Image Courtesy:timesofindia.indiatimes.com

Image Courtesy:timesofindia.indiatimes.com

As the dominant model of economic development has led to high inequalities, increasing threats and problems for rural communities, a feeling of increasing loss of control and uncertainty for many people and colossal ecological ruin, there is a growing search worldwide for alternative patterns of development.

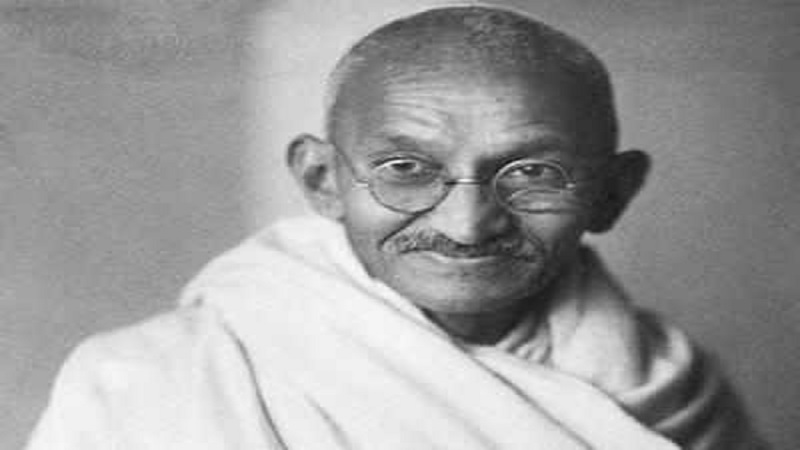

In this yearning for alternative thinking, the ideas of Mahatma Gandhi have been a constant attraction and a source of thought for present day changes. While his emphasis on voluntary simplicity and frugality are already very well-known, there are several other aspects of his economic thinking which need to be better known.

One of these relates to Mahatma Gandhi’s perception of the role of a consumer or a buyer using his strength as a consumer to bring wider economic change. For Gandhi a buyer in need of a product should not enter the market merely to maximise his satisfaction. Instead, he should be guided to a large extent by social responsibility. He unhesitatingly extorted people again and again to buy khadi (cloth which is both hand spun and hand woven) and support it, ignoring questions such as coarseness or unevenness of the fabric.

When he promoted khadi and people complained of some problems with cloth, he told them to also think of not only how good khadi is for skin but also to think about whom they are supporting with this choice and the conditions in which she works. In 1934 he wrote, “Then take the question of standardisation. You cannot enforce it in khadi. As Rajagopalachari once remarked, a poor ordinary spinner cannot always spin thread of a uniform quality. She is not a machine. Today she may be unwell, tomorrow her child may be ill and her mind may be distracted. If you have love for the poor spinner or her child, you will not insist on having smooth, even thread always, but be satisfied with what she can give, so long as she gives her best in the condition in which she finds herself at the moment.”

Earlier in 1929 he had declared, “Let it be known that there are millions in India who can work at the spinning wheel for eight hours a day, and that it is impossible for them to use all the khadi woven therefrom. It is the bounden duty of good citizens of India to take off the surplus product that is turned out by these brothers and sisters of theirs.”

Closely linked to this is the concept of ‘Swadeshi’. Literally this means ‘my country’ but Gandhi used the word in a much broader sense. Explaining this concept he wrote in 1916, “Swadeshi is that spirit in us which restricts us to the use and service of our immediate surroundings to the exclusion of the more remote. In the domain of economics, I should use only things that are produced by my immediate neighbors and serve those industries by making them efficient and complete where they might be found wanting.”

Interpreted in this way Swadeshi, will take India to a stage where every village of India will almost be a self-supporting and self-contained unit, exchanging only such necessary commodities with other villages as are not locally producible.

In 1931 he declared, “A votary of Swadeshi will carefully study his environment and try to help his neighbors wherever possible by giving preference to local manufactures even if they are of an inferior grade or dearer in price than things manufactured elsewhere. He will try to remedy their defects, but will not give them up, because of their defects and take them to foreign manufactures.”

Gandhi explained that the concept of Swadeshi did not involve any ill feeling towards foreigners or other related narrow feelings. He wrote in 1923, “My definition of Swadeshi is well known. I must not serve my distant neighbor at the expense of the nearest. It is never vindictive or punitive. It is in no sense narrow, for I buy from every part of the world what is needed for my growth. I refuse to buy from anybody anything however nice or beautiful, if it interferes with my growth or injures those whom nature has made my first care. I buy useful healthy literature from every part of the world. I buy surgical instruments from England, pins and pencils from Austria, and watches from Switzerland. But I will not buy an inch of the finest cotton fabric from England or Japan, or any other part of the world, because it has injured and increasingly injures millions of inhabitants of India. I hold it to be sinful for me to refuse to buy the cloth spun and woven by the needy millions of India’s paupers and to buy foreign cloth although it may be superior in quality to the Indian hand-spun.”

