‘All of Muslim society will have to explain this silence’

The Shiv Sena party organs, Saamna and Dopahar ka Saamna in a series of rabid writings in early October were used by the ruling to foment communal passion not only against M.F. Husain, but all Muslims and Islam.

The first unsigned article, entitled Halkat Husain (Shameless Husain) that appeared on October 6, 1996 had this blurb in bold print:

“Maqbool Fida Husain, by depicting Hindu Gods and Goddesses naked has displayed his innate Muslim fanaticism. But if he had any guts at all he should have painted the Prophet of Islam copulating with a pig. Then his co-religionists would have cut him to pieces and thrown his body away.”

Several groups of Muslims from Mumbai protested against this piece of provocative writing and even filed cases against the offending publication. But, ironically, no case was filed against its editor-in-chief and SS supremo, Bal Thackeray.

We reproduce excerpts from two such articles where Husain’s alleged misdemeanours are magnified and hysteria is sought to be built against him because of the fact of his having been born a Muslim and bearing a Muslim name.

(The first, an unsigned article was published in ‘Dopahar ka Saamna’ on October 6, 1996):

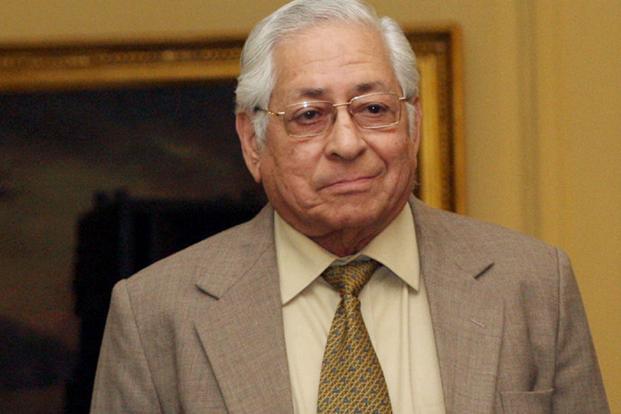

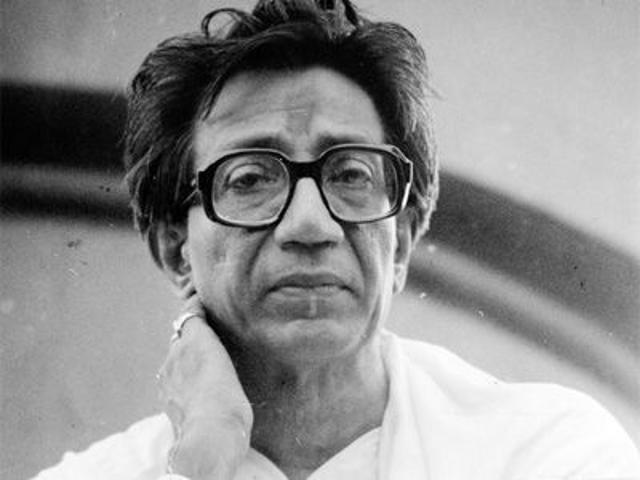

Maqbool Fida Husain is the contemporary world’s most well-known and successful painter. In India and abroad, he is a much sought after name. In London and America his paintings sell for Rs. 20 lakh.

For the wealthy neo-rich, buying a Husain painting and displaying it in their drawing room is the height of fashion. These members of the neo-rich have neither an understanding of art nor the critical abilities or discretion to recognize a painter. They buy a painting simply because it is a Husain. Just like drinking Coca Cola instead of Pepsi.

The truth however is that Maqbool Fida Hussein is a petty and trashy painter with a sick mind…

Some years ago, Husain had depicted portions of the Mahabharata in his paintings. Among these was a painting of Draupadi. The Draupadi that he painted was without any clothes. Completely naked. When in the Mahabharata, Draupadi, despite the relentless efforts of Dushasana and Duryodhana, never stood without her clothes because Lord Krishna had taken it upon himself to protect her modesty. The Lord made her sari length so long that she just could not be stripped naked.

But this sinner Husain, by disrobing Draupadi has not only insulted this upright woman but has also mocked at the omnipotence of Lord Krishna. What sins Dushasana and Duryodhana could not commit, Hussein, in the name of art, has committed.

This is not the only sin committed by Husain… In his painting of Saraswati, he has depicted Mother Saraswati completely naked. Our eyes turn away with shame when we gaze at this painting of Hussein’s. The Goddess of Learning who is worshipped by Hindu and Muslim artists alike cannot ever be conceived of, let alone depicted, in this naked state. Only a man such as this, who nurtures a devil in his brain, can commit such a lowly act.

The former Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, has been depicted by Hussein as Goddess Durga. In that painting too, Durga was painted naked…

It is not even as if Maqbool Fida Husain is not aware that the mother is a figure deserving of respect. When he painted his own mother, Shireen, he had depicted her with deep respect. In this painting she sits in a demure position. Except her face, her entire body is clothed in a sari. Even her head is covered with the sari’s pallu (one end of the sari). She looks like the epitome of dignity.

When Husain depicts his own mother so gracefully and respectfully, why does he not have the same respect while depicting Durga and Saraswati whom hundreds of thousands of Hindus regard as their Mother? How should they be painted? Why does he not worship Mother Goddess Durga and Saraswati like he does his mother? Why don’t his eyes become the eyes of the devil when he is painting his own mother? Why is he, like the Pakistani and Bangladeshi fanatics and maniacs who destroy temples and deities, determined to reduce Gods and Goddesses to rubble?…

Recently, “stories” about Husain and Madhuri Dixit were published prominently in newspapers. Madhuri’s film Hum Aapke Hain Kaun was a hit worldwide. At this point Hussein declared that he would paint Madhuri. He wrote articles and poetry dedicated to her and declared, in the newspapers that he was “fida” (absolutely sold) on her.

He saw her film, Hum Aapke Hain Kaun fifty times. He said Madhuri was the epitome of Indian beauty. Among the paintings of Madhuri, there was one named, “The Rape of Europe” that depicted a saand (stud bull) named Maqbool raping Madhuri. In this painting again, Madhuri is depicted in the nude while a sex-crazed saand has shoved his head between her legs.

A person who has declared a woman the epitome of Indian beauty, whom he regards as the Mother Goddess, whom he strips naked in his painting, while he depicts himself as a saand raping her, is displaying the mind of a rapist. A sick man or a devil alone can conjure up such an image. No greater insult to love and beauty can be found anywhere in the world…”

(The next article published three days later, on October 9, 1996, in ‘Dopahar ka Saamna’ written by Sanjay Nirupam, its editor was entitled “Haraami Husain” (Bastard Husain). Excerpts:

“Let me begin by expressing sympathy towards Mumbai’s Muslims, who reacted sharply to the article written in our publication last Sunday on the betrayal and misdeeds of Hussein. The statement made there by our writer was posed as a hypothesis that readers must read as an example…

In a highlight that accompanied the article, we had raised a question whether the same Husain who had depicted our Goddesses with such dishonour and disrespect would have the courage to depict Mohammad the Prophet in the same fashion. This was a question to Husain. This was not a wish or desire of our writer! This is not even the culture of us Hindus. For us, the Gods, Goddesses and Great Men of all religions are worthy of respect.

In our minds, we have the same, if not more respect for Prophet Mohammad that we have for Lord Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesh. Hence those Muslims who were agitated by our writer’s question should please remove any doubts on our motives from their mind. But I would still like to ask a question to those Muslims. When a mere example regarding Prophet Mohammad can agitate their sentiments so greatly, how agitated should we get when see the naked paintings of our Goddesses?

The Muslims say, Husain is not our man. His good or bad deeds are not our responsibility. All right do not take the responsibility. But if you are true believers and followers of the Quran, then why did your blood not boil at Hussein’s bastardisation of art?

Islam claims to have respect for the Gods and Goddesses of all faiths. Then would it not have been in order that instead of Hindus first opposing Husain, his Muslim co-religionists had taken up cudgels against him?

This is not our expectation of the ordinary Muslim but of the Maulvi-Maulanas, who declare fatwas at a drop of a hat on minor and insignificant issues. Shahi Imam and countless Maulvis issue fatwas to garner votes. But when a Muslim called Husain insults the Goddesses of another faith, not a word of criticism?

This is wrong. At times like this, it is evident that even in the minds of the ordinary Muslim there is some devious intent. On the surface, of course, they say Husain is wrong. But it is possible that deep inside they find a gleeful satisfaction in observing the whole charade. Muslim society will have to declare its intent and remove our suspicion that they are enjoying a gleeful satisfaction. They will have to join Hindus in their relentless campaign against Husain.

They will have to tell spineless and worthless Hindus like V.P. Singh and Nani Palkhiwala that the definition of art and beauty is not limited to depicting divine figures naked. Or else the ordinary Hindu will get confirmed in his belief that what Hussein is doing, is the culture and tradition of Islam. Unfortunately, no other Muslim has ever done (within Islam and against the Prophet) what Husain has done (to Hindu Goddesses) and been left un-criticised by Muslims. One Salman Rushdie writes “Satanic Verses” and the world’s Muslims get angry.

Rushdie is not only excommunicated from Islam but there is public declaration of intent to murder him! But when Husain insults a Hindu Goddess not a single Muslim from Bhendi Bazaar gets angry. All of Muslim society will have to explain this silence.

Only yesterday, some of our associates had demonstrated their protest outside Husain’s house by performing a pooja of Goddess Saraswati. Even I had gone there. I was told that some women demonstrators had also come to protest against our protest. In the name of freedom of speech and expression, they were shouting slogans of protest against our protest, and in defence of Husain.

I would like to ask those women, how shameless can they get defending an artist with a sick mind like Husain who has depicted Goddess Saraswati naked? If Hussein had painted one of them naked, would they shout slogans in his support?

Even V.P. Singh declared that obscenity is not in the depiction of art but in the eyes of the beholder. Then why does he not move around naked? Why does he sport a spotless white kurta-pyjama in his countless jaunts between Delhi and Mumbai, Mumbai and Delhi? If he has any guts, let him roam Mumbai naked on his next visit. If he can, ask him to bring two-three naked women to accompany him and then let him tell those who see him thus that he does not make an obscene sight! And it is merely their gaze that makes the spectacle obscene.

Even Nani Palkhiwala has turned senile. He says the artist has full freedom of expression. I ask him: if Husain were, one day, to depict him mother, wife or daughter naked, would his blood boil or not?…

Let me remind all those persons who have descended to the streets in defence of Husain, of one thing: the fingers of the long-bearded traitor who has painted our Goddess Mother Saraswati, those fingers have also drawn his own mother, Shireen. We have published that painting. But the image of his mother is not naked.

Husain has painted his mother with her head covered demurely in a sari, the image of a woman accorded all proper respect. Why did Hussein not paint his mother naked? Is our much-revered Mother Goddess less worthy of his respect than his mother?

I ask the touts of Husain, who in the name of freedom of expression defend such calumny this question. If they do not have an answer let them go home and demand one from their mothers and sisters. If they praise Husain in front of their mothers and sisters they will be slapped by them…

The same Husain who after professing his love for Madhuri Dixit can paint a revolting picture… Husain is truly a sexually perverted artist. Whoever denies this is either foolish or mad or perverted himself. To defend Husain is to legitimise the crude and disrespectful in art. This will have to be understood by today’s artists.

Whatever Husain has done, he has wilfully done. He has to receive punishment for this, within the law or outside it. If he has so much faith in his art why did he run away to London? He is aware of his crime. He thinks that he will be able to return when the anger of Hindus has cooled down.

But Hindus, do not forget Husain’s crime! He has not to be forgiven at any cost. When he returns to Mumbai he must be taken to Hutatma Chowk and publicly flogged until he himself becomes a piece of modern art. The same fingers that painted our Mother naked will have to be cut off.

If Muslims are true followers of Islam, they must join their Hindu brethren in this Dharmayudh. There is also a word for the top echelons of the Mumbai police: if they genuinely want to sooth the simmering anger of Hindus, they must proceed to London and arrest and bring back Husain. Or else, these police officials will expose themselves as traitors. They must not forget that they are also Hindus.

Why did their blood not boil? And if it did why is there a delay in registering a case against Husain? We are not asking Husain? We are not asking that the police take action against Husain by violating the law. But while remaining within the law, surely the police could prevent Husain having a gay time in London.”

(This is archived from Communalism Combat, November 1996)