This is the elephant in the room, is it not? Was this “massive mandate” of the Lok Sabha elections 2019, the result of a free and fair election? Should we continue to discuss this outcome – the scale of the BJP victory, the numbers of seats, the margins by which seats were won – through political analysis alone?

Rather, has not political analysis of the election become inevitably deeply influenced by these margins and these numbers of seats, by the scale of the sweep? In other words, the analysis is of necessity post facto, assuming that these seats have actually been won fairly, and therefore represent the views of the electorate.

I found very revealing a story by two Reuters journalists who covered rural North India extensively. Mayank Bhardwaj and Rajendra Jadhav ruminate on how they could have gone so wrong in assessing the mood of the electorate. Although they say they never thought Modi would lose this election, it looked certain that he would return with a reduced majority. There was nothing they heard and observed on the ground that suggested the actual outcome. They conclude that next time they will travel even more, push their respondents harder, “be more aware of our limitations.”

Many seasoned journalists have the same sense of shock. But what if they were not wrong after all?

The day before results were announced, BJP told opposition parties to “accept defeat with grace”, after exit polls predicted a BJP sweep. Exit poll predictions were treated as the results themselves. Did the BJP leadership know something we don’t?

After Phase 6 of the elections, Amit Shah declared that after traveling across the country and gauging the mood, he was confident the party would cross the 300 mark. And so it did, by 3 seats. One did wonder at this mood that he gauged so accurately, given empty seats at rallies for Adityanath, Modi, and Shah in Gujarat, UP, Bihar, Chandigarh Karimganj, Guwahati. I list only a few.

Not to mention what preceded these elections – massive farmers’ agitations across the country, militant university campuses, country-wide demonstrations against lynch culture…

But Amit Shah knew almost to the number the seats his party would get. Even the RSS, with its massive ground-level networks, had no idea of what was to come, as was evident from Ram Madhav’s statement as late as May 7, saying the BJP will need allies to form government. (Or this could be characteristic Sanghi doublespeak, who knows.)

Let us begin this story then, with the infamous exit polls.

The dubious role of exit polls

The chances were very high that BJP would have emerged as the single largest party, and formed government with its allies in an NDA formation. Many serious political analysts expected this as a best case scenario both from the point of view of BJP, as well as its opponents.

However, exit polls though they varied, went much further, predicting a sweep by the BJP. The lowest number of seats for BJP predicted by exit polls was ABP- AC Nielsen with 267, just short of a majority.

Of course, at least one exit poll (India Today – Axis My India ) that predicted a BJP sweep (339 to 368) was rife with so many errors that very soon it took down seat-wise data from its site. Assembly constituencies in Uttarakhand were named as Lok Sabha constituencies; Congress shown as winning from Chennai Central, a seat it did not contest; the prediction for Sikkim Lok Sabha seat was changed.

Other exit polls too made huge mistakes:

News 18-IPSOS exit poll gave the Lok Janshakti Party between 5-7 seats while it contested only 6 seats in Bihar.

Times Now- VMR exit poll predicted that AAP would win 2.9% vote share in Uttarakhand while the party did not have a candidate from the state.

The methodology used in these polls was not clear. For instance, India Today said the question it asked was about popularity of the party, not about the candidate. Very much in keeping with the current wisdom that every vote for BJP was for Modi, not for the actual candidate. This has now passed into common sense, again post facto.

The methodology claimed by the India Today poll does not in fact stand up to any sort of scrutiny.

Never mind these details though, at the end of the day it was declared that India Today-Axis My India got the result “spot on” – although it was off by a minimum of 36 seats.

But to return to exit polls. What purpose do they serve? One, if they predict the right (not necessarily correct) outcome, then the Sensex is happy and makes money, satta bazars make money.

Two, how was it that despite such major errors and shoddy methodology, exit polls were largely correct in predicting the sweep? Where and how did they get the information they put out, and most importantly – was the intention of the exit polls to make the results seem credible?

Do doubts about the electoral process deny the validity of political analysis?

No, of course not. The very fact that the Opposition had to unite all over the country in different kinds of alliances if they were to defeat the BJP tells us that there are significant long term shifts in India that we need to recognize, not the least of which is the power of Hindutva that the RSS has been working on steadily for a hundred years, and the discourse of macho nationalism (dushman ke ghar ghus ke vaar) after the Pulwama attack and the Balakot air strikes.

Then there are the weaknesses of the Congress; the local rivalries between CPM and Trinamool in West Bengal; the micro level caste arithmetic the BJP supposedly pulled off to win UP; the benefits that sections of the population derived from some government schemes and so on. All of these are valid factors that we should be alert to of course, but these would explain BJP becoming the single largest party without a majority; they do not necessarily explain the scale of the victory – the number of seats, the margins in each seat.

Especially as after the exit polls there was complete silence on the indubitable failures of the Modi regime – the all time low on employment front; destruction of the informal sector after demonetization; state owned banks drowning in bad debts to crony capitalists; agrarian distress, targeted attacks on Dalits, Adivasis and Muslims by Hindutva-based gangs, the overall climate of fear and uncertainty. None of these were invoked even to express surprise at the results, which were suddenly presented as inevitable. “Consolidation of Hindus” and “popularity of Modi” became the go-to answers for the conundrum of the scale of the sweep. In fact, the sweep is not even seen any longer as a conundrum requiring an explanation. But if religious community identity and caste identity are primary explanations for the BJP’s victory, then since these identities are not going to change, and Modi presumably has a long life ahead of him, election results are fixed for the foreseeable future.

But survey information is not self-evident – it has to be read and interpreted, there are corollaries to every feature of a survey. Take the Hindu-CSDS Lokniti post-poll survey, arguably the most credible one. It shows that support for BJP rose across all Hindu castes and communities, from 36 percent in 2014 to 44 percent in 2019. Adding the NDA allies, the support went from 43 percent to 52 percent of Hindus polled.

But if 48% of Hindus are not voting for BJP or its allies, then Hindutva did not succeed with the community as a whole; for instance, in Kerala where it is understood that on the back of Sabarimala, it was Congress that gained, not BJP, precisely because the vote was not a Hindutvavaadi vote. And on the other hand, we cannot assume that it was Hindutva that led to votes for NDA allies such as AIADMK, JD-U, Shiromani Akali Dal, Naga People’s Front, and Pattali Makkal Katchi.

Nor are all the votes even for BJP itself, necessarily pro-Hindutva, especially if we are taking seriously the “micro-management of caste” argument about BJP in UP, for that involved concrete material benefits of different kinds, both constitutional and extra constitutional. Take this report that says:

…unlike the west UP where there were attempts of a subtle communal polarisation through debates of ‘Ali vs Bajrangbali’ and a slight jingoistic appeal for Hindu nationalism through exaggerated claims about national security and Pakistan bashing, the campaign narrative has been more around caste appeal as the election moved towards east UP. It’s for this reason that Prime Minister Modi on multiple occasions reminded of his “most backward caste” credentials and also tried to converge caste dynamics through common agenda of poverty.

Also, in this kind of situation, when the non-Yadav OBCs and non-Jatav Dalits vote for BJP, it is not necessarily a vote for Hindutva, but against Yadav domination through SP and Jatav domination through BSP.

As for non-Hindus, the percentage of Muslims voting for BJP remained the same at 8 percent in 2014 and 2019, Christians voting for the BJP went up from 7 to 11 percent, and among Sikhs, declined from 16 to 11 percent. The distinctly lower percentage of non-Hindus voting for BJP is not surprising given its anti-minority stance, but evidently, other factors than Hindutva come into play locally, or else these figures cannot be explained.

So while we need to understand the role of Hindutva in the rise of support for BJP, treating it as the final definitive answer is effectively a closure of our minds to the ways in which the BJP as opposed to the RSS, has to function as a political party seeking votes.

Is there a ‘Level Playing Field’? BJP’s extra-constitutional advantages in elections

We cannot continue to discuss the elections as if all parties are functioning in more or less an equal manner with regard to resources – especially with regard to the use of official machinery. The situation has dramatically transformed in the last 5 years in particular. India is no longer the democracy, however flawed, that it has been till 2014. Let us recognize the disproportionate muscle power the BJP wields during elections in terms of funds, its control over the media and through the subversion of all constitutionally mandated institutions that it has achieved.

Funds

Prashant Bhushan notes that there are no limits on spending by political parties and no compulsion on parties to receive and spend money only through banking channels. These lacunae benefit the BJP the most, a clear indicator of the kinds of policies it promises and enacts.

According to the Association for Democratic Reforms, an elections think-tank, BJP received 73.5 percent of the combined declared income of the seven largest political parties in the financial year of 2017-18.

Bhushan points out in addition to the above, “three retrograde changes” in the law of election funding that have increased the role of money power and corporate hijacking of elections.

a) The Foreign Contribution Regulation Act brought primarily to prevent parties, candidates and public servants from getting and being influenced by foreign funds, has now been amended (2016) to allow receipt of foreign funds through subsidiaries of foreign companies.

b) The limits on corporate donations to parties and candidates which was earlier 7.5% of their profits has been removed to allow unlimited corporate funding (2017).

c) The introduction of electoral bonds in 2017, which are bearer bonds allowing anonymous funding of political parties even through banking channels. Bhushan points out that electoral bonds clears the way for payment of bribes by corporations to the ruling parties. The BJP, unsurprisingly, has received about 95% of the approximately 2000 crores of the funding through electoral bonds in the last 2 years since they have been introduced.

What this means is that the BJP has to pay back, not voters, but its funders, through policy measures. For instance, within five months of the Supreme Court judgement declaring Aadhar linking cannot be mandatory for bank accounts and mobile phone connections, the BJP cabinet promulgated an Ordinance to allow for “voluntary” use of Aadhar for both. An Ordinance was necessitated as the Bill, delayed by lack of sanction in the Rajya Sabha, would have lapsed with the previous Lok Sabha. Hence the Ordinance was hastily passed one month before the Lok Sabha elections – so urgent was the need to pacify the corporates!

Or, take the permission given to Adani in March 2019 to conduct open cast mining in Hasdeo Arand in Chhatisgarh, one of the largest contiguous stretches of very dense forest in central India.

There is a reason why the BJP’s pockets are very, very deep and dark.

Control over media

What has been described by some commentators as Modi’s masterful “control over the narrative” is in fact near total control over the media – through ownership by direct BJP supporters or by those with vast business interests who want to please the government for quid pro quo’s, or who at the very least, don’t want to rub the government the wrong way; or through fear and intimidation and blackmail, or monetary benefits. Some editors who generally stand up to this pressure are still forced from time to time to toe the line.

For instance, on the very day of the 7th and final phase of polling, the otherwise usually balanced Indian Express published a front page interview with the Prime Minister, who is not exactly known for placing himself for scrutiny before the media. In this interview that ran over three pages, Modi added “Khan Market gang” to the other gangs that roam India-that-is-Wasseypur – the tukde tukde and the Lutyens, at last count.

Or take the India Today story that lists 5 reasons that got Narendra Modi another term. These “reasons” are simply BJP claims, listed baldly as claims – the Modi government claims to have built so many toilets, it claims to have distributed so many gas cylinders; it claimed Balakot as a victory of its strong muscular policy towards Pakistan, and so on. In other words, BJP’s press handouts and/or confidential chats with journalists are being treated as facts. Of course, one is grateful for the overwhelming number of times the word ‘claim’ is used in this story. Many others simply report such claims as facts.

Nikhil Inamdar has discussed at length the death of Indian media at the hands of the Modi regime, including through arm-twisting non-compliant media proprietors.

Raiding news channels, boycotting prime-time debates, and stopping government advertising—a significant source of revenue for the industry—have been among the common tactics used by the Modi regime.

The use of social media to target critics and mobilize public opinion, and well funded and organized trolling are part of the BJP’s arsenal. The BJP has also been openly selective in handing out TV licences to new applicants, controlling who enters the fray. Unwillingness to toe the line has often led to high-profile editorial sackings.

In May 2018, a sting operation by an outfit called Cobrapost showed that some 25 of India’s leading media organisations, including giants like The Times of India, The New Indian Express, and the India Today Group were willing to participate in propaganda for the BJP. Other outlets recorded in the sting, even agreed to spread communal hate in return for cash from the ruling party.

The sting was in some sense reflective of the extent to which the institutional nexus between mainstream media and the government had strengthened under this regime and possibly a harbinger of what was to come post-Pulwama.

Inamdar is referring to the way in which after Balakot air strikes,

India’s television stations dispensed with even basic journalistic rules, as seasoned reporters declared unequivocal allegiances and experienced editors parroted exaggerated claims. Theatrics abounded, with toy-gun toting warrior anchors in army fatigues drumming up an atmosphere of hate and violent jingoism.

In short, media narratives except for a few well known exceptions, are practically crafted by the BJP PR department.

Judiciary

Prashant Bhushan discusses in detail the way in which every institution has been subverted by the BJP – the CAG, the CBI, the Central Vigilance Commission and the Lokpal.

But in the context of elections, the institution that matters the most after the Election Commission, is the judiciary, upon whose independence there has been a determined assault by this government. The attempt to bring back the executive into the role of selecting judges through the Judicial Appointments Commission was scuttled by the Supreme Court, but this government has still attempted to block appointments of judges recommended by the collegium, by just “sitting on those names that it finds inconvenient”. It has also refused to appoint inconvenient judges whose appointments have been reiterated repeatedly by the SC collegium.

The proverbial “clean chit” issued to Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi by the “in-house” committee of the Supreme Court set up to enquire into a charge of sexual harassment against him, and the spirited defence of him by Union Minister Arun Jaitley, does not augur well for the independence of the highest court in the land. Especially as immediately after the CJI was cleared of all charges, a Supreme Court bench headed by himself issued notice to advocates Indira Jaising, Anand Grover and their NGO Lawyers’ Collective on a PIL seeking court-monitored SIT probe into an alleged Foreign Contribution Regulation Act violations. It may be noted that Jaising claims she is being victimized for having spoken up against the illegalities in the enquiry against Justice Gogoi.

This stranglehold that the Sangh backed Modi regime has over multiple institutions in the Indian polity cannot merely be remarked upon, as if once noted, it can be business as usual for Indian democracy.

These factors have to be recognized as decisively shaping BJP’s electoral victory, for this is the kind of control over and subversion of all institutions that the BJP has been able to establish.

And now, to the conduct of the 2019 elections.

Election Commission, EVMs, ‘ghost voters’ and much else

Let me make it clear that we can only raise questions based on the scattered information available to us. It is not our job as citizens to offer proof of wrong-doing of the highest institutions in the land, when these institutions function in so opaque a manner. It is our job to raise questions about visible anomalies. It is the responsibility of the Election Commission to explain the anomalies. This is also the responsibility of the government, but I have no expectation that this government, riding high and arrogant on the back of its “massive mandate”, will take heed of the voices raising questions, except perhaps to discipline us in various ways, or charge us with sedition.

There are four questions here that need to be addressed.

- Internal functioning of the EC and bias it has shown

- Whether EVM’s are immune to hacking as claimed

- What is the explanation behind the missing EVMs as revealed by an RTI. This is linked to the question of “tally mismatches” or “ghost voters”.

- The mass deletion of voters’ names

1. Biased EC.

The EC issued “clean chits” to Modi and Shah in cases of multiple blatant violations of Model Code of Conduct, which was challenged by Election Commissioner Ashok Lavasa. He was not only overruled but it was decided that dissent notes would not be recorded. Lavasa then recused himself from meetings of the EC. The complaints on MCC violation included the Prime Minister saying in a speech that his government kept Pakistan on its toes to secure the safe release of IAF Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, and his appeal to first-time voters in Latur to dedicate their first vote to “the Pulwama martyrs”. Lavasa had also wanted the EC to issue a show-cause notice to Rahul Gandhi over his “chowkidar chor hai” slogan but in the meanwhile a BJP Minister took it to the Supreme Court as a matter of contempt, which was admitted and heard by the court, leading to an apology by Rahul Gandhi, so the EC did not need to act on it. The EC also ignored the continued operation of Namo TV and refused to recognize the open and blatant use of religious and anti-Muslim rhetoric in the campaign by the ruling party.

The internal functioning of the EC evidently is far from democratic. Majority decisions are being pushed through, and minority opinion buried. These majority decisions were largely to the benefit of the government.

Openly biased EC. Check.

2. Are EVMs immune to hacking.

The Election Commission says no, Indian EVMs cannot be hacked. So all the arguments about EVMs being given up the world over, due to their susceptibility to hacking, are irrelevant to India. The reason the EC gave in support of their confidence was that the micro-chips used in Indian EVMs are One Time Programmable (OTP). So they cannot be tampered with. Nevertheless, despite this confidence, they refused to permit a public examination of EVMs, and when put under pressure, in 2017 agreed only to a four hour test which most parties boycotted.

There are three points we need to take up.

a) It transpires that the EC did not provide correct information when it claimed that the microchip used in Indian EVMs is One Time Programmable (OTP).

Two public sector companies manufacture EVMs – BEL and ECIL. The microchips for all Indian EVMs are however manufactured by companies in USA and Japan. According to Rajat Moona, Member, Technical Expert Panel on EVMs, EC, blank chips are imported by BEL and ECIL, then the source code is developed and programmed by them and coded on to the EVM chip.

Venkatesh Nayak obtained information through RTI in May 2019, which revealed that :

The micro-controllers (computer chip) embedded in the BEL-manufactured EVMs and VVPATs used in the current elections, are manufactured by NXP – a reputable multi-billion dollar corporation based in the USA.

While the ECI continues to claim that the micro-controller used in the EVMs is one-time programmable (OTP), the description of the micro-controller’s features on NXP’s website indicates that it has three kinds of memory – SRAM, FLASH and EEPROM (or E2PROM). A computer chip which includes FLASH memory cannot be called OTP.

Read Nayak’s detailed piece on his RTI enquiry and the answers he received here. He could not get information on which companies manufacture chips for ECIL, which was refused on grounds of confidentiality.

If the chips are not OTP, it means they can be reprogrammed.

b) Secondly, add to this the information that there appears to be a connection between one of the US based companies that manufactures microchips for Indian EVMs and the company that benefited from the Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation (GSPC) scam while Modi was Chief Minister of Gujarat. According to the CAG report, Geo-Global Resources, a private company listed in Barbados and based in Ahmedabad, was taken as the private exploratory partner without any transparent bidding, and also offered 10% stake in GSPC. The start-up company was preferred over ONGC. The CAG report found that the exploration activities undertaken by the GSPC along with Geo-Global Resurces led to a government loss of over Rs 20,000 crore and did not result in any fruitful oil production.

Janta ka Reporter states that (i) Geo Global Resources Inc is a subsidiary of Key Capital Corp, a financial group in USA, and (ii) the ownership pattern of Key Corp and Microchip Inc, USA that manufactures microchips for the EVMs used in India is strikingly similar.

Is there then, a connection between a company that was unduly favoured by Gujarat government under Modi, and one of the companies that manufactures EVM micro-chips for India?

The EC in its FAQ, published by the government’s publicity department, PIB, says, ” The Software Programme Code is written in-house, by these two companies (BEL and ECIL) , not outsourced, and subjected to security procedures at factory level to maintain the highest levels of integrity. The programme is converted into machine code and only then given to the chip manufacturer abroad”.

The doubt raised by Janta ka Reporter is that since the microchip manufacturing companies in the US and Japan deliver microchips in a sealed condition, for security, even the EC is not in a position to verify if its original programme code, prepared by its scientists at BEL and ECIL has been modified.

c) Third, VVPATs, the paper audit trails that act as independent verification for EVMs:

(i) why was the EC so resistant to VVPATs for the 2019 elections conceding only when forced to by a Supreme Court order?

(ii) Why did the Modi government try and pressurize the EC to buy VVPATs from private sources?

The Law Ministry sent three letters, between July and September 2016, seeking EC’s views on the suggestion, as Indian Express learnt through an RTI. The Express story adds:

Documents show this suggestion had its origins in a meeting held in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) on July 11, 2016.

Nasim Zaidi, the Chief Election Commissioner at the time, firmly turned down the suggestion as it could hurt the credibility of the election process.

(iii) Why did EC resist even 50 percent verification of VVPAT after the polls, before declaring results, accepting only 5 booths per Assembly constituency?

The reason EC gave for not accepting 50 percent verification, was the laughable one of “delay in the declaring of results”. Surely a delay in declaring results (after such a long drawn out election process) is preferable to accepting the possibility of “malfunctioning” on a large scale?

Rajendran Narayanan and Nikhil De make the irrefutable ethical point that statistical sampling is simply not sufficient to check “malfunction” in the case of elections, where every single person’s vote is meant to count:

There are approximately 10.35 lakh EVMs used in this election and so even according to this model, the way the EC is conducting the so called “audit” runs the risk of many undetected errors. Correct counting of votes cannot be left to chance and so statistical estimation and random sampling in the context of counting of votes should not even be an option. The right to a secret verified ballot is the most fundamental right of a citizen, and the verified slip, and not the opaque EVM machine should be counted as that ballot, otherwise it is akin to the state surreptitiously stealing the most fundamental right of a citizen. Counting anything less than 100% of the VVPATs must ideally be deemed unconstitutional.

**************************************************************

In the light of all this information in the three points above, the innumerable stories from 2014 onwards, of “malfunctioning” EVMs (and all of them malfunctioned in the same way – by lighting up for lotus whatever the button pushed) need to be revisited.

I actually cannot list them all here, a quick search reveals far too many cases reported in the media. And often, it is not a single EVM, it’s several. In Karnataka Assembly elections, it was 2400! In Kairana Lok Sabha and Noorpur Assembly by-polls in 2018, the EC dismissed claims of “malfunctioning” EVMs, claiming they were “briefly affected” by the heat.

And remember, this is not an exhaustive list of even the instances reported in the media, it is merely the tip of the iceberg.

Some complaints were “found to be false”, others proved correct and repolls ordered.

In one case at least, that we know of, the claim of malfunctioning EVM was “proved false” by asking other voters present, not by checking the machine itself. In Muzaffarnagar, a BSP worker Dara Singh, was booked for “spreading rumours”, and the SDM told the Indian Express:

Singh told us that he has been informed by two-three voters that on pressing any button of their choice, the vote was going to BJP’s symbol. We cross-checked the information with other persons who had cast their votes and the allegations turned out to be false. Since we got confirmed information that Singh made false allegations, we did not check the EVM machine. Today, I filed a complaint with the police to lodge an FIR into the matter.

A “malfunctioning” EVM need not malfunction every single time, nor would voters who pressed the lotus have experienced any malfunction. So “asking other voters present” is at best a lackadaisical, and at worst a motivated, way of looking into such a serious complaint.

The fear of arrest as provided for in the law, if a claim is “not proven”, stopped even a former top police official from lodging a formal complaint:

Former Assam DGP Harekrishna Deka has alleged that the voter-verifiable paper audit trail (VVPAT) machine at a polling booth in Guwahati had malfunctioned as the machine displayed some other name and not the one he had voted for. Mr Deka, however, said he did not lodge a formal complaint fearing punishment if the claim is not proved.

“I don’t want to take the risk,” he said adding, “How do I know how will it be proven?”

And as has been pointed out innumerable times in the course of this debate since 2014, it is not necessary to tamper with every single EVM to win an election, it is possible to do so strategically, using information that most parties, and especially the BJP, have about specific booths and constituencies.

The Caravan carried a story that in March this year, the Election Commission filed an affidavit before the Supreme Court that “made blatantly false claims”. The affidavit claims that there had not been any mismatch in the VVPAT and EVM tallies conducted in the past two years, and that the EC had only received one complaint about a VVPAT recording an incorrect vote since 2013. However, the story goes on to establish the large number of such complaints that have in fact been recorded.

Rigging through switching Ballot Unit and Control Unit numbers

At local level polls, less technologically advanced stratagems have been adopted to rig EVMs. For instance, in February 2017 in Pune, in which BJP swept the civic polls, RTI activist Vijay Kumbhar explained that:

As per procedure, the EVMs were checked, randomised, allotted booth and sequence wise, and sealed in presence of the authorities, candidates or their representatives, and a representative of the EVM manufacturing company on February 15, six days before the voting. The randomisation implies allotment of Ballot Unit (BU) and Control Unit (CU) numbers to corresponding booths, with the BU and CU charts given to the candidates or their representatives. The sequence of candidates was also set on the same day.

“However, on the actual polling day [February 21], when the polling staff opened ballot units, the serial numbers were different from those recorded and sealed on February 15,” said Mr. Kumbhar.

The rules plainly stipulate that a ballot unit be connected to the control unit according to a particular sequence allotted to them.

“Changing that sequence is tantamount to an exchange of votes among candidates. Just how anyone could have access to sealed machines is anybody’s guess…” said Mr. Kumbhar.

I might add that the first doubts about EVMs were raised by the BJP after Congress won in 2009. The Huffington Post story linked to above is written in that context. That the doubt was raised first about Congress does not in any way reduce the validity of the questions we raise. Any party is capable of trying to rig an election. It is we citizens who must be vigilant.

“Malfunctioning” (rigged?) EVMs. Check.

3. ‘Missing’ EVMs.

This mystery is related to two other serious issues during the 2019 elections –

- the as yet unaccounted for movement of EVMs in private vehicles in different parts of the country , which the EC has not satisfactorily explained; and

- the mismatch between the ECI figures for voter turnout and EVM votes cast.

These are in fact, pending issues from 2014. In Banaras, the site of the Kejriwal-Modi contest, for example, where Kejriwal lost by over 3 lakh votes, there were reports of EVMs turning up in odd places. For instance, a Sector Magistrate took some machines home and his son took photographs of the EVMs in his bedroom, and posted them on Facebook. We have no idea of what the follow up to this was, nor about the scale of the tampering during the 2014 elections.

A case was being heard in the Uttarakhand High Court in 2018, regarding EVM tampering in at least 6 constituencies in the Assembly elections of 2017, which I have been able to track till April 2018, when the next date for a hearing was set as May 4, 2018. All the while, of course, the BJP government continues its regime.

At one point, the Uttarakhand High Court even issued a gag order on criticism of EVMs. Because of course, that is the problem – drawing attention to anomalies in the election process.

Let us come now to 2019.

(i) The missing and fugitive EVMs.

A series of RTI applications by Manoranjan Roy regarding the number of EVMs produced by BEL and ECIL and the numbers received by the EC, revealed major discrepancies (19 lakh ‘missing’ EVMs) and he then filed a PIL in the Bombay High Court, hearings on which have been going on for about 13 months now.

Venkitesh Ramakrishnan in a carefully documented story in Frontline outlines the “glaring discrepancies” highlighted by the RTI documents procured by Roy

…in all three operations—procurement, storage and deployment—and also pointed to grave financial irregularities to the tune of Rs.116.55 crore. The documents, submitted as “exhibits” to substantiate the arguments of the PIL, brought out huge disparities between the accounting of the number of EVMs the ECI had received over a period of time and the supply records of the manufacturers. They show that nearly 20 lakh EVMs that the manufacturers affirm to have delivered to the ECI are apparently not in the latter’s possession. Neither the ECI nor the SECs have been able to throw light on the issue of the missing EVMs despite seven hearings of the PIL over the past one year.

Roy’s petition also raised grave doubts about the movement of EVMs from one State to another without proper records such as their number, serial number, model number and mode of transportation. It pointed out that the absence of proper systems and infrastructure too could lead to misplacement of EVMs along with misappropriation of funds. Even on the question of destroying old EVMs, there is no clarity, it stated.

Further, it has emerged that no audits have been conducted by the State Election Commissions of Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh on EVMs.

On April 5, 2019, the court directed the ECI to file its replies to Roy’s queries on or before the next hearing on April 23, 2019. In a characteristic delaying mode, no reply was filed before that date. The court stayed proceedings on the petition for two weeks, and the next hearing has been scheduled for July 17.

The EC sent a response to Frontline, to which Ramakrishnan responded. The two main points in his response are:

- ECI says Frontline has “selectively quoted some information obtained by an individual through RTI applications from multiple public authorities and a PIL filed in the Bombay High Court”. The obvious mismatch between the data given by “multiple public authorities” is precisely the problem. “On a matter as crucial to the democratic process as EVMs, the public expectation is that the ‘multiple authorities’ would come up with exactly the same number.” But the ECI response makes no effort to explain the mismatch, which, if it occurred due to clerical errors in any of the institutions, would have been mentioned in the response.

- The ECI response asserts that “the commission has a robust EVM management software (EMS ) through which the status of every EVM/VVPAT can be tracked on real time basis and only first level check cleared EVMs , properly logged in EMS are used for poll- purpose”. Despite such claims, Ramakrishnan points out, there have been regular media reports about the discovery of EVMs in places such as hotel rooms, which the EC has not explained.

We know that the EC’s response to all such reports – see also here – showing unsupervised transportation of EVMs is that they were spare EVMs, but why was there such a large volume of movement of spare EVMs just before counting, in such an informal, unsupervised manner?

Further, The Quint reports that

The Election Commission of India (ECI) had mandated real-time GPS tracking of all vehicles transporting Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs). However, a day before the election results were declared, the Commission in response to an RTI query, said it has no information in “any material form” related to the GPS data and movement of these vehicles.

In its response to Roy’s petition, the ECI also declared that it had no information about the possibility of any EVMs being delivered to the State Election Commissions (that conduct local body elections), as these are autonomous of the ECI. Does this mean there are no centralized figures available as to how many EVMs reach the ECI and how many the SECs? This is a very casual way of accounting for so critical a commodity to the functioning of a democracy!

But if SECs are completely autonomous to the extent that the ECI does not even know how many EVMs are delivered to them, how to understand the inexplicable and controversial directive by the Election Commission of India in May 2017, restricting BEL and ECIL from selling EVMs to State Election Commissions? The matter was discussed during the all India conference of State Election Commissioners, held in November 2017 and a copy of the minutes of the meeting was received in reply to RTI query, which revealed that the State Election Commissioners objected to this directive, as “Different designs of EVMs for use by the ECI and SECs, will further create confusion both among the voters and the political parties about the use and credibility of the machines.”

If the SECs are autonomous of the ECI, then how could ECI take decisions regarding supply of EVMs by BEL and ECIL (also autonomous of the ECI) to SECs? And what was the intention?

(ii) Mismatch between figures of voter turnout numbers and EVM votes cast.

Two detailed and exhaustive stories in NewsClick and The Quint pointed out significant discrepancies in these numbers available on the ECI site, with votes recorded as counted, being in excess of votes recorded as cast. The Quint found serious discrepancies in the two sets of data in 373 constituencies which went to polls in the first four phases of the election, while Newsclick found similar mismatches in several Lok Sabha constitutencies , including including three high-profile ones – Patna Sahib, Jehanabad and Begusarai.

In response, after several days of silence, (and after taking down the votes polled data from its site after receiving questions from The Quint), the ECI said in a rambling statement on June 1, 2019, that the figures were “provisional”. Please remember that the far-from-provisional government had already been sworn in the day before. Well over a week after declaration of results, and after the government has been sworn in, the figures were “provisional”?

The Quint spoke to former chief election commissioner OP Rawat about the discrepancies. He said:

Prima facie, it appears to be a serious issue. I am not aware of any such occurrence (where votes polled didn’t match with votes counted) in the past, that is, during my tenure as chief election commissioner.”

Please note that in Rawat’s tenure as CEC, in 2018, there were by-elections to the Lok Sabha, elections to the Rajya Sabha, elections to legislative assemblies of eight states and numerous other by-elections to state legislative assemblies and councils.

Three former CECs to whom NewsClick spoke also said they were surprised at these discrepancies. H.S. Brahma who headed the Election Commission in 2015, told Newsclick that discrepancy of up to, say, a couple of thousand votes could be understood because sometimes there are issues with postal votes. “But anything more than that needs to be investigated and explained,” he added.

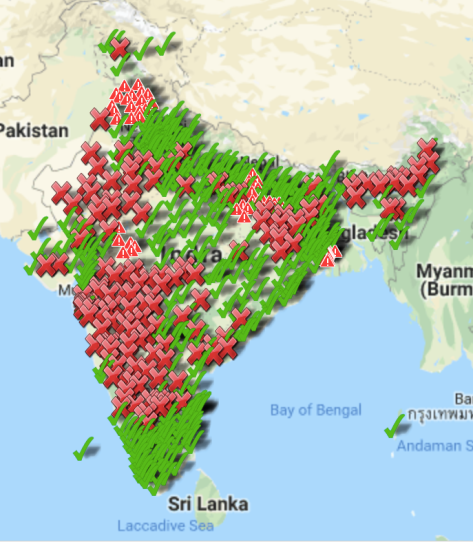

Here is a comparison of constituency-level “votes polled” & “votes counted” data prepared by Vidyut on aamjanta.com, for each Constituency in which elections were held during the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections.

It contains constituency level voter turnout data only for the first 6 phases because only this data is available on the ECI site.

For the seventh phase, there is only state level data on turnout… Yes, that is correct. The Phase of election in which India’s Prime Minister as well as several other cabinet ministers were elected to Parliament does not have ANY constituency-level turnout data available. Not before counting, not before government formation, not even after government formation.

The green ticks indicate that there is a possibility that the data is accurate (if the mismatch in total is caused by another constituency and not the one with the tick), while the red crosses indicate that the EVM votes counted do not currently match ANY voter turnout data provided.

Meanwhile, the “final turnout” data has been deleted by the ECI and replaced with provisional data.

What are we to make of this saga of statistical manipulations?

Are the missing EVMs somehow coming into play here?

Some at least of my generation must feel we are living inside the Costa Gavras film Z, a thriller about deep levels of conspiracy and massive corruption in the political establishment, in which idealistic citizenry take on a fascist regime…

Statistical chicanery by the ECI. Check.

4. Large scale deletion of voter names

During 2014 elections in Banaras, the opposite was the case. the Navbharat Times reported that 3,11,057 fake voters had been discovered in Varanasi, where Modi had won by a margin of 3,71,784 votes.

The ECI claimed that the person who wrote the story had “understood it in a wrong perspective”. There were not 3 lakh bogus voters, but 6.47 lakhs repeated names, an official claimed. The ECI’s explanation was that these are not all necessarily fake entries in the rolls. They could be people who share a name. “For instance, a ‘Rajesh, son of Ramesh’, might be found several times in UP,” an official said. “We are in the process of checking whether these people are same or different.”

The question is, when the process was to compare both the voter’s as well as his/her father’s name with other voters, how were 6.5 lakh duplicate names found in a constituency with 17 lakh voters? And why was this exercise being carried out after the crucial Lok Sabha elections?

In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, a survey found that in Uttarakhand, 12-13 per cent of the total electorate was disenfranchised by their names being removed from the voter list, of which 90 per cent are Dalit and Muslim voters.

In Delhi, the names of many long-time residents, including a retired government employee, were found missing in the voters’ list.

In Karnataka, too, there were reports of large numbers of long-time voters not finding their names on the list and so being unable to vote. More than 5 lakh voters were deleted from the Bengaluru electoral rolls between May 2018 and January 2019, while only around 4 lakh new voter names were added.

Similar complaints of missing names came from UP; from Mangaluru; from Tamil Nadu (where it was claimed that Muslim and Dalit names had been deleted); and missing names and bogus voting were reported from Mumbai.

Manipulation of voter lists. Check.

Conclusion

Let me reiterate. India is not the democracy, however flawed, that it was up to 2014. There have been deep tectonic shifts in the functioning of the state. Has the functioning of a robust democracy protected by its institutions and a Constitution, for over 70 years, weakened our capacity to fully assimilate the extent to which all these have been subverted in so short a time? For instance many well- intentioned people with no love lost for the BJP, still defend EVMs with all their hearts – their belief in technology as neutral, their belief in statements and claims made by the ECI, their resistance to a “conspiracy theory of history”.

True, all of history cannot be explained by conspiracies. But this does not mean there are no conspiracies in history!

There has been rigging and booth capturing before. But make no mistake, this is of a different order altogether.

As alert citizens we need to take stock seriously now. We need to remember that the first and last time the election of a Prime Minister of India was set aside (by a High Court Chief Justice) in 1975, was for misuse of government machinery for election campaigning; for violation of the Model Code of Conduct, in short. How laughable those grounds seem now.

Now, in 2019, when an IAS officer on poll duty in Odisha checked the Prime Minister’s helicopter, he was suspended; and a large black box that was whisked out of a helicopter in which the Prime Minister arrived in Karnataka and put into a private car, remains unexplained. Remember also that the Prime Minister has sworn on affidavit to educational qualifications that till today remain unverified because of the resistance put up by Delhi University authorities,

During these elections of 2019, we have seen the complete collapse of the EC under pressure from the government; the strong possibility of EVM manipulation and replacement of EVMs; the consistently higher number of votes cast over number of voter turnout; mass, often selective, deletion of voter names; legal changes to permit huge amounts of unaccounted money to pour into one party’s coffers…

Immediately after the 1975 judgement by Justice Sinha (who withstood all pressure to deliver it), Indira Gandhi declared Emergency. The rest as they say, is history. Emergency was resisted across India with great courage and personal sacrifices, and India Gandhi defeated in the elections that followed.

What will the future say about this moment of the “massive mandate”?

Large numbers of active citizens are speaking up, more and more of them, thanks to social media and a few media outlets that remain independent. How should we act upon all the information that is emerging?

There is no doubt we are at a perilous watershed in the history of our democracy. I think we all know this.

First published on https://kafila.online/