In 1931 he warned, “But even Swadeshi like any other good thing can be ridden to death if it is made a fetish. That is a danger that must be guarded against. To reject foreign manufactures merely because they are foreign and to go on wasting national time and money to promote manufactures in one’s country for which it is not suited, would be criminal folly and a negation of the Swadeshi spirit. A true votary of Swadeshi will never harbour ill-will towards the foreigner; he will not be moved by antagonism towards anybody on earth. Swadeshism is not a cult of hatred. It is a doctrine of self-less service that has its roots in the purest ahimsa, i.e. love.”

Swadeshi should be used to support not the products of local mills but that of village industry. In 1926 Gandhi said clearly, “The test of Swadeshi is not the universality of the use of an article which goes under the name of Swadeshi, but the universality of participation in the production or manufacture of such an article. Thus, considered mill-made cloth is Swadeshi only in a restricted sense. For in its manufacture only an infinitesimal number of India’s millions can take part. But in the manufacture of Khaddar, millions can take part.”

He also emphasised the voluntary aspect of Swadeshi, “It is believed by some that Swadeshi could be affected by an embargo on foreign imports after the attainment of Swaraj. But that Swadeshi will be no Swadeshi. It will be a virtue practiced under compulsion. True Swadeshi is the invulnerable bulwark of the nation and it can only be said to be accomplished if it is practiced as a national duty.”

Gandhi was very clear that the progress of Swadeshi and Khadi should continue after the end of foreign rule, as these are equally relevant to post-independent India. He wrote in 1947, the year of India’s independence, “We were trying through khadi to place man above the machine, rather than allow the machinery driven by electricity or steam, to be the master. We were endeavouring through khadi to establish equality between man and man in place of the enormous inequality now existing between the poor and the rich, between the high and the low, between the man and the woman. We also endeavoured to make the labourer independent of the capitalist instead of the capitalist exploiting labour and assuming undue prestige. If, therefore, what we did in India during the last thirty years was not wrong, we should now carry on the programme of the spinning wheel, with all its allied activities with more understanding of all the implications and with greater vigour.”

As cloth is the most important industrial product, particularly in villages, village level self-reliant production would have established a firm basis for other village-based cottage-scale industries such as leather and footwear, but this path of development was by and large neglected in post-independence India. Although the government continued to give some support to khadi and village industries, an effort supported by several Gandhian organisations, nevertheless the production of most of the cloth has remained with the powerlooms and mills or powerlooms linked to mills. Handloom weavers suffer from many-sided problems, their most frequently voiced grievance is that of the non-availability of yarn at a fair price. The reason is that most handlooms get their yarn not from numerous charkha spinners, as Gandhi desired, but from mills. Hence the handloom as it exists today remains dependent on mills to a large extent. In order to increase their profits, mills frequently re-reel hank yarn (meant for handlooms and free of excise duty) into cones and divert it to powerlooms. Due to shortage of yarn and other factors, mass distress among weavers has been reported from several places.

Thus, ignoring the potential for village-based cottage-scale production has brought unemployment, under-employment and poverty to several million families, a tragedy that could have been avoided by making adequate use of existing skills of weaving, spinning and related works in villages.

As recently as 1993, Nandini Joshi, who has a doctorate in Economics, from Harvard, wrote a book in Gujarati (which has also been translated in Hindi) titled ‘Our Distress and Alternatives’ which argued that khadi and the spinning wheel are still practical and economically viable if only we give them a fair chance. An additional argument she advances is that khadi can help us to recover several hundred thousand hectares of land as badly needed fertile land for growing food. The mills require long and medium staple cotton which need more fertile land, irrigation and chemicals. On the other hand, short-staple cotton needed for the charkha can be obtained on less fertile land some of which is not under cultivation at present and there is no need for agri-chemicals.

The potential of strengthening food processing at village level in the form of cottage and small-scale units led by women is even stronger. Ignoring these possibilities of strengthening rural livelihoods, in the phase of neo-liberalisation the government moved away from Swadeshi and Gandhian thinking at a fast pace and this trend has accelerated further under the crony capitalism of the current ruling regime. Hence the country of Gandhi is moving away more and more from the spirit of Swadeshi. However, there is no doubt that the country and the world still need these valuable ideas perhaps even more than ever before.

*The writer is a journalist and author. His recent books include Man Over Machine (Gandhian Ideas for Our Times), and When the Two Streams Met (Freedom Movement), Vitasta, Delhi.

Other articles by Bharat Dogra:

Hindi literature and journalism will always remember the rich contributions of Manglesh Dabral

Why inter-faith harmony is today more important than ever before

Scrapping of Five-Year Plans was a bad idea