Mumbai: The Mumbai Fire Brigade (MFB) answers one call nearly every day regarding a building or its parts having crumbled, fire brigade data show.

There are now more than 14,000 buildings in Mumbai that are over 50 years old and which, due to age-related instability and lack of maintenance, are at risk of collapse. One such building collapsed on July 16, 2019, in Dongri, south Mumbai leaving 14 dead and nine injured, as we reported on July 16, 2019.

The number of such buildings is estimated from tax records–those dating prior to 1969 pay cess to the Maharashtra government for maintenance. Their number has fallen–as they have, literally (either in redevelopment, demolition or collapse)–from 19,642 in 1969 to 14,207 today.

Their rents being frozen under the Rent Control Act at decades-old rates, their owners are reluctant to spend on their upkeep, as The Print reported on July 17, 2019. Residents keep staying despite the risk, for the low rents and because, often, ‘transit’ accommodation (for those having to vacate dangerous buildings, provided by the municipal corporation concerned) is not available.

A 2018 disaster management plan of the Mumbai municipal corporation had flagged these buildings, then 16,104, for vulnerability to collapse.

“Apart from the legal hurdles, paucity of funds has slowed down the work of Mumbai Repairs Board considerably,” the document states. “House collapse is therefore a regular phenomenon and in the absence of adequate ‘transit’ accommodation and emergency shelters become a major requirement in the event of house collapse.”

City densely populated, poorly planned

Mumbai–the city and its suburban regions–home to more than 12 million people–is the second most densely populated city (31,700 people per square kilometre) in the world, after Dhaka (44,500), the World Economic Forum reported in 2017. A large section of this population lives in slums, more than 40% by some estimates.

Mumbai is prone to natural and man-made calamities such as floods; tree falls; structural collapses; landslides; fires in slums, buildings, high rises, industrial units and transport vehicles; and even terrorist attacks.

The city’s vertical growth in the form of highrises and skyscrapers to accommodate its growing population has happened with improper planning and inadequate safety measures, experts say. Old structures are already vulnerable, as we said.

“Mumbai is an old city which is into a rehabilitation phase where the rehab component plays an important role,” Prabhat Rahangdale, chief fire officer, Mumbai Fire Brigade and director Maharashtra Fire Services, told IndiaSpend.

Forty-five emergency calls every day

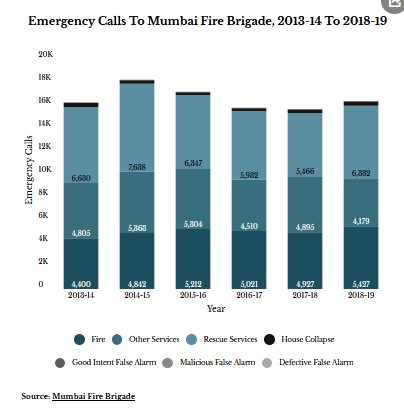

The Mumbai Fire Brigade received 99,393 emergency calls in the six years ending 2018-19, of which 1.8% (1,830) were for house collapse, official data show. This averages to more than 300 house collapse calls every year. These are mostly regarding collapses of minor walls, parts of buildings, parapets or extensions, wooden structures in old chawls and their extensions.

Rescue calls number the highest among emergency calls–38,345 or 39%, and include the rescue of birds, animals and humans. These are followed by fire calls (30% or 29,829) and those such as oil spillage or tree fall requiring other services (29,056 or 29%).

City’s old and new infrastructure vulnerable

As the data show, fire calls increased 10% over a year to 2018-19. On average, over the last six years, Mumbai’s fire brigade received nearly 5,000 fire calls every year. Short-circuit was the most common reason, fire officials told IndiaSpend.

The city has the “biggest number of high rises still, you can see the old buildings and old infrastructures. These old buildings have old-age wirings, most of the electrical panels are below the staircases,” Rahangdale said.

Too many of these buildings do not have proper evacuation plans. “Many people die due to smoke and less due to fire. So to prevent that you need to have a proper evacuation plan and ways,” said M V Deshmukh, director, government affairs, Fire Safe India Foundation and a former fire adviser to the government of Maharashtra. Many high rises in Mumbai have a single staircase whereas any building above 15 metre is required to have two. “People at large do not know and they have no choice,” he said, “When you and I go to buy a flat we start number one with the budget, number two with the basic amenities like parking, gym, swimming pool. But people don’t bother whether this building is safe.”

The numerous slums are “combustible in nature”, Rahangdale said, adding, “And to add to that the use of gas cylinders and the blast cause most of the injuries and deaths.”

Improper city planning

By allowing cities to grow vertically, we “exploit the available infrastructure beyond its capacity,” Deshmukh said. “This is not [just] a challenge for the fire service, it is a challenge from many other perspectives–like ambient air quality management, water management drainage, sewage management, traffic management.”

Mumbai is home to more than 130 skyscrapers. Some of these range from 100 metres (30-storeys) to above 250 metres (70 storeys), while the fire brigade’s ladders range from 25-90 m only–sufficient only to reach up to under 30 floors.

“If there is a 240-metre building or 300-metre building, in any part of the world there is no ladder which can reach up to that height,” Rahangdale said. “Internal systems like sprinklers, smoke detectors, pumps are an integral part of the building and has to be maintained properly.”

The Maharashtra Fire Prevention Act makes it the responsibility of the owner or occupier to provide fire prevention and life safety measures. The fire brigade’s inspection cells take “stringent action”, “but practically it is impossible to check each of the buildings,” he said.

“Safety is not a law. It is a culture,” Deshmukh said. The National Building Code lays down several provisions for building construction and for access roads to it; which is between 6 and 9 metres.

“If you are going to construct 100-150 metre tower with hardly any space around it, obviously you are blocking your own arteries with no bypass. If there is only one lane going to that building, then it is bad planning,” Deshmukh said.

Six metres is good enough to mobilise fire trucks and fire engines on a road, Deshmukh said. “But when I open the ladders or fire trucks arms, hydraulic jacks, it requires 7.5 to 9 metres space. Then I require the turning circle inside the building. If I enter from one side I have to move out from the other side,” he said, pointing out how tightly-packed buildings hinder rescue services.

The access road to the building that collapsed in Dongri proved a major hindrance to rescue operations by the fire brigade and the National Disaster Response Force. Dongri is situated in south Mumbai, which houses several old structures and buildings which are more than 100 years old, and is criss-crossed by hundreds of narrow streets.

“The building [which collapsed] is in a narrow lane which is 1.5 to 2 feet wide [less than a metre], because of which the NDRF vehicles carrying the rescue equipment could not reach the site,” S N Pradhan, director-general of the National Disaster Response Force said. The team had to march on foot carrying the equipment.

Traffic congestion

With 510 cars per kilometre, the most in the country, Mumbai reported the world’s worst traffic flow, as per a 2018 traffic index that assessed 403 cities in 56 countries.

To work around traffic delays, the fire brigade has set up 17 mini-fire stations across the city for a quick response.

“In one-and-a-half-year, we established more than 17 mini-fire stations. The fire engine goes very fast, it reaches to the incident and the backup is given by the main fire station… It is very successful,” Rahangdale said, adding that another 10-15 mini-fire stations will be set up in one and a half-year. “The control rooms and vehicles are now GPS-enabled, which helps to estimate the time required and the shortest route to reach the place of incident,” he said.

Illegal parking is another major hurdle, to prevent which the fire brigade is already working with the traffic department, Rahangdale said. The municipal corporation, in July 2019, increased the fine for illegal parking across the city, ranging from Rs 5,000 (for two-wheelers) to Rs 15,000 (for heavy vehicles); it can go up to Rs 23,250 for late payment.

(Mallapur is a senior analyst at IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend