Uttarakhand’s Gunji village is home to 194 families who still relieve themselves behind hedges in the biting cold of the mountains – and yet, the Swachh Bharat Mission claims the region is free of open defecation

They smile and greet each other, and branch off in different directions on various farmlands, many of them barren because their owners have migrated. And at that pre-dawn hour, a few of the early risers are already returning home with empty bottles.

The best places are behind dense and high hedges. At 3,200 metres, these are sparse and scattered. The early risers get these prized spots. And before the snow-covered Api mountain range turns orange and daylight arrives, it is time for Gunji’s residents to go down on their haunches.

Nearby, the Kuti-Yankti river is roaring, and horses’ bells rhyme with the hard sounds of their footfalls on the stony ground. Their owners or handlers are taking the animals to Garbadhar, 50 kilometres away, an area where they will wait to carry export items for the India-China border trade – the border is just 22 kilometres away.

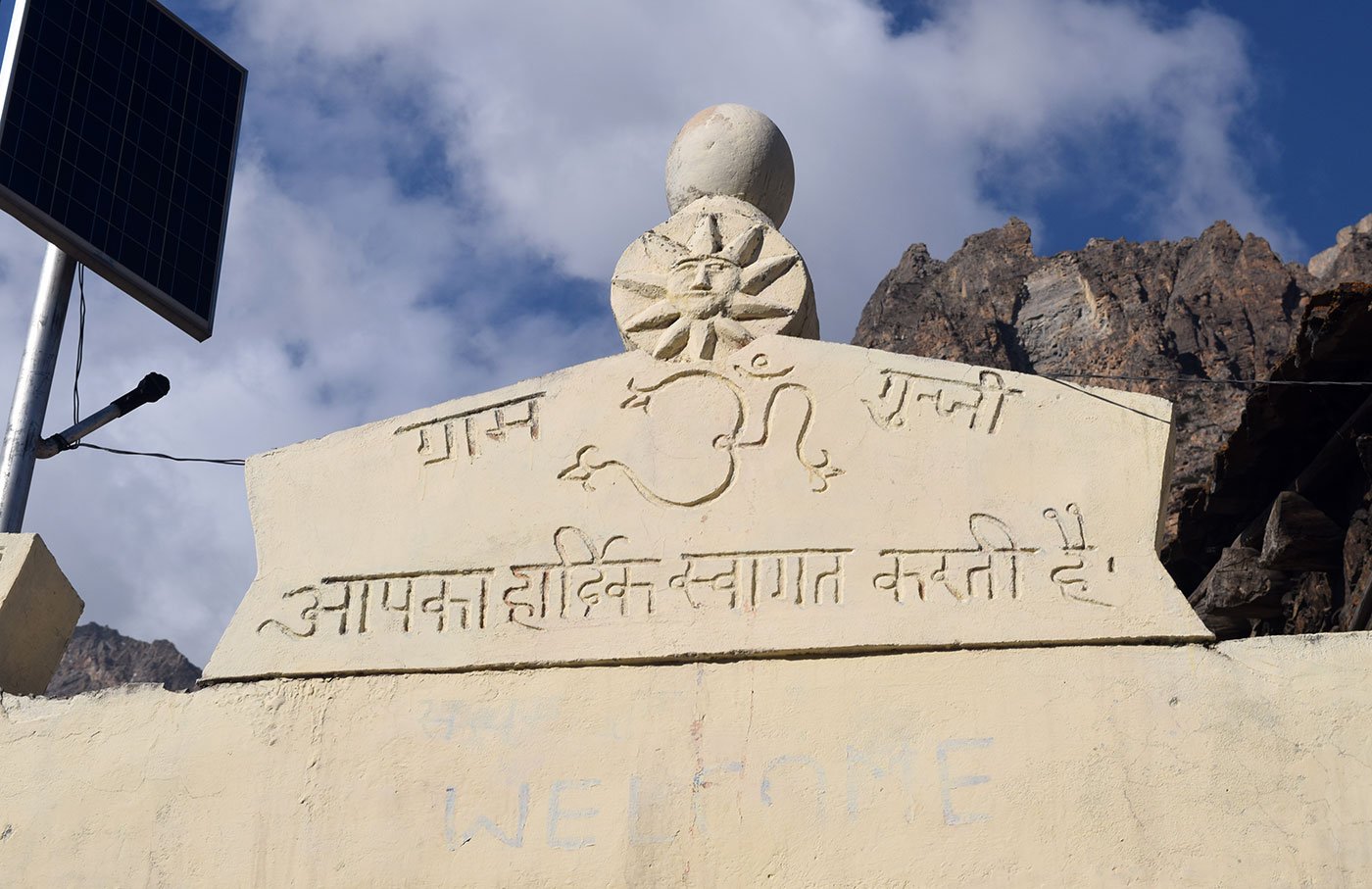

Gunji is one of the 21 upper-Himalayan villages of Dharchula block of Pithoragarh district in Uttarakhand. The people here are seasonal migrants. In November every year, families with their animals move down to their winter homes in Dharchula.

In early May, as the snow retreats, the families walk back to Gunji, a steep climb of 60-70 kilometres, over four days, and begin their farming season. When there is good rain (it’s been scarce or absent for two years) they harvest buckwheat, rajma, peas and other crops in October, and then return to their winter homes with their animals.

It’s not as if Gunji is an obscure place – it is one of the largest villages on the India-China border. It has an Indo Tibetan Border Police camp, a Sashastra Seema Bal camp, a customs office, and temporary branches of the State Bank of India and post office that remain open for only six months of the year.

But in the entire village of 194 families (Census 2011), there is only a single working toilet, that too of an Intelligence Bureau (IB) office. The IB is there because of the proximity to the international border, the potential for illegal trade and because pilgrims on the Kailash Mansarovar yatra pass through Gunji. However, even the IB’s toilet does not have piped water supply; a bucket of water has to be fetched from the tap every time the loo is used.

The village has only one tap, connected to the Kuti-Yankti river flowing nearby. People here use this water for drinking, bathing and washing clothes. During winter, when Gunji and its surrounding mountains are covered in snow, the water in the pipes freezes. Then the General Reserve Engineer Force (GREF) posted at Manila, 1.5 kilometres away, occasionally provides drinking water to the residents of Gunji.

Even the Intelligence Bureau’s toilet in Gunji does not have piped water supply; a bucket of water has to be fetched every time the loo is used

The records of the SBM at the block office of Dharchula show that every family of Gunji has access to toilets in their winter homes in Dharchula, located on the bank of the river Kali. But villagers say they continue to defecate in the open even in their winter homes due to the lack of water.

“We have no toilet here because we don’t have any water. In summer we get water from the piped connection, but then everybody comes to Gunji from Dharchula, so you get very little water for every person,” says Phal Singh Gunjiwal, who too stays on in Gunji during the winter months.

But how are toilets being built without providing water? And why are newly- built toilets locked? Archana Gunjiwal, the gram pradhan of Gunji, gives a peculiar reason: “These are new toilets. Without water, the villagers would make them dirty.” So when will they be linked to piped water supply? “It will take time. We have to develop more piped water connections; till that happens we can’t use these toilets,” she says.

In some instances, it is the people of the village who are resisting the change. “This is the way our ancestors and we have been living for ages. How can we stop living like this and change suddenly when an outsider is asking us to do so?” asks Sukhmati Devi, an elderly farmer in Kuti.

Courtesy:ruralindia.online.org