Excerpts from Oxfam report “Addressing the Human Cost of Assam Tea: An agenda for change to respect, protect and fulfil human rights on Assam tea plantations”:

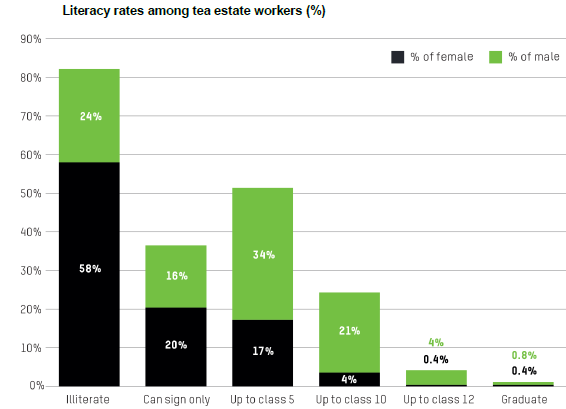

Assam’s women tea workers are doubly marginalized – firstly as isolated and unassimilated descendants of migrant labourers, and secondly as women. Oxfam’s experience suggests that traditionally people with low incomes in India prioritize boys over girls when allocating limited resources for education, healthcare and nutrition. For example, the research commissioned by Oxfam found that around 78% of female tea workers are either illiterate or can only sign their names to collect their wages (compared to around 40% of male workers). Researchers also found a correlation between workers’ level of education and gender.

It is predominantly women who carry out the labour-intensive job of harvesting tea. This is because women’s hands are perceived as being better suited to plucking the delicate tea leaves for processing. Yet the concentration of women in these low-paid jobs; their low levels of literacy, education and union representation; and their high levels of dependence on employers are strong markers of gender discrimination.

Work in the factories – which is better paid, has better facilities and is regarded as more dignified and prestigious – is done predominantly by men, although women workers interviewed during the research asserted that they are just as capable as men of doing factory work.

There is little room for rest or recreation during the gruelling daily routine at work and at home (see Box 6). Including the unpaid domestic work women do, by the time they go to bed (usually for a maximum of six hours) they have done around 13 hours of physical work, including plucking and carrying up to 30kg of tea leaves. This is sometimes while carrying a baby on their back, and often in temperatures of up to 38 degrees or in torrential monsoon rain.

A typical day for a woman tea worker in Assam

- 4am–4:30am: Wake up and clean the house and courtyard (some also need to collect water)

- 5am–6am: Prepare food for the day

- 6am–7am: Get ready and leave for work, walking 8–9km to reach the plot

- 8am–4pm: Work in the garden (if even one minute late she could lose an entire day’s wages)

- 4pm–5pm: Weigh the plucked leaves (assuming manager arrives on time – if not, much later), sometimes collect firewood on way home

- 5pm–8pm: Home, freshen up and prepare dinner

- 8pm–9pm: Eat dinner

- 10pm: Go to bed

Source: Based on actual and average figures and times provided in: TISS. (2019). Decent Work for Tea Plantation Workers in Assam: Constraints, challenges and prospects.

Facilities such as canteens and toilets (which are generally available in the factories, where workers are predominantly men) are lacking in the fields, which is where women mainly work. Researchers learned that because of the presence of mostly male ‘sardars’ (supervisors), women try to find privacy to relieve themselves, moving far away from where their colleagues are working; however, this makes them vulnerable to sexual abuse or attacks by wild animals.

The lack of hygiene facilities in the fields, as well as water shortages at home (for washing menstrual cloths), pose health hazards for women. As a result, many stay at home when menstruating, thus losing out on earnings.

The pressure on women workers in the tea industry continues throughout pregnancy and motherhood. A 2016 fact-finding mission in West Bengal and Assam by the Global Network for the Right to Food and Nutrition found that women are not given lighter tasks during pregnancy, and while most return to work a month after delivery, some workers reported being put to work the very next day after giving birth. Temporary workers do not receive any maternity benefits.

Anaemia is a leading contributor to maternal deaths in Assam’s tea estates, with 363 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017 – compared with 174 for the rest of India.61 Indeed, according to the British Medical Journal ‘Assam has almost double the national average maternal mortality rate’.62 Yet Oxfam-commissioned research found that pregnant women were missing out on regular health checks because the roads to health centres and hospitals were in such poor condition, which also makes it difficult for ambulances to reach women (they can take a whole day to arrive).

The lack of childcare facilities means that mothers of newborns often work with them strapped to their body – or leave them at home in the care of older children. One woman worker explained that ‘most of the elder girls have to stay at home and manage the [house] work if their mother is a permanent worker in the garden’ and that dropping out of school at the age of 12 is therefore common. This perpetuates the vicious circle of under-education, exploitation and lack of capacity to stand up for their rights.

Another issue that emerged during the research is that domestic violence against women tea workers is common. This is within the context of wider Indian cultural norms that traditionally sanction violence by men to control women and girls, and where gender norms reinforce inequality and lack of women’s agency.

As well as physical violence, one woman worker told researchers how ‘the psychological stress borne by the pluckers is very high inside the gardens’ too. Both this and domestic violence could be an underlying symptom of alcohol abuse, which is common and cuts further into workers’ meagre wages.

As media enquiries have revealed,64 the poverty and hardship of life as a woman worker on Assam’s tea plantations have driven some young women and girls to seek a better life elsewhere. However, they can find themselves in even worse situations, trapped by traffickers in domestic or sexual slavery.

These are some of the many insidious ways in which women workers on Assam’s tea estates are exploited, marginalized, disempowered, abused and ignored. Any attempt to bring about improvements in the lives and working conditions of Assam’s tea workers must therefore begin with addressing the specific challenges and vulnerabilities facing women workers.

—

Click HERE to download the report

Courtesy: https://counterview.org/