How can visualising hate crimes in south Asia enhance understanding and serve as a basis for organising policy and public action?

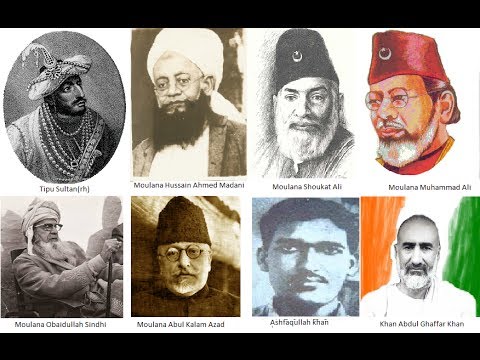

Image credit: Information Guru

Like many places in the world, South Asia has seen a rise in violence and injustice against people who are minorities in terms of religion, ethnicity and gender, as well as political activists, academics and journalists. Provoked by state and non-state actors, these instances erode the space of dissent, free thought and human rights, pointing to a wider culture of rising intolerance and hate.Yet these incidents appear and disappear daily in our media-saturated imaginations.

Watching them play out in each national context, often in quick succession, leaves little time to absorb and make sense of them. Looking beyond the immediacy of mainstream and social media, how can we think about the relationships between incidents of hate and intolerance, understand overarching patterns and structures, or start to question their terrifying frequency? Spurred by an ambition to understand this landscape of intolerance, we turned to mapping it.

Tracking intolerance

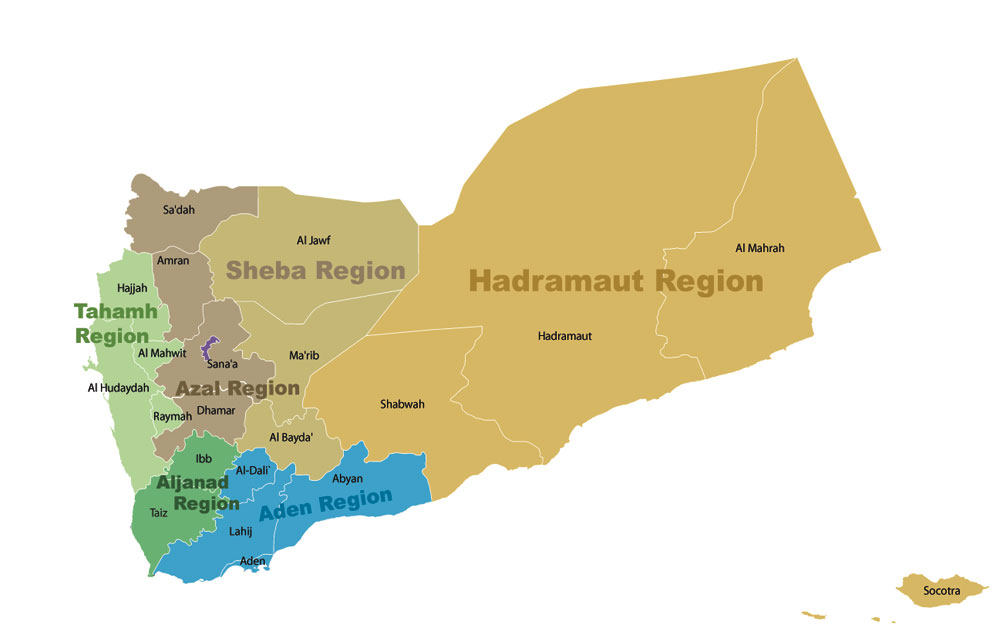

About a year ago we launched a site called "Intolerance Tracker", in collaboration with Timescape, a map-based storytelling platform, to document cases of violence and hate across South Asia — in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Aggregating ongoing and recent incidents across national borders seemed to be one way of trying to draw connections between different types of hate crimes, local conditions, types of perpetrators and so on.

We categorised incidents according to victims, perpetrators, and the cleavages that motivate or ground these cases, such as gender, religion, caste, ethnicity, ideology, and sexual orientation. At the time of writing, the tracker has aggregated close to 400 incidents.

Maps can serve as powerful devices for constructing, unpacking or understanding different narratives. A system of stories presented on a map allows us to observe and understand the spatial, temporal, and social relationships that exist within that place.

Internet-based, real-time mapping provides a powerful tool to build awareness and engagement during social or political conflicts, as well as natural disasters and epidemics. Public contributions – from earthquakes or flood zones, and even refugee camps or conflict zones – can spur fuller comprehension of how dynamic situations evolve and inform responses to crises.

Local initiatives

In our own project we took inspiration from a number of other initiatives. Some are focused on a particular cause or phenomenon, such as "I Paid a Bribe", where members of the public can report cases of retail corruption in India, providing an insight into the relationship between the individual and the state, and the compulsions that encourage corrupt practices.

Similarly, “FemMap", another crowd mapping platform, highlights projects related to women and gender equality all around the world. In this approach, a camaraderie and community is built among people working across different social and regional contexts driven by similar motivations and ambitions.

The Environmental Justice Atlas uses mapping to document social conflict around environmental issues, foregrounding the struggles of local communities. The EJAtlas acts as a shared platform and database allowing environmental justice activists and other groups working on ecological and social issues to build paths towards corporate and state accountability.

In the United States, where violent hate crimes and incidents of intolerance have seen an alarming rise, the South Poverty Law Center’s Hate Map provides a powerful visual understanding of the geographies of fascist, racist, ultra-nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-LGBT groups, as a basis for organizing policy and public action.

Seeing together

Visual aggregation through maps allows stories that might be spatially and temporally distant to be seen together. It then becomes possible to identify underlying structures, trends and patterns that illustrate similarities and contrasts. South Asia’s shared history means that despite national borders, incidents between countries often share similar characteristics, and even forms of violence can find chilling echoes across borders (‘honour’ killings in India and Pakistan are one such example).

The existing data on the map already reveals some interesting and alarming trends. In more than a third of the cases, government actors (including the police) are themselves perpetrators of hate and intolerance and this is seen across all the countries where incidents are mapped.

Government actors (including the police) are themselves perpetrators of hate and intolerance.

People targeted on the basis of activism and ideology, a category that covers protesters, journalists, and those expressing dissent, also account for more than a third of the incidents mapped. Perhaps unsurprisingly, while the basis for government intolerance spans many categories (such as ideology, gender, ethnicity or religion), two-thirds of these are against actors who dissent or protest, often against the state itself. The alarming trend of the state’s role in stifling dissent points to the structural rather than incidental nature of this culture of intolerance.

Another category that is widely represented, accounting for more than one-fourth of all incidents reported on the map is that of religious intolerance, spread evenly across the subcontinent. As a visual medium, the ‘intolerance tracker’ allows us to make connections and identify dissonance between different categories in more engaging ways. This makes the platform a potential tool for research, to educate and generate awareness about intolerance. Finally, as it is supported by verifiable data which is well organised, it can also be a useful tool for advocacy, especially as its database grows.

Uneven geographies

Yet, maps and data visualizations come with their own baggage. Rather than conveying neutral truths or blunt facts about space and society, they are projections containing biases, aspirations and assumptions. As media scholars argue, the sources and means of gathering data, as well as the visual or algorithmic conventions used to visualize and present information, need to be critically approached.

In our case, being limited (for the time being) to reports from verifiable media outlets, we are keenly aware that the map represents not just a landscape of intolerance, but also a media landscape. The intolerance map is skewed towards a view that reinforces the mainstream attention towards certain issues, perhaps at the expense of others, and given the politicised and polarised nature of the problem, the map might reproduce some of these uneven geographies of information.

Our own implicit biases in collecting and posting stories are also no doubt embedded in its visualisation. Moving forward, we will continue to acknowledge these discrepancies, and hopefully move beyond some of them through partnerships with researchers, journalists, community organisations and NGOS, allowing for a more diverse range of sources and thus a thicker reading of the landscapes of intolerance.

In his seminal essay, “The Agency of Mapping”, James Corner discusses the ways in which we may engage maps not as neutral objects – representing some kind of truth about space – but as cultural agents actively participating in making and remaking the environment. Rather than a comprehensive or static account of reality or a domain of ‘experts’ – as cartographic endeavours often tend to be – we are interested in exploring a collaborative and grassroots ethic of mapping that can help foster social change, engender new communities and encourage interdisciplinary research.

We invite you to help us build the ‘intolerance tracker’ as a mode of inquiry into a changing and difficult phenomenon: a living archive as well as an instrument to meant to spark insights, debates and provocations.

(This story was first published on openDemocracy).