The quasi-judicial Foreigners’ Tribunals (FTs) in Assam –legitimised by the Foreigners Order of 1946 and thereafter 1964– have become routine instruments of exclusion by disregarding due process and constitutional safeguards, a comprehensive study of these tribunals and the broader legal crisis of India’s citizenship adjudication has revealed. The latest report by the Bengaluru-based National Law School of India University (NLSIU) and the Queen Mary University of London, to be formally released on Sunday (July 27, 2025), called for an urgent, fundamental rethinking of the legal structures governing citizenship in India given the possibility of an Assam-like exercise to update the National Register of Citizens (NRC) across the country.

The report, titled ‘Unmaking Citizens: The Architecture of Rights Violations and Exclusion in India’s Citizenship Trials’, the report has been authored by Mohsin Alam Bhat of Queen Mary University, Arushi Gupta, and Shardul Gopujkar, with the support of researchers and law students from the NLSIU, and members of Parichay Legal Aid Clinic. The event took place at the Teen Murti Bhavan, Teen Murti Marg, New Delhi.

“As of 2025, Assam’s tribunals have declared nearly 166,000 people as ‘foreigners’. In addition to more than 85,000 pending cases, these tribunals may also soon hear more than a million appeals from those excluded from the NRC,” one of the speakers said at the release.

Among the speakers at the release were Hon’ble Mr Justice Madan Lokur (Retired), former Judge, Supreme Court of India, Dr. Usha Ramanathan, Human Rights Activist and Independent Researcher, Mr. HRA Choudhary, Senior Advocate, Gauhati High Court, Dr. Mohsin Alam Bhat, Assistant Professor of Law, Queen Mary University of London and Ms. Darshana Mitra, Assistant Professor of Law and Director-Clinics, NLSIU.

In 2020, in the Statelessness & Citizenship Review, a paper by Talha Abdul Rahman[1] titled, Identifying the Outsider: An Assessment of Foreigner Tribunals in the Indian State of Assam, also interrogates the constitutional validity of the very institution of Foreigners Tribunals in Assam.

What the report says

The analysis, based on 1,193 High Court cases, landmark Supreme Court rulings, and in-depth field interviews, this report offers the most comprehensive study yet of Assam’s Foreigners Tribunals. It reveals a legal system in deep crisis: over 165,000 people have already been declared “foreigners,” with 85,000+ cases pending and more than 1 million NRC appeals potentially headed to these opaque tribunals. The report documents widespread arbitrariness in decision-making, including the wholesale rejection of documentary and oral evidence, and the absence of legal norms to protect individuals from wrongful targeting. These are not isolated failures—they reflect an institutionalised machinery of exclusion, with severe regional and national implications, says a statement released by the NLSU.

“Citizenship adjudication engages constitutionally significant questions with profound consequences, including the risk of statelessness. Such determinations require bodies that are legally constituted, independent, impartial, and composed of competent legal officers,” the study summarises in a chapter on “institutionalised arbitrariness”.

The report argued that the FT system fails on all these counts. “It lacks a secure legal foundation, is vulnerable to executive interference, and is staffed by inadequately qualified adjudicators. It thus stands in stark violation of the rule of law and the right to an effective remedy under both domestic and international law,” it said, adding that the FTs have become routine instruments of exclusion and violate the right to a fair trial.

‘Lowering standards’

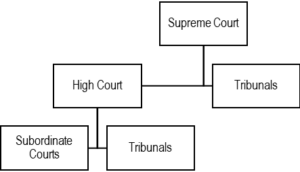

At present, Assam has 100 FTs, each headed by a judge-like member, which were formed after the Supreme Court scrapped the controversial Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act of 1983 in 2005. Of these 100 tribunals, 36 are permanent and 54 require periodic extension of terms from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). The Foreigners Tribunals, unlike Tribunals that have a constitutional validity (established under Part XIVA of the Constitution), specifically Articles 323A and 323B, which are under the higher judiciary, are solely appointed by the state executive. Tribunals that have a constitutional legitimacy were introduced by the 42nd Amendment in 1976. Article 323A deals with administrative tribunals, while Article 323B pertains to tribunals for other matters. Contrary to this, the sole adjudicator –in appointment and renumeration –is the state executive—in a sense blurring the constitutional scheme of separation of powers. [2]

Figure 1: Structure of Indian tribunal system

Source: PRS

NLSU Study: Assam’s Foreigner Tribunals

The study further highlights that the appointment process for Foreigner Tribunal (FT) members is opaque, with no guaranteed tenure. Advertisements by the Gauhati High Court and notifications from the Assam Government’s Political Department specify terms of one or two years, varying by executive whim, and extendable at the State’s discretion, it says.

“This tenure is governed by no legislation or by-laws and depends entirely on executive whim, despite being an essential legislative function. Moreover, it is violative of the Supreme Court’s judgments holding that a tenure of less than 5 years threatens to compromise the quality of adjudication by tribunals,” it said.

“The qualifications for FT members have progressively weakened. In 2011, only retired judicial officers from the Assam Judicial Service, experienced in procedural law, were eligible. They could serve until age 67, with salaries based on last drawn pay plus allowances. This ensured appointments of individuals with judicial expertise. By 2015, eligibility expanded to include advocates with at least 10 years of practice, lowering the standard,” the report said.

Appointments became two-year contracts with fixed monthly pay, enabling lawyers without judicial experience to decide critical citizenship matters. The 2019 revisions diluted requirements further; minimum practice dropped to seven years, minimum age to 35, and appointments became more flexible, allowing less experienced candidates to adjudicate complex citizenship issues, thereby compromising the quality of justice,” it stated.

A Gauhati High Court notification added criteria of “fair knowledge of the official language of Assam” and “Assam’s historical background giving rise to foreigners’ issues.” Yet, no requirement exists for expertise in immigration or citizenship law, the report pointed out.

The authors noted with concern that citizenship determination under the FTs has remained unchanged even after Parliament enacted the Immigration and Foreigners Act of 2025. “The stakes for legal violations have become unprecedented, with the prospects of a nationwide NRC exercise and the recent spree of ‘pushback’ deportations in Assam,” they said, calling for an overhaul of the legal structures governing citizenship in India.

[1] Talha Abdul Rahman (BA, LLB (Hons) (NALSAR, India), BCL (Oxon), Advocate on Record, Supreme Court of India, New Delhi. Visiting Fellow (2020), Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne. The author acknowledges that this work has immensely benefited from the Visiting Fellowship and support from Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne.

[2] The tribunal system has developed as a parallel to the traditional court system over the last eighty years. The Income Tax Appellate Tribunal was created in 1941 to reduce pendency of cases in courts.1 After the insertion of Articles 323A and 323B, several tribunals such as the Central Administrative Tribunal as well as sector specific tribunals were set up from the 1980s to 2010s. The Finance Act, 2017 consolidated several tribunals. In 2021, a Bill has been introduced that abolishes nine tribunals and transfers the matters to courts.

Related

Foreigners’ Tribunals: Why were they established and how do they operate?

EXCLUSIVE: Foreigners’ Tribunal notices pasted on electricity poles in Assam!

Proceedings before Foreigners’ Tribunals are really the issue: Teesta Setalvad