted to a Rajasthan state power utility, on behalf of whom an Adani company now mines coal.

Thousands of trees were chopped and strewn across land larger than a football field. The silence was punctured only by the noisy beeping of a hydraulic mining shovel, at work in a nearby open-cast mine. Armo and his Gond tribal community knew this forest to be theirs for generations– and to which they were given official titles five years ago.

But their subsequent dispossession and anger is a story that explains how mineral-rich forest land in tribal areas is being taken back by the state of Chhattisgarh. With 31% of its population tribal–more than any other large Indian state–the unrest now threatens the re-election prospects for a three-term Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government.

In the first phase of its assembly elections on November 12, 2018, Chhattisgarh witnessed a 70% voter turnout in tribal areas. If the second phase registers a similar higher-than-normal turnout on November 20, 2018, it could reflect the discontent over the slow progress of individual tribal land claims–more than half of which have been rejected–and the particular struggle for community claims in the mineral-rich north.

“I heard in Delhi, the government planned to cut 1,700 trees, and the Supreme Court stopped them,” said Armo. “Do they even know what is going on here?” Next to him, Janandhan Singh Purte (38) joined in the conversation. “These trees have existed before us,” he said. “They gave us everything we needed. Now our grandchildren, their children and the generations after them will never know what it is like to grow under their shade.”

The Gonds are one of Asia’s largest tribal groups, varied in their livelihoods, from hunter-gatherers to regular, modern occupations. Here in Sarjuga district’s Ghatbarra village in the north of India’s most tribal state, they live almost exclusively in rural areas, which are home to 98% of Chhattisgarh’s tribal people, or Adivasis.

It was in recognition of this close-to-the-forests-and-land existence that Adivasis were to be given land rights over the forests that make up 44% of the state’s area. In 2006, Parliament recognised “historic injustice” in denying traditional rights over forest resources to forest dwellers nationwide and passed the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, or FRA in short. In 2013, five years after they applied, the Gonds of Ghatbarra were granted their claims.

Two years later, that claim was revoked.

How a land title is revoked

In 2014, the Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam Limited (RVUNL), a Rajasthan state-owned power utility, contested the legitimacy of Ghatbarra’s rights, on the grounds that the government had already granted it mining rights for the same area in 2011. That was when the ministry of environment & forests (MoEF) cleared the handover of 1,898 hectares–63 times the size of New Delhi’s Connaught Place business district–of forest land. Adani Mining Private Limited, a subsidiary of Adani Enterprises Limited, one of India’s largest conglomerates, controlled by one of its richest men, Gautam Adani, runs the mining operations for RVUNL.

The revocation of Ghatbarra’s community rights to its forest in 2015 was the first such move in India. The Chhattisgarh government argued that villagers were misusing the rights to obstruct mining work around the area. The MoEF revalidated RVUNL’s clearance in 2015, claiming due process was followed: Public hearings, and approvals from the gram sabha, or local government, under the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas Act (PESA), 1996, and environmental clearances under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006.

Residents of Ghatbarra, like their neighbours in the villages of Salhi, Hariharpur, Basan, Parsa, Kante, Fatehpur, and Saidan, assert that the forest has been their home for generations. Only Ghatbarra received community forest rights and its people pointed out that the FRA recognises rights of all forest dwellers residing in the area up to the day before the Act came into being — 31 December, 2007. They denied ever approving the company’s mining plans at any of the public hearings held in 2009, or recently in 2016 for its expansion plans.

“We have never attended any hearings–the minutes of these meetings are fabricated,” alleged Ram Lal (35) of Salhi village. “The recent 2016 hearing was managed. They invited a few people from each village, bribed them with drinks and money and asked them to sign a paper.”

On November 16, 2018, IndiaSpend reached out to Adani Enterprises for their comments on the Ghatbarra case and the allegations put forward by villagers. On November 19, 2018, the company responded saying they are working on a response and that they will share the same once they are ready. We will update the story when we receive the company’s statement.

Saransh Mittar, the Sarguja district collector, who is responsible for all local administration, said he was new to the area. “Right now, the elections are taking up most of our time, so I haven’t actually visited the area or got to know the minor details yet,” Mittar told IndiaSpend.

While the Ghatbarra villagers’ case over community forest rights is pending in the Chhattisgarh High Court, the environment ministry issued a new environmental clearance to RVUNL on August 10, 2018, to expand mining operations, from 10 million tonnes annually to 15 million tonnes. Over a fortnight later, human rights lawyer and social activist Sudha Bharadwaj, who was working on the villagers’ case, was arrested by the Pune Police on charges of having links with the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist).

“We have all been arrested at some point in the last few years,” said Balsaiku Ram (48), a member of the Salhi Block Development Council, the local government council of a village near Ghatbarra. “Whenever we try to protest, hold the company accountable for what has been promised, they use the law to silence us.”

The BJP’s sliding popularity in tribal Chhattisgarh

Carved out of Madhya Pradesh in 2001, Chhattisgarh is slightly larger than Greece with a population comparable to Australia. About 44% of its land is forested, under which lie some of India’s richest mineral deposits: Coal, iron ore, dolomite, bauxite, limestone, quartzite and tin.

These forests are concentrated in tribal lands, where 7.8 million Adivasis live. Barely 2% of Chhattisgarh adivasis live in urban areas. The tension roiling their lands is reflected in the BJP’s dwindling popularity among the state’s tribal peoples.

During state elections in 2013, the BJP won 11 of 29 seats reserved for scheduled tribes (STs), eight fewer than in 2008 when it won 19 (of 90 in the state assembly). Among seven constituencies with a tribal population of more than 70%, the BJP won just one seat in 2013, compared to five in 2008.

With farm distress evident across Chhattisgarh, as IndiaSpend reported on November 16, 2018, and pre-election surveys predicting a close contest, the constituencies reserved for tribals could prove to be electorally important.

As Raman Singh, the BJP’s longest-serving chief minister, now seeks his fourth term, the simmering frustration over land rights among his state’s indigenous peoples could impede his political future.

As literacy grows–the state’s literacy rate among scheduled tribes went up from 52.1% to 59.1% between 2001 and 2011–and awareness spreads about the FRA, so does discontent.

Village conversations: From cattle grazing to forest rights

Villagers of Hariharpur and Salhi, in Sarguja district, northern Chhattisgarh, are still waiting for community forest rights, under the Forests Rights Act of 2007. Along with neighbouring Ghatbarra, these are the three villages most affected by the open-cast coal mine run by Adani Mining Pvt. Ltd.

Off the dusty, rugged Ambikapur-Raipur highway, under-construction since 2016, past rolling fields of rice, vegetable patches and thatched-roof houses decorated with vines of yellow cat’s claw flowers growing wildly over wooden fences, villagers gathered in the courtyard of farmer Meghnad Marabi (65)’s home.

“Years ago, when I was a boy, we used to meet once a week and discuss village matters about who will take the cattle grazing, who will collect forest produce, who will till the land,” said Marabi of the Gond tribe. Dressed in a cream vest and white dhoti, with a long necklace of red beads, the village elder sported a thick, white mustache and white spots painted on his forehead, wrist and arm. “Every day, all we discuss is vanadhikar (forest rights) and pattas (titles).”

Since the FRA came into force on December 31, 2007, India has distributed about 1.87 million titles over 14 million acres–equivalent to the size of Himachal Pradesh–of forest land nationwide, according to May 2018 union tribal affairs ministry data.

After Maharashtra and Odisha, Chhattisgarh ranks third in number of land titles distributed. But parsing the data revealed that 53% of these claims are either rejected or still under process.

Of 887,665 title claims, Chhattisgarh’s government has issued 416,359 titles across 2.7 million acres, which is 7.8% of the state’s area or 18% of its forest area, according to an IndiaSpend analysis of title data.

