Nuh (Haryana), New Delhi, Mumbai: She may be the head of her village, but making rotis for her extended family of 22 is still her responsibility.

Farhuna (right) is the sarpanch of Hussainpur village in Haryana’s Nuh district. An arts graduate, Farhuna makes rotis on a chulha for her extended family of 22.

Hunched over the small chulha (earthen stove) in the family house at Hussainpur village in Haryana’s Nuh district, her hands efficiently slapping a small piece of dough into a round roti, Farhuna (she uses one name), smiled when she recalled the circumstances of her marriage–and election.

It was early in 2016. The panchayat elections were around the corner and the Haryana government had recently introduced a new eligibility condition. To contest the elections, women needed to prove that they had cleared their eighth standard exams; men had to be matriculates.

That year, the seat at Hussainpur was reserved for women. The problem: No woman in her husband’s family had ever been to school.

So Farhuna’s father-in-law began looking for a bride for his son. His only condition: Education. “He didn’t even take any dowry,” grinned Farhuna, proud holder of a bachelor of arts degree.

The family has a gas stove over which the vegetables and dal are made. But rotis taste better when they come out of a mud stove, and that is how they are made–some 70 of them for the afternoon and an equal number for the night meal–said Farhuna.

Between the roti-making and taking care of her six-month-old daughter, there isn’t much time for the sarpanch (village head) to attend panchayat meetings. Moreover, two sisters-in-law are to be married in a few weeks’ time, so the two-storey house is being painted and there is no time to step out of the house. So, said Farhuna, her father-in-law by and large attends to panchayat matters.

But when she can make the time, Farhuna attends meetings. “I’ve got roads made and I alone look at the problems with the government school in the village. That is my area of interest,” she said.

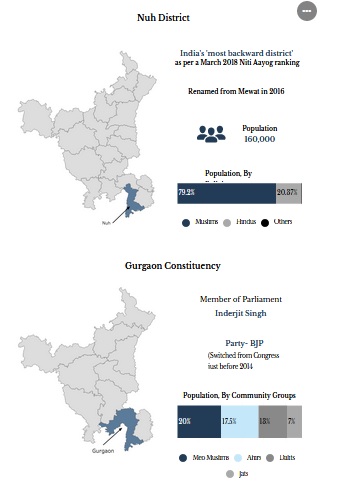

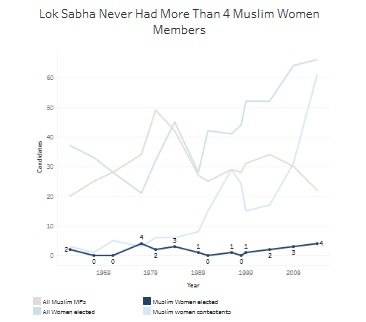

Low political representation is a problem at every level. Currently, only four of 543, or 0.7% members of the outgoing Lok Sabha are Muslim women, who comprise 6.9% of the general population.

Five Lok Sabhas since Independence had no Muslim women members

Five of the 16 Lok Sabhas since Independence have had no Muslim women members, and their number never crossed four in the 543-seat lower house of parliament.

India has 14 Muslim-majority Lok Sabha constituencies, according to this November 2018 report by Mayank Mishra in The Quint. In addition, there are 13 constituencies where Muslims comprise more than 40% of the population. There are a total of 101 seats where Muslims make up more than 20% of the population.

Muslims comprise 14.3% of the population, according to Census 2011, but only 22 of 543 members of parliament (MPs)–over 4%–in the outgoing Lok Sabha are Muslim.

Partly, this is because mainstream political parties are reluctant to filed Muslim candidates. In 2009, only 30 of 543 MPs (5.52%) were Muslim, according to an analysis by Christophe Jaffrelot, French scholar and columnist, published in Seminar, a monthly journal published out of New Delhi. That election saw only 832 Muslim candidates, of which nearly half or 47.12% contested as independents.

Things weren’t much better in 2014 when 320 of 3,245 candidates (9.8%) who contested the general election were Muslim. The BJP fielded just seven Muslim candidates out of 428 (or 2%), Jaffrelot wrote in the March 2019 book Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India. None won. The Congress fielded 27 Muslim candidates out of 462–less than 6% of the total and fewer than the 31 it had endorsed in 2009.

Amongst non-Muslim parties, only the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) fielded more than 15% Muslim candidates–at 18.4%, 20.7%, and 15%, respectively.

But Muslim women face a double bind–discriminated against both as women and as Muslims. “In terms of cumulative discrimination–being a Muslim and being a woman–there is a compounding effect for sure,” said Gilles Verniers, a political science professor at Ashoka University and co-director of the Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD). “The usual barriers to entry that apply to all women, apply even more strongly to Muslim women.”

Despite evidence of an increasing number of women candidates, five of the 16 Lok Sabhas since Independence, including the first one, have had no Muslim women MPs, and at its best, the figure has never crossed four.

Source: Lok Sabha, Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Indian Legislators Dataset

“The candidacy of Muslim women has been abysmal ever since Independence and over time, the problem has worsened,” said Zoya Hasan, retired professor emerita at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “The dominant party, the right-wing, is determined to exclude Muslims from political representation and puts up very few candidates. Amongst these, Muslim women are even fewer in number.”

Amongst the candidates announced so far, the BJP has fielded just one Muslim woman. Mafuja Khatoon is contesting from Jangipur, West Bengal and is the first-ever Muslim woman candidate fielded by the BJP for the Lok Sabha.

The outgoing Lok Sabha initially had only two women MPs: Mamtaz Sanghamita, a doctor and first-time MP of the All India Trinamool Congress (popularly abbreviated to TMC), and Mausam Noor of the Congress, a two-term MP from Maldaha. Two Muslim women became MPs only in 2018 in separate by-elections: Sajda Ahmed, from the TMC was elected in February 2018 while Tabassum Hasan, who had represented Kairana, Uttar Pradesh, as a Bahujan Samaj Party MP in 2009, won her second term in a May 2018 by-election from the seat on a Rashtriya Lok Dal ticket.

An early analysis by TCPD of candidates for the first phase of the 2019 general elections found 111 women amongst 1,279 candidates. Just two of these women are Muslim. In phase two, there were 156 women amongst 1,202 candidates analysed by TCPD. Of these, seven–two each from the TMC and the Congress, and one each from the RJD, BJP and SP–are Muslim.

‘They are banning triple talaq but killing our men. How does that make any sense?’

The question of representation becomes significant at a time when Muslim women’s issues, particularly on instant triple talaq, are seen as a red letter issue by political parties.

The Triple Talaq bill, which makes instant triple talaq a criminal offence with provisions for a three-year jail term and a fine, was passed by the Lok Sabha in December last year after debates: Prominent speakers for the bill included Ravi Shankar Prasad, Smriti Irani and Meenakshi Lekhi of the BJP, while Ranjeet Ranjan, Mallikarjun Kharge and Sushmita Dev from the Congress spoke opposing it. Conspicuous by its absence was the voice of the Muslim woman.

“I personally don’t know a single woman who was divorced through instant triple talaq,” said sarpanch Farhuna. “It does not happen in our village.”

Are Muslim women likely to vote for the BJP because of its stand on triple talaq? “By banning triple talaq, the government has done a good thing,” said Farhuna. “But instant triple talaq is anyway not permitted in Islam and the government should not interfere in our religion.”

Women will vote according to their marzi, or choice, she added, but issues like mob lynching are likely to weigh on their minds.

The grave of Pehlu Khan in Jaisinghpur village in Haryana’s Nuh district. In April 2017, Khan was beaten to death on the suspicion that he was smuggling cows. Issues like mob lynching are likely to weigh on the minds of Muslim women voters, Farhuna says.

In Nuh itself, the murders in cow-related violence of Pehlu Khan, Rakbar Khan and Umar Khan hang like a pall of gloom. In Uned village, Jameela, who said she is 75 or 80 years old and is completely illiterate, tends to the family’s buffaloes. “We are dairy farmers but are scared to buy cows. We cannot even buy buffaloes from outside our own area,” she said. “Anyone can stop you on the way back.”

Will the ban on triple talaq by the Supreme Court in August 2017 work in the BJP’s favour? Seated on her string charpoy, Jameela looked down and said, “They are banning triple talaq but killing our men. How does that make any sense? How can we vote for them when our community is under threat from them?”

Jameela (right), who says she is 75 or 80 years old, tends to her family’s buffaloes. “We are dairy farmers but are scared to buy cows. We cannot even buy buffaloes from outside our own area,” she says. “Anyone can stop you on the way back.”

Voters don’t take electoral decisions on the basis of simple binaries, said Gilles Verniers. “Even if some Muslim women might have an improved opinion of the BJP, it does not erase everything else of the last couple of years.” Moreover, an attempt by the BJP to present instant triple talaq, a marginal social practice, as a widespread malaise that applies to Muslims as a whole could also create resentment, he said.

“All talk of gender justice for Muslim women is offset by mob lynching and hate crime,” said Mohd Arif, a journalist and social worker in the area. “Triple talaq will have no impact in Nuh.”

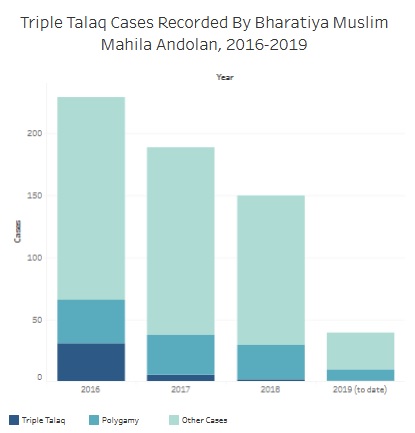

The Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA) office in Mumbai’s Bandra East keeps track of the number of instant triple talaq cases that come its way. The numbers plunged since 2017 onward when the Supreme Court declared the practice illegal.

