Al Jazeera provides a graphic account of the Srebrenica genocide.

On July 11, 1995 at 16:15 General Ratko Mladic (now a convicted war criminal) entered Srebrenica with Serb forces, including paramilitary units from Serbia, claiming the town for Serbs. Strolling through the streets with the TV cameras rolling, Mladic announced that there will be “revenge against the Turks”.

Panicked residents in the enclave fled to the UN Dutch Battalion base only to find that the 400 lightly-armed peacekeepers were unable to defend them. Serb forces had inherited much larger resources of the former Yugoslav army, the fourth largest in the world at the time.

On that day, thousands of Bosniak men start to make their escape through the woods, forming a column and hiking some 100km in an attempt to reach free territory controlled by the Bosnian army.

The journey was known as the death march, as they were ambushed, shot at and attacked by Serb forces. Less than a quarter of them survived.

Over the course of six days, more than 8,000 Bosniaks were killed. Women and small children were deported.

In an attempt to conceal the killings, Serb forces transported the dead bodies with bulldozers and trucks and buried them in numerous locations, leaving the victims’ remains fragmented and crushed.

Human bones can be found as far as 20km apart, making it difficult for families to give their loved ones a proper burial.

What led to the massacre?

Genocide is not committed by a small group of individuals, rather a large number of people and the state all contribute to genocide.

The idea of a Greater Serbia (including the territories of Bosnia, Kosovo, Croatia, Montenegro and other neighboring countries) dates back to the 19th century, and was revived following the death of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980.

With the decline of the Communist bloc, Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic and Serbian nationalists saw a chance to mobilise the masses in support of establishing a homogenous Serbian state.

In Milosevic’s famous address to a crowd in Belgrade in 1989, he presented himself as the savior of Serbdom and Europe. It enforced the notion of “us [Serbs] vs them”.

Bosniaks were typically called Turks, Balije (a slur for a Bosnian Muslim) and branded as terrorists and Islamic “extremists”.

A plan to destroy Bosnia and “completely exterminate its Muslim people” was drawn up as early as the 1980s by the General Staff of the Yugoslav People’s Army, according to Vladimir Srebrov, a politician who cofounded the SDS party with convicted Bosnian Serb war criminal Radovan Karadzic.

One document, written by the army’s special services including experts in psychological warfare, stated that the most effective way to create terror and panic among the Bosniak population would be by raping women, minors, and even children.

How genocide was organized?

Organized from Belgrade, Serbia, weapons were distributed to the Serb population by the truckload throughout 1990 and 1991 in Bosnia, according to Al Jazeera.

“Weapons and military equipment were even flown in by military helicopters to Serbian military officers. It is said that by the end, almost no Serbian house was without an automatic gun,” according to a UN report from 1994.

“The pretext for the arms deliveries and the rearmament was that this was necessary for the defence against ‘the enemies of the people’ – the Muslim extremists.”

As Serb troops arrived in each town, they killed non-Serbs, often after torturing them. Bosniak properties were confiscated.

As many as 50,000 Bosniak and Croat women, girls and young children were raped in Bosnia from 1992- 1995.

In Prijedor, a city in western Bosnia, Bosniaks were forced to wear white armbands to be clearly identified and tie white flags to their doors.

Across the country 200,000 people were deported to concentration camps where they were tortured, starved and killed.

Others living under siege, such as in Sarajevo and Mostar, starved while being targeted by snipers and heavy shelling.

Srebrenica, which was known as the world’s biggest detention camp, was under siege for three years, before it fell to Bosnian Serb forces in July 1995.

Serb troops separated boys and men aged between 12 and 77 from the rest of the population and took them to fields, schools and warehouses to be executed.

International Court of Justice

The systematic murder of over 8,000 Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) in Srebrenica by Serb forces in July 1995 was ruled as an act of genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice.

Theodor Meron, the presiding judge at the ICTY, stated in 2004 that “by seeking to eliminate a part of the Bosnian Muslims, the Bosnian Serb forces committed a genocide.”

“They targeted for extinction of the 40,000 Bosnian Muslims living in Srebrenica, a group which was emblematic of Bosnian Muslims in general,” he said.

Serbian General Vladimir Lazarevic, Bosnian Croat Dario Kordic and Bosnian Serb Momcilo Krajisnik were convicted for “horrific crimes against humanity”, yet they were given a hero’s welcome upon release from prison with government officials in attendance, the report noted. Fourteen Serb war criminals were convicted of genocide and other crimes at the ICTY including former Military Commander Radislav Krstic, former President of Republika Srpska Radovan Karadzic, and Bosnian Serb Military Leader Ratko Mladic.

“All three, as senior officials and commanders, participated in ethnic cleansing and campaigns harming millions and devastating communities. The mentality that can regard those men as heroes is difficult to understand,” Meron wrote.

The systematic murder of over 8,000 Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) in Srebrenica by Serb forces in July 1995 was ruled as an act of genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice.Denial of facts established in the Tribunal’s judgments are widespread in the education system throughout former Yugoslavia, the report noted, where students are taught “widely different and irreconcilable versions of the recent past”.

International Court of Justice

Theodor Meron, the presiding judge at the ICTY, stated in 2004 that “by seeking to eliminate a part of the Bosnian Muslims, the Bosnian Serb forces committed a genocide.”

“They targeted for extinction of the 40,000 Bosnian Muslims living in Srebrenica, a group which was emblematic of Bosnian Muslims in general,” he said.

Serbian General Vladimir Lazarevic, Bosnian Croat Dario Kordic and Bosnian Serb Momcilo Krajisnik were convicted for “horrific crimes against humanity”, yet they were given a hero’s welcome upon release from prison with government officials in attendance, the report noted. Fourteen Serb war criminals were convicted of genocide and other crimes at the ICTY including former Military Commander Radislav Krstic, former President of Republika Srpska Radovan Karadzic, and Bosnian Serb Military Leader Ratko Mladic.

“All three, as senior officials and commanders, participated in ethnic cleansing and campaigns harming millions and devastating communities. The mentality that can regard those men as heroes is difficult to understand,” Meron wrote.

Canadians launch petition to ban Srebrenica genocide denial

Denial of facts established in the Tribunal’s judgments are widespread in the education system throughout former Yugoslavia, the report noted, where students are taught “widely different and irreconcilable versions of the recent past”.

An online petition has been launched in Canada by the Institute for Research of Genocide (IRGC), requesting the Canadian government to enact a law making Srebrenica genocide denial a punishable offence.

If the petition is adopted, Canada would join nine other countries in Europe including Switzerland, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia and Macedonia in prohibiting genocide denial.

Canada has already adopted two resolutions recognizing the Srebrenica genocide, launched by the IRGC.

However, its Director Emir Ramic noted that the process of adopting the first resolution took five years as the Conservative Party – under the influence of the Serbian and Russian lobby – had rejected the resolution.

He told Al Jazeera that the threats intensified as discourse changed from denial to glorification and triumphalism.Ramic’s work with the institute has made him a target of death threats and verbal abuse for years by genocide deniers.

However, he says it has made him all the more determined to make sure a law is enacted banning the denial of Srebrenica genocide. If adopted, Canada would make a major contribution in the fight against genocide denial worldwide, Ramic told Al Jazeera.

“Denying the genocide in Srebrenica is very dangerous. We need to learn from history, recognise [what happened in Srebrenica] and call it by its real name,” he said.

“The aggression and genocide in Bosnia have shown that … there aren’t adequate mechanisms in place to protect freedom and human rights.””Human rights are under attack worldwide,” Ramic added. “Bosniaks, as the only people in Europe who survived aggression and genocide [since the Holocaust], are exposed to unacceptable discrimination not just in the motherland, but in the Diaspora as well.”

“We’ve seen this with Holocaust denial, we’ve seen this with denial for Rwanda and of course with Srebrenica,” said Parliamentarian Brian Masse on the necessity of a law.

“It’s very hurtful for the victims and families of the survivors to continue to wrestle with something based on facts, so the initiative will help in preventing denial and create awareness that we will never forget.”

On April 24, 2015, the House of Commons passed a motion to include the Srebrenica genocide, and Srebrenica Remembrance Day as part of “Genocide Remembrance, Condemnation and Awareness Month” every April. Earlier on October 19, 2010, the House of Commons passed a motion to recognize July 11 annually as Srebrenica Remembrance Day in Canada.

Abdus Sattar Ghazali is the Chief Editor of the Journal of America (www.journalofamerica.net) email: asghazali2011 (@) gamil.com

Courtesy: Counter Current

Gumla, Latehar, Koderma (Jharkhand): Mohamed Shalik knew his attackers. Imamul Haq did too. As did Majlum Ansari.

Saira Bibi and her daughter at the family’s house in Nawada village of Jharkhand’s Latehar district. Manowar Ansari is seen in the background. When Manowar reached the spot where cow vigilantes had attacked and killed his brother and Bibi’s husband Majlum, he was shocked to see that the two men leading the mob were his brother’s acquaintances.

Each of these three victims of mob lynching in Jharkhand, India’s second deadliest state for hate crimes, knew the members of the mob that attacked them. Shalik and Ansari were lynched, Haq sustained severe injuries that left him bedridden for six months.

During its investigation of seven crimes motivated by religious hatred across six districts of Jharkhand, FactChecker found that in at least four cases, the mob included friends and acquaintances of the victims. Religious hatred has spurred people to violence against schoolmates, childhood buddies and colleagues, forgetting old ties that lie severed ever since.

This is the last in a series of five stories from Jharkhand, which has reported 14 hate crimes and nine deaths since 2009–the second-deadliest state after Uttar Pradesh (23 dead)–all reported after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the general and state elections in 2014, according to our Hate Crime Watch database. Reporting for this series coincided with the recent national elections, in which the BJP won 11 of 14 parliamentary seats in Jharkhand.

Traveling across 3,000 km in 13 days, FactChecker visited sites where hate crimes had taken place, met victims’ families, the accused, local residents and police officials. The aim was to investigate the cases, find out what has happened since and document the long-term impacts of hate crime on the lives of people and communities.

In most cases, hate crimes had been provoked by hatred powerful enough to consume community and neighbourhood relationships. The hatred they inflamed seemed to have caused lasting damage to social relations.

Childhood friends, now strangers

Imamul Haq, 24, grew up in Kolgarma, a predominantly Hindu village in Koderma district of northern Jharkhand. He was never conscious of his identity as a Muslim, he told FactChecker on a scorching April day.

In school, his closest friends had all been Hindu boys from the village. “So, I would never be at home, except for my meals. After school, we would spend the day together, playing, goofing around. We would even do our homework together,” Haq said.

As a teenager, Haq was roped in by Hindu villagers to take part in the festivities around the popular Hindu festival of Ram Navami–a spring Hindu festival that celebrates the birthday of Lord Rama of Hindu mythology. He soon went on to become the village’s go-to actor for Ram Navami plays. “Sometimes, when I would be busy and not able to make it to the festivities, my friends would be so upset, they would not talk to me for days,” he said.

All that changed in 2017, ironically, on Ram Navami, which fell on April 4 that year.

A dispute between Hindu and Muslim villagers over the inauguration of a mosque, built on a contested piece of land, caused such tension that Haq did not participate in Ram Navami celebrations that year.

In the evening, Haq was offering his namaaz at the newly-inaugurated mosque when a mob of more than 200 people attacked. “They kept saying Jai Shri Ram [Hail, Lord Ram] and Quran padhna band karo [Stop reading the Quran], even as they assaulted me with sticks, rods and swords,” Haq said.

By the time Haq’s mother rushed in to save him, both his knees had been battered, leaving him bedridden for six months and unable to resume his lucrative job as a driver in Saudi Arabia. “The legs hurt so much even now that it is impossible for me to do any work involving my feet,” he said.

Imamul Haq, 24, outside the disputed mosque in Kolgarma village in Jharkhand’s Koderma district that was attacked by a 200-strong mob from a Ram Navami procession in April 2017. Haq and a few others who were praying inside the mosque were assaulted with sticks, rods and swords. Haq’s Hindu friends have since cut off all ties with him. To Haq, their silence makes them complicit with his assaulters.

Since then, his Hindu friends have cut off all ties with him, he said. “When I met them on the streets and called out to them, they didn’t even turn back. They would look away and walk on. These were people I spent my childhood with,” said Haq, in his measured, soft-spoken manner. “I tried my best to reach out. But the Hindu community imposed a social boycott on us–any Hindu found talking to us would have to pay a penalty.”

To him, his Hindu friends’ silence makes them complicit with his assaulters, he added.

Old ties forgotten

On March 18, 2016, 28-year-old Manowar Ansari got a call from family friend Nizamuddin that his cattle-trader brother Majlum, 32, had been attacked by a mob in Jhabar village in Latehar district. In the 15 minutes it took him to reach Jhabar, Manowar had feared many possibilities. But nothing, he said, had prepared him for what was happening: a mob had surrounded his brother and his fellow cattle-trader, 13-year-old Intiyazul Khan, and were assaulting them. The assault continued for some time before the mob dragged the two, still alive, to a large tree a few metres away.

Then, Manowar said, the mob hanged his brother and Khan. The two tried to free themselves. “So, people started pulling my brother’s legs from the ground to ensure he died,” Manowar said.

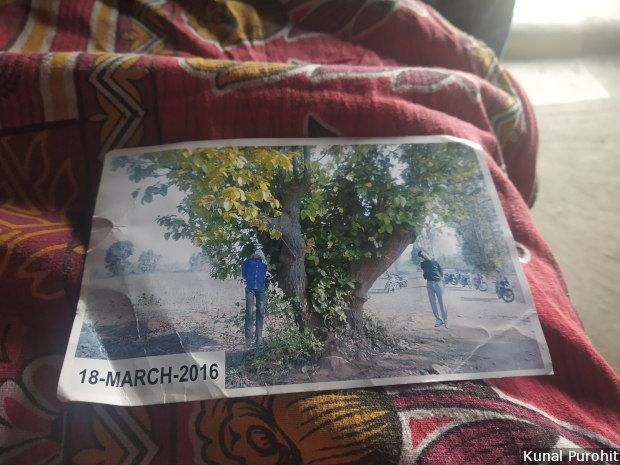

Families of both victims have retained, carefully, this image showing the bodies of 32-year-old Majlum Ansari and 13-year-old Intiyazul Khan, hanged from a tree. Cow vigilantes, led by men who were Ansari’s acquaintances, had assaulted these two cattle-traders in Latehar district of Jharkhand when they were taking oxen to a cattle fair, before hanging them alive.

In that small crowd was a familiar face–Bunty Sahu, later named the main accused in the case.

“Sahu knew us very well. He knew my brother so well. In fact, when my brother was making a new house, he had bought cement and other construction materials from Sahu’s shop,” said Mohamed Afzal Ansari, 46, Manowar and Majlum’s older brother.

The Ansari family later learnt that it was Sahu who had first apprehended the two cattle-traders and called up Arun Sahu, the other main accused in the case.

Arun, too, was a familiar face. Some months before the incident, Arun had threatened Majlum and asked him to stop trading in cows. “So, Majlum told him he didn’t deal in cows anyway. He only dealt in oxen, used for agricultural purposes. Majlum asked Arun if he should stop doing that, too,” Afzal said.

Arun “allowed” Majlum to continue, the family said.

Yet, Arun went on to lead the attack. “He was from the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh]. He was said to be close to top BJP leaders here,” Afzal said of Arun.

That their brother’s killers were people so familiar with him and his work is a fact that still hurts Majlum’s family. So does the location of the assault–Jhabar village.

“Jhabar was a village my brother Majlum had visited tens of times. In fact, he had sold and bought countless cattle from the Hindu families there. Would they have allowed him to trade if he was selling the cattle for meat?” said Afzal.

Community ties severed

For families of hate crimes victims, the silence of friends, neighbours and other villagers becomes a sign of complicity.

“If you let such a crime happen in front of you, it means you’ve tacitly supported it,” said MD Minhaj, a 52-year-old shopkeeper and businessman of Gumla town, after his daily visit to the cemetery where his son, Mohamed Shalik is buried.

Shalik, 20, was lynched by Hindu villagers of Soso, a village 5 km from Gumla town, on April 5 in 2017. The villagers claimed Shalik was harassing a girl from the locality; Shalik’s family as well as the girl’s insisted the two were friends.

According to the first information report (FIR) filed with the police, Shalik was tied to an electric pole just off the Lohardaga road and lynched, with rods and sticks.

When Minhaj reached, Shalik was “adhmara” (half-dead)–slipping in and out of consciousness, his limbs seemed broken, his intestines were hurting. “He said two-three things constantly–he kept asking for water and kept repeating that his stomach was hurting, there was a leher [wave of pain] inside.”

Shalik died in the Gumla Sadar hospital 20 minutes later. But before that, gasping for breath, he managed to tell Minhaj the names of some of the people who had assaulted him. “All the six people he named were those who knew Shalik very well. They were his friends and acquaintances, some even went to school together with him,” Minhaj said. “They took the lead in lynching him. The other villagers joined in, because he was a Muslim.”

The house where Mohamed Shalik was found lying half-dead, the night he was lynched after being tied to a pole, in Soso village near Jharkhand’s Gumla town. Shalik had many Hindu friends from this area, and his school was nearby. His father M D Minhaj later found out that some of Shalik’s acquaintances and old friends had taken part in the lynching.

Six of the main accused were familiar to Minhaj, too. “All of them used to come here, meet me, come to the shops as well. All of them were locals so we knew them very well,” he said, asking his older son to bring out Shalik’s photo. “For two years, I haven’t seen his photo. I can’t bear to look at it.”

Minhaj said he did not know why his son was attacked. But, he links his son’s killing with other hate crimes in the country. “There were two major themes in the air then–love jihad and gau-raksha. This must have egged the mob on,” Minhaj said, pointing to a news clip in a local Hindi newspaper, which reported that Shalik had tried to marry and abduct the girl, painting it as a case of ‘love jihad’, a phrase often used by the Hindu right-wing to describe a relationship between a Hindu woman and a Muslim man.

Minhaj continues to attend to both Hindu and Muslim customers at his shops in the heart of Gumla town’s commercial areas. It is difficult, he said, but he is determined to ensure nothing changes between the two communities after his son’s killing.

“After news of my son’s killing reached the Muslim neighbourhoods in Gumla, many were angry and suggested that we take revenge by attacking Hindu shops. But, I dismissed all such thoughts. I told them this was not acceptable,” Minhaj said, adding, “The Hindu community stood behind me. In fact, I received greater sympathy from them than the Muslim community.”

This concludes our five-part series. You can read the first story here, the second here, the third here and the fourth here.

(Purohit is an independent journalist and an alumnus of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. He writes on development, gender, right-wing politics and the intersections between them.)

Courtesy: factchecker.in

Diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2008, former consultant Raj Iyer, 69, has seen his once-itinerant life shrink to his bedroom in eastern Bengaluru, where he lives amidst his life-support equipment, including a 24-hour oxygen supply.

His itinerant, fulfilling life changed 11 years ago when he repeatedly felt short of breath and was eventually diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which had debilitated his lungs and his ability to breathe.

Smoking 60 cigarettes a day for 40 years was probably the immediate cause, although worsening air pollution may have played a role. “I knew my symptoms were of a respiratory disease but I didn’t know it was COPD,” said Iyer. “I certainly didn’t know how bad it gets or that it is incurable.”

Today, Iyer is 69, and his once expansive life has shrunk to a room in his house in Bengaluru’s eastern Pai Layout, where he lives with his primary caregivers, his 34-year-old son and 27-year-old daughter-in-law, whose lives, as we explain later, are circumscribed by his illness.

“When I first got married (in 2012), his COPD was not as bad, and he didn’t need continuous oxygen support,” said Antara Karthikeyan, Iyer’s daughter-in-law and a kindergarten teacher.

As the COPD progressed, Iyer needed oxygen support, multiple hospitalisations because of breathlessness caused by high levels of carbon dioxide–which is toxic to the body and accumulates when COPD affects ability of the lungs to expel carbon dioxide–and fell frequently due to his weakening bones.

Iyer’s room is taken over by the paraphernalia of his life-support system. A “BiPAP machine”, which is a respirator that steadies his breathing. A portable oxygen concentrator to take along while travelling. A larger oxygen concentrator, a machine that scrubs nitrogen from the air and give him a stream of pure oxygen through a 7-m-long plastic tube that allows him to move around the house. And to keep the life-giving gas flowing even when the electricity cuts out in India’s IT capital, notorious for its shaky power grid, the oxygen concentrator is connected to an inverter.

If Iyer’s professional and personal life followed India’s physical and economic transformation, so did the trajectory of the little-known, ill-managed disease that ravages his body–and is killing more Indians than ever before in a country with growing air pollution, more smoking among young people and an ageing, vulnerable population.

An incurable and progressive disease, COPD moved up from eighth spot to second on the list of leading ways to die in India, over 26 years to 2016 (the year for which the latest data are available). COPD claimed more victims than either road accidents or suicides in 2016. It claimed more lives than diabetes, malaria, tuberculosis and breast cancer combined in 2016. It only trails heart disease in the number of Indians it kills.

COPD is responsible for nearly a million deaths every year, as IndiaSpend reported in March 2019, in the first part of this series. The second part explained the contribution of traditional stoves burning coal, wood and cow-dung to COPD in India. In this, the third part, we bring you the story of a nation’s toxic air, a dangerous habit and a man being slowly claimed by a disease killing more Indians than ever before.

The fourth part will explain how India is unprepared for its COPD crisis.

Air pollution, smoking and ageing

Tobacco smoking is the primary cause of COPD worldwide, and it is responsible for a fourth of all cases in India. But air pollution–including ambient and household pollution due to biomass burning–is the primary cause of COPD in India and is responsible for more than half (53%) of all cases.

The ambient particulate pollution in India rose 12.5% over 27 years to 2017, from 80 μg/m3 (microgram per cubic metre) in 1990 to 90 μg/m3 in 2017, whereas China reduced its ambient particulate pollution from 58 μg/m3 to 53 μg/m3 over the same period.

These are “population weighted annual means” measuring fine particles, either dust or smoke, that penetrate the innermost recesses of the lungs. Averaged across the country, these data give weight to areas in proportion to their population, so that greater weight is given to areas where more people live. But these averages mask local concentrations of toxic air that may be many times more than the average.

In addition, more than 266 million Indians use tobacco, according to a 2018 World Health Organisation factsheet, and while the most common way to die of tobacco is from cardiovascular disease (48%), the next is chronic respiratory disease (23%), which includes COPD.

Although the proportion of any smoking among men aged 15 to 69 in India fell 27% over 12 years to 2010, cigarette smoking rose two fold in that age group and four fold in the 15-29 age group, according to a 2016 paper in BMJ Global Health, a journal.

“Despite modest decreases in smoking prevalence, the absolute numbers of male smokers aged 15-69 years has increased substantially over the last 15 years,” said the paper. Iyer started smoking when he was 17 and did not quit until a year before he was diagnosed with COPD.

A compounding factor in COPD’s rise in India is its ageing population, since there is growing evidence that susceptibility rises with age.

Over 21 years to 2011, the number of Indians above the age of 60 rose 93% from 53.7 million to 103.8 million. The decadal growth in elderly population between 2001 and 2011 was 35.5%, compared to 17.7% growth in the general population.

As the country ages and air pollution rises, COPD is likely to be increasingly common in India, experts told IndiaSpend.

India now accounts for a third (32%) of all disability adjusted life years (DALYs)–an indicator of overall disease burden–for COPD worldwide. Over 26 years to 2016, there was a 54% rise in the share of COPD in India’s total disease burden, as COPD moved up from being the eighth-leading cause of death to the second, according to the 2017 India: Health of the Nation’s States report by the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), a think tank, and the Indian Council for Medical Research, a government-run network of research laboratories.

Within this rise of COPD, there are medical nuances that explain why the disease is poorly understood, even by doctors, and poorly managed, claiming more Indian lives than it should.

Why so many Indians die of COPD

When Iyer felt the first shortness of breath, constant cough and tiredness in 2006, he went to a cardiologist who suspected it to be respiratory and cardiac related. The doctor prescribed medicines for both and despite symptoms getting worse, Iyer continued to work and travel.

Two years later, when he was alone, Iyer’s blood sugar levels dropped and he asked his driver to take him to a hospital. There, a number of tests later, his condition was correctly diagnosed as COPD.

It should not have taken two years for a diagnosis because Iyer has been a smoker since he was 17 and smoked, as we said, up to 60 cigarettes a day for 40 years.

As in Iyer’s case, a classic COPD symptom is shortness of breath, although other symptoms can include fatigue, cough and tightness of the chest. Patients feel short of breath because the tubes carrying oxygen to air sacs in the lungs are inflamed–chronic bronchitis–or because smoke damages these sacs, which is emphysema.

Either way, the lungs do not expel carbon dioxide or absorb oxygen as they should, even as airways are inflamed, making breathing difficult. This is especially difficult for older patients.

“At the age of 25, our lungs are at their optimum efficiency [taking in] around four to six litres [of air with every breath]; from then on, it gradually declines about 25-30 ml per year,” said H B Chandrashekar, director of the Jain Institute of Pulmonology and Sleep Medicine at the Bhagwan Mahaveer Jain Hospital, Bengaluru. “For smokers, this is two or three times faster, so about 80-90 ml decline each year,” said H B Chandrashekar.

So, by the time a smoker reaches the age of 45, the lung capacity is equivalent to a 75-year old’s, he said. Iyer, as we said, was 58 when diagnosed.

All his adult life, Iyer’s mother and friends told him to quit smoking. In 2007, he finally did. A year later, he was diagnosed with COPD. By then, he was in the second stage of the disease, meaning his COPD was moderate with symptoms worsening on exertion.

COPD patients say they are perfectly normal before but the fact is that lung function has been on decline that hey noticed because of aging, said Rajani Bhat, consultant physician, pulmonologist and critical-care-medicine specialist, who treated Iyer for eight years.

“Usually patients come to COPD as an exacerbation of a bad lung infection,” said Rajani Bhat, consultant physician, pulmonologist and critical-care-medicine specialist, who treated Iyer for eight years. “They say that they were perfectly normal before, but the fact is that their lung function has been on a decline for sometime, but they felt it only later because of aging.”

If caught early, ideally in full body health checks that include lung-function tests, COPD can be treated and managed through inhalers, usually bronchodilators, that open airways and make breathing easier, even though there is no direct cure.

There are several reasons why COPD is not diagnosed early by most Indian doctors:

“In our own study, we found that 25% of patients admitted with myocardial infarction [heart attack] had an underlying lung disease which was not known,” said B V Murali Mohan, Consultant, Pulmonology and Internal Medicine, at Narayana Health, Bengaluru.

Unlike heightened general awareness of India’s number one killer–cardiovascular disease–COPD is seldom written about in the popular media.

“It (COPD) is not considered of reader or viewer interest,” said Srinath Reddy, PHFI president. Coupled with poor diagnosis in primary care, confusion with other respiratory diseases and “low self referrals” by patients, COPD is an ill-understood disease, said Reddy.

Living with COPD

Iyer has watched COPD gradually take over his life.

From stage two in 2008, the disease within him has progressed to stage four, which means it is now in very severe stage where hospitalisations are frequent and lung function is limited.

Over the last four years, he has been hospitalised 10 times, mostly with a lung infection or low oxygen saturation in the blood.

In 2019, Iyer has only been hospitalised in January.

“They say if you have not been hospitalised for more than six months, you are doing well,” said Iyer. He has become adept at managing his disease at home, adjusting his BiPAP machine, running his nebuliser, which deliver medication to open his airway in a fine mist, and has avoided going to the hospital.

“Most patients, especially women, do not want to burden their children and family (and) hence wait till it is too late to see a doctor,” said Bhat, Iyer’s doctor. This is being penny wise, pound foolish, she said, since regular follow-ups ensure patients do not need to be hospitalised frequently.

Since most COPD cases in India are detected late and in stage 2 and beyond, they need frequent hospitalisation, especially in winter.

Iyer spends between Rs 10,000-15,000 every month on managing COPD, but each hospitalisation that usually lasts a week can cost between Rs 60,000-100,000.

Apart from the medical paraphernalia that keeps him alive, opposite his bed is a blackboard, on which daughter-in-law Antara Karthikeyan has written a list of medicines he needs to take every day and in case of an emergency.

Raj Iyer’s COPD was first thought to be a cardio-respiratory problem. By the time he was diagnosed with COPD, two years later–a year after he quit smoking–the disease was in its second stage, at which point there were moderate symptoms that worsened on exertion.

Given his research background–he has a master of philosophy degree in social anthropology–Iyer has studied the disease’s mechanism extensively and answered questions on treatment and medicines with ease.

“To treat COPD, doctors prescribed steroids, which in-turn bring on diabetes and osteoporosis,” said Iyer. “Because COPD makes you breathless, you are less active, which further weakens bones and muscles.”

Inhalers do not cause these side-effects; only the oral steroids, said Bhat, his doctor. “Iyer has to take oral steroids for his exacerbations and he has had to take them over a long period of time” she added. “However he wouldn’t be alive, if not for those medications.”

Yet, COPD detected early can be managed, and patients can hope for better quality of life.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

An intervention that works as effectively, if not better, than medication for COPD is pulmonary rehabilitation, which includes a 12-week programme of exercises for chronic lung patients under medical supervision, nutritional counselling and breathing techniques.

Exercise improves a patient’s breathing capacity by working muscles that become deconditioned due to disuse; it “empowers” patients and gives them confidence, so they can be independent, explained pulmonologist H B Chandrashekar of Bhagwan Mahaveer Jain Hospital who set up Bengaluru’s first, and one of India’s earliest, pulmonary rehabilitation centres in 2012 in the hospital.

“Exercise reduces chance of exacerbation, hospitalisation, improves symptoms and even may reduce mortality,” says pulmonologist H B Chandrashekar of Bhagwan Mahaveer Jain Hospital, Bengaluru. He set up the city’s first, and one of India’s earliest, pulmonary rehabilitation centres in 2012.

“Exercise reduces chance of exacerbation, hospitalisation, improves symptoms and even may reduce mortality,” said Chadrashekar. Most patients are reluctant to go into rehab, as they consider it unnecessary, and most hospitals do not have such a centre, since it does not bring in as much revenue as hospital beds do, he said.

Living in Bengaluru possibly took a greater toll on Iyer’s health. Pulmonologists explained how Bengaluru’s unique weather and geographical conditions make its residents especially prone to respiratory illness.

While air pollution is not as high as in New Delhi or in other northern cities–15 of which rank among 20 of the world’s most-polluted cities–Bengaluru’s altitude of 3,020 ft or 920 m above sea level and equable climate ensure pollutants do not rise, as they would in warmer weather, but stay close to the ground.

“The treeline in the city, with trees on both sides of the road, are the city’s lungs [but] also trap the pollutants close to the breathing zone,” said Bhat. The city’s high pollen concentration makes residents prone to allergies, asthma and COPD.

When Iyer was first recommended pulmonary rehabilitation in 2008, he didn’t take it seriously. In 2015 when his condition worsened, he went to Mahaveer Jain Hospital and accepted the rehabilitation.

He went to the hospital in a wheelchair with oxygen support; slowly he weaned himself off the wheelchair and constant oxygen support. In 2015, he felt better and was physically capable of doing more.

Iyer pointed out that insurance companies do not cover pulmonary rehabilitation. “They are willing to cover COPD and pay tonnes and tonnes of money, if you claim insurance,” he said. “But (they) will not pay for rehab that will prevent hospitalisation and save them money.”

The rehab costs Rs 1,000 a week, during which there are three one-hour sessions. Iyer paid for and continued rehab sessions for a year and was strong enough to achieve important milestones: his son’s wedding, buying property and travelling.

However, after a series of falls and injuries, he was not able to continue rehab after 2017. As his conditioned worsened, a greater burden is apparent on his family.

How families cope with COPD

COPD has altered the way Iyer’s family lives.

His son and daughter-in-law cannot, for instance, travel out of the city at the same time.

Daughter-in-law Antara Karthikeyan was once a retail manager with long working hours, but she was constantly worried about Iyer home alone.

“My number one concern was, what if he trips and falls,” said Antara Karthikeyan. “He cannot get up on his own. How will he call us?”

Her decision to become a kindergarten teacher, so she could return home by afternoon, was a personal choice, she said. She and her husband have hired help to look after their four-year-old daughter, Tanya, and be available in case Iyer needs assistance while Antara Karthikeyan is at work.

COPD does not affect only the lungs but causes wider systemic damage because of inflammation. The disease has brought gastritis, diabetes, oedema, sleep disturbance, anxiety and depression to Iyer, who uses music, reading books, watching documentaries and meditation as a way of making peace with his body’s slow degeneration.

This is the third of a four-part series. You can read the first part here and the second part here.

Reporting for this article was supported by the REACH Lilly Media Fellowship Programme on Non Communicable Diseases.

This story was first published here on Healthcheck.

(Yadavar is a special correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend

CUK had invited applications for 69 teaching positions through an advertisement issued on 14 June 2019. Among them 15 posts were for professors, 29 for associate professors and 25 for assistant professors in the departments of humanities, science, commerce, education, law, social sciences and languages.

In the original advertisement, among the 44 posts of professors and associate professors, none were reserved for the OBCs while among the 25 posts of assistant professors, five were set aside for them. Three posts of professors were reserved for SCs and one for STs. Of the 29 posts of associate professors, five were reserved for SCs and three for STs.

Except for OBCs, positions were assigned for all other categories, including Economically Weaker Sections (EWS).

Following protests, the university administration issued an amended advertisement on 5 July 2019, reserving three (of the 15) posts of professors and seven (of 29) posts of associate professors for the OBCs.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum

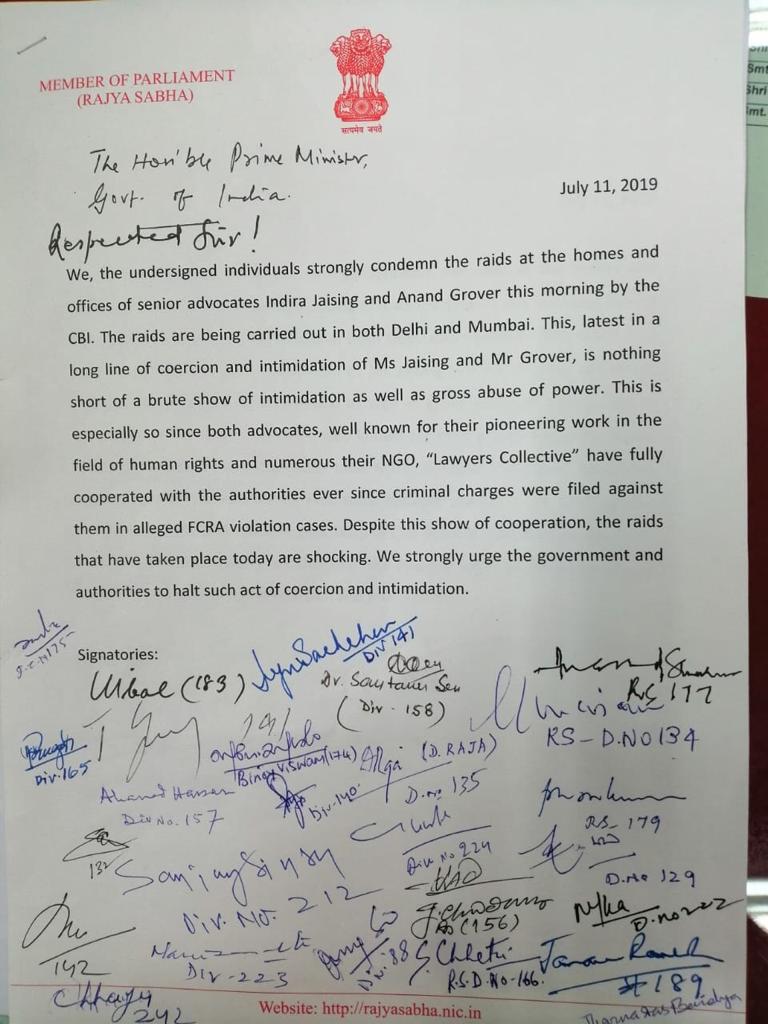

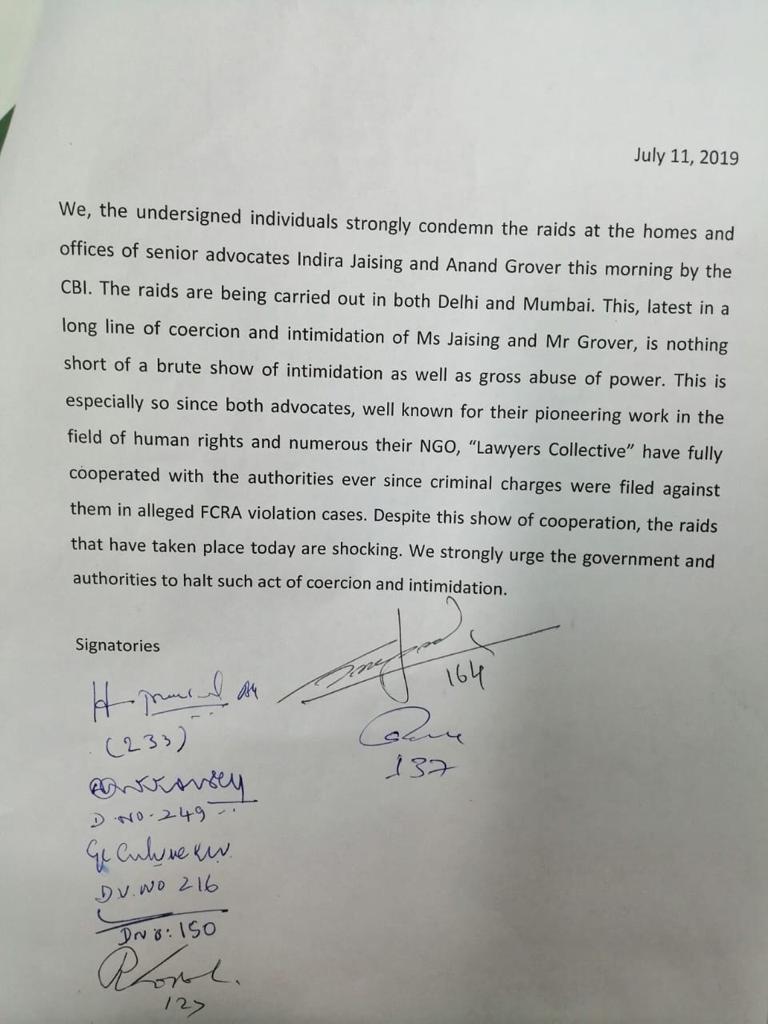

In this episode of Aaj Ki Baat, Urmilesh talks about raids on house and offices of Indira Jaising and Anand Grover.

Courtesy: News Click

Bengaluru, Mumbai & Kolkata: There was no–and never has been–electricity in the thatched-roof home that Rukhsana (name changed) shares with her parents. A small light flickered in the dark at the end of a row of paddy fields at the 16-year-old’s home in Basanti town in South 24 Parganas, West Bengal’s largest district and one of the “source districts for human and child trafficking” in India.

Rukhsana was sexually attacked thrice in four days by a man who had coaxed her into eloping. Yet, she is relatively lucky because she managed to escape, unlike thousands of girls abducted and forced into a life of sexual slavery, for whom there is no way back.

Rukhsana thought she was in love with the man she had met outside school. “During my conversations with him, he told me that he loved me and that his mother had passed away,” Rukhsana told IndiaSpend. It was only later, after she had escaped and found support from anti-trafficking counselors, that she realised that this man was probably a trafficker. She had not known of the concept before.

Like Rukhsana, thousands of girls in West Bengal are lured or forced into trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation (CSE).

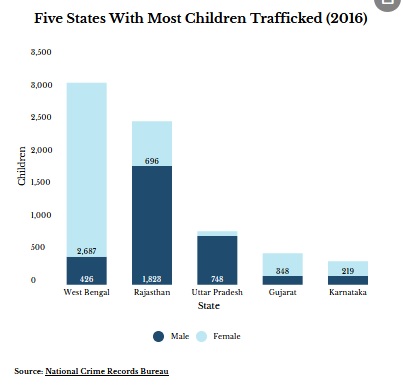

In 2016, the year for which the latest data are available, West Bengal reported the most children trafficked–3,113 or 34% of all–according to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. Of these, 86% or 2,687, were girls.

The state also reports more human trafficking than any other in India: the highest number of persons trafficked (4,164 or 28%), the most cases reported (3,579 or 44%) and the highest crime rate (3.81 human trafficking cases reported per 100,000 population).

“Trafficking for CSE was reported to happen in the context of girls eloping with boyfriends who then sold them into trafficking, or girls falling prey to fake marriage proposals and fake job offers,” according to a 2018 report from World Vision India, a charity.

Other reasons that led to trafficking were poverty–parents had no choice but to accept disguised job offers for their daughters–and kidnapping, the report titled Combat Child Trafficking For Sexual Exploitation In West Bengal said.

‘I ran away… as he went to buy a ticket’

In August 2018, Rukhsana travelled with the man in a “night coach”–that is, a sleeper bus. “Initially, he was well-behaved, but after the incident, I felt that he was bad,” she said.

“He laughed when I asked him to take me back home,” she said. “Although I thought of running away and coming back home, I never got a chance initially because he was always around.”

Eventually, she got suspicious when she heard him speak in Hindi, a language she does not understand, and say “Delhi”.

“I ran away when he made me wait as he went to buy a ticket, which I think was to Delhi,” said Rukhsana.

After travelling four-to-five hours by train, from a station whose name she does not remember, Rukhsana reached Sealdah station, about 70 km from Basanti. She had the Rs 100 she had taken when she had left home; she used it to get back home.

Although she is scared that the trafficker may come back, Rukhsana is among the few who were able to return home. He has not been traced yet.

“I will tell other girls not to go ahead if they see strangers trying to befriend them,” Rukhsana said.

Low awareness

About 59% adolescents did not know of any way to protect themselves from trafficking, and 72% did not know about services that could help them, the World Vision India study found.

It examined issues related to child trafficking for CSE in three districts of West Bengal–Kolkata, Darjeeling and 24 South Parganas. West Bengal is a focus area as three of the state’s districts–North 24 Parganas, South 24 Parganas and Murshidabad–lie along the porous international border with Bangladesh and are prone to trafficking. The state also shares borders with Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand, Sikkim and Assam, along with Nepal and Bhutan, making trafficking easy.

The study surveyed 136 women trafficked for CSE in the destination areas, 885 adolescents (aged 12-17 years) in the source areas, and 1,180 caregivers–people who spent the most time looking after the children, such as the biological mother, aunt, grandmother or father.

In addition, qualitative studies were conducted which included 12 focus group discussions with 211 participants, 13 key informant interviews–with police personnel, NGO workers and government officers involved in anti-child trafficking work–and 10 in-depth interviews with women in CSE. The surveys and interviews were conducted in February 2018.

As many as 52% caregivers and 45% adolescents in the source areas said they were aware of trafficking, while 14% of caregivers said they knew of trafficking incidents in their area in the preceding 12 months.

In the destination areas, 26% women in CSE who were surveyed said they had started as minors; 44% between 18 and 25 years, and 29% at 25 years and above. The median age for first sexual experience was 15 years; 43% of women said it was forced. Nearly half the women in CSE had encountered sexual violence prior to getting into it, the report said.

Anti-trafficking units resource-starved

Anti-human trafficking units are currently under-resourced and need more funding, said Michelle Mendonca, a Mumbai-based advocate.

Mendonca has been handling child- and sex-trafficking cases for 14 years now, and has trained judges and prosecutors on these issues.

“The police lack resources to conduct an in-depth investigation if the child is trafficked from a different state,” Mendonca said, adding that the police need to be held accountable once they are trained in dealing with cases of trafficking. They also need more resources.

Citizens can help by volunteering to be witnesses on sex trafficking rescues, and then providing evidence in court, said Mendonca.

Poverty and desperation lead people to unsafe migration, making them vulnerable to trafficking.

“But another important factor which enables trafficking is the culture of impunity,” said Mendonca. “The same recruiter can repeatedly traffic many vulnerable children from a village because arrests are generally focused on the place of exploitation and not on perpetrators complicit in other stages of trafficking.”

Young children are totally in the clutches of traffickers, Flavia Agnes, women’s rights lawyer and co-founder of Majlis, a non-profit that provides legal services to women and children, told IndiaSpend. “Delay in court is also a factor that has [an] adverse impact,” she said.

Rehabilitation often involves returning the child to the same parents who had initially trafficked them.

“We have to stop thinking that the natal family is a safe haven for young children and evolve innovative strategies of rehabilitation,” said Agnes. “The state has to take the onus to stop child trafficking in the country.”

Trafficking widespread across India

Three in five–or 9,034 of 15,379–persons trafficked in 2016 were children (below 18 years), NCRB data show. Of these, 4,911 (54%) were girls and 4,123 (46%) were boys.

West Bengal reported the most children trafficked, followed by Rajasthan (2,519), Uttar Pradesh (822) and Gujarat (485).

West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Odisha are common source areas for trafficking to red-light areas across India, according to the India Country Assessment Report 2013 on anti-human trafficking, brought out by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Sexual exploitation for prostitution (22%) was the second major purpose for human trafficking in 2016 in India, after forced labour (45%), NCRB data based on the statement of rescued victims and the accused showed.

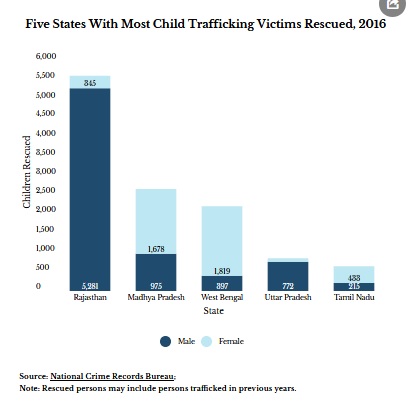

More than 23,000 victims were rescued in 2016, of which 61% or 14,183 were children and 39% adults. Of the 14,183 children, 61% were boys and 39% girls.

Rajasthan reported having rescued the most–5,626 or 40% of all victims below 18 years. Madhya Pradesh (2,653) was next, followed by West Bengal (2,216), Uttar Pradesh (852) and Tamil Nadu (648).

West Bengal rescued the most (1,819) female victims below 18 years, followed by Madhya Pradesh (1,678) and Tamil Nadu (433).

Gap in data and under-reporting

“Existing prevalence data–from secondary sources–for human trafficking for CSE do not exist as victims are a hidden population and there is no valid survey method to track it,” the World Vision report said. Estimates of women and girls in CSE vary from 70,000 to 3 million in India, it added.

NCRB data reveal only reported cases, Joseph Wesley, head of anti-child trafficking programme at World Vision India, told IndiaSpend. “From our experience, I can say that not all cases are reported, simply because parents are very hesitant to report or parents themselves are involved.”

“Police should be proactive in booking the cases under trafficking provisions,” he said. “Often cases are booked as kidnapping or missing person cases even though there is clear evidence of trafficking.”

Insufficient data hinder work for organisations such as World Vision India. Government agencies’ work also suffers–lack of data makes it difficult to detect and target high-prevalence areas, making it difficult to focus prevention and law enforcement efforts effectively, Wesley added.

“Lack of data makes it very difficult to track the gravity of the situation and the scanty numbers indicate that there is no immediate problem,” said Agnes. “Officials tend to dismiss or undermine the problem. Having accurate data on such a serious issue is critical to evolve effective strategies. Many NGOs are now in the process of compiling data about child trafficking. Though this is not official data, it is useful as a pointer.”

“There is a global data gap in reporting trafficking,” said Mendonca. “It is not easy for trafficking victims to report because many of them are from some of the most vulnerable and marginalised sections of society but a lot of data is lost due to lack of an integrated data collection system.”

“Integrated reporting and use of digital databases by police would result in more accurate national collation of data,” said Mendonca. “Once first information reports and chargesheets are entered into a digital system, there would be more accurate reports of trafficking crimes.”

(This article is a part of the World Vision India-LDV fellowship on child trafficking.)

Correction: The story was updated to correct the headline.

(Paliath is an analyst and Mallapur is a senior analyst at IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend

“The day he died we went to buy school dress, pencils and everything else for the other children. He was getting fever for some days. I took him to a local hospital [near Majhauli], they said that his blood count is low and asked me to take him somewhere else. In Dudhi too, the doctors expressed their inability to treat him and asked my son to be taken elsewhere. I then went home to get some money because I had no idea how much it will cost.

My son said, Ma ask didi to cook something, it won’t be nice to eat from anywhere else in the night. Then we went to the Hindalcohospital and they took him in. He was admitted for several hours before a doctor even examined him. They kept delaying his treatment. The doctor who would come for the night shift would say that the blood transfer would take place in the morning. The next morning, by 8 am, when the shift was about to change they didn’t do anything. They didn’t even give him any medicines. Then my son started feeling more uncomfortable, asking for our relatives from the village to be be called, they took time. He told me, either you are lying or there is some problem. I tried to assure him but his condition kept worsening,”

Sokalo Gond, Sonbhadra UP

Forest rights leader and human rights defender SokaloGond has made an appeal to align protests opposing the Supreme Court order on eviction and government’s anti-forest rights stand with that of the martyrdom of her 13 year old son who died in a Hindalco hospital in Sonbhadra, UP five years back, due to alleged careless and lack of care.

In 2013, MithileshGond, SokaloGond’s died in Hindalco hospital located in Renukoot, Uttar Pradesh (UP) because of the reported carelessness of the doctors there. Mithilesh was in desperate need of blood but even after twelve hours of being in the hospital and despite the urgency of the situation, the then CMO there, Dr.PramodYadav didn’t give blood to the 13 year old boy. An investigation into this matter led to the conclusion that there was indeed carelessness in the manner the case was dealt with. However, no action was taken against the callous doctors. This is a regular phenomenon in the hospital especially with the poor labourers and Adivasis in the nearby areas, who have no option but to knock at the doors of this hospital for the treatment. When a struggle was waged against this by the All India Union for Forest Working People (AIUFWP), the leading faces of the struggle were charged with false cases under serious charges.

Even today, the struggle for a decent healthcare so that young children like Mithilesh don’t meet the same fate is going on. The forest dwellers, mainly Adivasis and Dalits have to travel far and wide in order to avail even the most basic healthcare services. Even they make it to these public health centres (PHCs) or government hospitals, they are met with apathy and indifference. They are repeatedly fooled for money, as well. The struggle for a decent life of dignity with bare minimal healthcare facilities is real. Every year, Mithilesh’sShahadatDiwas(Martyrdom day) is celebrated on the 600 acres of Birsa Nagar land that was claimed under the community forest rights.

This year too, his Shahadatdiwas will be celebrated on the same land in Majhauli, Dudhi in UP’s Sonbhadra.

https://cjp.org.in/forest-rights-organisations-urge-goi-to-defend-fra-2006/

Join our mailing list to get the latest human rights news that matters, straight to your mailbox.

Join our mailing list to get the latest human rights news that matters, straight to your mailbox.

© Sabrang | All Rights Reserved