A year ago, death knocked on the doors of a university in Hyderabad. Rohith Vemula, a 27 year old student, chose death over a life of humiliation. “My birth is my fatal accident”, he said in a note that exposed an unequal society. His death woke us from our slumber of complacency, laid bare our complicity in silence, and tore down the walls of privilege. This privilege has been strengthened by years of denial. Vemula reminded us that we have failed to create a democratic society.

Now, a year later, let us look at each life lost, each family devastated, each history erased in the struggle against discrimination. Let us not rest till we achieve a truly democratic, caste-less society. For every life that refused to remain “a vote, a number, a thing”; for every young mind that was snuffed too soon; for every voice that confronted Brahmanism, imperialism, feudalism, patriarchy and fascism, we remember them. We unite and fight for every Rohith.

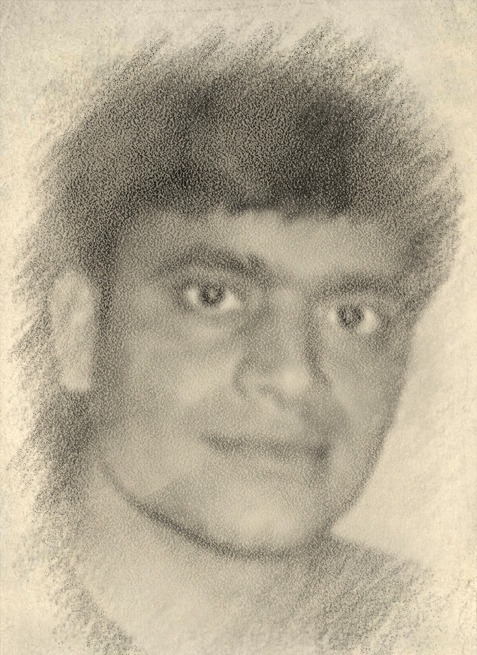

For a Dalit scholar who died fighting against an institution that was set to fail him

Senthil Kumar belonged to a sub caste of the Dalits named ‘Panniyandi’, and was a student of Hyderabad Central University. He was one of the first to pursue a doctorate from his community. However, because he was from a reserved category, Senthil faced severe discrimination to the extent that he wasn’t even allotted a supervisor. The minimum pass mark for course work examinations was intentionally raised for Dalit students so that they failed and abandoned their studies in distress, said S.Thennarasu, a research student, studying in the same university. In 2008, his dead body was found in his room. The institution initially claimed the cause of death was a heart attack, but it was in reality because of poisoning. This raised the question of institutional discrimination on the basis of caste. Although the committee that was set up eventually absolved the authorities in their final findings, the report highlighted the severity of institutionalised caste discrimination on campus.

For a bright mind that refused a life of half-existence

On the 30th of March 2010, Bal Mukund Bharti killed himself successfully. A final year student of MBBS in AIIMS, Bal Mukund had attempted suicide a day earlier but was saved by his friends. He was from Tikamgarh in Bundelkhand, Madhya Pradesh. He repeatedly faced casteist prejudices by the faculty members in AIIMS who felt that a harijan or adivasi did not deserve to study medicine. Coming from a poor family, his parents had taken heavy loans so that he could pursue higher education. He had cleared the entrance for AIIMS, IIT and the CPMT exam in the same year but chose to pursue his career in medicine with the hope of moving out of the shadow of his caste. Instead, he faced a hostile environment in AIIMS. This hostility came not just from his department but even his hostel. The principal openly claimed that harijans or adivasis did not have the brains for medicine. Whenever he asked questions in class, the teachers did not find them worthy of any response. He was asked to sit at the back of the class. He was graded down in his practical exams by the instructors. He was even asked to move from his allotted hostel room to another one with other SC/ST students. Despite this, a few days before he killed himself, he had purchased books worth thousands of rupees hoping to complete his education and leave the country that discriminated against him because of his caste. But, in the end, the harassment and humiliation proved too much for this bright mind and he chose death to what can only be described as a life of half-existence.

For an adivasi boy who reached AIIMS but found himself alone in a sea of privilege

Anil Meena belonged to a tribal family of agriculturists, and had qualified the entrance exam to the prestigious All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). However within two years of his stay, he committed suicide at the age of 22. Students like Anil Meena were deliberately neglected by the teachers and authorities in AIIMS because they belonged to the reserved category. Anil Meena was not allowed to write his exams as he was short on attendance. Interestingly, only students belonging to the SC/ST category were not allowed to write the exams due to low attendance, whereas other students belonging to the General category were allowed to sit. In 2006, the Indian government constituted a three-member inquiry committee under the chairmanship of Professor S.K. Thorat, the then UGC chairperson, to look into the complaints of Dalit and Adivasi students of AIIMS. The systematic segregation on caste lines in hostel with SC/ST students being forced to shift to the two top floors of Hostels 4 and 5, after sustained pressure, humiliation, abuse and even violence by 'upper' caste students, should be a matter of great shame for a premier institution like AIIMS. “Being a doctor is not just being in a profession, what comes with it is also culture capital, and a denting of traditional caste roles”, says Gurinder Singh Azad, a student coordinator.

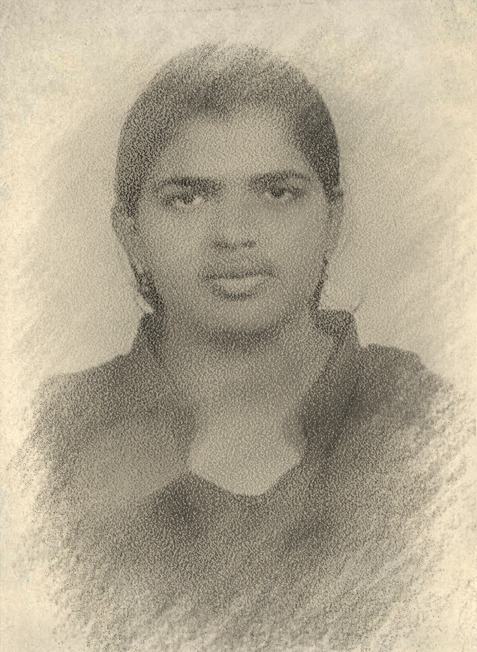

For the minor Dalit girl found raped and killed in a water tank in Rajasthan

Delta Meghwal, a 17 year old girl from Barmer in Rajasthan, pursuing a teachers training course in Nokha in Bikaner, was a quite a prodigy. At the age of seven, she was awarded by the government of Rajasthan for her artwork. Her last days were spent in the hostel of the Jain Adarsh Teacher Training Institute for Girls. Under the instruction of the hostel warden, Priya Shukla, she was forced to clean the hostel premises and regularly faced casteist slurs by the authorities. On the evening of 28th March 2016, she was asked by the warden to go to her PT instructor Vijendra Kumar’s room in order to clean it. There were only three other girls in the hostel at the time. Most hadn’t returned after the Holi vacations. In Vijendra Kumar’s room she was sexually abused for hours. Late at night, when the others in the hostel went looking for her, the warden knocked on the door of the PT instructors’ room. When he answered, it was apparent that Delta, a minor who was still in his room, had been raped. Instead of addressing this, the officials of the institution arranged for both the PT instructor and Delta to write a maafinama (letter of apology) wherein they were made to claim that the physical relationship was consensual. The next day, a worker of the school found Delta’s body in the water tank of the hostel. The police was informed and two constables arrived and arranged for her body to be removed from the tank. They carried her body in a municipal garbage disposal truck, without a ‘Panchnama’ or any documentation of the process on video, as is the procedure. An FIR was filed a day after her body was found. On the insistence of Delta’s parents, the FIR named the warden, her husband, the PT instructor and the principal of the institution responsible for the death of their daughter. After an outcry from across the country, the warden, PT Teacher, and principal were booked for her death.

For the 29 year old Dalit law student raped and killed in Kerala

Jisha, 29 year old law student in the Government Law College in Ernakulam in Kerala, was raped and killed on 28th April 2016 by a migrant labourer in Perumbavoor. She was brutally hacked to death. Raped, killed using sharp objects, then stabbed over 30 times, Jisha’s body was severely mutilated when found by her mother Rajeshwari. The mother and daughter lived in a small home in purampokku land (land liable to be submerged when the canal is full) in an area surrounded by palatial homes belonging to Nairs and Christians. This duo was ostracised by the neighbourhood citing the mother’s unusual behaviour over the years. On closer inspection, it was found that this family of two living in a shack next to a canal did not even have basic utilities in their house. Living out of little boxes, without a toilet or a bathroom, and estranged from their extended family, they kept to themselves. A quick glimpse at the history of the family in the area reminds us that Rajeswari, the mother, had strived to protect her daughter through thick and thin. In the past, when Jisha was harassed, injured, attacked or their home pelted with stones, Rajeshwari has filed police complaints several times. Jisha, on her part, strove to complete her education. She hoped to save enough money to purchase land and build a pakka home for the two of them. Early in her life, Jisha’s father abandoned the family. When Jisha’s elder sister Deepa moved away from the family to marry, Jisha and Rajeshwari were left to fend for themselves. The wealthy, high caste neighbours wanted nothing to do with the family, they had no idea of the way the mother and daughter survived and vehemently denied having discriminated against them over the years. Only after Jisha’s classmates in the Government Law College and human rights activists raised the issue, did this brutal murder come to light. Following an outcry from across the state, the Kerala police nabbed the man who killed Jisha.

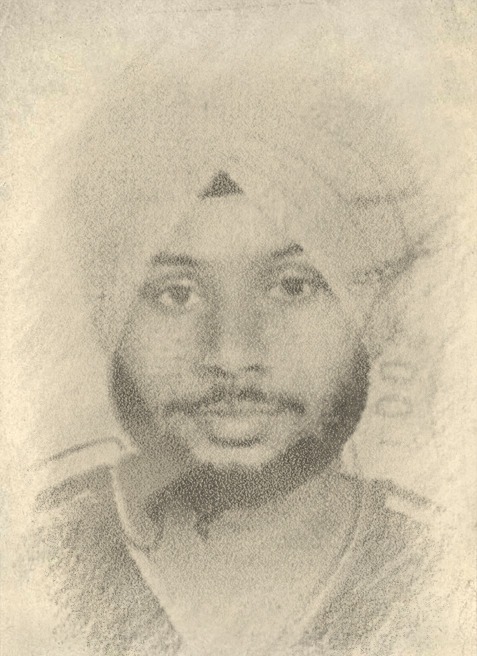

For a man disqualified for his caste and not merit

Dr Jaspreet Singh committed suicide in 2008 because of harassment. He failed to clear his exams because of the casteist behavior of one professor who taught him in his fourth year in Government Medical College, Chandigarh. He was a Dalit student from a very humble background and had successfully cleared all papers without fail until his fourth year when he was under a professor whose criteria of assessment was Jaspreet’s caste rather than his academic performance. The professor humiliated him on caste lines and threatened to continually fail him in his papers. “Do whatever you can do, I will make you to do your MBBS all over again”, taunted Prof N.K. Goel, Head of Department, Community Medicine. Jaspreet had left a suicide note in the library naming the professor and revealing his casteist behaviour. The exam in which the professor had failed Jaspreet Singh was later sent for reevaluation, and he was given a passing mark.

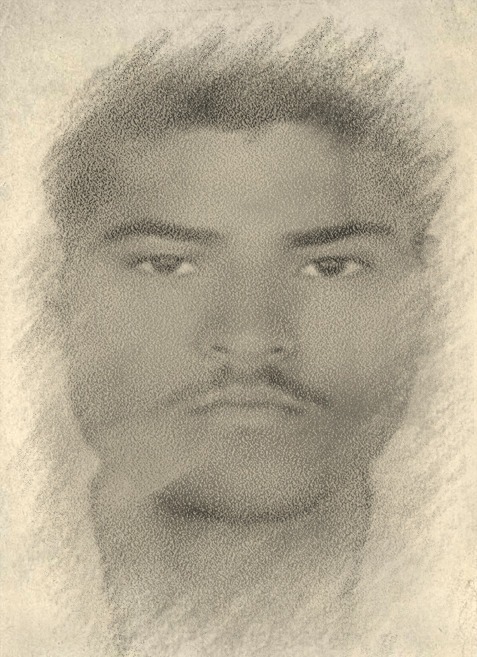

For a Dalit harassed by the University for being ‘chamar’

Manish Kumar Guddolian, studying in the Department of Computer Science and Technology of IIT Rourkee, committed suicide at the age of 20 in 2011. Both IIT Roorkee and Roorkee police attributed his death to his inability to cope with academic pressure. However, the truth is that he was unable to tolerate caste assaults against him by his own classmates, and the insensitive attitude of the hostel warden forced him to live outside IIT Roorkee. The institution also made his father sign a false statement that he didn’t want an enquiry into the death. Manish's parents have alleged that he faced caste-based harassment throughout his stay at IIT. Their testimony has been recorded on camera by Insight Foundation, an activist group which aims to protect the rights of SC/ST students. The recording is part of a documentary series which has already documented two cases of suicide of Dalit students in medical colleges. Manish's mother, Bhanmati, has said in the documentary: "They used to call him a chamar and asked insulting questions like 'Do chamars have the capacity to study?'" Manish had to shift outside the hostel, undergo psychiatric treatment, drop a semester, and rejoin the course. And then, after years of marginalisation and humiliation, he killed himself.

For a mother without a son, the dream of IIT stopped short because of caste

Aniket Ambhore was a Dalit student in IIT Bombay who committed suicide in 2014, and was discriminated against on the basis of his caste. His parents had submitted a 10 page testimony to the Director of IIT Bombay, elaborating the kind of caste discrimination he faced in his life. An inquiry committee was eventually set up. However, its findings was never made public. Ambhore’s mother said, “Students’ agitation is the only hope remaining. Perhaps only the students will be able to wake up the dormant system. We are waiting to find some solace for the pain suffered by Rohith’s family and the Dalit society.”

For three Dalit girls driven to suicide after being pressed to pay excess fees

Three 19 year old girls, V Priyanka, E Saranya and T Monisha, studying Naturopathy in SVS Yoga Medical College in Kallakurichi, near Villupuram, committed suicide to escape the torture they faced at the hands of the college chairperson Vasuki Subramaniam. They were aware that their decision to kill themselves could bring to light the excesses of the chairperson. They felt cheated by an institution that was determined to extract money without providing education. Their suicide note preempts the attempts that would be made by this chairperson to discredit their account by calling these girls ‘characterless’. Yet, in their death, they hoped that this act would expose the extortionist institution and force the authorities to take action against the chairperson. This suicide was preceded by a long series of protests by students of the college demanding basic facilities like adequate teachers, bills for each payment made, and a stop to the hiking of fees. Instead of addressing the concerns of the students raised over several years, including several attempts by students to commit suicide in 2015, the authorities, including the state government, turned a blind eye to the violations of the management.

For Rohith who refused to be reduced “to a vote, to a number, to a thing”

Rohith Vemula was one of the five Dalit scholars suspended from Hyderabad Central University last year, in an extreme case of caste discrimination. This led led him to commit suicide on the 17th of January in 2016. His death triggered a series of reactions from all over the world and has brought to the front the widespread issue of caste discrimination in institutes of higher education in India. Sadly, the only reaction from the government has been to try to prove that the student was not a Dalit but an OBC, thus entirely diverting the focus away from relentless caste-based institutional discrimination.

The onus is on us to take a stand and not let his struggle against oppressive regimes be in vain. We need to emphasise that this is not simply the death of a Dalit, but a human being and fellow student who was methodically discriminated against, as are many more in various other institutions all over the country.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum