Kashmir is not just land. It’s a land of incredible people. They are a people who have lived through years and years of conflict. They should have the rights to express their plight, without being answered with violence and restrictions on their freedom of speech.

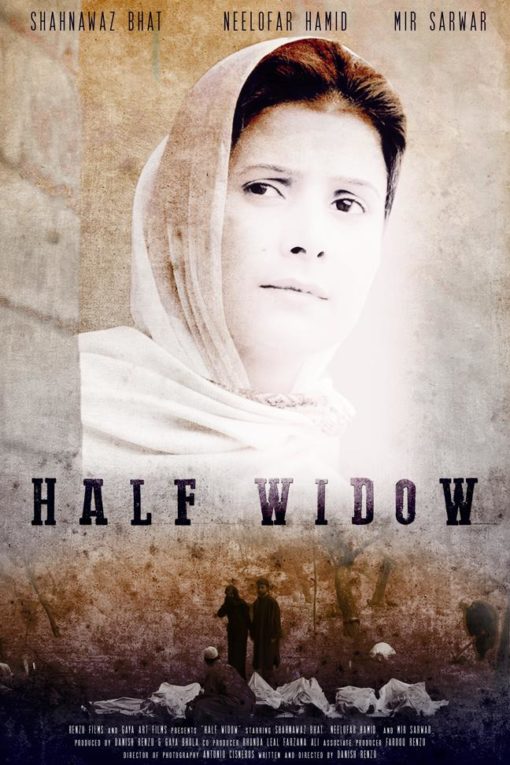

Image courtesy Danish Renzu

One can’t ignore them. One can’t simply shut them up, put them behind bars and stifle their voices. The true story of Kashmir and its people must be heard. Kashmiri voices cannot be suppressed and snatched away by force. It’s inhumane, unjust, unnatural and catastrophic at the same time. Yet it happened. And we can’t allow it any longer.

I left everything in the States to return to Kashmir, so that I could tell stories from Kashmir. I realised there was so much that hasn’t been depicted on the big screen. The culture, the music, the tradition, the language, and of course the pain of Kashmiri people who have been living through conflict for over seven decades. I had a dream to revive cinema back in the valley, so that stories of Kashmir can be heard. There were so many untold narratives, in every gully, in every kocha and in every mohalla. A story of a commoner who has been indirectly or directly affected by the conflict in Kashmir, and they have been forbidden to come out and tell their story. I realised cinema is the strongest medium to bring these stories to worldwide audiences: stories of local Kashmiri people’s day to day life, their hopes and their dreams. They dream for a conflict free Kashmir. They live in fear and uncertainty, under suffocating curfews. The hartals, demonstrations and killings continue. So many of them simply want to be able to have a meal with their family and just live another day. Their story must be heard.

As I explored more, I came up with my first feature Half Widow set in Kashmir with a cast of Kashmiri actors. Doordarshan still owed them dues from the last six years, so they were craving for work and recognition as artists. When I auditioned them, I was surprised by the emotions they carried and how they understood the nuances of tragedy and pain. We’re all connected by pure human emotion of pain and sorrow. All Kashmiris had it in them, and I hoped that this film could bring this out. They would be able to express this through dialogues and by no dialogues, through emotional scenes we crafted, by wearing their own clothes and by filming in real locations. I was able to capture plethora of real emotions while we shot the film with actors and non-actors. The story depicted the plight of a local Kashmiri woman who had lost her dear one in the conflict and was living a life of limbo, hoping that he’ll return one day, hoping for that day when she would hold his hand and go for a walk again. Perhaps he’s alive. But years pass by and there is no sign of her beloved. She lives in limbo and the only way she was able to express her plight is through writing. Through speech and by finding her voice, she is free again. She is able to forget the tragedy and pain and become complete again. Such was the narrative and such is the story of every Kashmiri. They’re people who’ve lost so much in this conflict: Their loved ones, their homes, their identity their opportunity to grow and learn and their opportunity to become a strong voice. I just realized they’re actually artists. They’re artists looking for a platform to express their plight and their values, what they’ve gained and what they’ve lost. They’re artists. They’re born to it.

The last few days brought back how the situation was in the 90s. Kashmir is disconnected from the rest of the world and nothing can go or come out of the valley at the moment. Troops are everywhere. Roads are closed. Voices are snatched away from the people and they’re not allowed to share their plight. Their birth-rights have been snatched away. They should be able to speak up and express their, their frustrations and their will. It’s their basic freedom of speech that should not have been snatched away from them. They’re a people who’ve suffered for too long. They shouldn’t have to suffer anymore. They will suffocate if not allowed to speak or to breathe or to be who they are. They are being caged, when they’re meant to be free. One can’t imprison a voice forever. It’ll find a way out. It’ll find a way and become a revolution. The artist in one can never die, and they eventually do find a way to perform. Their stories will be told.

The rise of artists from Kashmir in film, music and visual media industry is a revolution of its own. Artists from Kashmir have finally found a platform to vent out their pain, be it through pictures, poetry, films or music. In every cafe you’ll find Kashmiri youth holding a guitar, or a mic or even a camera. The rise of social media has only made it easier for them to share their talent with the world and tell their stories. The rise of artists in Kashmir has given rise to a new revolution. We hope that stories from Kashmir reach out to the world so that they understand what Kashmir is really about. How long are they going to be banned? The true story will definitely come out and it’s the core responsibility of filmmaker’s like us that we never fail the narrative of Kashmir. It must speak the truth yet to empower and free the artist in us all.

Bio: A native of Kashmir and alumnus of UCLA, film director Danish Renzu hopes to inspire a new generation of Kashmiri filmmakers to practice their art as a force for unity in the region. He has directed several short films including the award-winning “In Search of America, Inshallah” (2014). His first film Half Widow (2017) showcases the plight of a Kashmiri half widow and received rave reviews worldwide when it premiered at the Seattle International Film Festival. The Illegal (2019) stars Academy winning Life of Pi star Suraj Sharma in the lead. It explores the life of an immigrant in Los Angeles and his journey towards the American dream. His upcoming film Pashmina, set for release next year, tells the tales of several Kashmiri lives upended by decades of strife.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum