Taken without context, the term ‘autonomy’ is generally associated with positive, progressive, even empowering connotations — with meanings ranging from freedom to self-government.

Courtesy: Newsclick.in

Courtesy: Newsclick.in

#JNULongMarchProtest, was manhandled by both women and men constables of the Delhi police. My phone was snached away by a woman police constable, glasses broken and lost. I tried explaining to them…showed them my press card. They said ‘phone wapas nahi milega…bhaar mein jao!’

Only when I threatened to write about it, they threw my phone back at me. They smirked and retorted saying ‘Action lengey. Dekhtey hain kitna press se ho tum’

Extremely angry and infuriated with the Delhi Police. What a sad and disgusting show of power! #shame

Journalist Aishwarya Adhikari‘s Facebook Post

The Delhi Police on Friday first cordoned off, and then ordered a lathi charge on thousands of JNU students and teachers, who were marching towards Parliament protesting against removal of several department heads and a coordinator for not complying with the university’s new attendance rules. The other demand included immediate suspension and arrest of Prof Atul Johri who is accused of sexual harassment. Many of the students have been detained. Several were seriously injured.

In a continuing attack on India’s premier central university — that began with the Modi government’s slapping sedition charges against students in February 2016, the Delhi police which is under the Ministry of Home Affairs simply did not allow the peaceful protest to take place. The 2-kilometre long march was quietly proceeeding from North gate of the campus to Parliaent street when they were suddenly stopped after Bhikaji Cama Palace before the Safdarjung Flyover. Suddenly the protesters were cordoned off and water canons were used before the lathi charge was resorted to. Following the brutality of the police, protesters went to INA and the Sanjay Park.

The Delhi Police on Friday ordered a lathi charge here on thousands of JNU students and teachers, who were marching towards Parliament protesting against removal of several department heads and a coordinator for not complying with the university’s new attendance rules. The other demand included immediate suspension and arrest of Prof Atul Johri who is accused of sexual harassment. Many of the students have been detained.

The long march was completely peaceful and orderly, with students walking in lines, shouting slogans, carrying placards. The police followed the procession in large numbers but the strength increased to over 200 at INA market where the road had been barricaded. Even before the students could react the cops moved in and started pushing them around. This angered the students who tried to move on.

This was all that the police had been waiting for and they attacked the students with lathis, and water canons. Police brutality is visible in the video below, posted on Twitter:

Not just JNU, but civil society and students from the other Delhi universities joined the march with thousands participating.Water canons were used against all in the march, including teachers and others who participated. The canons were taken down the length of the procession, to ensure that all were hit by the water.

The students are staging a peaceful and silent iprotest at INA, demanding release of the detained students. The march was in response to the open call by the JNU Students Union and Teachers Association to protest against the removal of deans and chairpersons from the Centres ; and the ongoing sexual harassment case where the accused Professor was arrested and released immediately on bail. The girls who have been harassed by him held a press conference in Delhi recently, and made it clear to the media that Johri was a serial offender. They also said that unlike the propaganda by some of his supporters in the BJP, they were not from the Left students organisations but actually most of them were registered members of the ABVP.

The JNU teachers are protesting against the removal of several department heads and a coordinator for not complying with the university’s new attendance rules, and a number of them are on a hunger strike.

Also, Nine women students have filed police complaints against Atul Johri, Professor at the School of Life Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), accusing him of sexual harassment, abuse of power and sexual misconduct.

The association said the university’s administration has not reached out to the faculty members who have been on the hunger strike for the past three days. It has also demanded that the management withdraw its notification removing the department heads and other circulars issued without consulting relevant university authorities.

The association also criticised the JNU administration over what it called selective inaction by the university against a professor accused of sexual harassment.

Meanwhile various representatives from the political parties rushed to the spot and extended support the students. Manoj Jha from RJD, Ali Anwar from JD(U) and Brinda Karat from the CPI(M) addressed the gathering.

Related Stories:

JNU students and teachers march to Parliament demanding reforms

More attacks on JNU: Seven Chairpersons, Deans removed over mandatory attendance

‘Serial Harasser’ professor being safeguarded by JNU Admin?

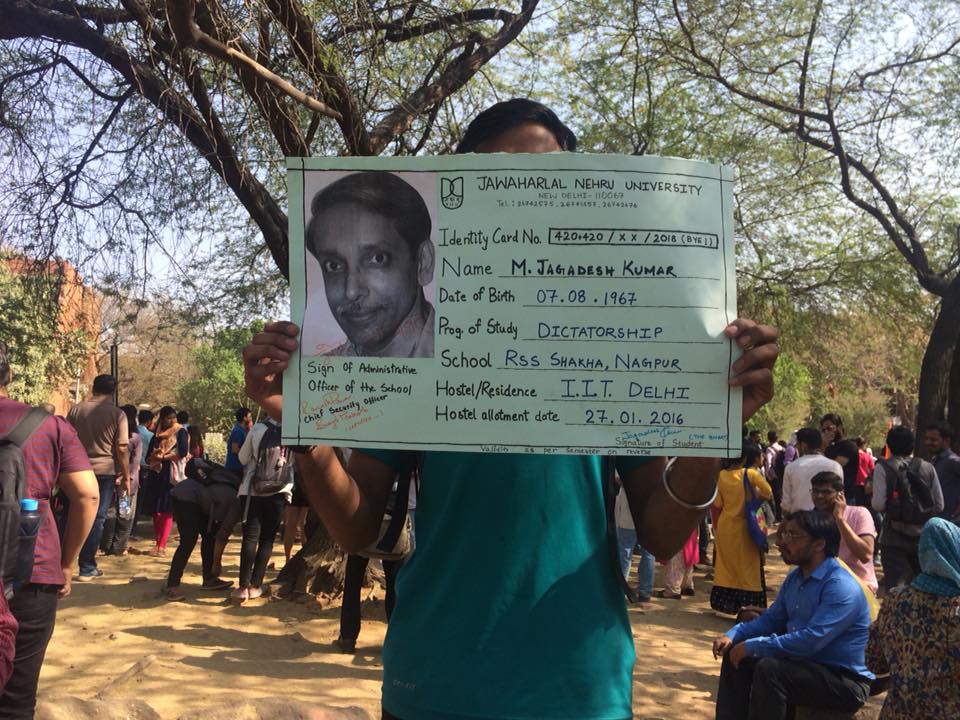

Students and teachers from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) marched from the JNU campus to Parliament in Delhi on Friday, in a move that the JNU Students Union (JNUSU) and JNU Teachers Association (JNUTA) labelled the ‘Long March’. The teachers have spoken out against the institution’s current vice-chancellor, Professor M. Jagadesh Kumar, whom they accuse of trying to “wreck and ruin” JNU “with the help of the media and the political establishment”. The teachers said that “the VC has presided over a massive seat cut in JNU, depriving our ordinary poor and hardworking students of the opportunity to come and study at an institution like JNU.”

They allege that in his two year tenure JNU has known no peace, effective implementation of reservation policy has been violated, safety of women students has been compromised, students and faculty members have been harassed and tormented. “And worst of all, there has been a physical disappearance of one student from the campus in broad daylight and about whom we have not heard for the last year and a half, leading many to the painful conclusion that he may no longer be alive,” they said explaining the reason behind the march.

Dissatisfaction with the university’s management has been brewing at JNU ever since the student protest of February 2016 when dissenting students were targeted by the state with alleged complicity of right leaning members of the University administration. The disappearance of Najeeb after an altercation with ABVP goons as well as a series of unpopular administrative decisions that appeared to target disadvantaged or dissenting students, lead to growing discontent among not just students but also teachers. The immediate trigger though, appears to be the lax manner in which Prof Atul Johri, who had been accused of sexual harassment and intimidation by atleast 9 young female students of JNU, had been let off with little more than a slap on the wrist. This is especially troubling in light of GS CASH being scrapped leaving female students vulnerable.

The JNUTA has several demands, including the rescinding of notifications replacing chairpersons who were against mandatory attendance. The teachers’ organisation is also seeking the rescinding of an executive council decision on the establishment of a committee to take action against individual teachers, according to JNUTA president Sonajharia Minz. The JNUTA had earlier organised a three-day ‘satyagraha’ movement on the institution’s campus to vocalise these demands. The move to grant autonomy to the university is also being perceived as privatisation in disguise and therefore against the interests of students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

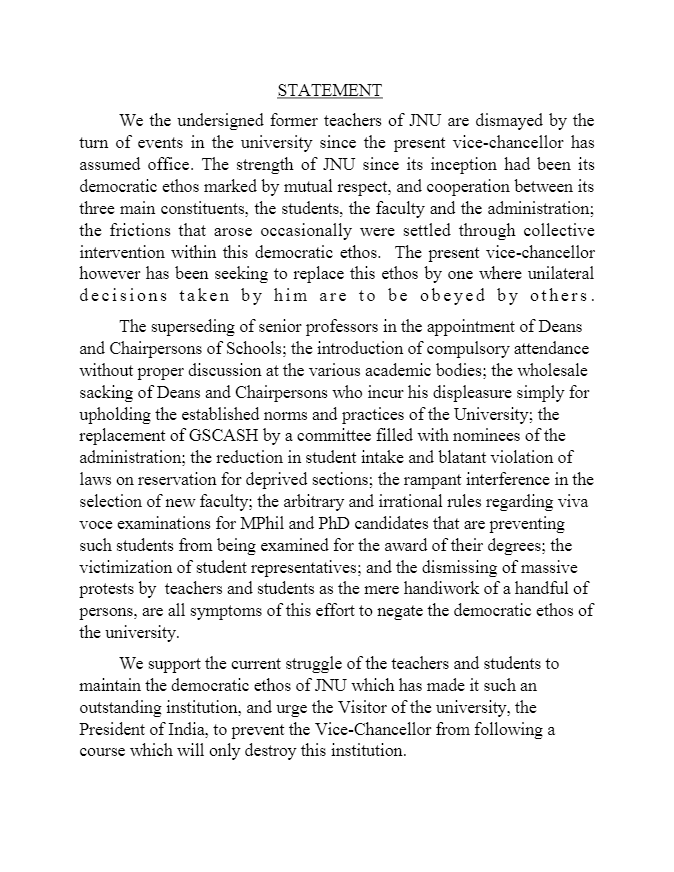

18 former members of JNU’s faculty have also released a letter in support of “the current struggle of the teachers and students to maintain the democratic ethos of JNU which has made it an outstanding institution.” The letter outlines the signatories’ regarding issues at JNU, including “the reduction in student intake and blatant violation of laws on reservation for deprived sections; the rampant interference in the selection of new faculty;” as well as “the victimization of student representatives; and the dismissing of massive protests by teachers and students as the mere handiwork of a handful of persons”. It may be read in full here. Signatories to the letter also include historian Romila Thapar, Sunanda Sen, Harbhans Mukhia, Prabhat Patnaik and Zoya Hasan among others.

The University Grants Commission (UGC) on March 20, 2018 announced that it will grant full autonomy to 62 institutes of higher education, including five central and 21 state universities. It is being said that institutes getting autonomous will be free to decide their admission procedure, fee structure and curricula. The Human Resource Development Minister, Prakash Javadekar said that universities with a rating over 3.6 from the National Assessment and Accreditation Council will be granted autonomy. He tweeted that this is “in line with the vision of PM Narendra Modi towards liberalised regulatory regime.”

Central universities that will be granted autonomy are Jawaharlal Nehru University, Aligarh Muslim University, Banaras Hindu University, the University of Hyderabad and the English and Foreign Languages University. Apart from that, state universities like Jadavpur University, Andhra University, Algappa University etc. will also be granted autonomy.

Responding to this announcement, the Academics for Action and Development (AAD) said in a press release today, “The announcement by the Minister of HRD granting of autonomy to 62 universities and colleges, which includes five central universities also, represents the government’s unilateral policy for privatisation of existing public-funded institutions. AAD strongly opposes the announcement made by the Minister, which will deprive the SC, ST, OBC and poor students from these universities and colleges and contractualisation of the teachers therein.”

The full press release can be read below:

ACADEMICS FOR ACTION & DEVELOPMENT (AAD)

*Press Release*

The announcement by the Minister of HRD granting of autonomy to 62 universities and colleges, which includes five central universities also, represents the government’s unilateral policy for privatisation of existing public-funded institutions. AAD strongly opposes the announcement made by the Minister, which will deprive the SC, ST, OBC and poor students from these universities and colleges and contractualisation of the teachers therein.

In the garb of this autonomy and freedom to open new departments/courses in self-financing mode, the present courses run by the universities and the colleges are going to be decimated. The freedom is infact a trap for self-destruction. The UGC regulations under which this autonomy has been granted, provides:

1. All universities and colleges are to be graded in categories I/II/III.

2. The institutions with NAAC score of more than 3.5 or NIRF ranking upto first 50 are marked in Category I.

3. The institutions with NAAC score between 3.25 and 3.5 or NIRF ranking between 51 to 100 are to be in Category II.

4. The remaining institutions are to be in Category III.

5. The central universities under category I are to get Autonomy without any expert committee visit. Such institutions can run their own departments/syllabi but in a self-financing mode.

6. The board of management will decide the variable salary and service conditions of individuals.

7. The board of management will be free to appoint foreign faculty upto 20℅ at negotiable lucrative salary and admit foreign students upto 20%.

8. In the name of autonomy the existing institutions will be transformed into teaching shops running market-friendly courses through their off campus branches and distance education outlets.

9. The so-called autonomous institutions will have market oriented fee structure with the amount soaring up to lakhs as documented in these regulations, where the non-returnable processing fees is Rs. 10000 if a student withdraws after having taken admission.

What is most unfortunate is that no discussion was held with the stakeholders, the teachers, non-teaching staff and students who will be adversely affected by the government’s brazen agenda of privatisation of the higher education. Such a serious decision was taken without any discussion with the teacher associations of these universities and FEDCUTA.

AAD strongly opposes this decision of the MHRD-UGC and appeals to the MHRD to take this draconian decision back as it would lead to the exploitation of teachers, non-teaching staff and students.

Press Secretary

Richa Raj/SBN Tiwary/Chittaranjan Kumar/Ashok/Rajesh Jha

Following recent observations on the “misuse” of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act by the bench of judges U.U. Lalit and A.L. Goyal, which laid down stringent safeguards before victims could register a case under the SC/ST (POA) Act, Former Secretary to the Government of India, P.S. Krishnan, who also held many important positions including key member of the National Commission for SCs/STs, has appealed to the Union Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment Thaawar Chand Gehlot that the government should “urgently move the Supreme Court, requesting that a larger Bench of the Court revisit the above judgment, rescind the directions and expunge certain observations therein.”

On March 20, 2018 the bench allowed anticipatory bail for an accused (of POA) Act, also drastic conditions such as requiring a DySP to conduct a “preliminary enquiry” to rule out “frivolous and motivated” complaints, and mandating prior sanction of an appointing officer or SSP before arresting a public servant or other citizens. These conditions are likely to pose further challenges to victims of caste based atrocities.

Krishan requested the Government to present a holistic picture such as the socio-historical background of the Act, the extreme vulnerability of the SCs and STs and the importance of not diluting any of the provisions of the Act. He suggested that any delay in taking action on this will also impact several other areas where SC/STs are already facing challenges, such as the question of GOI-PMS scholarships. It will be setting a bad precedent in that sense.

He also suggested that the Atrocities Act must be included in the Ninth Schedule so as to protect it from judicial view. He mentions that the Government of India should become a Party in all State appeals pending in the Supreme Court against High Court acquittals in cases like Tsunduru of Andhra Pradesh and Laxmanpur Bathe and Batahni Tola massacres.

He advised the Government to immediately issue a statement which could make it “clear that it shares the distress of the SCs and STs on the judgment, expressing its intent to quickly move the Supreme Court as above and clarifying that it does not agree with the reported gratuitous admission and misinterpretation of the ASG in the court, and assuring that the protection of the SCs and STs is a paramount goal of the Government. This will assuage the feelings of SCs and STs and remove suspicions which have found public expression that the Government, through weak pleadings in the case before the Supreme Court, colluded in bringing about the present situation.”

The key arguments on which he based his requests were attached in the form of an annexure, which we have summarised below:

Brief History of enactment of SC/ST (POA) Act

The SC-ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act was enacted in 1989 under the leadership of the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, in view of the large scale atrocities that plagued vulnerable communities in India. The next government headed by V.P. Singh had operationalised the Act. A further amendment was made recently in 2015.

The letter argues that there has been a consensus across party line on the need for the strengthening of the Act. The letter noted that rural India is plagued with large scale discrimination against the SCs as there are clear divisions in villages depending on land ownership and most land is owned by dominant castes, leading to an almost complete alienation of Dalits in the areas. This is further strengthened by the wide-spread prevalence of “Untouchability’ which is still practiced despite the Constitutional bar in Article 17 and the PCR Act.

Because of these clear cut biases and hostility of the state machinery, which in itself constituted people from dominant castes, the letter noted that it was difficult to secure proper investigations and quick and successful trials. The letter drew attention to caste based massacres in which conviction could not be secured. It presented the case of Kizhavenmani atrocity, Laxmanpur Bathe, Kambalapalli, Karnataka.

Supreme Court observations on a Caste-less society

The letter quoted the observations and vision of the Supreme Court for a caste free society, it highlighted, “There cannot be any difference about the observation of the Supreme Court that a caste-less society must be created. But to give the impression that the Act is perpetuating casteism is not correct and needs expunging. Casteism can be abolished only if its underpinnings are eliminated, such as the landlessness of SCs, the misappropriation of the lands of STs, lack of irrigation for SC and ST lands, unavailability of quality education from the pre-school to the highest level for SCs and STs, their high neo-natal, infant, under-five and child mortality rates, stunting, anaemia etc. in all of which they fare the worst among all social groups, and so on. These have to be tackled. Mere slogans and verbal attacks on the caste system will not eliminate it.”

It argued that the POA Act 1989 and the POA Amendment Act 2015 are part of a package of comprehensive measures which caters to all spheres of life-economic, occupational, education etc.

Government case for upliftment of SC/STs requires strengthening

It also argued that the Government’s case can only be strengthened if it is able to show that it is genuinely concerned about the welfare of SC/STs through measures like legislation for Special Component Plan for SCs ad Tribal sub-plan (TsP) and SC and ST Development authorities, national campaigns in all states for grant of lands to all rural SC families and landless ST families with pattas/ownership documents and peaceful possession and other measures.

A case for Representation

It requested the courts to evolve a system whereby such judgments in matters pertaining to vulnerable classes and categories do not come from any of the Bench of the Supreme Court to which people look up for supreme justice. It also suggested that special efforts should be made that qualified individuals belonging to the SCs and STs and other disadvantaged sections and also women are consciously brought to the Bench of the Supreme Court so that adequate representation is provided to them

Escaping Arrests detrimental to principles of Justice

Making a very strong argument against the provision of anticipatory bail to the accused, the letter noted, “Government may point out that as perpetrators or promoters of atrocities are powerful individuals belonging to the dominant community of the village or area and the victims belong to the two most vulnerable classes, arrest of the accused has significant psychological value in the area. If such persons escape even arrest through anticipatory bail, it will be perceived as indication of the ability of such persons not to be even touched by the long-arm of the law. It is on account of this reality that in the original Act 1989 itself anticipatory bail has been precluded. The dilution of Section 18 of the Act by conditionalities such as those directed in the judgment of 20.3.2018 will encourage powerful perpetrators and potential perpetrators of atrocities, will encourage such police and other officers who suffer from widespread caste-bias, and demoralize and scare the already weak and vulnerable SCs and STs.

Finally, it urged the government to dissociate itself from the ASG Shri Maninder Singh’;s statements before the Court as reported in Times of India March 21 report.

And the most important observation it made was that the observation of the Bench that “abuse” of law is happening, is a very drastic observation not supported by evidence and facts. It drew attention to the fact that whenever SCs have tried to stake a claim on lands, they have faced atrocities. In fact large scale atrocities take place on Dalits because of this particular issue. Apart from that SC/St women are routinely harassed, and their resistance also routinely becoming a cause for further injustices.

The full text of the letter may be accessed here

Related Articles

— Attacks on Dalits 2nd Highest in Gujarat: DNA

— Dalits Attacked On Daily Basis, But Government Remains Apathetic

Image: Theresa May and Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, March 2018. PA Images/Victoria Jones, all rights reserved.

A former Research Fellow at Chatham House and the ex-Director of the World Development Movement, British historian Mark Curtis has published several books on UK foreign policy, including 2003’s Web of Deceit: Britain’s Real Role in the World, endorsed by Noam Chomsky and John Pilger. Ian Sinclair asked Curtis about the recently published new edition of his 2010 book Secret Affairs: Britain’s Collusion with Radical Islam.

Ian Sinclair: With the so-called ‘war on terror’ the dominant framework for understanding Western foreign policy since 9/11, the central argument of your book – that Britain has been colluding with radical Islam for decades – will be a shock to many people. Can you give some examples?

Mark Curtis: UK governments – Conservative and Labour – have been colluding for decades with two sets of Islamist actors which have strong connections with each other.

In the first group are the major state sponsors of Islamist terrorism, the two most important of which are key British allies with whom London has long-standing strategic partnerships – Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The second group includes extremist private movements and organisations whom Britain has worked alongside and sometimes trained and financed, in order to promote specific foreign policy objectives. The roots of this lie in divide and rule policies under colonialism but collusion of this type took off in Afghanistan in the 1980s, when Britain, along with the US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, covertly supported the resistance to defeat the Soviet occupation of the country. After the jihad in Afghanistan, Britain had private dealings of one kind or another with militants in various organisations, including Pakistan’s Harkat ul-Ansar, the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), all of which had strong links to Bin Laden’s al-Qaida. Covert actions have been undertaken with these and other forces in Central Asia, North Africa and Eastern Europe.

For example, in the 1999 Kosovo war, Britain secretly trained militants in the KLA who were working closely with al-Qaida fighters. One KLA unit was led by the brother of Ayman al-Zawahiri, then Bin Laden’s right-hand man. The British provided military training for the KLA at secret camps in Kosovo and Albania where jihadist fighters also had their military centre. The ‘dirty secret’ of the July 2005 London bombings is that the bombers had links with violent Islamist groups such as the Harkat ul-Mujahidin whose militants were previously covertly supported by Britain in Afghanistan. These militant groups were long sponsored by the Pakistani military and intelligence services, in turn long armed and trained by Britain. If we go back further – to the 1953 MI6/CIA coup to overthrow Musaddiq in Iran – this involved plotting with Shia Islamists, the predecessors of Ayatollah Khomeini. Ayatollah Seyyed Kashani – who in 1945 founded the Fadayan-e-Islam (Devotees of Islam), a militant fundamentalist organization – was funded by Britain and the US to organise opposition and arrange public demonstrations against Musaddiq.

More recently, in its military interventions and covert operations in Syria and Libya since 2011, Britain and its supported forces have been working alongside, and often in effective collaboration with, a variety of extremist and jihadist groups, including al-Qaida’s affiliate in Syria. Indeed, the vicious Islamic State group and ideology that has recently emerged partly owes its origins and rise to the policies of Britain and its allies in the region.

Although Britain has forged special relationships with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, it has not been in strategic alliance with radical Islam as such. Beyond these two states, Britain’s policy has been to collaborate with Islamist extremists as a matter of ad hoc opportunism, though it should be said that this has been rather regular. Whitehall does not work with these forces because it agrees with them but because they are useful at specific moments: in this sense, the collaboration highlights British weakness to find other on-the-ground foot soldiers to impose its policies. Islamist groups appear to have collaborated with Britain for the same reasons of expediency and because they share the same hatred of popular nationalism and secularism as the British elite.

IS: Why has the UK colluded with radical Islamic organisations and nations?

MC: I argue that the evidence shows that radical Islamic forces have been seen as useful to Whitehall in five specific ways: as a global counter-force to the ideologies of secular nationalism and Soviet communism, in the cases of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan; as ‘conservative muscle’ within countries to undermine secular nationalists and bolster pro-Western regimes; as ‘shock troops’ to destabilise or overthrow governments; as proxy military forces to fight wars; and as ‘political tools’ to leverage change from governments.

This collusion has also helped promote two big geo-strategic foreign policy objectives. The first is influence and control over key energy resources, always recognised in the British planning documents as the number one priority in the Middle East. British operations to support or side with Islamist forces have generally aimed at maintaining in power or installing governments that will promote Western-friendly oil policies. The second objective has been maintaining Britain’s place within a pro-Western global financial order. The Saudis have invested billions of dollars in the US and British economies and banking systems and Britain and the US have similarly large investments and trade with Saudi Arabia; it is these that are being protected by the strategic alliance with Riyadh.

IS: You include a chapter in the new edition of the book exploring the UK and West’s role in Syria. Simon Tisdall recently noted in The Observer that the West has been “hovering passively on the sidelines in Syria”. This is a common view – including on the Left. For example, in September 2014 Richard Seymour asserted “The US has not been heavily involved” in Syria, while in February 2017 Salvage magazine published a piece by Dr Jamie Allinson, who argued it was a myth that “the US has pursued a policy of regime change” in Syria. What is your take on the West’s involvement in Syria?

MC: These are extraordinary comments revealing how poorly the mainstream media serves the public. I’ve tried to document in the updated version of Secret Affairs a chronology of Britain’s covert operations in Syria to overthrow the Assad regime. These began with the deployment of MI6 and other British covert forces in 2011, within a few months after demonstrations in Syria began challenging the regime, to which the Syrian regime responded with brute force and terrible violence. British covert action, mainly undertaken in alliance with the US and Saudi Arabia, has involved working alongside radical and jihadist groups, in effect supporting and empowering them. These extremist groups, which cultivated Muslim volunteers from numerous countries to fight Assad, have been strengthened by an influx of a massive quantity of arms and military training from the coalition of forces of which Britain has been a key part. At the same time, Britain and its allies’ policy has prolonged the war, exacerbating devastating human suffering.

UK support for Syrian rebel groups long focused on the Free Syrian Army (FSA), described by British officials as ‘moderates’. Yet for the first three years of the war, the FSA was in effect an ally of, and collaborator with, Islamic State and al-Qaida’s affiliate in Syria, al-Nusra. London and Washington continued to provide training and help send arms into Syria despite the certainty that some would end up in the hands of jihadists. Some of the militants who joined the Syrian insurgency with British covert support were Libyans who are believed to have been trained by British, French or US forces in Libya to overthrow Qadafi in 2011. Some went on to join Islamic State and also al-Nusra, which soon became one of the most powerful opposition groups to Assad.

Britain appears to have played a key role in encouraging the creation of the Islamic Front coalition in Syria in November 2013, which included groups which regularly worked with al-Nusra; these included Liwa al-Tawhid – a group armed by Qatar and which coordinated attacks with al-Nusra – and Ahrar al-Sham – a hardline Islamist group that rejected the FSA. Both groups contained foreign jihadists, including individuals from Britain. Ahrar al-Sham’s co-founder, Abu Khalid al-Suri, was linked to the 2004 Madrid bombing through a series of money transfers and personal contacts; a Spanish court document named him as Bin Laden’s ‘courier’ in Europe. The same network was connected to the 2005 London terror attack.

The UK role in Syria has not been minor but has been an integral part of the massive US/Arab arms and training operations, and British officials have been present in the control rooms for these operations in Jordan and Turkey. Britain also consistently took the lead in calling for further arms deliveries to the rebel forces. British covert action was in the early years of the war overwhelmingly focused on overthrowing Assad: evidence suggests that only in May 2015 did UK covert training focus on countering Islamic State in Syria.

IS: What role has the mainstream media played with regards to Britain working with radical Islam?

MC: It has largely buried it. In the period immediately after the 7/7 bombings in 2005, and more recently in the context of the wars in Libya and Syria, there were sporadic reports in the mainstream media which revealed links between the British security services and Islamist militants living in Britain. Some of these individuals have been reported as working as British agents or informers while being involved in terrorism overseas and some have been reported as being protected by the British security services while being wanted by foreign governments. This is an important but only a small part of the much bigger picture of collusion which mainly concerns Britain’s foreign policy: this is rarely noticed in the mainstream.

IS: The British public and the anti-war movement are not mentioned in your book, though they seem a potentially important influence on the nefarious and dangerous British foreign policies you highlight?

MC: Yes, it’s largely down to us, the British public, to prevent terrible policies being undertaken in our name. We should generally regard the British elite as it regards the public – as a threat to its interests. The biggest immediate single problem we face, in my view, is mainstream media reporting. While large sections of the public are deluged with misreporting, disinformation or simply the absence of coverage of key policies, there may never be a critical mass of people prepared to take action in their own interests to bring about a wholly different foreign policy.

The mainstream media and propaganda system has been tremendously successful in the UK – the public can surely have very little knowledge of the actual nature of British foreign policy (past or present) and many people, apparently, seriously believe that the country generally (although it may make some mistakes) stands for peace, democracy and human rights all over the world. When you look at what they read (and don’t read) in the ‘news’ papers, it’s no surprise. The latest smears against Corbyn are further evidence of this, which I believe amounts to a ‘system’, since it is so widespread and rooted in the same interests of defending elite power and privilege.

The other, very much linked, problem, relates to the lack of real democracy in the UK and the narrow elitist decision-making in foreign policy. Governments retain enormous power to conduct covert operations (and policies generally) outside of public or parliamentary scrutiny. Parliamentary committees, meant to scrutinise the state, rarely do so properly and almost invariably fail to even question government on its most controversial policies. Parliamentary answers are often misleading and designed to keep the public in the dark. Past historical records of government decision-making are regularly withheld from the public, if not destroyed to cover up crimes. British ‘democracy’, which exists in some forms, otherwise resembles more an authoritarian state.

There are fundamental issues here about how policy gets made and in whose name. It’s not an issue of whether Labour or Conservative is in power since both obviously defend and propagate the elitist system. Jeremy Corbyn himself represents a real break with this but the most likely outcome, tragically, is that the Labour extremists (called ‘moderates’ in the mainstream) and the rest of the conservative/liberal system which believes in militarism, neo-liberalism and the defence of privilege, will prevail if and when Corbyn becomes Prime Minister.

The signs are already there in the Labour manifesto for the last election, which would have continued the present extremism in most aspects of UK foreign policy, even if it promised some change and still represented a major challenge to the establishment. Again, it will obviously be up to us to change policies, democratize the media and transform British governance more broadly.

Ian Sinclair is the author of The March That Shook Blair: An Oral History of 15 February 2003, published by Peace News Press. He tweets @IanJSinclair.

Courtesy: https://www.opendemocracy.net/

Women presenting their demands to the elected ward of their district. UHRC

Shabnam Verma, Neeraj Verma, Kanupriya Kothiwal, Shrey Goel helped on the study and are team members and volunteers of Urban Health Resource Centre

According to the latest census, there are about 13.7 million slum households in all of India, of which 4.9 million are neither recognised nor notified. Considered as informal, such settlements are often deemed illegal by authorities, especially when newly formed. This supposed “illegality” presents challenges to the residents, adding housing instability and fear of displacement to their struggle of finding livelihood while trying to settle down in a new city.

At the same time, several government policies such as the National Urban Health Mission mandate the inclusion of listed and unlisted slums as well as vulnerable populations for services pertaining to living environment such as water supply, sewage, electricity and streets, all of which impact health.

The Indian government does not formally designate any human habitation as “illegal” in policies. However, officials and elected municipal representatives often consider slums de facto “illegal”. At the same time, slum dwellers being recognised as voters with a basti (slum) address on voter cards shows that the illegality can be overcome.

Service provision can be quite slow for many segments of the population and often exclude weaker and vulnerable sections of the society. Consequently, continuous proactive efforts are necessary to “pull” services from the government so that they reach the vulnerable habitations.

The north-eastern peri-urban part of the city of Indore has attracted a population of poor migrants from Rewa and Khargaon districts in Madhya Pradesh and from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (northern Indian states). Initially about 20 to 30 families moved and developed a settlement in 2014. Previously consisting of a fairly small strip of land and a brick kiln, it served as a site for open defecation and garbage dump for residents of other slums in the vicinity.

It was only when the land was purchased by a real estate broker, who cleared and levelled the site, that this until then unnamed-area started gaining the attention of migrants. The newly emerging settlement presented the possibility of lower-cost housing relative to other slums in Indore and the opportunity to earn livelihood working in nearby factories, construction sites and market places.

Unpaved pathway. UHRC

Migrants started settling in the area amid unpaved paths, with no electricity or running water. Unpaved streets hampered the movement of residents to and from the settlement and were a hazard for children playing outside. The lack of electricity and water forced residents to travel long distances to fetch water, and left them with no fans in Indore’s 40° or 45° Celsius peak heat-waves and no lights in the dark.

How would the new residents face up to these challenges? Often, civic authorities dismiss their demands by saying “there is no scheme presently” and “there are no orders right now”.

Women of the emerging settlement learned about the activities of our organisation, the Urban Health Resource Centre (UHRC), which mentored and trained women’s groups with 12 to 15 members in neighbouring slums to help them access various services.

UHRC social workers visited the new settlement and listened to the challenges of the residents. Through regular meetings and participatory discussions, two groups were formed: Sakhi Saheli Mahila Samooh (Friends and Sisters Women’s Group) and Nai Kiran Mahila Samooh (New Light Women’s Group) in the end of 2014.

In early 2015 members of these newly formed women’s groups discussed with more established groups in the neighbouring bastis as to what actions they had undertaken to obtain municipal services. They learned that gentle, perseverant negotiation was the best way forward.

Women meeting social workers to discuss strategies. UHRC, Author provided

Through UHRC’s training and with the help of women from other, more established groups, residents of the new area acquired knowledge and skills about writing petitions in the local language, Hindi, and submitting them to the ward councillor, the municipal corporation and at the district public hearing. At the top of the list were improvements such as paving streets and running water. When the ward councillor rejected their application, saying their basti was “illegal”, the women asserted their rights as citizens and highlighted the value of their votes in elections.

The women’s repeated efforts resulted in the construction of bore-well in one of the areas of neighbourhood and the paving of road in the slum lanes. As of October 2016, 30% of the pathway had been paved. The efforts for the construction of another bore-well and the paving of the remaining pathway are ongoing.

Women showing their joy as the streets are getting paved. UHRC, Author provided

A petition was submitted in December 2016 followed by several in-person representations to the ward councillor in the next six months and several written reminders. In November 2017, when the ward councillor visited the neighbourhood, the residents gently urged him to have the bore-wells installed. As a temporary measure, the community informally accessed water by paying families of the adjacent older slums (who had their private bore-wells) at a monthly rate of INR 100 per family.

The mentoring role of previously established groups is analogous to the emergence of informal solidarity networks in Greece when the government introduced austerity measures owing to an economic collapse beginning 2009-10.

Writing petitions together. UHRC

These informal solidarity networks played a crucial role in helping people overcome difficulties caused by austerity measures and economic instability. The support and guidance of more established community groups helped UHRC learn that the presence of stronger groups has a “ripple” effect on neighbouring settlements. We also learned that soft skills such as tact and a no confrontational approach toward authorities, negotiations through community requests sustained over a long period of time can bring services to informal settlements and help overcome the notion of “illegality” held by officials.

The strategies in place eventually successfully “pulled” services from the municipal corporation and benefited a population of 1,575.

Created in 2007, the Axa Research Fund supports more than 500 projects around the world conducted by researchers from 51 countries. To learn more about the work of Dr. Siddharth Agarwal, visit the dedicated site about The AXA Outlook Award action research entitled “Knowledge and Action Bridge towards Community Risk Assessment and Resilience Building” which is implementing actionable solutions to overcome slum level challenges by foregrounding community wisdom.

Siddharth Agarwal, Director, Urban Health Resource Centre

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Nachangulam Panchayat, Sivagangai district (Tamil Nadu): What is it like to do a full-time job without a salary? Especially if you are a dalit or an adivasi woman and your daily earnings sustain your family?

Rajanikandham, the dalit president of Nachangulam panchayat in Tamil Nadu’s Sivagangai district, has no assets. The state pays her an honorarium of Rs 1,000 a month, and she often ends up paying out of her pocket to visit the district collectorate for panchayat work. Having no fixed income affects dalit and adivasi women presidents disproportionately since they have to do a full-time constitutional role at the expense of their wages and employment.

Ask Rajanikandham, a dalit daily wage worker, who heads the Nachangulam village panchayat in southern Tamil Nadu’s Sivagangai district. Her husband too earns daily wages and the couple have three children, one of whom is disabled.

A state-run, guaranteed rural job scheme like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is critical for poor families like these but as a panchayat head, Rajanikandham is not allowed to profit from it.

“I hold an office, I have power and prestige but no income. I get no salary from the panchayat and I can’t work for wages under MGNREGA because I am panchayat president,” she said. “All I have are three goats I got under a government scheme.”

In Tamil Nadu, panchayat presidents–an elected full-time constitutional role–are not paid any salaries. The only other states in India that do not pay a salary to its rural elected representatives are Maharashtra, Gujarat and Odisha.

Panchayat presidents in Tamil Nadu are paid an honorarium of Rs 1,000 to cover travel expenses and an additional Rs 100 for attending a meeting twice a month.

Compare this to the earnings of a member of the state’s legislative assembly (MLA)–after a recent 100% hike, he/she receives a basic monthly salary of Rs 1.05 lakh, apart from the several perks and pensions. The last time Tamil Nadu revised its honorarium for panchayat officials was in 2012, when it was hiked from Rs 300 to Rs 1,000. And the meeting fee was raised from Rs 50 to Rs 100.

This Rs 1,000 is barely enough to cover the panchayat head’s expenses for the mandatory weekly meeting at the block development office (BDO) or the regular trips to the district collectorate to lobby for extra funds for development projects and procure information about different government schemes.

In the first part of our series, we saw how Tamil Nadu’s women panchayat leaders were changing the face of rural governance. In the second part today, we investigate the financial challenge they face every day, especially dalit and adivasi women leaders: How to raise money for poorly funded development projects even as they struggle with poverty at home.

