Excerpts from the “independent and non-sponsored” report, “A New Agenda for the Education Of Indian Muslims in the 21st Century”, by John Kurrien, PhD:

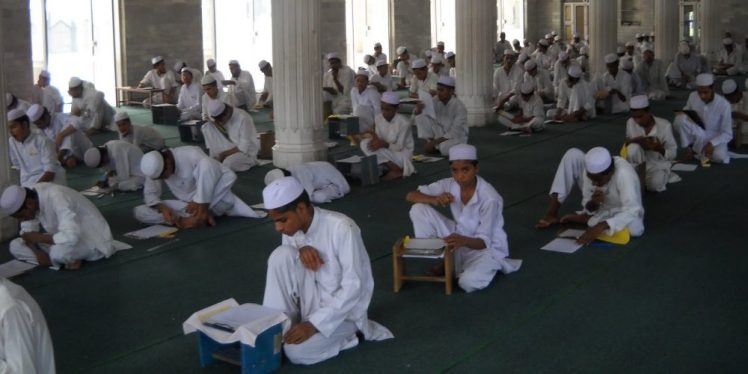

No discussion on the education of Muslims in contemporary India can be complete without discussing the role of madrasas. A significant contribution of the 2006 Sachar Committee Report was its frank and illuminating discussion on the role of madrasas in the education of Muslims in India. The main issues that it dealt with and the solutions that it articulated are still relevant to any discussion on their role in a new education agenda for Indian Muslims.

Beginning with the Committee’s articulation of the significant position of madrasas in the life of Indian Muslims, and the suspicion that madrasas evoked, are concerns that continue to resonate a decade later after its Report’s publication:

“Madarsas, through which the Community ensures that its future generations aquire knowledge of Islam, have become a symbol of Muslim identity in India- – – Labeling of Madarsas as a den for terrorists is extremely worrisome for the Muslim community. Even though there has been no evidence to suggest that Madarsas are producing terrorists they are constantly under scrutiny. It has been pointed out that the existence of Madarsas (though not as a substitute for regular schools) is necessary for Muslims as, apart from providing basic education, they serve as an important instrument of identity maintenance for the Community”.

Prior to the publication of the Sachar Report, there was a growing controversy about the number of madrasas – estimates varied from a few thousand to sixty thousand. One of the major contributions of the Sachar Committee was to provide a corrective to the popular myths about the number of Muslims attending madrasas – “a persistent belief nurtured, in the absence of statistical data and evidence, is that Muslim parents have a preference for religious education leading to dependence on Madarsas”

In this connection, an important contribution of the Sachar Committee report to the madrasa debate was to highlight the distinction between maktabs and madrasas noting that the former are neighbourhood schools, often attached to mosques, that provide religious education to children who attend regular schools to get ‘mainstream’ education.

It noted that the common belief that a high proportion of Muslim children study in madrasas stems from the fact that they are actually enrolled in the local maktabs, and that only 4% of all Muslim school-going children attended madrasas. The latest official DISE data indicates that recognised and unrecognised madrasas had a total enrolment of about 25.5 lakh students which constituted about 7.7% of the total Muslim student enrolment of 3.3. crore in 2015-16.

The 2006 Sachar Committee Report and DISE 2015-16 data indicating that 4% and 7.7% of all Muslim school-going children attend madrasas are the best recent official estimates available. Since many private schools, including madrasas, are not included in official enrolment data, we may never be able to quantify accurately the number of children attending madrasas, and also distinguish them from those studying in part-time maktabs.

This is highlighted by a 2011-12 estimate of the National Monitoring Committee on Minorities’ Education indicating that 9.7% of Muslim children attend recognised and non-recognised madrasas. Though even official estimates vary, it is clear that the overwhelming majority of poor Muslim students receive their formal education in mainstream government, government aided and private schools.

Key Features of Madrasas in Contemporary India

Since their advent in India with the early Muslim rulers, madrasas have changed to face a number of challenges. The following features of contemporary madrasas are largely a result of developments and reforms undertaken in colonial and post-independence India:

- Since they offer free education and often free boarding facilities, as well as possible employment as imams and maulvis, most madrasa students belong to poor families. This was not the case in pre-colonial India, where upper class Muslims also attended madrasas, which was training for employment as scholars and administrators in the reigning dispensation. But this changed in colonial India as the madrasa links to employment in the state apparatus was broken.

- The changing socio-economic composition of madrasas, and other developments in colonial India, reversed the earlier emphasis on rational studies in favour of the study of the Hadith to eliminate syncretic tendencies in poor Muslims and transform them into pious, personally responsible Muslims. Contemporary madrasas continue to be caught in this perceived conflict between worldly knowledge and religious knowledge. This struggle is reflected in continuing debates over the religious and secular aims of madrasa education, the extent to which secular subjects should be incorporated in the curriculum, and also which of these subjects should be considered secular and appropriate for study.

- There are a wide variety of madrasas in contemporary India. Many are grouped under, or loosely associated, with different schools of thought, often ideologically hostile to each other, like the Deoband, Nadwatula, Ahi i Hadith and Barelvi schools. There is little or no connection between them – most follow their own syllabus and textbooks, and there is no uniformity even in the number of years required to obtain degrees or different levels of learning. Most madrasas teach up to the primary level or at the most to the secondary level.

- Suspicious of government funding, and reversing the precolonial trend of depending on state patronage, the financing of colonial madrasas began to solely depend on community funding. This lack of trust of government, and reliance on community funding continues in contemporary India.

- However not all madrasas have continued to refuse state financial assistance. Some states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Assam have constituted madrasa boards and have provided grants-in-aid to madrasas registered with them. In this growing number of registered madrasas, the curriculum include secular subjects and use state-prescribed or NCERT textbooks.

- Many more girls are now attending madrasas, including coeducational madrasas, despite the popular perception regarding Muslim parent’s hesitation in sending their girls to co-educational institutions”.

Post-independence madrasa reform /modernisation of madrasas

Like their colonial predecessors, new developments have made contemporary madrasas make changes mainly due to pressures from contending forces and groups from within the Muslim community to respond to the changing external environment. Broadly, the motivation to modernise madrasas can be characterised by two broad types of goals:

- Preparing the new generations of ulema to become more knowledgeable and socially aware community leaders.

- Improving the skills and knowledge of madrasa students required to cope with the challenges of education and employment in modern India.

The first major intervention of the Central Government was the MHRD scheme, Area Intensive and Madrasa Modernisation Programme of the Ministry, which focused on infrastructure and curriculum development and was implemented for a number of years. The Sachar Committee considered the scheme ineffective, and recommended that the scheme be reviewed, and revamped before embarking on its expansion.

While there have been some other government sponsored programmes, the next major intervention in the modernisation of madrasas was the MHRD centrally sponsored scheme, Scheme for Providing Quality Education in Madrasas (SPQEM). According to a 2018 NUEPA evaluation, SPQEM started during the XIth Five Year Plan in 2009-10 covered over 21,000 madrasas and was currently being implemented in 18 states in the country.

The two main objectives of the SPQEM are: a) to encourage Madarsas and Maktabs to introduce formal subjects i.e. Science, Mathematics, Social Studies, Hindi and English; b) to enable the children studying in Madarsas and Maktabs to achieve academic proficiency in classes I to XII.

This was to be achieved by providing for the following: salary of additional teachers, strengthening of libraries and book banks, providing teaching learning materials (TLMs) and other essential pedagogical equipment for teaching modern subjects at primary/middle/secondary and senior secondary levels.

While individual or some groups of private madrasas are also undergoing modernisation, it is the quality of the large-scale implementation of the SPQEM in many states of India which has the greatest relevance to understanding its role in the education of vulnerable Muslims in contemporary India. The following is based on the findings of a 2018 NUEPA evaluation report, and to a lesser extent an earlier 2013 evaluation conducted by the K. R. Narayanan Centre for Dalit and Minorities, Jamia Millia Islamia.

- The responses of the community, parents and madrasa staff and management were considerably enthusiastic about SPQEM because it combined religious and modern subjects thus serving both material and spiritual needs.

2. The positive impact of the scheme included improvements in the enrolment of poor children and madrasa infrastructure. It also provided madrasa students a new opportunity to study modern subjects and thus allowing students to aspire to “becoming doctors or engineers or civil servants or police officers”. - Under the SPQEM scheme, the extent and coverage varies from state to state. Most madrasas focus mainly on elementary education and the coverage of higher levels of education is limited.

- The 2013 evaluation observed that there was little clarity on SPQEM guidelines on eligibility of madrasas, which had resulted in a variety of implementation deficiencies. Among the more important consequences was the inclusion of ineligible institutions. Funded under SPQEM, many madrasas were being “run as essentially mainstream public schools” and in many others “the curriculum followed was hardly any different from that of any elementary school except one or two classes of Sunni theology each week.”

Limited Teaching of Secular Subjects Both the 2013 and 2018 SPQEM evaluations had documented that untrained and unqualified teachers were teaching subjects like science, mathematics and English, and that teachers were appointed by individual madrasa managements, and not regulated by any authority.

Moreover, in many government funded madrasas, the science kit and the single computer provided was also not used by students. Moreover both students and teachers were using the conventional rote methods of teaching and learning used in teaching the Quran and Islamic subjects for the secular subjects such as science and social studies.

The teaching of secular subjects in other unrecognised madrasas is likely to be even more limited, since it is government SPQEM funding that has enabled many madrasas to provide both the teachers and learning resources to teach secular subjects. A 2015 report of a survey of 55 madrasas conducted in by Karnataka Students’ Islamic Organisation of India (SIOI) documented that less than half taught English, and less than 20% had access to science, mathematics and social science subjects. Another study of 500 prominent madrassas across India revealed that 85 per cent of them did not teach Social Science, English and Mathematics to the students.

The Sachar Committee had recommended that mechanisms needed to be worked out to link madrasas with mainstream education and employment in 3 ways: madrasas could be connected to higher secondary boards so that madrasa students could shift to mainstream schools after completing madrasas; provision of “equivalence” to Madarsa certificates/degrees for subsequent admissions into institutions of higher level of education, especially when admission is done through a common entrance examinations; similar recognition of madrasa degrees to enable them to sit for competitive examinations for Civil Services, Banks and Defence Services.

There is no evaluation of the extent to which these mechanisms have been implemented, and have enabled madrasa students to access higher levels of education and employment. The 2018 NUEPA evaluation indicated that only a small number of students used the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) scheme to enable madrasa students to study at the secondary and upper secondary level, mainly due to lack of awareness of this facility. However, despite any formal recognition of madrasa qualifications, transitioning from a madrasa to a mainstream institution at any stage of school or college education will pose adjustment and academic problems.

As Arshad Alam has noted that when students transition from the parallel stream of primary-level madrasas to continue their education in regular schools, they “will find it very hard to adjust to new educational and pedagogical context”. This can become perhaps impossible for most madrasa students to cope with when they transition later at high school or higher education stages.

The language of classroom instruction can facilitate or limit entry into higher levels of school and college education. Like many other aspects of madrasa education in India, there is no empirical data available on the medium of instruction in these institutions. In 2002, Imtiaz Ahmad impressionistically observed that Urdu was the medium of instruction in North Indian madrasas.

It is unclear how many madrasas continue to teach in Urdu in the northern and other states of India. However, the educational mobility of Urdu medium students is blocked, as few high school and higher secondary schools use it the language of instruction, and even more limited is its use in higher education.

Imtiaz Ahmad also noted that in Bengal, Assam, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, the medium of instruction was the regional languages. Madrasas registered under SPQEM are likely to be using the regional language, but the extent to which the regional language is used as a medium of instruction in madrasas is also likely to vary from state to state, and even and within states.

In Karnataka, the Students Islamic Organisation of India (SIOI) study of 55 madrasas indicated that more than 50% did not offer Kannada as a subject. Moreover, the study of Koran and related religious subjects in most madrasas would be in Arabic.

Therefore, even if government increasingly facilitates the recognition of madrasa degrees for entry into higher levels of school or higher education, many madrasa students immersed in religious instruction and secular subjects in other languages like Arabic and Urdu would find it far more difficult than regular students to cope with academic requirements when they transition to mainstream educational institutions.

There is only limited evidence, and no state or all-India level studies available, exploring the link between madrasas and employment. A study of 77 madrasas in Mewat district of Haryana, a Muslim majority district, enrolling about 8,000 poor Meo students indicated that 78% of the madrasa graduates were employed in madrasas, dargahs and mosques, and only a few went on to university education.

The study noted that only around three per cent of madrasa educated persons have attained a higher level of socio-economic development. Otherwise “most of them fell into the category of poor 58 socio-economic conditions as madarsa trained persons cannot bring any substantial socio-economic change because their professions cannot bring good remuneration”.

Confirming the popular perception that most madrasa graduates are mainly absorbed in low-paying jobs, and that their education restrict them from other forms of employment and social mobility, another observer of madrasa education in Karnataka has trenchantly articulated varied aspects of the negative impact of madras education on their graduates.

The evaluations of the SPQEM indicate that poor Muslim parents overwhelmingly support the SPQEM initiative primarily because it combines secular subjects with religious knowledge. This is also an important factor in sending girls to madrasas – there are more girls than boys in them. This imbalance is a direct consequence of the gendered world view of poor parents which privileges the main goal of school education as preparation of daughters to be good Muslim wives and mothers. However, while clearly the introduction of secular subjects in madrasas is absolutely critical in contemporary India, and is welcomed by poor Muslim communities they serve, the implementation of the SPQEM scheme is extremely deficient and needs to be reviewed thoroughly before expanding it.

Recruiting additional untrained and unqualified teachers by Madrasa Committees, and formally adding secular subjects and some resources -a single computer, a science kit which have rarely been used, and an arbitrary selection of library books – will not significantly improve the quality of teaching and learning in government funded madrasas.

The present Minister of Minority Affairs, Muktar Abbhas Naqvi has recently reaffirmed the present BJP Government’s commitment to modernise madrasas which included the training of teachers in secular subjects to connect their students to mainstream avenues of education. However, the mainstreaming of Indian madrasas requires large-scale qualitative and quantitative changes. There is no political will or public support for the quantum jump in financial and human resources that will be required to properly modernise madrasas in India, where Muslims are a disadvantaged minority.

Moreover, many community funded madrasas would stay away from such a scheme, and would oppose any possible large- scale government attempt to control what is taught in madrasas, viewing it as an unwarranted intrusion in their affairs.

Consequently, for the various reasons that have been already detailed, SPQEM and other such government schemes for modernising madrasas cannot be quantitatively expanded and improved to become an important parallel avenue for providing 12 years of quality education for poor and lower middle class Muslims, and provide them with the literacy, numeracy and critical thinking skills required to meet the challenges of 21st Century India.

—

Read full report HERE

Courtesy: Counter View