The massive eviction drives at Silsako in Guwahati, the capital city of Assam, in February-March this year, continue to haunt the people who watched the bulldozers tear down their or their loved ones’ houses. For the past four months, many evictees have been camping at the site, demanding compensation and rehabilitation. Some of those who lost their homes and hearths have managed to arrange rented rooms, while others still stay at the site, sheltered under tents, amidst the torrents of the monsoon rain in Assam.

Silsako, a natural lake (Beel in Assamese) located in Guwahati, plays a crucial role in the city’s water system. However, the discourse around the lake has transcended its physical boundaries and become an assemblage of several issues. These encompass human rights, ecological restoration of the city, flood mitigation, and the rights of the indigenous people. Let us explore how Silsako has evolved into a contentious space.

SILSAKO EVICTIONS

The eviction drives at Silsako Beel are not new; in fact, they can be traced back to 2008-2010 – during former CM Tarun Gogoi’s term. However, the earlier drives were not as massive as the recent ones, where nearly 600 houses have been demolished.

We can trace the series of recent eviction drives back a year to May 13, 2022. Approximately 100 homes were demolished by the Guwahati Municipal Development Authority (GMDA) then. The locals claim that they received no prior notice, and most affected families have been homeless ever since. Then, an unprecedented and massive drive took place between February 27 and March 2 this year. “During those four days, over 500 houses were reduced to rubble,” said Naina Begum, a resident of the area.

The Gauhati High Court had stayed the eviction drive against 10 petitioners, who had residential houses in Silsako Beel, but only till March 3, 2023.

NewsClick visited the areas near Silsako Beel in June. Upon seeing the site, it was impossible to imagine that there had once been a bustling colony with many families. The entire patch of land appeared desolate and barren.

The sites where the evictees’ houses stood before March 2023.

At the site, one can also see a huge pond, which, according to the locals, was dug by the administration between 2021 and 2023. Jyoti Xan, Ibrahim Ali, Abedur, and Sankar Das among others who have been residing in the area for a long time, informed NewsClick, “This was previously a grazing field and is far from the houses that were demolished. The pond is the intended location for the much-hyped water park.”

The pond dug by the GMDA.

In addition to those who lost their homes during the evictions, some locals in the area, fearing further evictions, have been staging a protest at the site. It has been four months since people started camping here in protest, and a few meters away, another tented camp can be seen, with police and intelligence bureau personnel keeping watch.

THE QUESTION OF LAND RIGHTS

The government claims that clearing the lake of encroachers is necessary for ecological restoration and to address Guwahati’s artificial flood issues under the ‘Mission Flood Free Guwahati’ However, the evictees and those who fear further evictions argue that they should not be solely blamed for both the ecological devastation and the floods.

The Beel is connected to channels that bring water to it and channels that carry water to the Brahmaputra River.

The conflict arose from the enactment of the Guwahati Water Bodies (Preservation and Conservation) Act of 2008, with an amendment in 2010. Silsako Beel came under the jurisdiction of the act as a wetland to be protected. However, questions arise regarding the boundaries of the protected area of the wetland and the rehabilitation of the people uprooted from their homes.

Naina Begum, a resident of the Borbari area near Silsako, has emerged as one of the prominent voices in the protest camp. Speaking with NewsClick, Naina said that her family settled in the area between 2007 and 2008, and she currently resides there with her husband and family. She mentioned, “Our plot of land was purchased by my uncle from my grandparent. When I first arrived here, I was quite young. We used to see paddy fields, but I cannot recall ever witnessing a flood.”

When asked about the presence of people before 2008—when the act was introduced—Naina confirmed that there were indeed people residing in the area. However, she added, the settlement began to grow significantly after 2006.

Interestingly, the houses that were demolished this year had holding numbers provided by the Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC) and electricity connections. Naina questioned, “How could the GMC provide holding numbers if these houses were located in protected areas?” She informed NewsClick that the electricity connections and holding numbers were assigned in 2010-11. Another crucial point highlighted by Naina and others is that the Public Works Department (PWD) constructed roads in the area as recently as 2019. Naina asked further, “If they intended to destroy these houses, then what was the purpose of these developments?”

Ibrahim Ali, who claims to have been residing in the area for a significant period, witnessed the demolition of his house during this year’s eviction drive. “Back in 2007, some of us who were living here approached the Deputy Commissioner, urging that our land should also be granted ‘myadi patta’ (official land ownership). We have seen wealthy individuals receiving such titles for government-owned land. Unfortunately, our request was not fulfilled. While we remained as settlers, the privileged ones were granted the ‘myadi patta’,” he alleged.

Ali also informed NewsClick about the paddy cultivation activities that many of them were involved in. However, these practices came to a halt around 2013.

NewsClick also spoke to Upamanyu Hazarika, a Supreme Court lawyer and convenor of the Prabrajan Virodhi Manch (PVM). Hazarika raised some critical questions regarding the eviction drive and the lack of clear demarcation for the boundary of the protected wetland. He argued that the eviction drive exhibited discrimination against the indigenous people, as those affected possessed holding numbers, electricity connections, and had access to roads; yet, they did not receive prior notice. Hazarika questioned, “Is this not a flagrant violation of people’s rights?”

Furthermore, he highlighted the case of Jayanta Malla Baruah, a Cabinet minister of Assam, who had constructed his house along the Beel stretch. “When did he buy the land and when did it get myadi? Was it before 2008? Remember Baruah became an MLA after 2009,” he said. [Jayanta Malla Baruah won his first Legislative Assembly seat in 2011.]

Akash Doley is a member of the Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti (KMSS) and an active participant in the Silsako protest camp since its inception. According to him, “We have the document of paying ‘khajna’ (land revenue tax) by Mohuwa Mikir as early as 1971. His descendants are still here. Actually, what happened is people like Mohuwa Mikir came early and then occupied lands and thereafter they sold it off in pieces. There was another named Asgar Ali who did the same. These are indigenous people and now they are facing troubles.”

Doley said that on July 16, 2021, during the first Assembly session after Himanta Biswa Sarma became the chief minister of Assam, he had said that [documents for] people’s rights on land will be provided. This was after the finance minister announced evictions for the protection of wetlands. “Sarma must have said what he said keeping in mind the GMC election in 2022,” he suggested.

Akash informed NewsClick that the residents of the area used to vote in the Dispur Assembly constituency. “During the campaign for the GMC election, Sarma had also spoken about finding a solution to the issue while interacting with one of the residents here,” he claimed.

THE ANATOMY AND HISTORY OF SILSAKO BEEL

Where is the Silsako Beel located, and what ecological importance does it hold? How does it contribute to Guwahati’s flood situation? Has the Beel been encroached upon and polluted? The answer is yes, there was indeed a Beel, but its history reveals a specific geography and a legacy of human interference.

According to Professor Sarat Phukan, Department of Geology, Gauhati University, a PhD thesis written by Memma Singh compiles extensive research on the Silsako Beel.

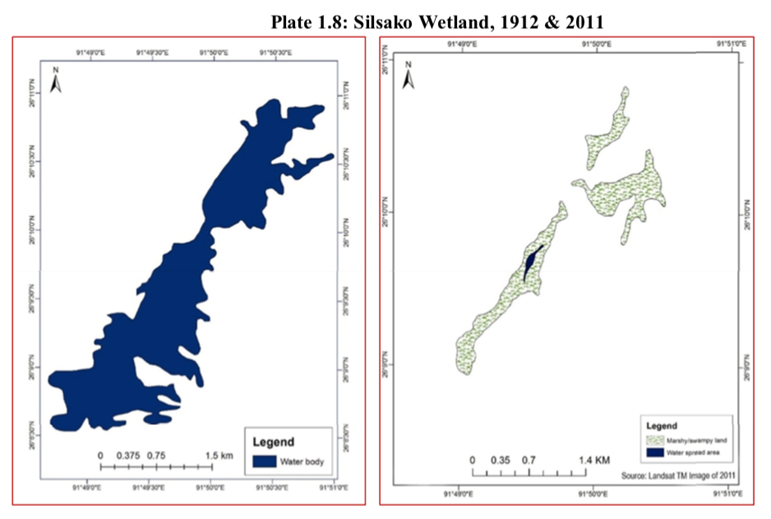

Contrary to the common perception and typical characteristics of natural lakes, the Silsako Beel exhibits an elongated geography – as revealed in the maps presented in Singh’s research.

The Silsako Beel:1912 vs 2011. Image credit: Memma Singh.

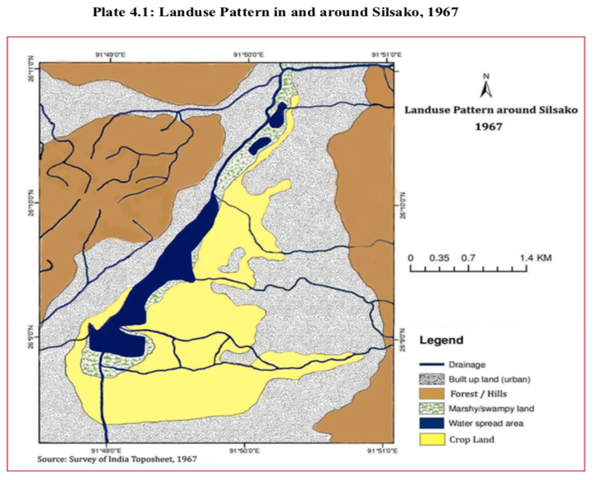

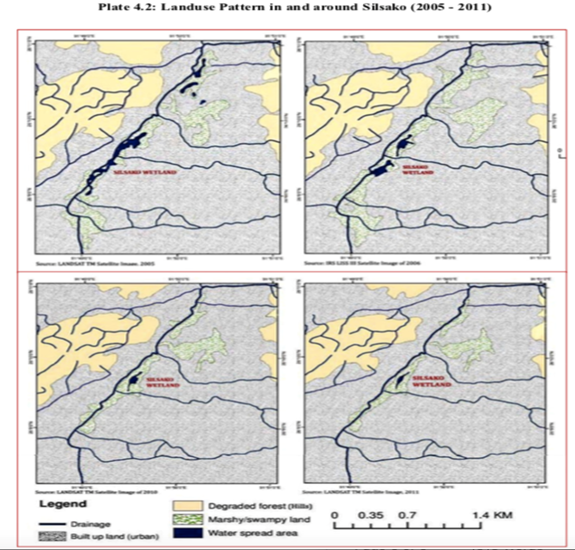

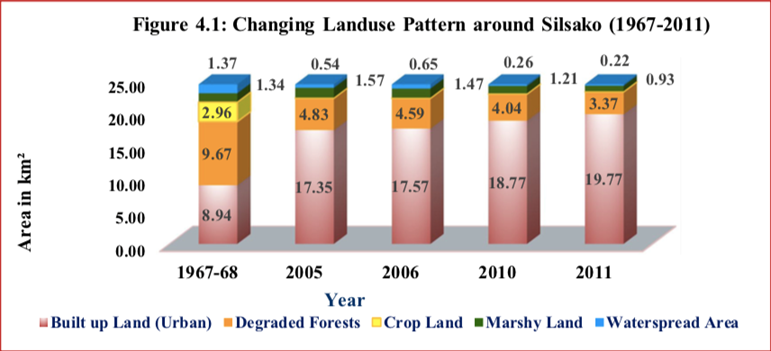

Over time, the wetland has experienced changes in land use patterns, and it is evident that urban growth has exerted pressure on the Beel.

The images above present a compelling narrative about the wetland, highlighting a significant increase in built-up land area that occurred predominantly before 2005. These images also corroborate the accounts of local residents regarding the practice of paddy cultivation. This raises the question of whether there was a sudden surge of interventions at the wetland prior to the year 2000.

A few elderly locals told NewsClick that the area had served as the main waste dumping ground for Guwahati city, possibly before 2000. Some even mentioned an announcement during the tenure of the Prafulla Mahanta-led government (around 1996) about a stadium at the site, although this claim could not be verified. Nonetheless, waste dumping emerged as a significant issue during that period.

Partha Das, head of the Water, Climate, and Hazard Division of Aranyak, a leading environmental and scientific research organisation based in Guwahati, said, “The dumping issue in and around Silsako became a serious issue and posed a threat to the wetland. We campaigned elaborately on the issue, and later the dumping was shifted to Boragaon-Gorchuk area near the Deepor Beel (another important wetland in Guwahati).”

Das further stated, “The Beel has to be restored to its near-natural condition if we expect its biological productivity to be retained. The Beel supports a wide range of biodiversity.”

He added, “Making it a clear body may have implications for flood mitigation, but the challenge is to restore it to its natural wetland form along with the hydrological channels linked to it, which carry a huge volume of stormwater coming down from the nearby hills, including those of Meghalaya. Additionally, the feeder channel ‘Bondajan’ also needs to be revived, and timely cleaning of the channels is pertinent to mitigating artificial floods in the city.”

The Silsako Beel encompasses multiple inlet and outlet hydrological channels. The inlets play a vital role in recharging its water, while the outlets are responsible for carrying away any excess water. The primary outlet, known as the ‘Bondajan,’ meets the Brahmaputra River, facilitating the discharge of the surplus water.

The degradation of this significant wetland and the resulting loss of its rich biodiversity can be attributed to a lack of long-term vision and government planning. Earlier reports highlighting the deterioration of the Beel raised concerns about its environmental condition. However, it is the people belonging to lower socio-economic strata who ultimately bear the brunt of the government’s long-term apathy followed by drastic and arguably destructive measures.

One of the issues central to the recent developments has been the inconsistency in the demarcation of the wetland’s boundaries. The Guwahati Master Plan 2025 says that the Silsako basin covers 6,534 hectares. The early reports say that 440 bighas of land were notified to be under Silsako Beel. However, the action plan for Silsako Beel produced by the Pollution Control Board, Assam (PCBA) stated: “Silsako Beel is spread over an area of 1,000 Bighas of land as per the revenue records. The notified area of Silsako Beel as per the Guwahati Waterbodies (Preservation and Conservation) Act 2008 has been mapped in Geographical Information Systems (GIS) by GMDA and ASTEC. The report was submitted to GDD, DC (Kamrup) (Metro) in July 2015. As per the report, there is no existing physical demarcation of the water body and it is encroached at several stretches.”

The Assam Gazette notifies the Guwahati Waterbodies (Preservation & Conservation) Act, 2008.

According to recent reports, the notified area for the Silsako wetland is approximately 1,800 bighas, out of which 1,200 bighas are currently “under encroachment”. The reports also indicate that during the eviction drives, 100 metres on each side of the water channel (Bondjan) were cleared. However, locals have contradicted these claims, stating that more than 100 metres of land on each side of the channel were actually vacated in the latest eviction drives.

BIGWIGS GET A PASS?

Suprakash Talukdar, state general secretary of the CPI(M), told NewsClick, “The Beel issue is quite complicated and old. There should have been proper planning instead of sudden massive eviction drives targeting people with limited incomes. Why could the government not formulate a housing plan beforehand? They have given lands in Assam to the likes of Baba Ramdev. How can one fully trust that the freed land won’t be handed over to big corporates?”

Bibek Das, state general secretary of CPI(ML), pointed out that Himanta Biswa Sarma held a prominent position as the minister of GMDA in the Tarun Gogoi-led government. “He had significant power and nothing could be done without his consent. So, how is it possible that he did not pay any attention to the Beel, especially after the implementation of the preservation act of 2008? Furthermore, he promised to provide land ownership certificates to the people before the election. Now, the evicted individuals are left to fend for themselves.”

According to Das, people in the state Assam still await proper compensation for the lands they lost during highway expansions. “How can we believe that he will provide settlement to the evictees?” he asked.

Bidyut Saikia, general secretary of the KMSS, who has been in the Silsako protest camp for the last three months, asked why the buildings of Himatsingka and the business ventures of Badaruddin Ajmal are spared in the evictions. He stated, “The Himatsingka building (Ideal Hill View) is a 17-storey residential complex and if you see the site, then you will find it stands just at the bank of the channel (Bondajan). The Bondajan is filled by 250 metres to reach the house of minister Jayanta Malla Baruah. Does the government want to say that the ordinary people are a threat to the wetland, but not the bigwigs?”

“Actually, this government is not interested in the indigenous people of Assam, rather they are good friends of the big corporate lobbies, and we fear that the cleared land will be handed over to such lobbies,” he said.

The Silsako evictions, along with the speculations over government plans, raise more questions than answers – questions that cannot be easily dismissed.

Courtesy: Newsclick