Border was released in 1997, I was five years old then. I do not remember watching the film on screen, but I do remember that on fancy dress competition in school that year, most children came dressed as faujis.

Growing up, it became impossible to miss the cult status that the film had acquired because “To Chaloon” would routinely play on radio stations and the film regularly televised on Doordarshan (and Zee Cinema).

I come from a family of all sons and brothers. My brother, who is three years younger to me swears by Border. He still remembers the dialogues by heart. My understanding of the reality of the war that was came from the film. Border was my history textbook. My brother’s Bible. The Bible of the million Indian (men).

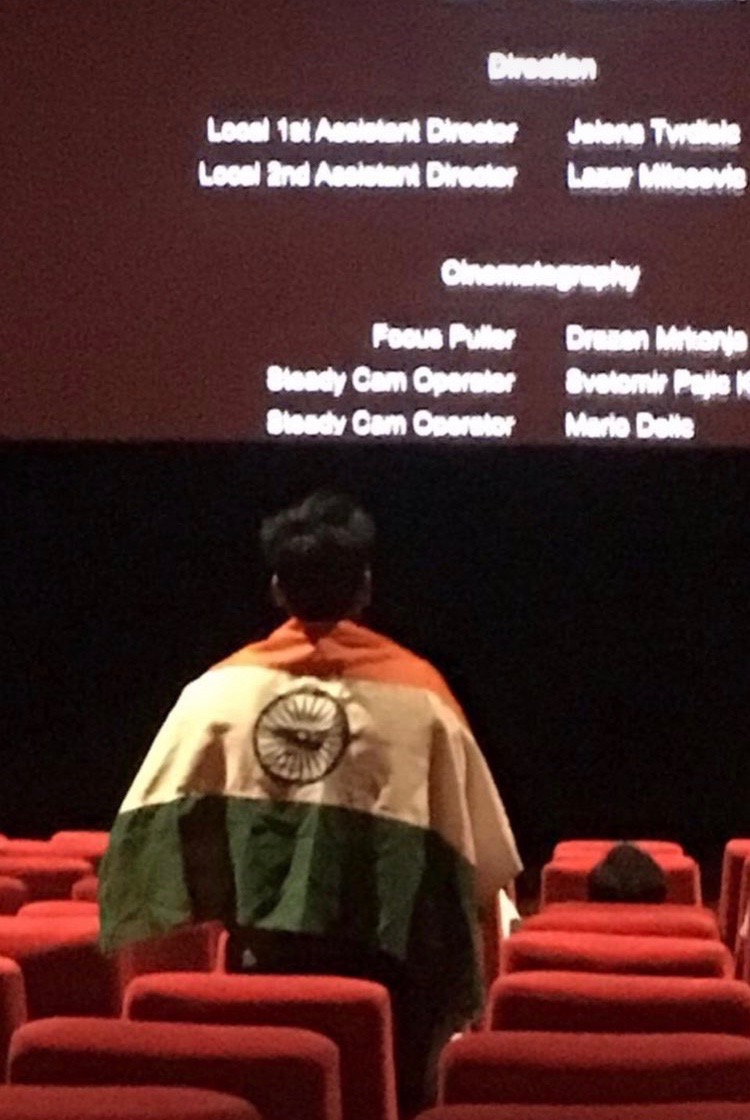

In 2016, Border was screened retrospectively at the Independence Day Film Festival, jointly presented by the Indian Directorate of Film Festivals and Ministry of Defense, commemorating the 70th Indian Independence Day.

Uri released in 2019, I am eleven years older and wiser. Considering the essential truths that are communicated in both films remain the same, mustn’t we ask: Is Uri the Border of the twenty-first century?

I will not begin this discussion with an analysis of fact and fiction. Such a conversation is utterly unsuitable for the Indian context/ viewership. We hail from a tradition of oral storytelling. We are a sucker for the tale and the fantasy. Films are spellbinding for us. The willing suspension of disbelief is not a choice for us, it is a way of living. Films satisfy our senses, the same way as religion satisfies our soul. And therefore, it means little to the common viewer, an ardent Whatsapp user, if Uri, a film made up some facts? The message has always preceded the medium, and the overlaps don’t seem to mind us.

I will not contest if Uri is a propaganda film. There are no two ways about that, but is it as much a propaganda film as Lagaan or Sanju, or even Ben Kingsley’s Gandhi? The answer to that question can be determined through a consideration of these concepts: intention, funding/production, and the aftermath. I leave it to the reader’s better judgement.

A famous novelist, when asked about the political aspects of his work, said, “Religion is organized to satisfy and guide the soul—politics does the same thing for the body.” In a democracy, he said, “when a politician persuades or shoots people in a time of tumult… he gives great power to the spellbinder, the artist in words, the preacher, the demagogue, whatever you call him”. For him, if Rousseau, Marx, Tolstoy, were great spellbinders of words, then even a businessman or a crook was a spellbinder and a man of imagination. He added that “Poets have started most of the revolutions, especially nationalist revolutions. On the other hand, life would die without poets, and democracy must have its spellbinders.” It is not a coincidence that the BJP followers are unironically called Bhakts.

Uri is produced by the entrepreneur with a Midas touch, Ronnie Screwvala under the banner of RSVP films. Screwvala said that the film has elements of “war, action, and strategy based on a true story” that the “Indian audience is yet to watch such experience in cinema,” and it shows. The cinematography is slick, and why won’t it be? Uri’s lead actors and the supporting cast were trained at Mumbai’s Navy Nagar with Captains and Majors teaching them slithering, using arms and ammunition and other drills used by the armed forces.