This is a problem male panchayat leaders face too but the honorarium system puts even greater pressure on women from marginalised communities. Like many working women, they also have to deal with social and familial pressures as they struggle to bring in extra resources for the panchayat. Unlike men, they cannot spend long hours away from home, lobbying for funds with the male-dominated network of higher officials.

“For women, taking a day out and travelling to the district collectorate periodically and spending an entire day there is difficult,” said Rajeswari, of Kuruthangudi panchayat (Kalaiyarkovil block) in Sivagangai district, who belongs to the Parayar community. “They have to answer so many questions from their families and society. We are often asked, ‘What is the need to go out so often and come back late?’”

Women leaders also have to deal with insults and slander for being out of their homes and travelling. “Earlier, posters of women (leaders) would be put up in villages calling them ‘characterless’ for staying out late for panchayat work. Things got a bit better after the state government gave strict orders to district collectors to ensure that only women attended meetings and not their male relatives,” said G Uma, assistant professor in the gender department at Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), who has researched on women in Tamil Nadu’s panchayat governance.

Yet, when women had to choose between a regular salaried job and the power to make a change, IndiaSpend found many opting for the latter.

Tenmozhi, the president of Sitilinghi panchayat in the reserved forests of Tamil Nadu’s Dharmapuri district, gave up a job offer from the state’s electricity board to fulfil her constitutional role as an elected representative. When women had to choose between a regular salaried job and the power to make a change, IndiaSpend found many women panchayat presidents opting for the latter.

Tenmozhi, a maths graduate from the tribal Malayali community who featured in our series last year, declined a job offer from the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board because she was just elected the president of her panchayat and wanted to set the agenda for change.

50% of dalit women panchayat heads are daily wage workers

The state bars panchayat presidents from holding a paid employment or any job that receives government funding, such as employment under MGNREGA, to avoid conflict of interest.

But consider what this means to women whose families survive on daily earnings. In our survey of 32 panchayats headed by women in six districts of Tamil Nadu, we found that dalit and adivasi women came with almost no assets and meagre family incomes.

Six of the 12 dalit women we interviewed were daily wage workers with no assets at all. The other six were slightly better off, owned between 1-5 acres of lands. Two of the three adivasi women lived in a one-room tenement, and subsisted on either daily wage work or collecting forest produce. In contrast, women from the dominant castes such as Thevars, Gounders and Vanniyars had family ownership of lands ranging from 10 acres to 30 acres.

For those who worked in private jobs, there were other kinds of problems. Dalit women panchayat leaders from the Arunthatiyar community, who mostly earned their living from daily wage work on farms owned by dominant castes like Thevars and Gounders, had a particularly difficult time managing with meagre resources.

Taking time off their daily wage work to travel on official business to various district and block offices means loss of the day’s wages, which is not compensated in any form by the panchayat.

To add to all this, a panchayat leader is expected to serve refreshments for visiting government officials. Often, they are also expected to refuel the vehicles of the visiting government staff.

“A visiting engineer who prepares plans and estimates for civil works or a visiting deputy BDO (block development officer) often demands that the president pay for their fuel. These lower level bureaucrats have fuel limits set by the government,” said IGNOU researcher Uma.

IndiaSpend saw these problems first hand when we visited a panchayat where a block-level official insisted that the president arrange refreshments despite our protests. She ended up spending Rs 300 out of her pocket.

In Dindigul district, George Dimitrov, a lecturer in Gandhigram Rural University, who has researched and documented all the 25 dalit women presidents, found that 11 women from the Arunthatiyar community worked as daily wagers in the farms of dominant caste landholders. A lack of salary affects their autonomy and makes it difficult for them to resist the demands of their employers.

Saroja heads the Kakkadasam panchayat in Krishnagiri district but it is her husband who actually controls it. For her, MGNREGA is more than just work. “I wanted for this term to end soon so I can go for MGNREGA work. I feel like a slave in this household,” Saroja said. “MGNREGA work gives me the freedom and a community of women I can talk to. This job has snatched away my freedom without giving me any real power.”

Tamil Nadu’s neighbouring state, Kerala, pays its panchayat leaders Rs 13,200, the highest in the country. Telangana has recently revised the salary to Rs 5,000 while Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have revised it to Rs 3,000.

| Income Of Panchayat Presidents In Some Indian States | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Salary | Honorarium |

| Goa | 4000 | |

| Maharashtra | 1000 | |

| Gujarat | 500 | |

| Jharkhand | 1000 | |

| Bihar | 2500 | |

| West Bengal: | 3000 | |

| Odisha | 1000 | |

| AP | 3000 | |

| Telangana | 5000 | |

| Karnataka | 3000 | |

| Kerala | 13200 | |

| Tamil Nadu | 1000 | |

| Haryana: | 3000 | |

| HP | 3000 | |

| Punjab | 1200 | |

| Uttar Pradesh | 3500 | |

Source: Data collected from state panchayat raj department websites

Mobilising resources: How women manage despite odds

As we reported in the first part of this series, women leaders were going beyond their assigned duties–such as provision of drinking water, sanitation, streetlights, road repair–to invest in services which have been neglected by their male predecessors.

But mobilising extra funds is difficult because of how Tamil Nadu’s panchayat finance is structured. The panchayat has three revenue sources:

Own revenues, over which panchayats have complete control, constitute only 10% of the total revenues, as per our analysis. These are mainly from the taxes that panchayats can levy on their residents–house tax, profession tax, water tax, advertisement tax and some licenses and fees.

In a micro study of three villages in Tamil Nadu, Anand Sahasranaman of Institute of Financial Management Research (IFMR) Trust estimated that this own revenue is usually sub-optimal: It makes for only 0.15% to 0.2% of the total village income.

Rates of house tax–the largest source of own revenues–have not been revised in many years and are kept flat irrespective of the size of properties. Poor households actually end up subsidising rich ones. If panchayats were to increase their tax collection to even 2.5% of village incomes, their own revenues would increase by 15 times, calculated Sahasranaman’s study.

The state government has also abolished matching grants to the house tax collected, an incentive for better tax collection.

Panchayats, thus, have to depend on devolved grants and pooled assigned revenues, which form two-thirds of the total revenues.

Based on the fourth State Finance Commission (SFC) (2012-2016) recommendations, the state government designated 10% of the state tax revenues as grants to urban and rural local bodies in the ratio of 42:58. Gram panchayats are assigned 60%, the highest among the three tiers of rural governance.

