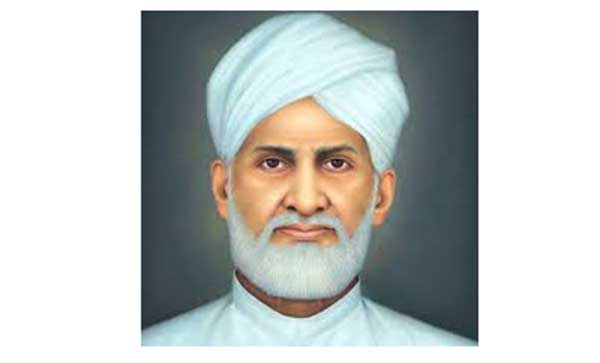

Vakkom Moulavi

The Vaikom Satyagraha was a major event for mobilising subaltern resurgence in the princely state of Travancore in South Kerala, in the 1920s. The Dalawakulam Massacre acted as a flash point. TK Madhavanmoved a resolution for eradicating the practice of untouchability in the Kakkinada session of the Indian National Congress in 1923. The temple entry agitation in Vaikom, under the leadership of Madhavan, was a direct offshoot of this. Despite limitations, this was a watershed moment in the history of modern Kerala.

The contemporary mainstream social imagination in Kerala remains elusive to the Muslim, despite material progress. They occupy a social space analogous to the relatively well off, yet socially subjugated Ezhavas of 1920. The pattern of this irony, is a familiar one in Kerala. A reprise of the Vaikom Satyagraha, as providing universal access to mainstream social space, giving entry to everyone, seems possible.

Unlike most popular presentations of the narrative of the Vaikom Satyagraha, the temple entry movement envisaged access to the approach roads to the temple and not to the structure itself. The situation was rife such that adherents of semitic faiths could access the approach roads, even using automobiles, while those who worshipped the deity of the temple itself were denied access. The Ezhava community particularly felt the brunt of this discrimination, since unlike the other subaltern caste group, they had acquired economic heft and attained a degree of commercial success. The agency thus achieved was incommensurate with the perceived status of the community. The bhakti movement by Ezhuthachan had initiated a subaltern movement of education. Sree Narayana Guru was the major figure in the Kerala Enlightenment of the turn of the century which had other leaders like Kumaran Asan, VakkomMaulavi and Sahodaran Ayyappan. Sahodaran Ayyappan was especially vocal in his denunciation of the caste system as well as caste atrocities. He organized a `Mishrabhojanam’ (communal eating) in which children belonging to his community and other castes perceived as `lower’ dined together. VakkomMaulavi followed the latest developments in Islamic thought in countries such as Egypt and brought them to his audience in Kerala, through his journalism. Maulavi started a newspaper `Swadeshabhimani’ (Patriot) with Ramakrishna Pillai as editor. Pillai earned the wrath of the powers that be, including the Diwan of the local monarch, through his scathing critiques of courtly shenangians. He was exiled and the press was confiscated.

Vakkom Moulavi’s understanding of the government’s duty and the people’s rights also inferred active engagement of the people in the political process of Travancore. Eventually, this laid the foundation for the nationalist movement in Travancore and the campaign for a responsible government.

(Abraham, Jose. Islamic Reform and Colonial Discourse on Modernity in India: Socio-Political and Religious Thought of VakkomMoulavi )

The economic muscle acquired by the Ezhava community was at odds with their subaltern status. This was an unsustainable situation for the society as a whole. Kumaran Asan, a disciple and close confidante of Sree Narayana Guru emerged as one of the triumvirates of modern Malayalam poetry. There were other subaltern community leaders like Mahatma Ayyankali, who rode a `Villuvandi’ (Cart) through the public roads as the worthies of the time were accustomed too. He exhorted the women of his Pulaya community to abandon their stone necklaces, which were markers of `status’. A lengthy quote would perhaps help to trace the trajectory of wealth:

The government service was the preserve of caste Hindus. The alternative for the well-educated was to leave the state, and this was the course followed by the first two Ezhava graduates in Travancore. Others, less well-educated, were pushed towards trade and commerce, an area which Malayali caste-Hindus tended to avoid. By 1900 the export value of the products of the coconut palm, caring for which was the traditional occupation of Ezhavas, exceeded Rs 80 lakhs a year. The labour for the industry was overwhelmingly Ezhava, and growing numbers of Ezhavas were also becoming middlemen and petty factory owners. “Good work is being turned out here by private industry,” wrote the Travancore Dewan of an Ezhava coir factory near Quilon in 1904, “and some boys are being trained in the work… This institution speaks well for the industry and spirit of self-help of the Elava (Ezhava) community. Weaving was another traditional occupation that lent itself to small-scale capitalism. The two Ezhavas who have been chief ministers since independence in 1947 both came from families that ran modest weaving enterprises around the turn of the century.

(quoted in `Temple-Entry Movement in Travancore, 1860-1940’, Robin Jeffrey, Social Scientist, Volume 4, March 1976)

Oppression and communal subjugation operate in cycles. The Muslim community in contemporary Kerala finds itself in the same predicament as the Ezhavas in Kerala circa 1920s. Gulf migration and remittances have significantly contributed to their upliftment. Educational institutions including professional colleges have brought in a new current of female education. Despite facing hardships, Muslims of Kerala have acquired a space for themselves in the imagination of Kerala and India as a whole. The second and third generations immigrants to the Gulf countries produced a semblance of lasting wealth. This has resulted in relative prosperity for the Muslims of Kerala in comparison with other subaltern sections in the state. Their political agency, though meagre, offers some purchase in the democratic system of patronage dispensation followed in the southern state.

Despite the economic emergence of Kerala Muslims as a group, and concomitant benefits accruing from it in the economic, political and cultural arenas, they remain backward in almost all the human development indices with meagre representation in areas where the intervention of the democratic polity matters-forest, health, excise and finance. These are four areas of political significance. This semi-participation in state affairs is a major hinderance to the community’s superstructural prospects, despite its economic upsurge. Liquor which is indispensable to the logic of economic planning and analysis in Kerala, remains out of limits to the community, even in the realm of imagination. Thus, incomplete access of secularism as a concept owing to historical reasons and backwardness, have pushed the community back in the wider scheme of things in the Kerala public sphere and civil society. There are hardly any formidable civil society figures from this group. As a result, the Muslim community in contemporary Kerala occupy a position, hardly enviable, analogous to the Ezhava community of 1920. The economic base gives semblance of strength and robustness. This also could be fleeting with the pandemic curtailing remittances from the Gulf countries to India, after the repatriation of migrant labourers, most of them unskilled. But the relative economic wellbeing sits at odds with the wider socio-political, economic and cultural backwardness of this religious group.

The temple entry movement was inevitable since the subalterns of Kerala had acquired a critical mass in terms of social agency and leadership. Such a situation is missing at present. Muslims in Kerala still struggle to find a shared future with the majority of Keralites, belonging to all persuasions. It is imperative that they be introduced to the mainstream through agitprop means as well as planned interventions. The organisational factionalism and denominational disputes have hardly done any good to anyone. As the film actor Fahadh Fasil says, in the context of the film industry, `there is space here for everyone’. It is in that elusive imagined shared space that the Vaikom Satyagraha placed the erstwhile subalterns of Kerala. But `there are no castes without outcastes’. The expedited Dalitisation of Muslims in contemporary India, part of an ongoing project, has meant that a space for shared cultural imagination is not easily accessible for the Kerala Muslims. The imaginative space offered by the enlightenment heralded by Sree Narayana Guru, VakkomMaulavi and Ayyankali, was ecumenical in character and inclusive in its cultural politics. Its present-day articulations have increasingly become sectarian, withdrawing into cocoons of reified instrumental rationalism.

Bibliography:

Abraham, Jose. Islamic Reform and Colonial Discourse on Modernity in India: Socio-Political and Religious Thought of Vakkom Moulavi

Robin Jeffrey, Temple-Entry Movement in Travancore, 1860-1940’. Social Scientist, Volume 4, March 1976

*The author is a research scholar at JNU

Related:

Christian groups demand justice for Dalit minorities

Police fuelling Systemic Communalism in Kerala?

Do Dalit lives matter in India?: Reflecting on condition of Dalits and apathy