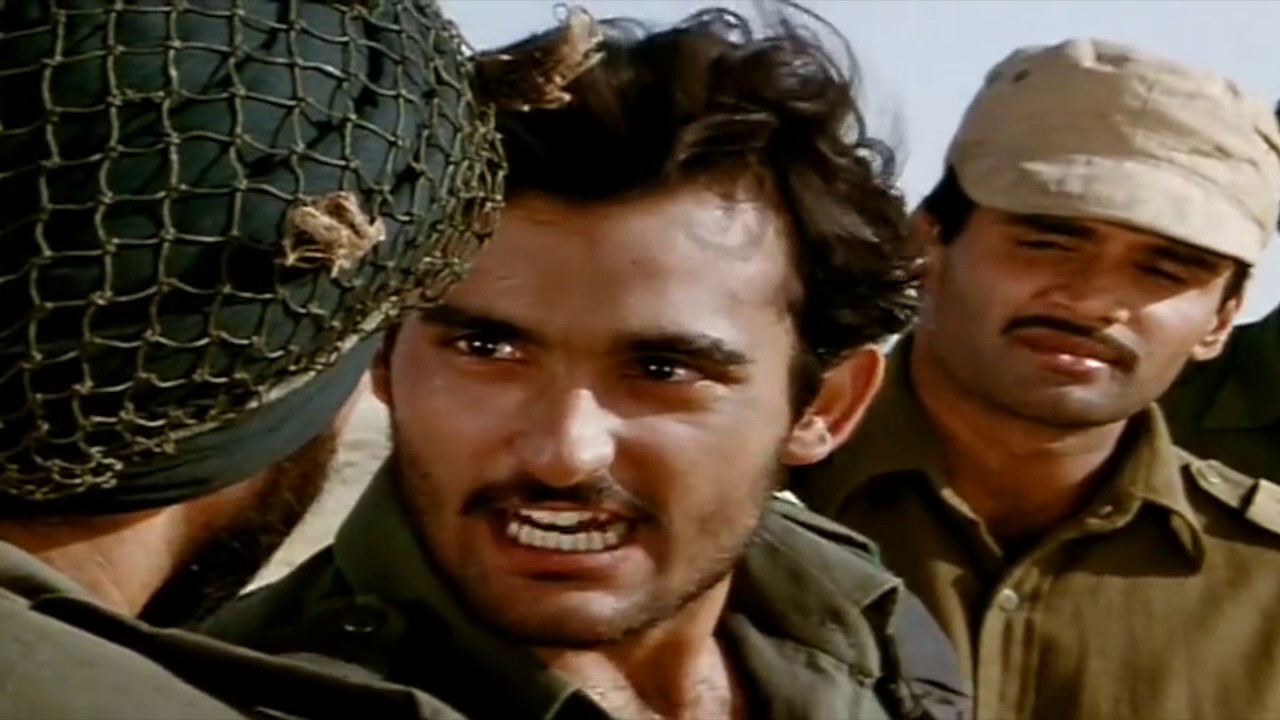

Image Courtesy: Rediff

Vicky Kaushal is always introduced in a flattering light, and costume that accentuate for his muscular body. The long-bottomed shorts of the men in uniform, pacing their steps or running has for long remained spectator lust-worthy. Uri lures, charms and intoxicates. It turns non-believers into believers. It could easily pass for an advertisement for the forces if it didn’t already.

The music score is catchy. In case you’re wondering what real impact, a music score can have in such a film, know that in addition to the “Best Feature Film on National Integration” Border (also) won “Best Lyrics”, “for its evocative wording that is imbued with compassion for our nation and for human beings at large” (Award Citation), and Hariharan won the best playback for “Mere Dushman“. This was at the 45th National Awards, whatever remained to win was made up in abundance by the Filmfare Awards. But unlike Border, where all songs were first-person accounts, lip-synced by the actors, Uri only has songs in the background, in a third person voice. This shrewd cinematic tactic that implies everything without ostensibly saying anything is the guiding principle of Uri: A Surgical Strike.

For a film made on war cry – Uri exercises tremendous restraint in the first quarter. The first thirty-forty minutes is calm and composed storytelling. Vihaan (Vicky Kaushal) is going about his everyday business, celebrating his niece’s birthday, chilling with his friends, and taking care of his mother. He is made to look so ‘relatable’ that if we didn’t already know what we came for, we could see easily mistake him for a regular boy doing any other job. The last decade in Hindi cinema, has recorded a surge of the “relatable” character-driven films which has been identified by the ‘alternate’ within the mainstream as a new-voice in storytelling. The producers, creators, and exalted consumers of this cinema have celebrated it as a reactionary movement against the fabulous, out-of-this-world genre of cinema popularized from the 1990s. Obviously, there is a lack of nuance, and the question – relatable to whom? Looms large, but Uri is not the film to dwell on that. The ‘naya’ in the ‘naya Hindustan’ is only too happy to play to the galleries.

Image Courtesy: YouTube

Watching Uri, I felt that Major Vihaan Singh Shergill was the grown-up version of Border’s Lt. Dharamvir Singh Bhan, played by Akshay Khanna, who unlike Dharam Bhan survived the war, with the same unresolved issues (of toxic masculinity) so he could one day lead the Surgical attack at Uri. It was important that he not overcome his trauma, for it would provide the fodder that fuels his passion. From a young poor, rural boy who whose stomach gave away at the ‘mere sight’ of a dead enemy, who had been forced into the army to honour his father’s wish, was now an educated, sophisticated, urban army officer for whom the forces stood for courage and was his one true calling. Today, a hero isn’t a hero without a conflict, and therefore, it is Dharam, with his ailing but proud mother and his wrestle between private duty and public morality that finds manifestation in Vihaan. In an authoritarian moral universe of men, courage defines character. A writer who served fifteen years as a political prison compiled a diary of fragmentary lessons he learnt in jail. Point Number Thirty read something like this, “I discovered that the world should be divided not into good and bad people but into cowards and non-cowards.” The diary was titled, “Forty-Five Things I Learned in the Gulag.”

Image Courtesy: ScoopWhoop

Like Kuldip Singh of Border, played by Sunny Deol, Vihaan is a product of his time. Kuldip was what we would immediately label a misogynist and fundamentalist today, but he laid the foundations of the Sangathan. He belonged to the earlier phase of the movement, for whom the lines between courage and fanaticism were blurred. Both demanded faith and he was a fiercely loyal devotee. A chest-thumping patriotism was the need of the hour. It was crucial to establish who the enemy was. Today, that narrative has been ingrained too deeply to be shaken. For Vihaan, the citizen or the devotee do not exist as distinct, independent figures. He is what Uma Bhrugubanda calls citizen-devotee. He swears allegiance not simply to a particular faith but is mediated by rationalities of power, the discourse of rights and justice, governance and so on. The chants of Bharat Mata Ki Jai have been replaced by the milder Jai Hind, to an encoring audience that sings the national anthem before any film. The difference between Vihaan and Kuldip lies in the degrees of fanaticism.

Image Courtesy: RSVP Films Instagram Handle

In the nationalistic films of the nineties or the early 2000s, the heads of the state like the PM or the President were considered too sacred to be given a human form. Even in a film like My Name is Khan (2010) the face of the actor playing the American President was concealed. One had to earn that darshan. Uri subverts this but even its cinematic subversion is tainted with conformity.

We are aware that the BJP campaigns, both pre and post-election are designed around a single man. Modi is the mind, body and soul of the party, and the nation by default and all ads, posters testify to that. Uri concedes too. But the question arises, is an actor worthy enough to play Modi? It was clear that Modi could only be played by an actor of repute, but also one who had a certain ‘following’. Rajit Kapur, the man who played Gandhi in Shyam Benegal’s The Making of the Mahatma is bestowed with the national honour of playing PM Modi on screen. An addition of such imminence to one’s filmography makes one a strong contender for a National award or two1. He is a fine actor, and it is impossible to forget seeing him on screen. Therefore, I was surprised that even though I remembered him occupying a presence in a significant number of scenes, yet I did not remember him particularly saying a thing of real significance. And that’s where it struck me, his ‘blending’ made him the perfect Modi! He is not the PM who suggests the surgical-strike, he is but the compassionate leader who listens to his flock, exercises restraint and patience, is moved by conviction and rewards many folds. He’s not the wrathful God of the Old Testament, He’s the one who sent His son on war. This camouflage evinces Bollywood’s a-political leanings on all issues. Even though a no-response is a response, yet it is easy to evade as no records exist to prove otherwise.

Uri, sure, gets a lot of things ‘right’. It understands the socio-political and economic climate it is set in, both at the local and global level and is careful to not make lazy mistakes that could throw off the relatively woke-r audience. Everything is made palatable. In Border, Tabu(Kuldip Singh’s wife) starts crying not even five minutes into the film, culminating in a scene that makes Kuldeep Singh’s misogyny as nationalism even more pronounced. Not once, does the film show the couple looking into each other’s eyes. Tabu is always either sitting or hugging his waist in remorse, as he continues to literally, cinematically and symbolically, look down upon her.

Image Courtesy: IMDb

Uri is evolved. For instance, Vihaan has a niece who takes judo lessons and hero-worships her uncle. One of the outcomes of the global movement on women’s rights* (restraining from using the F word that alienates readers) on mainstream Hindi cinema is that in films, a child now stands for a daughter, not a son. This new norm is an affirmative statement in a nation infamous for perpetuating violence against women through female feticide and female infanticide.

In Border, the memory of a home crops up only through flashbacks. The ties that tether a soldier to domesticity come in the way of his higher goal. Uri, by contrast, smartly employs the first thirty minutes establishing Vihaan’s conduct at home. Since family is the microcosm of the nation-state, his attitude at home reflects his attitude toward the nation. His home is a female-dominated sphere which may be a progressive statement to make, but tokenism is not enough anymore. The muted presence of the actor playing Sushma Swaraj at the PM’s conference table in Uri is the same role played by Bollywood in the #MeToo movement, that of silent spectators. Even Seerat Kaur(Keerti Kulhari), a fellow officer in the Air Force is a Veerangana. She isn’t a sad pitiful wife but is a Veerangana all the same. Vicky is shown as a sensitive leader and an evolved man who does more listening than talking. He only begins to lose it after his mother, an Alzheimer’s patient, wanders off and isn’t found till evening. That’s when his protectiveness of the mother and motherland become defined. He roars into Yami Gautam’s face and that’s when the facade drops. But in forty minutes, he has already established himself as a sanskari son, a protective brother.

Uri advances the same myths that Border introduced. In the moral universe of Hindu right and wrong, it is important to assert that Pakistan is the snake which always attacked first. For a film on surgical strike, this information becomes all the more crucial. The cut had to be made too deep to incite revenge which Mohit Raina’s death solidified. The farz then was to defend the brothers, not the mothers or sisters. But unlike what we recite in our constitutional pledges, in the “naya Hindustan”, not all Indians are our brothers and sisters.

Both Border and Uri showcase an all Hindu army, overshadowed by a Punjabi-Sikh dominance, and restricted to an upper-caste North Indian representation. In Border, Rathod (Suniel Shetty) extricates a prayer cap clad villager’s Quran from his scorched hut, doing him a huge favour and fulfilling the true Dharma of a Hindu, which is to sacrifice oneself for the upliftment of the downtrodden, he tells the now-homeless man. Set more than a decade apart, Uri demonstrates its “tolerance” with a hit-and-miss scene of three Muslim soldiers offering Namaz as Vihaan lurks by. The gaze of a standing Vihaan on the prostrating devotes is not a gaze of equality, let alone camaraderie. It is a gaze that begets terror and shows the marginalized, almost invisible position of Muslim minorities.

In films with clear enemies, heroism is validated by defeating an equally strong, if not stronger enemy. Usually, the enemy is shown as a pure evil force, which heightens the suspense so the release is all the more cathartic. I have always been curious to ask the actors who play Pakistanis or a Muslim terrorist in a nationalist film about the briefs given to them by the director. In Uri, the evil character is replaced by a lampoon. Our first encounter with a Pakistani official in the film comes through a burping Rakesh Bedi who finds it hard to note a simple phone message as a result of his “std” (acidity). The important thing was that the soldiers fulfil their promise of “ghar mein ghuss ke maarna” which they did. Unlike Border, which allegedly was an anti-war film, where most characters die, Uri prides itself on killings with no casualty. The “naya Hindustan” has no patience for introspection. It likes its revenge like it likes its noodles, instant, fiery and served on a platter.

1. In a post-Deewar era, the measure of a good actor in Hindi cinema is determined by three things: dependability, one-upmanship, and reliability Even this could be understood in terms of a transaction involving matters of wealth and faith. Dependability translated into making the audience buy a ticket and holds tremendous importance for producers. In matters of faith, it extends to the maanyeta attached with to god who gets the flock to the temple. Reliability is the transaction that exists between the god and the devotee, or the audience and their hero. It bears the silent promise of deliverance. In simple terms, it is the faith on the actor, to give his viewer his money’s worth; a two-way bond founded on familiarity, kinship and loyalty. The third aspect of the one-upmanship is the ability that makes gods of men. It is the final stage of devotion wherein the devotee seeks nothing but everlasting darshan. At that point, all fear, doubt, logic has been surrendered. The devotee exists as a mere shadow of the deity. Most good actors are a combination of any two qualities, combine all three and you get a superstar. Rajit Kapur did none of the above, but in doing so he revealed a facet of acting that I had never paid attention to before – the quality of blending.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum