Though the government has begun the process of releasing the money to the banks, it might still take much longer for the money to reach farmers.

Govind Kapse, 30, shows the soyabean stored on their farm in Pimpalgaon Dhage village, Nanded district, gathered from this kharif season. Most of it was parched for rain due to the long dry spell in the region after the first showers. Kapse’s younger brother, Tukaram, committed suicide on October 23, 2017–five days after he had found that he was not to benefit from Maharashtra’s loan waiver scheme. He had a debt of over Rs 350,000.

Nanded (Maharashtra): Tukaram Kapse was only 10 when his father, Madhav, passed away. The oldest of six siblings, Tukaram took on most responsibilities at home and on the family farm in Pimpalgaon Dhage village in Nanded district of south central Maharashtra.

Tukaram dropped out after grade IX and over the next 17 years, toiled on a 6.5-acre field, raising soya bean and jowar. He oversaw the education of his siblings, marriages of his sisters, built a pucca house for his family last year and had planned to install pipelines to irrigate his fields.

But the plummeting income from agriculture, hit by successive droughts in this part of Maharashtra, meant that he had to take multiple loans to meet these expenses. He owed lenders over Rs 350,000.

“For years, he bore the entire burden alone and insulated the rest of us from financial hardships,” said Govind, his brother. “He dealt with all the loan papers too (by himself).”

He pointed to the spot under a tree where Tukaram would sit dejected for hours worrying about the unpaid loans. “In the last eight days of his life, he could barely work. He had even stopped eating properly.”

But Tukaram had found the energy to visit the village computer centre every day to check if his name appeared on the list of beneficiaries under the Maharashtra government’s loan waiver scheme.

On the afternoon of October 23, 2017, Tukaram, 32, jumped into a well and ended his life. It was five days since he had found that he was not to benefit from the scheme.

Three more applicants who did not make it to the list in Nanded and Parbhani districts in Marathwada–Maharashtra’s worst drought-hit region–committed suicide in the same week. All four had been stressed because they couldn’t repay loans taken from banks and other sources, said police reports.

Across the state, 991 suicides have been recorded between June and September, 2017, the time that it took the government to put in place its loan-waiver policy.

| Farmer Suicides In Maharashtra, June-September 2017 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Region | Districts | Suicides |

| Marathwada | Aurangabad, Nanded, Latur, Beed, Parbhani, Osmanabad, Hingoli, Jalna | 322 |

| Vidarbha | Amravati, Yavatmal, Wardha, Buldhana, Washim, Akola, Chandrapur, Nagpur, Bhandara, Gondia, Gadchiroli | 455 |

| Northern Maharasthra | Nashik, Nandurbar, Dhule, Ahmednagar, Jalgaon | 176 |

| Western Maharashtra | Kolhapur, Pune, Sangli, Satara, Solapur | 35 |

| Konkan | Thane, Palghar, Raigad, Ratnagiri, Sindhudurg, Mumbai City, Mumbai Suburban | 3 |

Source: Data collected from department of revenue, relief and rehabilitation, Maharashtra

“Yadeet pan naavnahiala. Ata kasakaraycha? (Our name is not on the list, what do we do?),” Govind recalled his brother repeating to himself in the days leading up to his death.

In June 2017, Maharashtra’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government announced it would waive loans of Rs 34,022 crore for 8.9 million farmers. But five months, lengthy procedures and the withdrawal of a faulty list later, the government finalised a first list of just 239,000 beneficiaries on October 27, 2017.

No timeline was set to return loans to beneficiaries and issue the next list of beneficiaries.

Since 2012, successive droughts, hailstorms and erratic rainfall in Marathwada have caused failure every cropping season. Farmers in Nanded said their incomes incomes halved over the past six years, as costs of seeds, fertilisers and pesticides increased 30%.

Online process, glitches, red tape: Why the scheme stumbled

The loan waivers arrived after farmer protests in June 2017. But it has failed at numerous levels.

The scheme demanded a digital application from a population that is unused to online transactions. “The government could have accepted paper forms and their own staff could have entered them online,” said Eknath Tidke, a Nanded journalist who has reported extensively on agriculture in Marathi.

Farmers have intensive work schedules and insisting that they travel long distances to a computer or common service centres is unfair, he added. Common service centres are set up by the government to provide online services for a fee.

The Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Shetkari Sanman Yojana (Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Farmers’ Honour Scheme), as the scheme is called, provides up to Rs 150,000 to be credited into the accounts of farmers who have defaulted on crop or other agricultural loans. It also provides Rs 25,000 to those who have cleared their dues.

The online application process was coupled with a biometric authentication. Farmers had to register their fingerprints to complete authentication with the Aadhaar database. And if this could not be done for some reason, a one-time password could be sent to the farmer’s mobile number to proceed with the registration.

“But this alternative authentication too required that the mobile number be linked to the Aadhaar number,” said Madhav Nagargoje, who runs a government-authorised common service centre in Malakoli village in Nanded’s Loha taluka.

Although an option of non-Aadhaar-based registration is available on the scheme’s official portal, Nagargoje said that he preferred using the direct benefit transfer and services portal to register farmers.

“A transaction through this portal provides us with a commission from the government,” he said.

Many farmers ended up being excluded from even the first step of registration and application because they could not cope with the demands of online transactions.

When the two-month deadline ended on September 24, 2017, the number of applications was down to 5.65 million, 64% of the 8.9 million farmers it was intended for.

Connectivity was also a problem in interior areas. There were days when the portal’s server would be down and farmers coming to the centre had to be turned away, Nagargoje said. Calls to the helpline brought assurances but connectivity did not improve.

Earlier this year, many were also dismayed by the move to restrict online submissions to the Prime Minister’s Crop Insurance Scheme, farmers in Nanded said. Two farmers from the district had died in the chaos that erupted as applicants queued up to enroll for the scheme on July 31, 2017, the initial deadline.

Farmers applying for the scheme were asked to submit an application and pay a premium at the beginning of every cropping season. The deadline was later extended to August 8, 2017, following the rush, but then the government switched to digital enrolment.

“The online process was adopted on the pretext of reducing corruption. But so many irregularities in the Aadhaar-based process have come to the fore,” said farm activist Raghunathdada Patil.

No timelines set for disbursing waived amounts

Even farmers who made it past the complex procedures have yet to get the waived loan amount.

On October 18, 2017, 840,000 names were displayed on the scheme’s official portal and chief minister Devendra Fadnavis and guardian ministers of districts organised ceremonies to hand out no-loan-pending certificates to some farmers. Though proclamations were made of money transfers the same day, the government later announced delays.

It also emerged that farmers who were not eligible for the scheme too had received certificates.

Finally, the list of 840,000 names was taken off the portal a few days after it was revealed that there were anomalies in the data compiled of Aadhaar and bank account numbers of beneficiaries.

“The government need not have gone about holding ceremonies and giving certificates,” said Shankar Anna Dhondge, a former Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) legislator from Nanded. “The scheme is essentially meant to be emergency relief and the government should have instead focussed on granting benefits to all those who are eligible promptly.”

There were also reports of a funds crunch with the government asking banks to utilise their funds to waive loans which would be later followed by reimbursements.

On October 27, 2017, another list of 239,000 beneficiaries was published on the scheme’s portal which now stands as the first set of beneficiaries.

| Status of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Shetkari Sanman Yojana | |

|---|---|

| Farmers that the scheme guidelines stated would cover | 8,900,000 |

| Applications received from farmers | 5,659,187 |

| Beneficiaries announced in the first list* | 840,000 |

| Beneficiaries shortlisted in the first phase** | 239,000 |

| Budget allocated to waive off loans | Rs 34,022 crore |

| Amount released till date | Rs 640 crore |

Source: Scheme guidelines, Official scheme portal, FirstPost, Hindustan Times

*on October 18, 2017 (This was taken down after a few days);

**on October 27, 2017

Banks deny govt claims that funds have been released to them

State cooperation minister Subhash Deshmukh told IndiaSpend that the government had begun transferring money to banks for loans to be waived.

“We have now cleared and finished verification of data of around 101,000 farmers who are defaulters,” he said. “Rs 640 crore in their names have now been transferred to the bank. Amounts earmarked for each beneficiary will be taken up by banks to be credited to individual accounts.”

Though the government has begun the process of releasing the money to the banks, it might still take much longer for the money to reach farmers.

“Our bank has not yet received any money under the scheme,” said a senior official at the Nanded District Cooperative Bank, requesting anonymity. “The guidelines as on October 29, 2017, were that the government would transfer the money to the ICICI bank which would then send us the names of beneficiaries along with the benefit amounts due to them.”

Asked when money would show up in bank accounts and the next list of beneficiaries would be released, Deshmukh said his government was “continuously working towards it”.

There was also a lot of repetitive processing of information. After applications from farmers with details of their bank accounts, Aadhaar numbers etc. were collected, the state cooperation department then began collecting the same data from the banks. The process of matching and cross-verifying both data sets was undertaken, thereafter.

In Kakandi, farmers await crop damage compensation along with loan waiver

Farms in Kakandi village, situated off National Highway 161, in Nanded taluka and district are dotted with harvested soya bean stacks. But, much of the produce is decayed and for every quintal of harvest, only 50 to 60 kg is likely to be bought, said farmers.

In August and September, floods from the backwaters of Godavari river had inundated fields owned by almost all of the 250-odd households in the village.

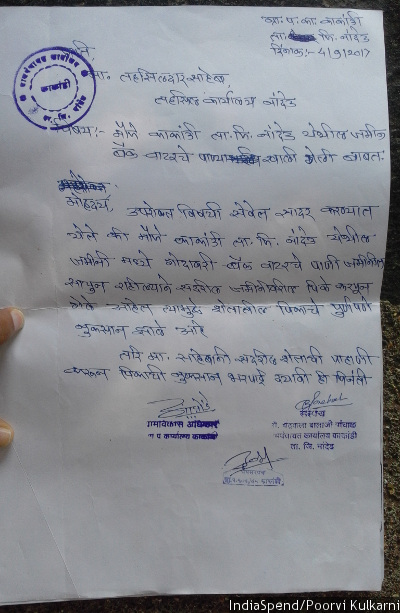

A gram sabha resolution and a collective complaint from Kakandi residents submitted to the tahsildar and taluka agriculture office seeking inspections and subsequent compensation for the crop damage went unheeded. They had also faxed their complaint to the insurance company. But neither the agriculture department nor the insurance company officials inspected the damage in time.

The resolution of the Kakandi gram sabha, Nanded district, dated September 4, 2017, demanding that the government inspect their waterlogged fields, a pre-requisite for compensation for damaged crops.

“We did receive a complaint of crop damage due to floods from farmers. But due to workload, we could carry out inspection of the losses on October 26, 2017,” said TM Ghatul, circle agriculture officer. “But the soil on the farms had not been eroded which showed that water had flowed past not causing much damage. And, also because crops were not standing when we visited, we could not ascertain damage in the way that farmers claimed.”

Low soya prices meant waivers don’t mean much

Soya bean farmers across Nanded also called attention to how price for the crop had remained low making it impossible for farmers to meet cultivation costs, let alone earn a profit margin.

“My brother only knew that the soya bean yield from his farm wouldn’t give him adequate income. He did not have much expectation from the loan waiver,” said Harichandra Pawar, 25, a resident of Kakandi.

His elder brother, Khanderao, 32, hanged himself to death on his farm on October 25, 2017. He is survived by his wife, Jyoti, and two sons aged seven and four.

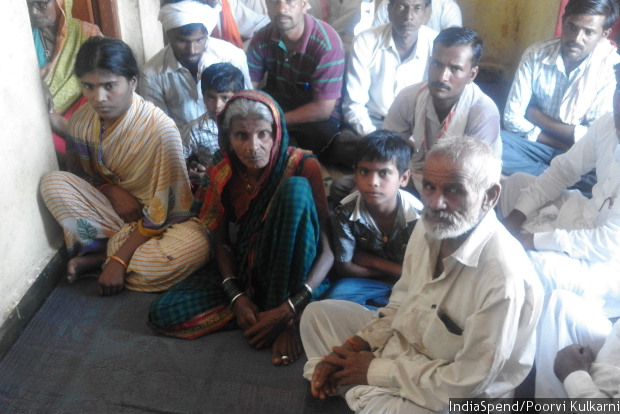

Khanderao Pawar’s surviving family. From right: Father, Sambhaji Pawar, 65, older son, Rishikesh, 7, mother, Girijabai, 60 and wife, Jyoti, 25. Behind: Younger son, Gangaprasad, 4 and younger brother, Harichandra, 25.

Khanderao had defaulted on a crop loan of Rs 45,000 that he had taken from the State Bank of India in 2011. A loan of Rs 55,000 from the Nanded District Central Cooperative Bank in his father Sambhaji Pawar’s name is yet to be repaid as well.

An old photo of Khanderao Pawar (second from right) with his family. Khanderao, 32, a soyabean farmer from Kakandi village, Nanded district, hanged himself on October 25, 2017. He had outstanding bank loans up to Rs 100,000 apart from loans taken from private moneylenders.

Both Khanderao and his father had applied for the loan waiver scheme on September 10 and 14, 2017. Of the 777 applicants from Kakandi, only two made it to the first beneficiaries’ list.

Sambhaji Pawar, 60, displays the water pump that his dead son, Khanderao, installed for Rs 50,000 to irrigate their farm. The pump broke down as floodwaters from the Godavari river submerged their fields in August 2017.

Farmers were of the view that fairer prices for their produce would be more helpful than any subsidy or loan waiver. “In the past, the price of cotton had soared up to Rs 6,600 per quintal and that of soya bean to Rs 6,400. But today, we just get Rs 4,100 for cotton and Rs 1,500 for soya bean,” said Dnyaneshwar Gite, a farmer from Malakoli.

The government had not processed any of the other promised beneficiary-oriented subsidy schemes either, said Jalindar Kagne, sarpanch of Malakoli village in Nanded’s Loha taluka. “We had held four gram sabhas in March to finalise lists of beneficiaries for more than ten subsidy schemes including poultry shed, orchard plantations and irrigation systems. But, none of these resolutions that we had forwarded were acted upon,” he said.

With majority of the farms dependent on rainfall, Kagne added that “timely delivery” of state welfare was crucial for the farm sector.

(Kulkarni is a Mumbai-based freelance journalist.)

Published with permission from IndiaSpend.