“We estimate that nearly half the tribal population has not even demanded their rights yet,” said Alok Shukla, convener of the Chhattisgarh Bachao Andolan (CBA), a broad nine-year-old coalition of 22 civil rights groups. “Approximately 1.5 million individual rights should have been claimed, titled and distributed, so the implementation rate of a state with (India’s) largest forest cover and highest concentration of tribals is much poorer (than others).”.

Further, 95.6% of titles distributed relate to individual forest rights (398,181). Community forest rights–central to the agency of Adivasi tribes as they recognise the authority of the gram sabha (village council) and responsibility to protect, manage and conserve its customary forests–account for the rest 4.4% or 18,178 of 416,359 titles distributed.

“It is not that adivasis in this area do not have community forest rights,” said chief conservator of forests for Bastar division, Nitin Nonhari. “Across the state, all traditional forest dwellers are given rights through the joint forest management (JFM) committees. Everyone above the age of 18, regardless of social group, can be a member. Through the JFM, villagers are empowered to collect and monetise minor forest produce, so it is the same as granting community forest rights.”

But JFM committees are controlled by the forest department with no rights to indigenous people, the charity Oxfam said in a 2016 report assessing the implementation of forest rights in India. “FRA supersedes JFM, or similar arrangements, by vesting management rights and empowering the gram sabha to govern all CFR areas,” the report said.

Our analysis of district-level data showed that fewer claims were rejected in the southern districts that report Maoist influence and violence: Bastar, Dantewada, Sukma, Bijapur and Narayanpur. In the North, where mining operations are widespread, districts such as Sarguja and Korba–called the power capital of India, home to 14 thermal power plants and accounts for 17.3% of India’s coal production–reported the most rejections.

The northern district of Bilaspur, home to SECL’s headquarters, vast coal deposits and fertile lands–it is regarded as Chhattisgarh’s rice bowl–reported the highest rejection rate at 74%.

Source: Chhattisgarh State Forest Department

Data as of December 2017

“We don’t know what is the exact situation in most of south Chhattisgarh because it is difficult for NGOs to reach the people in the on-going war with insurgents,” said the CBA’s Shukla. “If we try to work with the people and hold the government accountable, we are accused of having Maoist-links.”

“The conflict for resources by private interests has not reached the south because of the ongoing war,” said lawyer Shalini Gera, who specialises in land conflict. “Where there is a conflict, we have found the government is more likely to reject claims.” Gera, currently with land rights NGO Maati, based in Kanker district, closer to central Chhattisgarh, was the co-founder of the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group in Jagdalpur, Bastar, in the south. It offered free legal aid to poor tribals embroiled in legal cases with the police, companies or government organisations. In 2016, the group was forced out of the area by local police.

As we moved to the north, the issues changed, but the hostility to the government remained.

In the industrial north, short-changed on land titles

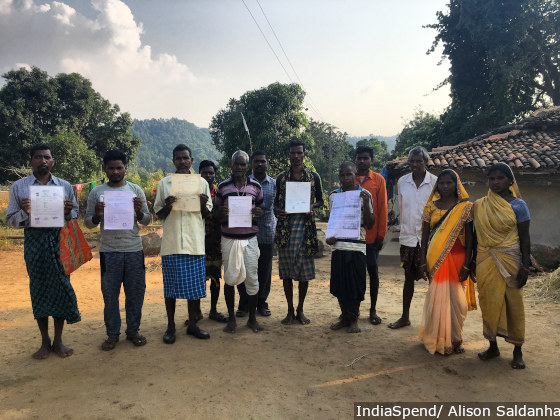

The Paharikorwas, a particularly vulnerable tribal group, of Govindpur village in Sarguja district, northern Chhattisgarh. Barely a quarter of 222 households in the village, have received titles–and to less land than they said is due to them.

Among Adivasis who received individual forest rights, for lands officially recorded as forests but actually occupied for habitation or cultivation, several villagers told IndiaSpend that the titles granted covered a much smaller patch of land than their claims.

For example, in Sarguja, Mangal Sai (38) of Hariharpur village received a fourth of the claim–two of 8 acres–he inherited from his father’s forest rights. About 10 km away in the neighbouring village of Ghatbarra, Rupan Singh Verma (45) and Srinath Markham (31) received titles for 1.5 and 0.86 acres, respectively, instead of 5 acres. “Most of us have got barely 0.5-2 acres, and nobody in the area has received more than 3 acres,” said Verma.

About two-and-a-half hours north of Ghatbarra, past rolling paddy plantations, rugged roads lead to Govindpur village, where 92 of 222 households of the Paharikorwa tribe, a particularly backward tribal group, applied for forest titles in 2013 under the FRA, so they could protect themselves against land grabs by other tribal groups in the area.

So far, 60 families, or a quarter of Govindpur’s households, have received titles: 15 have received titles for more than 1 hectare (2.47 acres), according to NGO Chaupal Gramin Vikas Prashikshan Evam Shodh Sansthan (Rural Development Training and Research Institute), or Chaupal in short, based in Ambikapur city, Sarguja district. The NGO used satellite imagery to help villagers frame applications to claim titles that matched their land use.

“As in several other areas, the Paharikorwas of Govindpur were unaware of how to apply for rights over the land under the new law, until they saw their land getting encroached on,” said Chaupal president and adivasi rights activist Gangaram Paikra. “We found that in many cases, forest titles are bestowed haphazardly. Who gets how much land is a lottery, there is no logic behind why one family got more than the other.”

Shukla of the CBA said they found cases where titles were given to land covered by ponds and several titles issued for the same plot of land.

Such inefficiency has sparked protest. On August 23, 2018, 32 Adivasi villages of Sarguja went on a 11-day hunger strike to protest the slow implementation of the FRA. For the first 10 days, the government said nothing.

“When the strike started to make headlines, the district magistrate visited the protest site and threatened to arrest us,” said Paikra, one of the chief protest organisers. “When he saw the villagers would not budge, he requested we wait to speak to the new collector. We’ve been waiting to hear from them since we first applied (for forest rights) in 2012.”

Still, protestors of the 32 villages asked the new collector–Saransh Mittar, quoted previously as saying he was “new to the area”–for a solution.

“He appealed we wait till the state elections are over,” said Paikra. “So now, we are waiting.”

In the south, they get land titles without asking

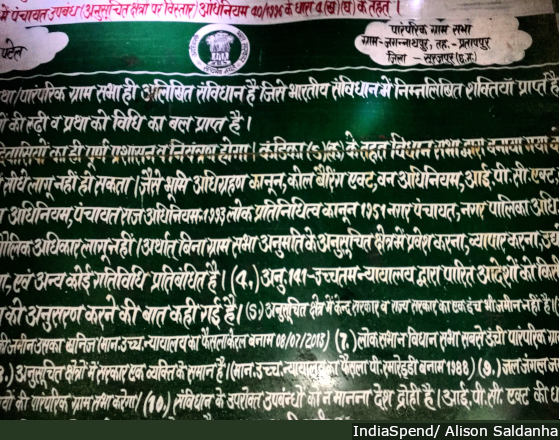

Recently, in 2015, villagers of Madanagar village in Pratappur, Surajpur, a northern district bordering Madhya Pradesh, installed an 11-ft high, 6-ft wide, green metal board with sections of the Constitution and laws relating to local panchayat rights and Adivasi rights. This is a local variation of what is called the pathalgaddi (stone order) movement, a silent protest that began in Jharkhand in 2013 and has since spread to the nearby northern borders of Chhattisgarh.

“The RSS-BJP try to dismiss pathalgaddi, calling it a communal conspiracy by Christian missionaries to convert Adivasis,” said Phulgence Xalxo (26), leader of the protests against the mining operations of South Eastern Coalfields (SECL), a subsidiary of state-owned mining giant Coal India Ltd. “But this is not about religion. We just want our rights.”

Madanagar has not received any community forest rights, and has little hope of receiving community rights since mining began in 2006, a year before the FRA came into force on December 31, 2007.

Sections of the Constitution, the Forest Rights Act and the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas Act, painted on a green board and erected near villages in Surajpur district, northern Chhattisgarh. Villagers are yet to receive individual or community forest rights.

Down south in the tribal-dominated districts of Dantewada and Bastar–a verdant region rich with flora, fauna, waterfalls and over 100,000 police and paramilitary forces battling Maoists–several Adivasis we met revealed they had received land titles in 2012, a year before the previous state assembly elections.

They had never applied for these titles.

“Adivasis here are uneducated and illiterate, so while mapping the area, we carried out the work ourselves, taking into account the encroachment and land-use patterns,” R R Patel, range officer of the Bacheli forest division, Dantewada told IndiaSpend.

In the south, locals, who struggle to eke out a living, were not concerned with land titles. This is an area with low literacy–51-64% compared to 67-81% in the north or 77-83% in central Chhattisgarh. Health and development indicators are also worse: 15.9% of Bastar’s children under five are severely wasted (low weight to height), indicating they suffer from malnutrition, compared to 7.1% of Sarguja’s children, showed 2016 national health data, the latest available.

Now, with mining companies turning their attention to the south, those land titles, enthusiastically granted by the government, could be a hurdle.

“We are already coming across cases in Kanker where officials regret issuing land titles over areas now marked for mining,” said Gera of Maati, the land rights NGO. “Ghatbarra may be the first case, but it is likely not to be the only one.”

Devils in the details, and a flood of companies

The issue of land and forest rights is tricky because despite the wide ambit of the law, tribals must prove they have lived in the area for generations and prove they are indeed tribals–some are scheduled castes and other backward castes, groups that may qualify as “other traditional forest dwellers”. In some cases, officials allege land-grab attempts.

In Dantewada’s lush Bailadila mountain range–under which lies one of the world’s largest high-quality iron-ore deposits–not a single forest-land title has been distributed under the FRA law, forest officials told IndiaSpend.

“The soil is bad for plantations, the vegetation is shrubbery and nobody can use land anyway, so there is no meaning in giving away land titles for this area,” R Ratnam Patel, district forest officer, told IndiaSpend. He said a portion of the Bailadila range, rich in biodiversity, is marked as reserved forest area and kept out of the area reserved for mining.

Currently, the National Mining Development Corporation (NMDC), a public sector company, is the only company mining here. But as India privatises mining, others, such as Jindal Steel and Power Ltd, and Essar Steel Ltd, are entering the region. Critics said these mining rights clash with the FRA and the lives of indigenous people.

“The Forest Rights Act is meant to undo the historical injustices of the colonial era,” said former Congress union minister and former member of parliament Arvind Netam, a Gond tribal leader. “Yet, we find that even after 71 years of Independence, and more than a decade of the Act’s existence, we are still struggling with a despotic mindset as the government looks at these areas as its mini-fiefdom.”

A further marginalisation of tribals

Most households of Kudkel village in Sarguja district, northern Chhattisgarh, have yet to receive forest rights under a 2006 law. Without these rights, the villagers say, they cannot move beyond subsistence farming.

Poor implementation of the FRA further marginalises Adivasis, who are already among India’s poorest people, with five of 10 falling in the lowest wealth bracket, according to latest national data, as IndiaSpend reported on February 28, 2018. About 46% of adivasis were in the lowest wealth bracket, compared to 26.6% of scheduled castes and 18.3% of other backward castes.

“If we had the rights, we could at least start plantations and earn some money,” said Samturbai (45), a Gond resident of Kudkel village in the northern district of Sarguja. “Without the patta (title distribution letter), anyone can come take our land any time. Already, some city folk have come to this area to survey the land.”

In Hariharpur, Salhi and Ghatbarra, villages considered to be most affected by the Adani mines, villagers argued that the land they now had could not sustain them. RVUNL’s new environmental clearance says it must employ 1,805 persons (without specifying if they must be “project-affected persons”) and build local infrastructure. However, no more than two or three families from each of the three villages had jobs at the mines, according to local Adivasis.

“We need jobs, we thought they were going to give us work in the mines,” said Sahi block development council member Balsaiku Ram. “All they have done is brought their own people from outside the area and made a few of our work as security guards and toilet cleaners.”

On the outskirts of the village, we passed rows of low-rise buildings with fresh paint. A few kilometres ahead, a bus stop with seats and roof built of high-grade stainless steel, sits amid tribal houses. Clouds of dust rise from the rough, unpaved road.

“Whatever they have built, they have built for their own employees,” said Janandhan Singh Porte of Ghatbarra. “They don’t care about us.”

The mining and employment contradiction

The discontent in Ghatbarra echoes a national contradiction in poor states that seek rapid economic growth and the inadequate employment that such growth provides. In most cases, the locals do not have the skills that companies driving such growth require.

In Chhattisgarh, the gross state domestic product (GSDP) grew 6.7% in 2017-18 over the previous year. Industry and manufacturing, of which mining forms a major portion, contributed most to GSDP, 48%, but it employs no more than 5% of the workforce. The sector is expected to grow by 5.8% in 2018-19. The services sector, which contributed to 35% of GSDP, is expected to grow by 9.5% and employs 30% of the state labour force.

Agriculture contributes to 17% of the GSDP, is expected to grow by 2.9% but employs nearly 80% of the population. Of 3.7 million farm households, 76% were from the small & marginal class, according to a 2015-16 state report.

While the number of agricultural land holdings operated on by Adivasis rose from 1,105 to 1,243 statewide over a decade to 2016, the cumulative size of these holdings declined 5%, according to an IndiaSpend analysis of agricultural census data, indicating growing fragmentation of land holdings.

Further, despite the concentration of mining operations in resource-rich forest areas where Adivasis are found in greater numbers, they are least employed nationwide in mining work (3,010), compared to SCs (5,830) and OBCs (14,760), according to 2013 government data, the latest available.

A

A

river runs through the Semersot Wildlife Sanctuary in Balrampur district, northern Chhattisgarh. The river bed was once visible only in the summer. Now, in November, the river runs dry, an indicator of changing local climate.

In Sarguja, as in the other districts we journeyed through, locals said the lack of livelihood was compounded by changing climatic patterns–possibly linked to growing industrialisation–dying forests and a dwindling of what is called “minor” forest produce: Mahua flowers, fruits, tendu leaves, gum from the trees.

Usually, the monsoons arrive in Chhattisgarh in early June. In 2018, it came two months later, as July was ending. “Our whole field dried out, we barely got enough to survive,” said Phuleshwari (35), of Sarguja’s Govindpur village. “The forest is (also) dying. Earlier we used to earn at least Rs 10,000-12,000 from selling vanopach (minor forest produce). Now, we barely manage Rs 3,000-Rs 4,000.”

About 150 km to the northeast, in Balrampur district’s Sargawa village, every household (about 100) had a cow shelter with at least seven to eight cows. “Now barely two-three households in the village can afford to keep cows,” said Kesur Kausaliya, a 36-year-old farmer who cultivates paddy, and vegetables for subsistence and works as a labourer when food stocks run out. “There is little left for them to graze on, and they are too expensive to keep.”

Adivasis recognise their contribution in Chhattisgarh’s declining forest cover, which fell 12% over two years to 2017, according to this 2017 Forest Survey of India report.

“We also cut trees for forest produce, we know it,” said Phuleswari. “But the rate at which we did this, and the rate at which it is being carried out now, is far more than the damage we could do in decades.”

In hushed voices of disbelief, villagers said recent deforestation has not spared the sacred mahua (Madhuca longifolia) tree, a kalpavriksha or wish-giving tree, which nourished the first humans in Adivasi folklore. Used in most religious ceremonies, the mahua tree is never cut by Adivasis.

“Recently, for Dussehra we had to go looking for the mahua flower for pooja,” said Srinath Markham of Ghatbarra. ”Earlier we used to get it within a few minutes walk from the village.”

“They are cutting so many trees, don’t they hear the earth crying?” asked 65-year-old Meghnad Marabi. As he spoke, the earth shook several times that day from explosions at the nearby mines. The bamboo thatched roofs with clay tiles rattled, and locals pointed to a crack in the cement and brick walls.

“We have earthquakes here every day,” Janandhan Singh Porte said, grinning. “We understand what this is, but the animals don’t know what is happening. Earlier we used to see deer, jungle cats and bears. Now, even the elephants have changed their path.”

And so to the elections that will solve nothing

A child of the Gond tribe outside her home in Badrimau village, in Maoist-affected Bastar district, southern Chhattisgarh. Many villagers received forest titles without applying, but in the absence of government services and development, land titles and elections mean nothing, locals say.

With so much change and unrest, most villagers we spoke to appeared bewildered about questions about the elections.

“Nobody cares,” said Chamru Budu (45) of Nerli village in Bacheli, in the southern district of Dantewada. Moments after our conversation on November 8, 2018, less than 5 km away, Maoists bombed a bus, killing four civilians and one paramilitary soldier. Later that day, a few residents in nearby Bhasi village said they would support the BJP. “Maybe they will bring us development, improve the lives of the poor,” said Naturam Telang (24) with a shrug.

With little to no development under the BJP for 15 years, locals near the Kanger Valley National Park in Dhurwa, in neighbouring Bastar district, pledged support for the CPI (Marxist). The densely forested area–notorious for the Jeeram Ghati Naxal attack of 2013 that killed more than 25 senior state Congress leaders–is riddled with land mines and no signs of the government.

“Neither the BJP nor Congress have bothered to come visit us for years now,” said Sanna Muchaki (27). “We are still waiting for a water hand pump. This village will only vote for the CPI (M)–only if they are given a chance, will we get our rights.”

In Sarguja and Surajpur districts, where villagers are alert to the land-mining conflict at their doorstep, most Adivasis we met appeared determined to vote the BJP out of power, regardless of the alternative.

“BJP ka bahut ho gaya (enough of the BJP),” said BDC member Balsaiku Ram of Salhi in Sarguja district.

Yet, despite a palpable anti-incumbency sentiment, some are sceptical of a BJP loss.

Bhisheshwar Singh, a social activist of the Kawar tribe, referred to the government’s public distribution system, which offers 25-35 kg of subsidised foodgrain, a frequently cited success story (here and here). “My people are poor and uneducated,” said Singh. “We want our rights but how can we fight when our stomachs are empty?” Now, with more getting educated, we are urging them to demand their rights, ask more from the candidates, not be bribed by the murga (chicken) and mahua (alcohol) offered during elections.”

The BJP made no direct promise of implementing the FRA in its election manifestos of 2008, 2013 or 2018. The Congress, after enacting the FRA in 2006, only made mention of the Act in its 2018 manifesto, saying, “The Forest Rights Act will be completely implemented. As per the Act, STs, SCs, OBCs and general class will be given individual rights over natural resources, and gram sabhas will be given collective rights. The PESA Act will be fully implemented in tribal-dominated areas.” Like the BJP, the Congress also offers monetary incentives for forest produce.

Back in Ghatbarra, Gond farmer Armo said neither the BJP nor the Congress were concerned with Adivasi issues.

While the BJP government had revoked his village’s community forest rights, it was the Congress government in Delhi that had cleared mining in what were marked as “no-go” protected forest areas.

“Our leaders do not seem to understand the bond Adivasis have to their land, the trees, the earth,” he said. “We want development too. But give us our rights first. If you take away our land, our livelihoods, our future, what are you leaving us with?”

(Saldanha is an assistant editor with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend