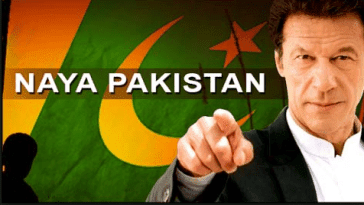

Imran Khan’s government came with the promise of establishing a new Pakistan. There were huge expectations when he tried to steer clear from the trappings of royalty like deciding not to stay in the official residence of the prime minister. But then, recent happenings, especially the controversy around the economist Atif Mian, perhaps is a reminder that the slogan of Naya Pakistan was just an empty rhetoric aimed at deflecting attention from the deepest structural defects that this country faces.

Atif Mian is a celebrated economist who teaches at Princeton. His inclusion within the Economic Affairs Council (EAC) should have been looked at from a purely professional point of view. But then, in Pakistan, increasingly, everything has to pass through an Islamic lens whose focus is getting narrower with each passing day. All hell broke loose when it was discovered that he was an Ahmadi which the Pakistanis for some curious reason consider non-Muslim.

Everyone forgot his brilliance as an economist and what he could have done for turning around the country’s sagging economic prospects. All that people in Pakistan could see was his religious identity. True, the government initially supported him, but then faced with the onslaught of the Mullahs, it had to backtrack. Atif Mian resigned in disgust or perhaps was asked to leave by the government. The flag of Naya Pakistan wilted under the intense heat of Islamic bigotry, some of the bigots being close allies of the ruling party.

It was not so long so long ago that Imran Khan’s PTI was in an informal alliance with the leading Barelwi organization, Tahreek e Labaik. A fanatical Barelwi platform, it cut its teeth advocating for more stringent blasphemy laws in Pakistan. Moreover, like many Islamist political formations, Tahreek e Labaik, wants an Islamic sharia driven state in Pakistan. The PTI thought that by aligning with such a party, it will be able to reach the religious voters and indeed this is what happened. But then, such an alliance partner, which has fascistic tendencies also knows how to extract is pound of flesh. It was very naïve of Imran Khan to think that after forming the government, he would simply forget about his former alliance partner and go about building a new Pakistan.

The appointment of Atif Mian, an Ahmadi, gave the Barelwis a new handle to remind the government of their presence. But then, this is not just about the Barelwis. Rather, this is about how Pakistan has conceptualised itself as a nation, and who it has defined itself against. In many ways, this incident is a reminder that there is problem with the idea of Pakistan itself and till the time this nation does not start confronting those fundamental questions, there is going to be no ideological foundation for Naya Pakistan.

For a country founded as the new Medina, Islam became a master signifier for all practical purposes. No longer was the Hindu a threat; therefore a new enemy had to be imagined. Had the new nation been formed on the basis of secular and democratic principles, there would have been no need for such an internal or external enemy. But then the Islamic nation of Pakistan need an internal threat and the Ahmadis came handy. Jinnah, the architect of Pakistan, wanted Muslims to forget about their identities in new Pakistan. But this was better said than done.

For a person who made career out of hatred against the Hindus, it was rather rich for him to say that Muslims of Pakistan should cease to have an Islamic identity. Soon after his death, his law minister, Jogendra Nath Mandal, foresaw what was to become of Pakistan and decided to leave the country for good. Had the ruling establishment of Pakistan been sensitive to the pain of Jogendra Nath Mandal, perhaps things would not have come to such a pass.

But then, the roots of Pakistan’s Islamic intolerance go much further into the past. And the national poet of Pakistan, Muhammad Iqbal, contributed to this bigotry in no small measure. After all, he was the one who publically praised the killer of the alleged blasphemer, the publisher of Rangeela Rasul. In one of his poems, he said that his whole intellectual production was worthless in front of the bravery of the killer Ilm-Uddin, who murdered the publisher Rajpal. It is perhaps not astonishing that Iqbal is revered as someone who first dreamt the idea of Pakistan. How does one then blame the thousands who decades later marched in favour of the killer of Salman Taseer? After all, the killer of Salman Taseer had only done what the founders of Pakistan had called as a divine act. How do you then condemn the Tahreek e Labaik when it demands the resignation of minsters or when it wants the Sharia to be proclaimed as the state law of Pakistan?

It is ironical that groups of Islamic parties in Pakistan are executing the power of church when there is no church in Islam. There is no one way to be a Muslim. The Munir committee, which was constituted in Pakistan in the wake of anti-Ahmadia riots, reiterated this very aptly: the only way in which a Muslim can be defined is negatively, i.e. by excluding who was not a Muslim. In short, the committee came to the conclusion that there was no single definition of being a Muslim.

The implications of this were huge: anyone who called himself a Muslim should be able to do so without any fear or retribution. Remarkably, this understanding of being a Muslim is closer to the sociological reality of diverse lives that Muslims lead throughout the world. But then we really do not know what happened to that report. Today what Pakistan needs most is the sanity with which the report talked about Muslim identity.

Today, it is an Ahmadi; tomorrow it could a Shia. Yet another day it can be the Sufis. There is a problem at the ideological foundation of Pakistan itself. The country will continue to create enemies out of its own people, till the time it actively confronts its past. Pakistan today needs to dialogue with the ghosts of Jinnah and Iqbal and perhaps tell them unequivocally that they were wrong in ways in which they conceptualised Islam as the ideological bedrock of the state of Pakistan.

Arshad Alam is a columnist with NewAgeIslam.com

Courtesy: NewAgeIslam.com