But even while the state government increased the SFC grants, ‘untied funds’ that can be used freely, from 8% in 1997 to 10% in 2012, it imposed a more complex system of bureaucratic approvals on them. For instance, 10% of the SFC grants due to panchayats are now reserved for Infrastructure Gap Filling Fund, which is under direct control of the district collector.

Every panchayat in Tamil Nadu gets a uniform SFC grant of Rs 3 lakh (revised down from Rs 5 lakh after enhanced revenues from the 14th Central Finance Commission in 2015) and an added grant based on the population. A panchayat of 2,000 population gets anywhere between Rs 5 lakh and Rs 8 lakh annually from the devolved SFC grants.

This finance architecture, while being the same for all panchayats, affects those headed by women more.

Large development projects require massive capital outlays, which materialise after lobbying for a number of years. Tenmozhi, as we reported in our earlier series, had to lobby with the Centre for two years for a Rs 30-crore grant to build a bridge connecting 5,000 people from seven villages.

‘I had to struggle for everything’

Lobbying demands time, effort and access to officials of the district collectorate. Women have a tougher time investing in these.

Rajeswari of Kuruthangudi panchayat is popular in her district for her skills in mobilising funds for various schemes. But for a Parayar dalit, it did not come easy. She recounted her story:

“I had to struggle for everything–ration shop, school, library. We have no funds to build these. Most of the big scheme funds as well as NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) funds are handled by the assistant director of panchayats. We need to regularly show our face to get funds. Men go directly to him, sit with him for a long time and ensure funding. We can’t.”

Rajeswari has been able to manage the time and expenses for travel because of a supportive family and a husband who holds a government job. But this is not the story of other dalit and adivasi women presidents.

Mazharkodi Dhanasekar (left) of Melamarungoor panchayat is from a dominant caste, and her family owns 15 acres of land. She spent Rs 1 lakh of her own money to build toilets under Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. Leaders such as Prema (centre) and Rajeswari (right), dalit presidents of Kurthangudi and Silakkapatti panchayats, have to lobby hard for funds. This takes time, effort and access to officials–easier for their male counterparts.

Even self-employed women like Prema, the president of Silakkapatti panchayat in Sivagangai district who runs a small general store in her village, has a tough time because shutting shop means loss of business.

Other important sources of funding like MLA and MP funds and funds from district and block panchayat unions (additional tiers of local governance) need political access to male-dominated networks. This, women leaders said, is hard work especially for first-timers. Although panchayat leaders are not supposed to be affiliated to political parties, such affiliations are now common and, often, determine funding.

Manjula, who heads Mallachandaram panchayat (Thally block in Krishnangiri district), managed to get public works worth Rs 26 crore sanctioned. This included a brand new high school building, several roads, and a ration shop. It is not lost on her that this was possible her husband is a member of the district unit of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK).

“MLAs as well as district and block chairpersons prioritise party loyalists. Here, if you are from the AIADMK, there is greater chance of getting more funds,” she said. “Also MLAs allocate certain amount for each block so they can fund only a few panchayats. So we have to be seen constantly when they are in their constituency to get attention.”

Manjula, the president of Mallachandaram panchayat in Tamil Nadu’s Krishnagiri district, managed to get public works worth Rs 26 crore sanctioned. It is not lost on her that this was possible her husband is a member of the district unit of All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. Leaders who are party loyalists have better chances of getting funds allocated from members of legislative assembly and parliament.

Mazharkodi Dhanasekar, the feisty president of Melamarungoor in Sivagangai district whose campaign against open defecation we featured in our last series, had to spend Rs 1 lakh of her own money to build toilets under the Swachh Bharat Scheme. As a member of the dominant Maravar community, a subcaste of the Thevars, whose family owns 15 acres of land, it was easier for her.

“I could do it because we are financially well off and my husband did not object,” she said. “Many women neither have the money nor the independence. We need more funds to build necessary infrastructure.”

Women leaders are bullied by upper-caste employers

Since 2006, panchayats in Tamil Nadu have seen greater bureaucratisation, with increased government control and shrinking autonomy. Autonomy over funds that are necessary for routine maintenance works, such as repair of streetlights, have been tightened. Lower-level block officials are now assigned to exercise greater control over the panchayats.

“Earlier, the BDO was only advising the presidents. Now the deputy BDO has greater control,” said Kalpana Satish, who has trained women panchayat presidents and worked with the Federation of Women Panchayat Presidents. “Panchayat presidents cannot sign cheques without their permission. Even for untied funds, presidents have to make a proposal and send to the BDO and wait for his approval.”

As per Tamil Nadu Panchayat rules, presidents can spend upto Rs 600 for repairs to hand pumps and Rs 7,500 for motor pump maintenance without an approval from engineers. Presidents are allowed upto Rs 2,000 at a time or Rs 5,000 a year for urgent public works without any technical approval. This is grossly inadequate, said women leaders.

“Everyday there is some problem with pipelines, motors and their maintenance. Is Rs 2,000 enough?” asked Thulasimani (30), the dalit president of Koombur panchayat in Dindigul.

Thulasimani has often been the target of casteist attacks from the upper-caste Gounder men because she dared to sit on the president’s chair.

Thulasimani, the dalit president of Koombur in Tamil Nadu’s Dindigul district, has often been the target of casteist attacks from the upper-caste Gounder men. Presidents are allowed upto Rs 2,000 at a time for urgent public works without any technical approval. Since 2006, panchayats in Tamil Nadu have seen greater bureaucratisation, with increased government control and shrinking autonomy. Lower-level block officials are now assigned to exercise greater control over the panchayats.

“When we get calls from people, especially upper castes, to repair a motor pump, we don’t have the time to wait for estimates and approvals. We have to repair then and there,” she said. “Sometimes we get credit, but many times we even have had to borrow at an interest from moneylenders.”

Despite all these structural challenges, women are delivering beyond the basic services and this is not because of the system, but in spite of it. Tamil Nadu’s finance system for local governance is a classic example of how systems are designed without envisioning the roadblocks they present to the most marginalised groups.

This is the second of a five-part series on women panchayat leaders in Tamil Nadu. You can read the first part here.

(Rao is a co-creator of GenderandPolitics, a project which tracks women’s representation and political participation in India at all levels of governance.)

Courtesy: India Spend

Join our mailing list to get the latest human rights news that matters, straight to your mailbox.

Join our mailing list to get the latest human rights news that matters, straight to your mailbox.

© Sabrang | All Rights Reserved