Source: Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, Mumbai

“Those who claim to speak for us, have no idea about the rights given to women by Islam,” said Zubaida Khatoon, a woman qazi (priest) trained by BMMA to officiate at marriages.

Zubaida Khatoon, a woman qazi, was trained by the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan to officiate at marriages. “Those who claim to speak for us, have no idea about the rights given to women by Islam,” says Khatoon.

“Triple talaq was not the only issue we were fighting,” said BMMA founder Noorjehan Safia Niaz. “In our application to the Supreme Court, we had asked for a ban on not just triple talaq, but also polygamy and halala (a practice under which a divorced wife who wishes to remarry her former husband must first consummate an intervening marriage). Unfortunately, the court only heard us on triple talaq and not the other two issues.”

Yet, conceded Niaz, the ban has had a chilling effect on those who sought instant talaq, and the numbers have plummeted in recent years. “At least the [Narendra] Modi government brought in a law that has brought the practice down. But men can still bring in a second wife and Muslim women live in constant fear of this.”

What is needed is a comprehensive law that covers all three–instant triple talaq, polygamy and halala, she said. But a uniform civil code (UCC), a promise of the BJP in its manifesto, is not a solution. “A UCC is applicable to the whole country. First you need to ask 80% of Hindus if they want it,” Niaz said.

The BMMA has been at the forefront for social and legal reform guaranteed to Muslim women under both their religion and the Constitution. What it wants is for parliament to pass a comprehensive Muslim family law on the lines of the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955. This, said Niaz, would enable Muslim women to live a life of empowerment and dignity.

“It’s a pity that in 72 years of Independence, no government has given any thought to needed reforms,” said Niaz. “It’s convenient for everyone to just leave this issue alone. But why should Muslim women continue to live in fear? Are we not entitled to constitutional rights?”

Last month, the BMMA released a charter of demands ahead of the 2019 election. It wants political parties to adhere to supporting constitutional nationalism rather than any divisive ideology in the name of nationalism. It wants action against hate speech and religious polarisation and a halt to “open hatred by many right-wing groups and individuals in the last four-five years”. And it wants a “healing touch” and reassurance to minorities and Dalits “about their being equal citizens in a secular democracy”.

Nowhere in the seven-point charter is there any mention of the term ‘triple talaq’.

‘Peace. That is all we need.’

In the narrow lanes of Delhi’s Jamia Nagar, a small group of women is talking about what it is like to live in fear. Ever since Junaid was stabbed to death on a Delhi-Mathura train in June 2017, Sareena Begum who has studied till the fifth standard and has four children–three boys and a girl–said she cannot sleep till her children return home safe.

“If you have a beard, wear a kurta-pyjama and look a certain way, then you are a target out on the street,” said Sareena. “My husband has asked me to avoid wearing a burqa when I leave this locality. He doesn’t want me to stand out.”

Zubaira (she uses one name), a Delhi University graduate in political science who works as an assistant with a private company in Rohini, talked about what she expected from this election. “Peace. That is all we need,” she said.

Ayesha (she uses one name), who lives in Ghaziabad in a village dominated by Jat neighbours, said even a few years ago, she never felt insecure. But now, even though nobody has actually said anything to her, she feels apprehensive when she leaves her house. “It’s the way people look at you. We could be the next target,” she said. Growing up, she said, her family kept a cow for milk. They had Hindu friends. “I’m not saying the Congress is great. But at least there was no hate then.”

Wives of electricians and embroiderers, like voters everywhere, the women have a lot on their mind–from notebandi, the colloquial term for demonetisation, to unemployment. In the past, they said, they voted for whichever candidate they felt would be good for the area. “Arvind Kejriwal did a lot of work for us and improved schools and set up dispensaries. He got many of the roads here repaired and even the electricity bill came down,” said Ayesha. “He left a good job to come into politics.”

Now there is a new anxiety, fuelled by a combination of social media, nationalism, incidents of violence and the projection of candidates by the BJP such as Pragya Thakur, charged in a terrorist conspiracy case under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act.

“It’s not just one thing, it’s a combination of things,” said Dolly Siddiqui, a social worker active at Jamia Nagar. “Lynching incidents have not stopped and there is a continuing question on our desh bhakti (patriotism). Every day we are told to ‘go to Pakistan’.”

Social media has ripped the mask off civility maintained by neighbours. Zubaira talked of her husband’s childhood friend, a Hindu. The two grew up together, celebrating each other’s festivals. Now, the friend forwards hateful and often fake messages questioning the nationalism of Muslims. “My husband has not confronted him, but he has unfollowed him on Facebook,” she said.

For this group of women, it seems like a fight for survival. “Once you cross the metro line, you are away from this mohalla (area) and it is not safe for us over there,” said Sareena. “Our only aim is to defeat the BJP.”

(Namita Bhandare is a Delhi-based journalist who writes frequently on gender issues confronting India.)

Courtesy: India Spend.